Bruce Lee

| Bruce Lee | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

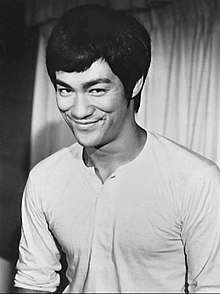

Lee in the film The Big Boss | |||||||||||||

| Background information | |||||||||||||

| Chinese name | 李小龍 (traditional) | ||||||||||||

| Chinese name | 李小龙 (simplified) | ||||||||||||

| Pinyin | Lǐ Xiǎolóng (Mandarin) | ||||||||||||

| Jyutping | Lei5 Siu2 Lung4 (Cantonese) | ||||||||||||

| Born |

Lee Jun-fan 李振藩 (Traditional) 李振藩 (Simplified) Lǐ Zhènfān (Mandarin) Lei Zan Faan (Cantonese) November 27, 1940 Chinatown, San Francisco, California, U.S. | ||||||||||||

| Died |

July 20, 1973 (aged 32) Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong | ||||||||||||

| Resting place | Lake View Cemetery, Seattle, U.S. | ||||||||||||

| Residence | Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong[1] | ||||||||||||

| Origin | Kowloon, Hong Kong[2] | ||||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Washington | ||||||||||||

| Occupation |

| ||||||||||||

| Years active | 1941–1973 | ||||||||||||

| Nationality |

Hong Kong[3] United States | ||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | |||||||||||||

| Children |

Brandon Lee (1965–1993) Shannon Lee (born 1969) | ||||||||||||

| Parents |

Lee Hoi-chuen (1901–1965) Grace Ho (1907–1996) | ||||||||||||

| Siblings | Robert Lee (born 1948) | ||||||||||||

| Ancestry | Jun'an, Shunde, Guangdong, China | ||||||||||||

| Website |

Bruce Lee Foundation Bruce Lee official website | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Lee Jun-fan (Chinese: 李振藩; November 27, 1940 – July 20, 1973), known professionally as Bruce Lee (Chinese: 李小龍), was a Hong Kong and American actor, film director, martial artist, martial arts instructor, philosopher,[6] and founder of the martial art Jeet Kune Do, one of the wushu or kungfu styles. Lee was the son of Cantonese opera star Lee Hoi-chuen. He is widely considered by commentators, critics, media, and other martial artists to be one of the most influential martial artists of all time[7] and a pop culture icon of the 20th century.[8][9] He is often credited with helping to change the way Asians were presented in American films.[10]

Lee was born in Chinatown, San Francisco, on November 27, 1940, to parents from Hong Kong, and was raised with his family in Kowloon, Hong Kong. He was introduced to the film industry by his father and appeared in several films as a child actor. Lee moved to the United States at the age of 18 to receive his higher education at the University of Washington in Seattle,[11] and it was during this time that he began teaching martial arts. His Hong Kong and Hollywood-produced films elevated the traditional Hong Kong martial arts film to a new level of popularity and acclaim, sparking a surge of interest in Chinese martial arts in the West in the 1970s. The direction and tone of his films dramatically changed and influenced martial arts and martial arts films in the US, Hong Kong, and the rest of the world.[12]

He is noted for his roles in five feature-length films: Lo Wei's The Big Boss (1971) and Fist of Fury (1972); Golden Harvest's Way of the Dragon (1972), directed and written by Lee; Golden Harvest and Warner Brothers' Enter the Dragon (1973) and The Game of Death (1978), both directed by Robert Clouse.[13] Lee became an iconic figure known throughout the world, particularly among the Chinese, based upon his portrayal of Chinese nationalism in his films.[14] He trained in the art of Wing Chun and later combined his other influences from various sources into the spirit of his personal martial arts philosophy, which he dubbed Jeet Kune Do (The Way of the Intercepting Fist). Lee held dual nationality in Hong Kong and the US.[15] He died in Kowloon Tong on July 20, 1973, at the age of 32.[16]

Early life

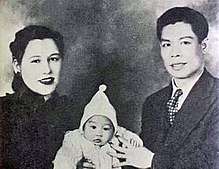

Bruce Lee was born on November 27, 1940, at the Chinese Hospital, in San Francisco's Chinatown. According to the Chinese zodiac, Lee was born in both the hour and the year of the Dragon, which according to tradition is a strong and fortuitous omen.[17] Lee and his parents returned to Hong Kong when he was three months old.[18]

Bruce's father, Lee Hoi-chuen was Han Chinese, and his mother, Grace Ho (何愛瑜), was of Eurasian ancestry.[19] Grace Ho was the adopted daughter of Ho Kom-tong (Ho Gumtong, 何甘棠) and the half-niece of Sir Robert Ho-tung, both notable Hong Kong businessmen and philanthropists.[20] Bruce was the fourth of five children: Phoebe Lee (李秋源), Agnes Lee (李秋鳳), Peter Lee (李忠琛), and Robert Lee (李振輝).

Grace's parentage remains unclear. Linda Lee, in her 1989 biography The Bruce Lee Story, suggests that Grace had a German father and was a Catholic.[21] Bruce Thomas, in his influential 1994 biography Bruce Lee: Fighting Spirit, suggests that Grace had a Chinese mother and a German father.[22] Lee's relative Eric Peter Ho, in his 2010 book Tracing My Children’s Lineage, suggests that Grace was born in Shanghai to a Eurasian woman named Cheung King-sin.[22] Eric Peter Ho said that Grace Lee was the daughter of a mixed race Shanghainese woman and her father was Ho Kom Tong. Grace Lee said her mother was English and her father was Chinese.[23] Fredda Dudley Balling said Grace Lee was 3/4s Chinese and 1/4th British.[24]

However, in his 2018 biography, Bruce Lee; A Life, Matthew Polly identifies Bruce's Lee's mother's grandfather as Moses Hartog Bosman. Born to a Jewish family in Rotterdam, Bosman became a successful businessman in Hong Kong, where he had a Chinese concubine named Sze Tai with whom he had six children, including Lee's grandfather Ho Kom Tong. Bosman subsequently abandoned his family and immigrated to California.[25] Ho Kom Tong, however, became a wealthy businessman with a wife, 13 concubines, and 30 children, one of whom was °Grace Ho, Lee's mother.[26][27]

Names

Lee's Cantonese birth name was Lee Jun-fan (李振藩).[28] The name homophonically means "return again", and was given to Lee by his mother, who felt he would return to the United States once he came of age.[29] Because of his mother's superstitious nature, she had originally named him Sai-fon (細鳳), which is a feminine name meaning "small phoenix".[30] The English name "Bruce" is thought to have been given by the hospital attending physician, Dr. Mary Glover.[31]

Lee had three other Chinese names: Lee Yuen-cham (李源鑫), a family/clan name; Lee Yuen-kam (李元鑒), which he used as a student name while he was attending La Salle College, and his Chinese screen name Lee Siu-lung (李小龍; Siu-lung means "little dragon"). Lee's given name Jun-fan was originally written in Chinese as 震藩, however, the Jun (震) Chinese character was identical to part of his grandfather's name, Lee Jun-biu (李震彪). Hence, the Chinese character for Jun in Lee's name was changed to the homonym 振 instead, to avoid naming taboo in Chinese tradition.

