Broad-tailed hummingbird

| Broad-tailed hummingbird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult male at a feeder | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Apodiformes |

| Family: | Trochilidae |

| Genus: | Selasphorus |

| Species: | S. platycercus |

| Binomial name | |

| Selasphorus platycercus (Swainson, 1827) | |

The broad-tailed hummingbird (Selasphorus platycercus) is a medium-sized hummingbird species found in the highland regions, ranging from western USA to Guatemala.[2]

Description

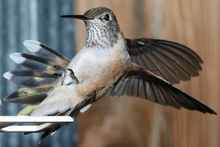

Medium in size, the broad-tailed hummingbird is 4 inches (10 cm) in length and possesses an overall wingspan of 5.25 inches (13.3 cm). Weighing around 3.6 grams (0.13 oz), the female tends to be slightly larger than the male.[3][4] Adults of both gender show an iridescent green back, white eye ring and a rounded black tail projecting beyond their wing tips, from which their name was inspired.[3][4]

This species shows sexual dimorphism, which means that male and female have different characteristics. The male possesses a characteristic bright rose-red gorget, which is not to be confused with the ruby-throated hummingbird gorget. A good identification characteristic to avoid confusion in the field is the white eye ring which is only present on broad-tailed hummingbirds.[3] The female can be distinguished from the male by her paler colouration, her cinnamon flanks, and spotted cheeks which are lacking in the male.[3][5] Aging hummingbirds can be quite difficult in the field but young have been found to have corrugation, little striated formation, covering almost half of their upper bill, which is not present in adult birds.[6]

Taxonomy

The broad-tailed hummingbird, also knows has Selasphorus platycercus , is a member of the order Apodiformes, in the family Trochilidae. Hummingbird taxonomy has not been extensively studied but to aid in its phylogenic division, McGuire (2007) divided the family into nine clades. In this classification, the broad-tailed hummingbird was found to be a member of the Bee group and included in the Selasphorus genus. This genus is composed of 6 members taxonomically distinguished based on colour characteristics[7][8][9]. This genus is characterized by hummingbirds with a plumage containing rufous colouration and a displaying gorget on the males, ranging from orange all the way to purple.[8]

Members of this genus includes[10][9]:

Selasphorus sasin : Allen's Hummingbird

Selasphorus rufus : Rufous Hummingbird

Selasphorus scintilla : Scintillant Hummingbird

Selasphorus ardens : Glow-throated Hummingbird

Selasphorus flammula :Volcano Hummingbird

On a geographic scale the genus Selasphorus can be subdivided into 2 groups of species; a group which live in North America and a group living in the South America in Costa Rica and Panama region[8].

Habitat and distribution

Habitat

This hummingbird can be found in high elevation areas ranging from 1800 m to 4100 m in altitude, depending on the season and region it is found in. This bird is frequently seen in the understory or under trees canopy of pine and oak woodland. This hummingbird can also be found in open areas with flowers or in grasslands where tree and shrub are present[2][5]. Its breeding habitat is mainly composed of subalpine meadows, foothills, montane valleys and strands of aspen or spruce[11][12].

Distribution

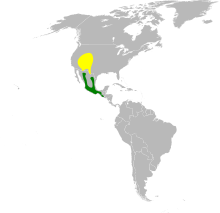

The broad-tailed hummingbird is found all the way from Guatemala to Mexico and Western USA depending on the time of the year their distribution varies across those areas[13][14].The resident population is mainly found in the high western mountain of Guatemala[2][5].

Migration

This species has been found to be a good example of partial migration behaviour. This behaviour implies that some members of the same species will migrate whereas others will remain as a resident to a specific site [13]. The migratory route used by the broad-tailed hummingbird remains unknown to this day. However, it has been well established that the migrating populations winter in southern Mexico or Guatemala and fly to their breeding area which ranges from central Mexico to western USA during the spring migration[11][13][12]. Males have been found to be the first to arrive to the breeding range follow by the older female [11][4]. The fall migration brings both groups to go back to the southern part of their range [14].