Family

Lee's father, Lee Hoi-chuen, was one of the leading Cantonese opera and film actors at the time and was embarking on a year-long opera tour with his family on the eve of the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong. Lee Hoi-chuen had been touring the United States for many years and performing in numerous Chinese communities there.

Although many of his peers decided to stay in the US, Lee Hoi-chuen returned to Hong Kong after Bruce's birth. Within months, Hong Kong was invaded and the Lees lived for three years and eight months under Japanese occupation. After the war ended, Lee Hoi-chuen resumed his acting career and became a more popular actor during Hong Kong's rebuilding years.

Lee's mother, Grace Ho, was from one of the wealthiest and most powerful clans in Hong Kong, the Ho-tungs. She was the half-niece of Sir Robert Ho-tung,[20][32] the Eurasian patriarch of the clan. As such, the young Bruce Lee grew up in an affluent and privileged environment. Despite the advantage of his family's status, the neighborhood in which Lee grew up became overcrowded, dangerous, and full of gang rivalries due to an influx of refugees fleeing communist China for Hong Kong, at that time a British Crown colony.[30]

After Lee was involved in several street fights, his parents decided that he needed to be trained in the martial arts. Lee's first introduction to martial arts was through his father, from whom he learned the fundamentals of Wu-style t'ai chi ch'uan.[33]

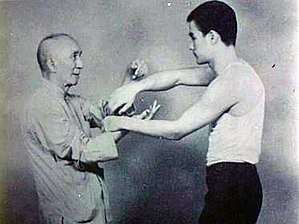

Wing Chun

The largest influence on Lee's martial arts development was his study of Wing Chun. Lee began training in Wing Chun when he was 16 years old under the Wing Chun teacher Ip Man in 1957, after losing several fights with rival gang members. Yip's regular classes generally consisted of the forms practice, chi sao (sticking hands) drills, wooden dummy techniques, and free-sparring.[34] There was no set pattern to the classes.[34] Yip tried to keep his students from fighting in the street gangs of Hong Kong by encouraging them to fight in organized competitions.[35]

After a year into his Wing Chun training, most of Yip Man's other students refused to train with Lee when they learned of his mixed ancestry, as the Chinese were generally against teaching their martial arts techniques to non-Asians.[36][37] Lee's sparring partner, Hawkins Cheung, states, "Probably fewer than six people in the whole Wing Chun clan were personally taught, or even partly taught, by Yip Man".[38] However, Lee showed a keen interest in Wing Chun, and continued to train privately with Ip Man and Wong Shun Leung in 1955.[39] Wan Kam Leung, a student of Wong's, witnessed a sparring bout between Wong and Lee and noted the speed and precision with which Lee was able to deliver his kicks.[40] Lee continued to train with Wong Shun Leung after returning to Hong Kong from America.

Leaving Hong Kong

After attending Tak Sun School (德信學校) (several blocks from his home at 218 Nathan Road, Kowloon), Lee entered the primary school division of the Catholic La Salle College at the age of 12. In 1956, due to poor academic performance and possibly poor conduct, he was transferred to St. Francis Xavier's College (high school), where he would be mentored by Brother Edward, a teacher and coach of the school boxing team. In 1958, Bruce won the Hong Kong schools boxing tournament, knocking out the previous champion in the final.[41]

In the spring of 1959, Lee got into another street fight, and the police were called.[42] Until his late teens, Lee's street fights became more frequent and included beating the son of a feared triad family. Eventually, Lee's father decided his son should leave Hong Kong to pursue a safer and healthier life in the United States. His parents confirmed the police's fear that this time Lee's opponent had an organized crime background and that there was the possibility that a contract was out for his life.

The police detective came and he says "Excuse me Mr. Lee, your son is really fighting bad in school. If he gets into just one more fight I might have to put him in jail".

In April 1959, Lee's parents decided to send him to the United States to stay with his older sister, Agnes Lee (李秋鳳), who was already living with family friends in San Francisco.

New life in America

At the age of 18, Lee returned to the United States. After living in San Francisco for several months, he moved to Seattle in 1959 to continue his high school education, where he also worked for Ruby Chow as a live-in waiter at her restaurant.

Chow's husband was a co-worker and friend of Lee's father. Lee's elder brother Peter Lee (李忠琛) would also join him in Seattle for a short stay before moving on to Minnesota to attend college. In December 1960, Lee completed his high school education and received his diploma from Edison Technical School (now Seattle Central Community College, located on Capitol Hill in Seattle).

In March 1961, Lee enrolled at the University of Washington and studied dramatic arts, philosophy, psychology, and various other subjects.[43][44] Despite what Lee himself and many others have stated, Lee's official major was drama rather than philosophy according to a 1999 article in the university's alumni publication,.[45] He soon met his future wife Linda Emery, a fellow student studying to become a teacher, whom he married in August 1964.

Lee had two children with Linda Emery: Brandon Lee (1965–1993) and Shannon Lee (born 1969).

Martial arts career

Jun Fan Gung Fu

Lee began teaching martial arts in the United States in 1959. He called what he taught Jun Fan Gung Fu (literally Bruce Lee's Kung Fu). It was basically his approach to Wing Chun.[46] Lee taught friends he met in Seattle, starting with Judo practitioner Jesse Glover, who continued to teach some of Lee's early techniques. Taky Kimura became Lee's first Assistant Instructor and continued to teach his art and philosophy after Lee's death.[47] Lee opened his first martial arts school, named the Lee Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute, in Seattle.

Lee dropped out of college in the spring of 1964 and moved to Oakland to live with James Yimm Lee (嚴鏡海). James Lee was twenty years senior to Bruce Lee and a well-known Chinese martial artist in the area. Together, they founded the second Jun Fan martial arts studio in Oakland. James Lee was also responsible for introducing Bruce Lee to Ed Parker, an American martial artist and organizer of the Long Beach International Karate Championships where Bruce Lee was later "discovered" by Hollywood.

Long Beach International Karate Championships

At the invitation of Ed Parker, Lee appeared in the 1964 Long Beach International Karate Championships[48] and performed repetitions of two-finger push-ups (using the thumb and the index finger of one hand) with feet at approximately shoulder-width apart. In the same Long Beach event he also performed the "One inch punch."[49] Lee stood upright, his right foot forward with knees bent slightly, in front of a standing, stationary partner. Lee's right arm was partly extended and his right fist approximately one inch (2.5 cm) away from the partner's chest. Without retracting his right arm, Lee then forcibly delivered the punch to his partner while largely maintaining his posture, sending the partner backwards and falling into a chair said to be placed behind the partner to prevent injury, though his partner's momentum soon caused him to fall to the floor. His volunteer was Bob Baker of Stockton, California. "I told Bruce not to do this type of demonstration again", Baker recalled. "When he punched me that last time, I had to stay home from work because the pain in my chest was unbearable".[50]

It was at the 1964 championships that Lee first met Taekwondo master Jhoon Goo Rhee. The two developed a friendship – a relationship from which they benefited as martial artists. Rhee taught Lee the side kick in detail, and Lee taught Rhee the "non-telegraphic" punch.[51]

Lee appeared at the 1967 Long Beach International Karate Championships and performed various demonstrations, including the famous "unstoppable punch" against USKA world Karate champion Vic Moore.[48] Lee allegedly told Moore that he was going to throw a straight punch to the face, and all he had to do was to try to block it. Lee took several steps back and asked if Moore was ready. When Moore nodded in affirmation, Lee glided towards him until he was within striking range. He then threw a straight punch directly at Moore's face, and stopped before impact. In eight attempts, Moore failed to block any of the punches.[52][53] However, Moore and grandmaster Steve Mohammed claim that Lee had first told Moore that he was going to throw a straight punch to the body, which Moore blocked. Lee attempted another punch, and Moore blocked it as well. The third punch, which Lee threw to Moore's face, did not come nearly within striking distance. Moore claims that Lee never successfully struck Moore but Moore was able to strike Lee after trying on his own. Moore further claims that Bruce Lee said he was the fastest American he's ever seen and that Lee's media crew repeatedly played the one punch towards Moore's face that did not come within striking range, allegedly in an attempt to preserve Lee's superstar image. However, when viewing the video of the demonstration, it is clear that Mohammed and especially Moore were erroneous in their claims.[54]

Fight with Wong Jack Man

In Oakland's Chinatown in 1964, Lee had a controversial private match with Wong Jack Man, a direct student of Ma Kin Fung, known for his mastery of Xingyiquan, Northern Shaolin, and T'ai chi ch'uan. According to Lee, the Chinese community issued an ultimatum to him to stop teaching non-Chinese people. When he refused to comply, he was challenged to a combat match with Wong. The arrangement was that if Lee lost, he would have to shut down his school, while if he won, he would be free to teach white people, or anyone else.[55] Wong denied this, stating that he requested to fight Lee after Lee boasted during one of his demonstrations at a Chinatown theatre that he could beat anyone in San Francisco, and that Wong himself did not discriminate against Whites or other non-Chinese people.[56] Lee commented, "That paper had all the names of the sifu from Chinatown, but they don't scare me".[57]

Individuals known to have witnessed the match include Cadwell, James Lee (Bruce Lee's associate, no relation), and William Chen, a teacher of T'ai chi ch'uan. Wong and William Chen stated that the fight lasted an unusually long 20–25 minutes.[56][58] Wong claims that although he had originally expected a serious but polite bout, Lee aggressively attacked him with intent to kill. When Wong presented the traditional handshake, Lee appeared to accept the greeting, but instead, Lee immediately thrust his hand as a spear aimed at Wong's eyes. Forced to defend his life, Wong nonetheless refrained from striking Lee with killing force when the opportunity presented itself because it could have earned him a prison sentence. The fight ended due to Lee's "unusually winded" condition, as opposed to a decisive blow by either fighter.[56] By contrast, according to Bruce Lee, Linda Lee Cadwell, and James Yimm Lee, the fight lasted a mere 3 minutes with a decisive victory for Lee. In Cadwell's account, "The fight ensued, it was a no-holds-barred fight, it took three minutes. Bruce got this guy down to the ground and said 'Do you give up?' and the man said he gave up".[55]

A couple of weeks after the bout, Lee gave an interview claiming that he had defeated an unnamed challenger, which Wong says was an obvious reference to him.[56][58] In response, Wong published his own account of the fight in the Chinese Pacific Weekly, a Chinese-language newspaper in San Francisco, with an invitation to a public rematch if Lee was not satisfied with the account. Lee did not respond to the invitation despite his reputation for violently responding to every provocation,[56] and there were no further public announcements by either, though Lee continued to teach white people.

Jeet Kune Do

Jeet Kune Do originated in 1967. After filming one season of The Green Hornet, Lee found himself out of work and opened The Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute. The controversial match with Wong Jack Man influenced Lee's philosophy about martial arts. Lee concluded that the fight had lasted too long and that he had failed to live up to his potential using his Wing Chun techniques. He took the view that traditional martial arts techniques were too rigid and formalized to be practical in scenarios of chaotic street fighting. Lee decided to develop a system with an emphasis on "practicality, flexibility, speed, and efficiency". He started to use different methods of training such as weight training for strength, running for endurance, stretching for flexibility, and many others which he constantly adapted, including fencing and basic boxing techniques.

Lee emphasized what he called "the style of no style". This consisted of getting rid of the formalized approach which Lee claimed was indicative of traditional styles. Lee felt that even the system he now called Jun Fan Gung Fu was too restrictive, and it eventually evolved into a philosophy and martial art he would come to call Jeet Kune Do or the Way of the Intercepting Fist. It is a term he would later regret, because Jeet Kune Do implied specific parameters that styles connote, whereas the idea of his martial art was to exist outside of parameters and limitations.[60]

Fitness and nutrition

At 172 cm (5 ft 8 in) and weighing 64 kg (141 lb) at the time,[61] Lee was renowned for his physical fitness and vigor, achieved by using a dedicated fitness regimen to become as strong as possible. After his match with Wong Jack Man in 1965, Lee changed his approach toward martial arts training. Lee felt that many martial artists of his time did not spend enough time on physical conditioning. Lee included all elements of total fitness—muscular strength, muscular endurance, cardiovascular endurance, and flexibility. He used traditional bodybuilding techniques to build some muscle mass, though not overdone, as that could decrease speed or flexibility. At the same time, with respect to balance, Lee maintained that mental and spiritual preparation are fundamental to the success of physical training in martial arts skills. In Tao of Jeet Kune Do he wrote:

Training is one of the most neglected phases of athletics. Too much time is given to the development of skill and too little to the development of the individual for participation. ... JKD, ultimately is not a matter of petty techniques but of highly developed spirituality and physique.[62]

According to Linda Lee Cadwell, soon after he moved to the United States, Lee started to take nutrition seriously and developed an interest in health foods, high-protein drinks, and vitamin and mineral supplements. He later concluded that achieving a high-performance body was akin to maintaining the engine of a high-performance automobile. Allegorically, as one could not keep a car running on low-octane fuels, one could not sustain one's body with a steady diet of junk food, and with "the wrong fuel", one's body would perform sluggishly or sloppily.[63] Lee also avoided baked goods and refined flour, describing them as providing empty calories that did nothing for his body.[64] He was known for being a fan of Asian cuisine for its variety, and often ate meals with a combination of vegetables, rice, and fish, and drank fresh milk.

Acting career

Lee's father Lee Hoi-chuen was a famous Cantonese opera star. Because of this, Lee was introduced into films at a very young age and appeared in several films as a child. Lee had his first role as a baby who was carried onto the stage in the film Golden Gate Girl. By the time he was 18, he had appeared in twenty films.[17]

While in the United States from 1959 to 1964, Lee abandoned thoughts of a film career in favour of pursuing martial arts. However, a martial arts exhibition on Long Beach in 1964 eventually led to the invitation by William Dozier for an audition for a role in the pilot for "Number One Son". The show never aired, but Lee was invited for the role of the sidekick Kato alongside the title character played by Van Williams in the TV series titled The Green Hornet. The show lasted only one season of 26 episodes, from September 1966 to March 1967. Lee and Williams also appeared as their respective characters in three crossover episodes of Batman, another William Dozier-produced television series. This was followed by guest appearances in three television series: Ironside (1967), Here Come the Brides (1969), and Blondie (1969).