Behavior

Vocalizations

The broad-tailed hummingbird produces several different sound patterns. This bird's call sounds like a sharp “cheet”, which is repeated “cheet cheet cheet cheet...” etc[2][5]. Hummingbird wing beats have also been found to be a communication signal. These birds produce two different types of sound using their wing beat. The first one is called “wing hum” and is simply produced when the hummingbird flies. This type of wing beat has a sound that ranges from 35 to 100 Hz, and both sexes are able to produce it for communication. The second one is named “wing trills” and is mostly produced by the male hummingbird[15]. This wing trill produces a buzzing sound and can be heard 50 m away by other males and 75 m away by other females.[16] This sound is produced when air go on their thin 9th and 10th primary feathers.[15] To understand the purpuse of this sound an experiment was performed. This experiments showed that birds without this sound were found to lose their territory more easily to other birds. The purpose of the trill sound in males has then been associated with territory defence during courtship.[16]

Diet

Has explained by Lyon (1973), the diet of the broad-tailed hummingbirds consists mainly of nectar of plants that are “hummingbird-flowered”. Hummingbird-flowered plant are flowers that are mainly pollinated by hummingbird. These types of flower are characterised by their great nectar production and red corollas aboring a tubular shape, for example Aquilegia elegantula . Hummingbirds can also feed on flowers that are insect pollinated when resources become rare. A good example of a flower that is use as alternative nectar source for hummingbird is the Iris flower which is usually bee pollinated , but can also be use by hummingbirds[4][17]. Apart from nectar, the broad-tailed hummingbird can also forage on small insects , like spiders on plant leaves and can use tree sap has an alternative to nectar[4].

Reproduction

Breeding site

The broad-tailed hummingbird has a promiscuous mating system, which means that male and female will have several different partners over their lifespan and won't form a pair bond[12]. For migratory hummingbirds, males tend to arrive earlier to breeding grounds than females to secure a favourable territory[18]. Males will tend to defend a territory, by producing a trill sound with their wing, which contains abundant food resources, to increase their chance to attract a possible mate [16]. The reproduction time for the broad-tailed hummingbirds correlated with the time flower production is at is peak [18]. Monitoring of broad-tailed hummingbirds have shown that the first females to arrive to the breeding grounds are the oldest individuals, which have more experience in migration[11].

Courtship

Male perform an aerial display to impress females during the breeding season. Males will fly high in the sky and dive down while producing a trill sound with their wings to impress the female. However, during aerial performance the male can lose sight of the female and hover high in the sky in a stationary position to look around for his possible mate[19].

Nest construction

In 70 % of cases, females will tend to go back to their nest site from one year to the next based on a study done Colorado. It has been demonstrated that females will reuse their nest depending on the previous year nesting success obtained at this site[11]. Females build their nest alone, without the male help. The overall nest construction may take around 4 to 5 days[4].The nest has an overall cup shape and is stuck to a tree branch with spider webs, camouflaged by the addition of an external layer of lichen, moss, and tree material [20]. Nest material can be stolen by other females for the construction of their own nest[21].

Brooding

The female will lay two white eggs of around 1.2-1.5 cm in length and incubate them alone for around 16 to 19 days[19]. Nest cup diameter increases as the chicks age [20]. Chicks are altricial, naked and helpless, at their hatch, it will take around 10 to 12 days for them to be feathered [4]. The female will stay with the fledged young for a long period which can extend several weeks[12].

Conservation status

This species conservation status is “Least Concern ” which mean that it is not endangered, considering it wide range and abondant population size.[22] It appears to be able to be well-adapted to human-modified habitats and is frequents in shade coffee plantation.[23]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Selasphorus platycercus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Howell, Steve N. G.; Webb, Sophie (1995-03-30). A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780198540120.

- 1 2 3 4 Sibley, David Allen (2016). The sibley field guide to bird of eastern North America. United State: Alfred A.Knopf. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-307-95791-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Camfield, A. F., W. A. Calder, and L. L. Calder (2013). Broad-tailed Hummingbird (Selasphorus platycercus), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.2173/bna.16

- 1 2 3 4 Vallely AC, Dyer D. Birds of Central America : Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama [Internet]. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 2018. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1822250 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/61317/http://public.eblib.com/choice/PublicFullRecord.aspx?p=5520554

- ↑ Francisco, S. (1997). The timing and reliability of bill corrugations for ageing hummingbirds. Western Birds, 28, 13-18.