At the time, two of Lee's martial arts students were Hollywood script writer Stirling Silliphant and actor James Coburn. In 1969 the three worked on a script for a film called The Silent Flute, and went together on a location hunt to India. The project was not realised at the time, but the 1978 film Circle of Iron, starring David Carradine, was based on the same plot. In 2010, producer Paul Maslansky was reported to have planned and received funding for a film based on the original script for The Silent Flute.[65] In 1969, Lee made a brief appearance in the Silliphant-penned film Marlowe, where he played a henchman hired to intimidate private detective Philip Marlowe, (played by James Garner), by smashing up his office with leaping kicks and flashing punches, only to later accidentally jump off a tall building while trying to kick Marlowe off. The same year he also choreographed fight scenes for The Wrecking Crew starring Dean Martin, Sharon Tate, and featuring Chuck Norris in his first role. In 1970, he was responsible for fight choreography for A Walk in the Spring Rain starring Ingrid Bergman and Anthony Quinn, again written by Silliphant. In 1971, Lee appeared in four episodes of the television series Longstreet, written by Silliphant. Lee played the martial arts instructor of the title character Mike Longstreet (played by James Franciscus), and important aspects of his martial arts philosophy were written into the script.

According to statements made by Lee, and also by Linda Lee Cadwell after Lee's death, in 1971 Lee pitched a television series of his own tentatively titled The Warrior, discussions of which were also confirmed by Warner Bros. During a December 9, 1971 television interview on The Pierre Berton Show, Lee stated that both Paramount and Warner Brothers wanted him "to be in a modernized type of a thing, and that they think the Western idea is out, whereas I want to do the Western".[66] According to Cadwell, however, Lee's concept was retooled and renamed Kung Fu, but Warner Bros. gave Lee no credit.[67] Warner Brothers states that they had for some time been developing an identical concept,[68] created by two writers and producers, Ed Spielman and Howard Friedlander. According to these sources, the reason Lee was not cast was in part because of his ethnicity, but more so because he had a thick accent.[69] The role of the Shaolin monk in the Wild West was eventually awarded to then-non-martial-artist David Carradine. In The Pierre Berton Show interview, Lee stated he understood Warner Brothers' attitudes towards casting in the series: "They think that business-wise it is a risk. I don't blame them. If the situation were reversed, and an American star were to come to Hong Kong, and I was the man with the money, I would have my own concerns as to whether the acceptance would be there".[70]

Hong Kong films and stardom

Producer Fred Weintraub had advised Lee to return to Hong Kong and make a feature film which he could showcase to executives in Hollywood.[71] Not happy with his supporting roles in the US, Lee returned to Hong Kong. Unaware that The Green Hornet had been played to success in Hong Kong and was unofficially referred to as "The Kato Show", he was surprised to be recognized on the street as the star of the show. After negotiating with both Shaw Brothers Studio and Golden Harvest, Lee signed a film contract to star in two films produced by Golden Harvest.

Lee played his first leading role in The Big Boss (1971), which proved to be an enormous box office success across Asia and catapulted him to stardom. He soon followed up with Fist of Fury (1972), which broke the box office records set previously by The Big Boss. Having finished his initial two-year contract, Lee negotiated a new deal with Golden Harvest. Lee later formed his own company, Concord Production Inc. (協和電影公司), with Chow. For his third film, Way of the Dragon (1972), he was given complete control of the film's production as the writer, director, star, and choreographer of the fight scenes. In 1964, at a demonstration in Long Beach, California, Lee had met karate champion Chuck Norris. In Way of the Dragon Lee introduced Norris to moviegoers as his opponent in the final death fight at the Colosseum in Rome, today considered one of Lee's most legendary fight scenes and one of the most memorable fight scenes in martial arts film history.[21] The role had originally been offered to American karate champion Joe Lewis.[72]

From August to October 1972, Lee began work on his fourth Golden Harvest Film, Game of Death. He began filming some scenes, including his fight sequence with 7 ft 2 in (218 cm) American basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, a former student. Production stopped in November 1972 when Warner Brothers offered Lee the opportunity to star in Enter the Dragon, the first film to be produced jointly by Concord, Golden Harvest, and Warner Bros. Filming began in Hong Kong in January 1973. One month into the filming, another production company, Starseas Motion Pictures, promoted Bruce Lee as a leading actor in Fist of Unicorn, although he had merely agreed to choreograph the fight sequences in the film as a favour to his long-time friend Unicorn Chan. Lee planned to sue the production company, but retained his friendship with Chan.[73] However, only a few months after the completion of Enter the Dragon, and six days before its July 26, 1973 release,[74] Lee died. Enter the Dragon would go on to become one of the year's highest-grossing films and cement Lee as a martial arts legend. It was made for US$850,000 in 1973 (equivalent to $4 million adjusted for inflation as of 2007).[75] To date, Enter the Dragon has grossed over $200 million worldwide.[76] The film sparked a brief fad in martial arts, epitomised in songs such as "Kung Fu Fighting" and TV shows like Kung Fu.

Robert Clouse, the director of Enter the Dragon, together with Golden Harvest, revived Lee's unfinished film Game of Death. Lee had shot over 100 minutes of footage, including out-takes, for Game of Death before shooting was stopped to allow him to work on Enter the Dragon. In addition to Abdul-Jabbar, George Lazenby, Hapkido master Ji Han-Jae, and another of Lee's students, Dan Inosanto, were also to appear in the film, which was to culminate in Lee's character, Hai Tien (clad in the now-famous yellow track suit[77][78]) taking on a series of different challengers on each floor as they make their way through a five-level pagoda. In a controversial move, Robert Clouse finished the film using a look-alike and archive footage of Lee from his other films with a new storyline and cast, which was released in 1978. However, the cobbled-together film contained only fifteen minutes of actual footage of Lee (he had printed many unsuccessful takes)[79] while the rest had a Lee look-alike, Kim Tai Chung, and Yuen Biao as stunt double. The unused footage Lee had filmed was recovered 22 years later and included in the documentary Bruce Lee: A Warrior's Journey.[80]

Apart from Game of Death, other future film projects were planned to feature Lee at the time. In 1972, after the success of The Big Boss and Fist of Fury, a third film was planned by Raymond Chow at Golden Harvest to be directed by Lo Wei, titled Yellow-Faced Tiger. However, at the time, Lee decided to direct and produce his own script for Way of the Dragon instead. Although Lee had formed a production company with Raymond Chow, a period film was also planned from September–November 1973 with the competing Shaw Brothers Studio, to be directed by either Chor Yuen or Cheng Kang, and written by Yi Kang and Chang Cheh, titled The Seven Sons of the Jade Dragon.[81] Lee had also worked on several scripts himself. A tape containing a recording of Lee narrating the basic storyline to a film tentatively titled Southern Fist/Northern Leg exists, showing some similarities with the canned script for The Silent Flute (Circle of Iron).[82] Another script had the title Green Bamboo Warrior, set in San Francisco, planned to co-star Bolo Yeung and to be produced by Andrew Vajna who later went on to produce First Blood.[73] Photoshoot costume tests were also organized for some of these planned film projects.

In 2015, Perfect Storm Entertainment and Bruce Lee's daughter, Shannon Lee announced that the series "The Warrior" would be produced and would air on the Cinemax and the filmmaker Justin Lin was chosen to direct the series.[83] Production began on October 22, 2017 in Cape Town, South Africa. The first season will contain 10 episodes.[84]

Artistry

Philosophy

Lee is best known as a martial artist, but he also studied drama and Asian and Western philosophy while a student at the University of Washington and throughout his life. He was well-read and had an extensive library dominated by martial arts subjects and philosophical texts.[85] His own books on martial arts and fighting philosophy are known for their philosophical assertions, both inside and outside of martial arts circles. His eclectic philosophy often mirrored his fighting beliefs, though he was quick to claim that his martial arts were solely a metaphor for such teachings. He believed that any knowledge ultimately led to self-knowledge, and said that his chosen method of self-expression was martial arts.[86] His influences include Taoism, Jiddu Krishnamurti, and Buddhism.[87] Lee's philosophy was very much in opposition to the conservative worldview advocated by Confucianism.[88] John Little states that Lee was an atheist. When asked in 1972 about his religious affiliation, he replied, "none whatsoever",[89] and when asked if he believed in God, he said, "To be perfectly frank, I really do not."[86]

Poetry

Aside from martial arts and philosophy, which focus on the physical aspect and self-consciousness for truths and principles,[90] Lee also wrote poetry that reflected his emotion and a stage in his life collectively.[91] Many forms of art remain concordant with the artist creating them. Lee's principle of self-expression was applied to his poetry as well. His daughter Shannon Lee said, "He did write poetry; he was really the consummate artist."[92] His poetic works were originally handwritten on paper, then later on edited and published, with John Little being the major author (editor), for Bruce Lee's works. Linda Lee Cadwell (Bruce Lee's wife) shared her husband's notes, poems, and experiences with followers. She mentioned "Lee's poems are, by American standards, rather dark--reflecting the deeper, less exposed recesses of the human psyche".[93] Most of Bruce Lee's poems are categorized as anti-poetry or fall into a paradox. The mood in his poems shows the side of the man that can be compared with other poets such as Robert Frost, one of many well-known poets expressing himself with dark poetic works. The paradox taken from the Yin and Yang symbol in martial arts was also integrated into his poetry. His martial arts and philosophy contribute a great part to his poetry. The free verse form of Lee's poetry reflects his famous quote "Be formless … shapeless, like water."[94]

Death

On May 10, 1973, Lee collapsed during an automated dialogue replacement session for Enter the Dragon at Golden Harvest in Hong Kong. Suffering from seizures and headaches, he was immediately rushed to Hong Kong Baptist Hospital, where doctors diagnosed cerebral edema. They were able to reduce the swelling through the administration of mannitol. The headache and cerebral edema that occurred in his first collapse were later repeated on the day of his death.[95]

On July 20, 1973, Lee was in Hong Kong, to have dinner with actor George Lazenby, with whom he intended to make a film. According to Lee's wife Linda, Lee met producer Raymond Chow at 2 p.m. at home to discuss the making of the film Game of Death. They worked until 4 p.m. and then drove together to the home of Lee's colleague Betty Ting Pei, a Taiwanese actress. The three went over the script at Ting's home, and then Chow left to attend a dinner meeting.[96][97]

Later, Lee complained of a headache, and Ting gave him an analgesic, Equagesic, which contained both aspirin and the tranquilizer meprobamate. Around 7:30 p.m., he went to lie down for a nap. When Lee did not come for dinner, producer Raymond Chow came to the apartment, but he was unable to wake Lee up. A doctor was summoned, and spent ten minutes attempting to revive Lee before sending him by ambulance to Queen Elizabeth Hospital. Lee was declared dead on arrival, at the age of 32.

There was no visible external injury; however, according to autopsy reports, Lee's brain had swollen considerably, from 1,400 to 1,575 grams (a 13% increase). The autopsy found Equagesic in his system. On October 15, 2005, Chow stated in an interview that Lee died from an allergic reaction to the tranquilizer meprobamate, the main ingredient in Equagesic, which Chow described as an ingredient commonly used in painkillers. When the doctors announced Lee's death, it was officially ruled a "death by misadventure".[98][99]

Lee's wife Linda returned to her hometown of Seattle, and had Lee's body buried in Lot 276 of Lake View Cemetery in Seattle.[100][101] Pallbearers at Lee's funeral on July 25, 1973, included Taky Kimura, Steve McQueen, James Coburn, Chuck Norris, George Lazenby, Dan Inosanto, Peter Chin, and Lee's brother Robert.[102] Around the time of Lee's death, numerous rumors appeared in the media.[103] Lee's iconic status and untimely death fed many wild rumors and theories. These included murder involving the triads and a supposed curse on him and his family.[104]

Donald Teare, a forensic scientist, recommended by Scotland Yard, who had overseen over 1,000 autopsies, was assigned to the Lee case. His conclusion was "death by misadventure" caused by an acute cerebral edema due to a reaction to compounds present in the combination medication Equagesic.[105] Although there was initial speculation that cannabis found in Lee's stomach may have contributed to his death, Teare refuted this, stating that it would "be both 'irresponsible and irrational' to say that [cannabis] might have triggered either the events of Bruce's collapse on May 10 or his death on July 20".[105] Dr. R. R. Lycette, the clinical pathologist at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, reported at the coroner hearing that the death could not have been caused by cannabis.[105]

At the 1975 San Diego Comic-Con convention, Lee's friend Chuck Norris attributed his death to a reaction to the combination of the muscle-relaxant medication he had been taking since 1968 for a ruptured disc in his back and an "antibiotic" he was given for his headache on the night of his death.[106] In a 2017 episode of the Reelz TV series Autopsy: The Last Hours of..., forensic pathologist Dr. Michael Hunter theorized that Lee died of adrenal crisis brought on by the overuse of cortisone, which Lee had been taking since injuring his back in a 1970 weightlifting mishap.[107] Dr. Hunter believes that Lee's exceptionally strong "drive and ambition" played a fundamental role in the martial artist's ultimate demise.[107]

In a 2018 biography, author Matthew Polly consulted with medical experts and theorized that Lee died from cerebral edema caused by over-exertion and heat stroke; and heat stroke was not considered at the time because it was then a poorly-understood condition.[108] Furthermore, Lee had had his underarm sweat glands removed in late 1972, in the apparent belief that underarm sweat was unphotogenic on film.[107] Polly further theorized that this caused Lee's body to overheat while practicing in hot temperatures on May 10 and July 20, 1973, resulting in heat stroke that in turn exacerbated the cerebral edema that led to his death.[108]

Legacy

Certified instructors

Bruce Lee personally certified only three instructors: Taky Kimura, James Yimm Lee, and Dan Inosanto. Inosanto holds the 3rd rank (Instructor) directly from Bruce Lee in Jeet Kune Do, Jun Fan Gung Fu, and Bruce Lee's Tao of Chinese Gung Fu. Taky Kimura holds a 5th rank in Jun Fan Gung Fu. James Yimm Lee held a 3rd rank in Jun Fan Gung Fu. Ted Wong holds 2nd rank in Jeet Kune Do certified directly by Bruce Lee and was later promoted to Instructor under Dan Inosanto, who felt that Bruce would have wanted to promote him. Other Jeet Kune Do instructors since Lee's death have been certified directly by Dan Inosanto, some with remaining Bruce Lee-signed certificates.