- ↑ McGuire, Jimmy A.; Witt, Christopher C.; Altshuler, Douglas L.; Remsen, J. V. (2007-10-01). "Phylogenetic Systematics and Biogeography of Hummingbirds: Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood Analyses of Partitioned Data and Selection of an Appropriate Partitioning Strategy". Systematic Biology. 56 (5): 837–856. doi:10.1080/10635150701656360. ISSN 1076-836X.

- 1 2 3 Stiles, F. Gary (1983). "Systematics of the Southern Forms of Selasphorus (Trochilidae)". The Auk. 100 (2): 311–325.

- 1 2 Abrahamczyk, Stefan; Renner, Susanne S. (2015-06-10). "The temporal build-up of hummingbird/plant mutualisms in North America and temperate South America". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 15 (1). doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0388-z. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 4460853. PMID 26058608.

- ↑ "ITIS Standard Report Page: Selasphorus". www.itis.gov. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Calder, William A.; Waser, Nickolas M.; Hiebert, Sara M.; Inouye, David W.; Miller, Sarah (1983-02). "Site-fidelity, longevity, and population dynamics of broad-tailed hummingbirds: a ten year study". Oecologia. 56 (2–3): 359–364. doi:10.1007/bf00379713. ISSN 0029-8549. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Oyler-McCance, Sara J.; Fike, Jennifer A.; Talley-Farnham, Tiffany; Engelman, Tena; Engelman, Fred (2011-01-21). "Characterization of ten microsatellite loci in the Broad-tailed Hummingbird (Selasphorus platycercus)". Conservation Genetics Resources. 3 (2): 351–353. doi:10.1007/s12686-010-9360-9. ISSN 1877-7252.

- 1 2 3 Malpica, Andreia; Ornelas, Juan Francisco (2014-01-06). "Postglacial northward expansion and genetic differentiation between migratory and sedentary populations of the broad-tailed hummingbird (Selasphorus platycercus)". Molecular Ecology. 23 (2): 435–452. doi:10.1111/mec.12614. ISSN 0962-1083.

- 1 2 Webmaster, David Ratz. "Broad-tailed Hummingbird - Montana Field Guide". Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- 1 2 HUNTER, TODD A. (2008-07). "ON THE ROLE OF WING SOUNDS IN HUMMINGBIRD COMMUNICATION". The Auk. 125 (3): 532–541. doi:10.1525/auk.2008.06222. ISSN 0004-8038. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 Miller, Sarah J.; Inouye, David W. (1983-08). "Roles of the wing whistle in the territorial behaviour of male broad-tailed hummingbirds (Selasphorus platycercus)". Animal Behaviour. 31 (3): 689–700. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(83)80224-3. ISSN 0003-3472. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Lyon, David L. (1973). "Territorial and Feeding Activity of Broad-Tailed Hummingbirds (Selasphorus platycercus) in Iris missouriensis". The Condor. 75 (3): 346–349. doi:10.2307/1366178.

- 1 2 Waser, Nickolas M. (1976). "Food Supply and Nest Timing of Broad-Tailed Hummingbirds in the Rocky Mountains". The Condor. 78 (1): 133–135. doi:10.2307/1366943.

- 1 2 "Broad-tailed Hummingbird Life History, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- 1 2 Calder, William A. (1973-01). "Microhabitat Selection During Nesting of Hummingbirds in the Rocky Mountains". Ecology. 54 (1): 127–134. doi:10.2307/1934381. ISSN 0012-9658. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Calder, William A. (1972). "Piracy of Nesting Materials from and by the Broad-Tailed Hummingbird". The Condor. 74 (4): 485–485. doi:10.2307/1365912.

- ↑ "Selasphorus platycercus (Broad-tailed Hummingbird)". www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ↑ Herrera et al. (2006)

Further reading

- Abrahamczyk S, Renner SSJBEB. 2015. The temporal build-up of hummingbird/plant mutualisms in North America and temperate South America. Evolutionary Biology.[accessed 2018 Oct 06]; 15(1):104. DOI: 10.1186/s12862-015-0388-z.