James Yimm Lee, a close friend of Lee, certified a few students including Gary Dill, who studied Jeet Kune Do under James and received permission via a personal letter from him in 1972 to pass on his learning of Jun Fan Gung Fu to others. Taky Kimura, to date, has certified only one person in Jun Fan Gung Fu: his son Andy Kimura. Dan Inosanto continued to teach and certify select students in Jeet Kune Do for over 30 years, making it possible for thousands of martial arts practitioners to trace their training lineage back to Bruce Lee. Prior to his death, Lee told his then only two living instructors Kimura and Inosanto (James Yimm Lee had died in 1972) to dismantle his schools. Both Taky Kimura and Dan Inosanto were allowed to teach small classes thereafter, under the guideline "keep the numbers low, but the quality high".

Bruce also instructed several World Karate Champions including Chuck Norris, Joe Lewis, and Mike Stone. Between the three of them, during their training with Bruce, they won every karate championship in the United States.[109]

In Japan, Junichi Okada is a certified Japanese instructor in Jeet Kune Do.[110]

Hong Kong legacy

There are a number of stories (perhaps apocryphal) surrounding Lee that are still repeated in Hong Kong culture. One is that his early 1970s interview on the TVB show Enjoy Yourself Tonight cleared the busy streets of Hong Kong as everyone was watching the interview at home.

On January 6, 2009, it was announced that Bruce's Hong Kong home (41 Cumberland Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong) will be preserved and transformed into a tourist site by philanthropist Yu Pang-lin.[111][112]

Awards and honours

Bruce Lee was named by Time Magazine as one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century.[10]

In April 2013, he was posthumously awarded the prestigious Founders Award at The Asian Awards.[113]

A Bruce Lee statue was unveiled in Los Angeles' Chinatown on June 15, 2013. It stands at 7-foot (210 cm) tall and was made in Guangzhou, China.[114]

In April 2014, it was announced that Lee would be a featured character in the video game EA Sports UFC, and will be playable in multiple weight classes.[115]

Bruce Lee was voted as the Greatest Movie Fighter Ever in 2014 by the Houston Boxing Hall Of Fame. The HBHOF is a combat sports voting body composed exclusively of current and former fighters and Martial Artists.

Martial arts lineage

Lee was trained in Wu Tai Chi Chuan (also known as Ng-ga) and Jing Mo Tam Tui for the twelve sets. Lee was trained in the martial arts Choy Li Fut, Western Boxing, Épée fencing, Judo, Praying Mantis kung fu, Hsing-I, and Jujitsu.

When Bruce arrived in the US he (already) had training in Wu Style Tai Chi, sometimes in Hong Kong called Ng-ga. And he had of course training in western boxing. He had training in fencing from his brother, that's Epee, that goes from toe to head. He had training obviously in Wing Chun. And the other area was the training he had received in Buk Pie, or Tam Toi, he was twelve sets in Tam Toi. And I believe he had traded with a Choy Li Fut man.

— Danny Inosanto[116]

| Lineage in Wing Chun |

|---|

| Ng Mui |

| Yim Wing Chun |

| Leung Bok-chau |

| Leung Lan-kwai |

| Wong Wah-bo |

| Leung Yee-tai |

| Leung Jan |

| Chan Wah-shun |

| Ip Man (葉問) |

| Bruce Lee |

| Bruce Lee (李小龍) Founder of Jeet Kune Do | |

|---|---|

| Certified by Bruce Lee as instructors of Jeet Kune Do | Taky Kimura James Yimm Lee Dan Inosanto |

| Notable students of Jun Fan/Gung Fu/Jeet Kune Do | Brandon Lee Jesse Glover Dan Inosanto Yorinaga Nakamura Taky Kimura Richard Bustillo Jerry Poteet Ted Wong James Yimm Lee Rusty Stevens Chuck Norris[117] Kareem Abdul-Jabbar James Coburn Joe Lewis Roman Polanski Lee Marvin Stirling Silliphant |

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Marlowe | Winslow Wong | |

| 1971 | The Big Boss | Cheng Chao-an | Also known as Fists of Fury |

| 1972 | Fist of Fury | Chen Zhen | Also known as The Chinese Connection |

| 1972 | Way of the Dragon | Tang Lung | Also known as Return of the Dragon |

| 1972 | Game of Death | Hai Ten | Filming was never completed until after 1978 |

| 1973 | Enter the Dragon | Lee | Posthumous release |

| 1979 | The Real Bruce Lee | Bruce Lee before his death | A post death film about him |

| 1981 | Game of Death II | Also known as Tower of Death. Lee died before production of the film, and his scenes were taken from his other films. |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966–1967 | The Green Hornet | Kato | 26 episodes |

| 1966–1967 | Batman | Kato | 3 episodes |

| 1967 | Ironside | Leon Soo | Episode: "Tagged for Murder" |

| 1969 | Blondie | Karate Instructor | Episode: "Pick on Someone Your Own Size" |

| 1969 | Here Come the Brides | Lin | Episode: "Marriage Chinese Style" |

| 1970–1973 | Enjoy Yourself Tonight | Himself | 6 episodes |

| 1971 | Longstreet | Li Tsung | 4 episodes |

| 1971 | The Pierre Berton Show | Himself |

Advertising

Though Bruce Lee did not appear in commercials during his lifetime, Nokia launched an internet-based campaign in 2008 with staged "documentary-looking" footage of Bruce Lee playing ping-pong with his nunchaku and also igniting matches as they are thrown towards him. The videos went viral on YouTube, creating confusion as some people believed them to be authentic footage.[118]

Bibliography

- Chinese Gung-Fu: The Philosophical Art of Self Defense (Bruce Lee's first book) – 1963

- Tao of Jeet Kune Do (Published posthumously) – 1973

- Bruce Lee's Fighting Method (Published posthumously) – 1978

See also

References

- ↑ "Bruce Lee's residence". scmp.

- ↑ "Bruce Lee". Bruce Lee.

- ↑ Bruce Lee at Hong Kong Cinemagic. (look under the 'nationality' section)

- 1 2 "Awards, Honors, Achievements, and Activities". Los Angeles: Bruce Lee Foundation. Archived from the original on August 5, 2009. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Enter the star of the century". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ↑ "Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do". Bruce Lee Foundation. Archived from the original on July 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Bruce Lee Lives Documentary". Archived from the original on June 29, 2012.

- ↑ "From Icon to Lifestyle, the Marketing of Bruce Lee". The New York Times. December 11, 2009. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Bruce Lee's 70th birth anniversary celebrated". The Hindu. India. November 30, 2010. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- 1 2 Stein, Joel (June 14, 1999). "Bruce Lee: With nothing but his hands, feet and a lot of attitude, he turned the little guy into a tough guy". The Time 100. New York. Archived from the original on June 5, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ↑ Lee 1989, p. 41

- ↑ "Bruce Lee inspired Dev for martial arts". The Times of India. July 1, 2010. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ↑ "How Bruce Lee changed the world-Series". The Hindu. India. May 29, 2011. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ↑ Dennis 1974

- ↑ Bruce Lee Archived November 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. at Hong Kong Cinemagic. (look under the 'nationality' section)

- ↑ Chu, Karen (June 26, 2011). "Proposed Bruce Lee Museum Shelved in Hong Kong". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015.

- 1 2 "Biography". Bruce Lee Foundation. Archived from the original on August 22, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Bruce Lee: Biography". Bruce-lee.ws. Archived from the original on March 12, 2005. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ↑ Description of the parent's racial makeup as described by Robert Lee at minute mark 3:35 in the cable television documentary, First Families: Bruce Lee, which premiered on Fox Family on October 26, 1999.

- 1 2 "Kom Tong Hall at 7 Castle Road, Mid-levels, Hong Kong" (PDF). People's Republic of China. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- 1 2 Lee 1989

- 1 2 Russo, Charles (May 18, 2016). "Was Bruce Lee of English Descent?". VICE Fightland. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016.

- ↑ Russo, Charles (2016). Striking Distance: Bruce Lee and the Dawn of Martial Arts in America (reprint ed.). U of Nebraska Press. p. 50. ISBN 0803290519.

- ↑ Balling, Fredda Dudley (2017). Little, John, ed. Words of the Dragon: Interviews, 1958-1973. Tuttle Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 1462917879.

- ↑ Polly, Matthew (2018). Bruce Lee: A Life. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. pp. 12–15. ISBN 978-1-5011-8762-9.

- ↑ Leibovitz, Liel (1 June 2018). "Bruce Lee Was Jewish!". Tablet. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑ Rogovoy, Seth (5 June 2018). "Wait, Bruce Lee Was Jewish?". The Forward. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ 振藩; Mandarin Pinyin: Zhènfán)Lee 1989

- ↑ Lee 1989, p. 20

- 1 2 3 Bruce Lee: the immortal Dragon, January 29, 2002, A&E Television Networks

- ↑ Lee, Grace (1980). Bruce Lee The Untold Story. United States: CFW Enterprise.

- ↑ "Kom Tong Hall and the Dr Sun Yat-sen Museum". People's Republic of China. January 10, 2005. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ↑ Thomas 1994, p. 14

- 1 2 Black Belt: Bruce Lee Collector's Edition Summer 1993

- ↑ Black Belt: Bruce Lee Collector's Edition Summer 1993, p. 18

- ↑ Thomas 1994, p. 26

- ↑ Sharif 2009, p. 56

- ↑ Black Belt: Bruce Lee Collector's Edition Summer 1993 p. 19

- ↑ Campbell 2006, p. 172

- ↑ Wan Kam Leung recalls Bruce lee fighting with Wong Shun Leung on YouTube (25 July 2009). Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ↑ Thomas 1994, pp29-30

- ↑ Burrows, Alyssa (2002). "Bruce Lee". HistoryLink. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ↑ Little 2001, p. 32

- ↑ Thomas 1994, p. 42

- ↑ "U. of Washington alumni records". Washington.edu. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ↑ "WING CHUN GUNG FU". Hardcore JKD. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ↑ "Bruce Lee Biography". Bruce Lee Foundation. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- 1 2 "2007 Long Beach International Karate Championship". Long Beach International Karate Championship. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ↑ "Two Finger Pushup". Maniac World. Archived from the original on May 21, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ↑ Vaughn 1986, p. 21

- ↑ Nilsson, Thomas (May 1996). "With Bruce Lee: Taekwondo Pioneer Jhoon Rhee Recounts His 10-Year Friendship With the "Dragon"". Black Belt Magazine. 34 (5): 39–43. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ Uyehara 1993, p. 27

- ↑ "Bruce Lee Victor Moore unblockable closing Long Beach International Tournament 60s". YouTube. June 11, 2009. Archived from the original on July 26, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ↑ Vic Moore as interviewed in "GrandMaster Vic Moore: The Man That Fought 'Em ALL!!!". Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- 1 2 Bruce Lee: The Immortal Dragon, January 29, 2002, A&E Television Networks

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dorgan 1980

- ↑ Black Belt: Bruce Lee Collector's Edition, Summer 1993 Rainbow Publications Inc, p. 117

- 1 2 Rossen, Jake (August 10, 2015). "Bruce Lee: The Time Bruce Lee Was Challenged to a Real Fight". Mental Floss. New York, NY. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ↑ Bishop 2004, p. 23

- ↑ Thomas 1994, p. 81

- ↑ "Bruce Lee". china.org.cn. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Martial Art Disciplines at Hybrid Martial Arts Academy". Hybrid Martial Art. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ↑ Little 1998, p. 162

- ↑ Little 1998, p. 163

- ↑ McNary, Dave (April 15, 2010). "Bruce Lee's 'Flute' heads to bigscreen – Entertainment News, Film News, Media". Variety. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ↑ From The Pierre Berton Show on YouTube December 9, 1971 (comments at 7:10 of part 2)

- ↑ Lee 1975a

- ↑ Bleecker, Tom (1996). Unsettled Matters. The Life & Death of Bruce Lee. Gilderoy Publications

- ↑ "From Grasshopper to Caine" on YouTube

- ↑ From The Pierre Berton Show on YouTube December 9, 1971 (comments near end of part 2 & early in part 3)

- ↑ Tale of the Dragon (Channel 4), directed by Jess Search

- ↑ Thomas, B. (1994) Bruce Lee Fighting Spirit. Berkeley: Frog Ltd.

- 1 2 Thomas, B. (2003) Bruce Lee Fighting Words. Berkeley: Frog Ltd.

- ↑ Enter the Dragon on IMDb

- ↑ "Inflation Calculator". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Archived from the original on May 29, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ↑ Stein, Joel (June 14, 1999). "The Gladiator BRUCE LEE". TIME. p. 3. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ↑ Film producer Andre Morgan, who worked with Lee on the set of Game of Death, recalls that a choice had to be made from what was made available: a yellow suit or a black suit. The yellow suit was chosen because it allowed a footprint from a kick to be seen on film in a fighting scene with Kareem.

- ↑ Why Lee wore a yellow suit Archived November 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Bruce Lee, the Legend, 1977, Paragon Films, Ltd., 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment

- ↑ Bruce Lee: A Warrior's Journey on IMDb

- ↑ "Shaw Brothers Film Project". Archived from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- ↑ Bruce Lee The Man & The Legend (Documentary, Golden Harvest, 1973)

- ↑ Andreeva, Nellie (21 May 2015). "Cinemax Developing Bruce Lee-Inspired Crime Drama 'Warrior' From Justin Lin".

- ↑ Andreeva, Nellie (11 October 2017). "'Warrior': Cinemax Sets Cast & Director For Bruce Lee-Inspired Martial Arts Series".

- ↑ "INSIDE BRUCE LEE'S PERSONAL LIBRARY". houseofbrucelee.blogspot.tw.

- 1 2 Little 1996, p. 122

- ↑ Bruce Lee: A Warrior's Journey at 31m45s

- ↑ Bolelli 2008, p. 161

- ↑ Little 1996, p. 128

- ↑ Lee, Bruce (1996). John Little, ed. The Warrior Within. Martial arts-Philosophy: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-8092-3194-8.

- ↑ Lee, Bruce; Linda Lee Cadwell (1999). John Little, ed. Bruce Lee Artist of Life (Book). Tuttle. pp. 93–116. ISBN 978-0-8048-3263-2.

- ↑ Lee, Shannon. "Bruce Lee's Poetry: Shannon Lee reads one of her father's handwritten poems". Poetry. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ↑ Lee, Bruce; Linda Lee Cadwell (1999). "Part 4 Poetry". In John Little. Bruce Lee Artist of Life (Book). Martial Arts: Tuttle. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8048-3263-2.

- ↑ John Little (1996). "Five: The Running Water". In John Little. The Warrior Within (Book). Martial arts-Philosophy: McGraw-Hill. p. 43. ISBN 0-8092-3194-8.

- ↑ Thomas 1994

- ↑ Campbell 2006, p. 205

- ↑ Lee 1989, pp. 156–157

- ↑ Campbell 2006, p. 206

- ↑ "Bruce Lee died of seizure?". The Hindu. India. February 26, 2006. Archived from the original on August 29, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ↑ Lakeview Cemetery website. Archived November 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Search for Lee. Only use last name.

- ↑ "Bruce Lee (1940-1973) - Find A Grave Memorial". www.findagrave.com. Find A Grave. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "Lee, Bruce (1940-1973), Martial Arts Master and Film Maker - HistoryLink.org". www.historylink.org.

- ↑ SHIH, LEE HAN. "The Life of the Dragon" (*Special to asia!). Lee Han Shih is the founder, publisher and editor of asia! Magazine. asia! Magazine. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ↑ Bishop 2004, p. 157

- 1 2 3 Thomas 1994, p. 209

- ↑ Chuck Norris Explains What Really Killed Bruce Lee At The 1975 San Diego Comic-Con Convention Archived November 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 "Autopsy: The Last Hours of Bruce Lee." Autopsy: The Last Hours of.... Nar. Eric Meyers. Exec. Prod. Ed Taylor and Michael Kelpie. Reelz, 15 Jul. 2017. Television.

- 1 2 Polly 2018, p. 473-475.

- ↑ Little 2001, p. 211

- ↑ "V6 Okada Junichi now a martial arts instructor". Tokyo Hive. September 10, 2010. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Bruce Lee's home to become a museum". The Hollywood Reporter. January 6, 2009. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Bruce Lee 35th anniversary". The Hindu. India. July 19, 2008. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Special Report: Asian Awards 2013". April 18, 2013.

- ↑ Bruce Lee statue unveiled in L.A.'s Chinatown Archived June 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine., Los Angeles Times, June 16, 2013

- ↑ Jason Nawara (April 6, 2014). "Bruce Lee revealed as the hidden EA UFC character, release date confirmed". mmanuts.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ↑ Bruce Lee's Jeet Kune Do, 1995 Legacy Productions, New Zealand.

- ↑ Lee 1989, p. 83

- ↑ Agency.Asia. "Agency.Asia - JWT Beijing and Shanghai". agency.asia.

Bibliography

- Bishop, James (2004). Bruce Lee: Dynamic Becoming. Dallas: Promethean Press. ISBN 0-9734054-0-6.

- Bolelli, Daniele (2008). On the Warrior's Path. Blue Snake Books. ISBN 1-58394-219-X.

- Campbell, Sid (2003). The Dragon and the Tiger: The Birth of Bruce Lee's Jeet Kune Do. 1 (illustrated ed.). Frog Books. ISBN 1-58394-089-8.

- Campbell, Sid (2006). Remembering the master (illustrated ed.). Blue Snake Books. ISBN 1-58394-148-7.

- Clouse, Robert (1988). Bruce Lee: The Biography (illustrated ed.). Unique Publications. ISBN 0-86568-133-3.

- Dennis, Felix (1974). Bruce Lee, King of Kung-Fu (illustrated ed.). Wildwood House. ISBN 0-7045-0121-X.

- Dorgan, Michael (1980). Bruce Lee's Toughest Fight. EBM Kung Fu Academy. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- Glover, Jesse R. (1976). Bruce Lee Between Win Chun and Jeet Kune Do. Unspecified vendor. ISBN 0-9602328-0-X.

- Lee, Bruce (1975). Tao of Jeet Kune Do (reprint ed.). Ohara Publications. ISBN 0-89750-048-2.

- Lee, Bruce (2008). M. Uyehara, ed. Bruce Lee's Fighting Method: The Complete Edition (illustrated ed.). Black Belt Communications. ISBN 0-89750-170-5.

- Lee, Linda (1975a). Bruce Lee: the man only I knew. Warner Paperback Library. ISBN 0-446-78774-4.

- Lee, Linda (1989). The Bruce Lee Story. United States: Ohara Publications. ISBN 0-89750-121-7.

- Little, John (2001). Bruce Lee: Artist of Life. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3263-3.

- Little, John (1996). The Warrior Within – The philosophies of Bruce Lee to better understand the world around you and achieve a rewarding life (illustrated ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-8092-3194-8.

- Little, John (1997). Words of the Dragon: Interviews 1958–1973 (Bruce Lee). Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3133-5.

- Little, John (1997a). Jeet Kune Do: Bruce Lee's Commentaries on the Martial Way (illustrated ed.). Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3132-7.

- Little, John (1997b). The tao of gung fu: a study in the way of Chinese martial art. Bruce Lee Library. 2 (illustrated ed.). Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3110-6.

- Little, John (1998). Bruce Lee: The Art of Expressing the Human Body. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3129-1.

- Little, John (2002). Striking Thoughts: Bruce Lee's Wisdom for Daily Living (illustrated ed.). Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3471-7.

- Polly, Matthew (2018). Bruce Lee: A Life. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. pp. 12–15. ISBN 978-1-5011-8762-9.

- Sharif, Sulaiman (2009). 50 Martial Arts Myths. new media entertainment ltd. ISBN 0-9677546-2-3.

- Thomas, Bruce (1994). Bruce Lee: Fighting Spirit: a Biography. Berkeley, California: Frog, Ltd. ISBN 1-883319-25-0.

- Thomas, Bruce (2006). Immortal Combat: Portrait of a True Warrior (illustrated ed.). Blue Snake Books. ISBN 1-58394-173-8.

- Uyehara, Mitoshi (1993). Bruce Lee: the incomparable fighter (illustrated ed.). Black Belt Communications. ISBN 0-89750-120-9.

- Vaughn, Jack (1986). The Legendary Bruce Lee. Black Belt Communications. ISBN 0-89750-106-3.

- Yılmaz, Yüksel (2000). Dövüş Sanatlarının Temel İlkeleri, İstanbul, Turkey: Beyaz Yayınları,

ISBN 975-8261-87-8. templatestyles stripmarker in

|title=at position 73 (help) - Yılmaz, Yüksel (2008). Jeet Kune Do'nun Felsefesi, İstanbul, Turkey: Yalın Yayıncılık,

ISBN 978-9944-313-67-4. templatestyles stripmarker in

|title=at position 67 (help)

External links

![]()

![]()

- Bruce Lee Foundation

- Tap of Jeet Kune Do PDF

- Be Water, My Friend - Bruce Lee

- Bruce Lee on IMDb

- Bruce Lee at the Hong Kong Movie DataBase

- Bruce Lee at AllMovie

- Bruce Lee at Rotten Tomatoes

- Article on Bruce Lee and bodybuilding

- "Bruce Lee". Find a Grave. Retrieved January 20, 2016.