- BirdLife International. 2016. Selasphorus platycercus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016. [accessed 2018 Oct 13]. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22688293A93190741.en.

- Calder WA. 1972. Piracy of Nesting Materials from and by the Broad-Tailed Hummingbird. The Condor.[accessed 2018 Oct 07]; 74(4):485-485. DOI: 10.2307/1365912.

- Calder WA. 1973. Microhabitat Selection During Nesting of Hummingbirds in the Rocky Mountains. Ecology.[accessed 2018 Oct 07]; 54(1):127-134. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1934381.

- Calder WA, Waser NM, Hiebert SM, Inouye DW, Miller SJO. 1983. Site-fidelity, longevity, and population dynamics of broad-tailed hummingbirds: a ten year study. [accessed 2018 Oct 06]; 56(2):359-364. DOI:10.1007/BF00379713.

- Camfield, A. F., W. A. Calder, and L. L. Calder (2013). Broad-tailed Hummingbird (Selasphorus platycercus), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. [accessed 2018 Oct 06]; https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.2173/bna.16.

- Francisco SJWB. 1997. The timing and reliability of bill corrugations for ageing hummingbirds. [accessed 2018 Oct 02]; 28:13-18.https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/wb/v28n01/p0013-p0018.pdf.

- Herrera N, Rivera R, Portillo RI, Rodríguez WJBSX. 2006. Nuevos registros para la avifauna de El Salvador. [accessed 2018 Oct 07]; 1-19. http://sao.org.co/publicaciones/boletinsao/01-Herrera.etal.RecordsSalvador.pdf.

- Howell SNG, Webb S. A. 1995. Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford; [accessed 2018 Oct 07]. https://books.google.fr/books?id=Sklz7tAUa4IC.

- Hunter TA. 2008. On the role of wing sounds in hummingbird communication - Sobre el Rol del Sonido de las Alas en la Comunicacion de los Picaflores. The Auk.[accessed 2018 Oct 01]; 125(3):532-541. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/auk.2008.06222.

- ITIS Standard Report Page. Selasphorus.[accessed 2018 Oct 07]. www.itis.gov.

- Lyon DL. 1973. Territorial and Feeding Activity of Broad-Tailed Hummingbirds (Selasphorus platycercus) in Iris missouriensis. The Condor .[accessed 2018 Oct 07]; 75(3):346-349. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1366178.

- Malpica A, Ornelas JF. 2014. Postglacial northward expansion and genetic differentiation between migratory and sedentary populations of the broad‐tailed hummingbird (Selasphorus platycercus). Molecular Ecology .[accessed 2018 Oct 06]; 23(2):435-452. DOI: 10.1111/mec.12614.

- McGuire JA, Witt CC, Altshuler DL, Remsen JV. 2007. Phylogenetic Systematics and Biogeography of Hummingbirds: Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood Analyses of Partitioned Data and Selection of an Appropriate Partitioning Strategy. Systematic Biology .[accessed 2018 Oct 07]; 56(5):837-856. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150701656360.

- Miller SJ, Inouye DW. 1983. Roles of the wing whistle in the territorial behaviour of male broad-tailed hummingbirds (Selasphorus platycercus). Animal Behaviour .[accessed 2018 Oct 01]; 31(3):689-700.DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(83)80224-3.

- Oyler-McCance SJ, Fike JA, Talley-Farnham T, Engelman T, Engelman FJCGR. 2011. Characterization of ten microsatellite loci in the Broad-tailed Hummingbird (Selasphorus platycercus). Conservation genetics resources.[accessed 2018 Oct 06]; 3(2):351-353. DOI: 10.1007/s12686-010-9360-9.

- Ratz D. Broad-tailed Hummingbird — Selasphorus platycercus. Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks:[accessed 2018 Oct 07]. http://FieldGuide.mt.gov/speciesDetail.aspx?elcode=ABNUC51010.

- Sibley DA. 2016. The sibley field guide to bird of eastern North America. United State: Alfred A.Knopf. p. 221.

- Stiles FG. 1983. Systematics of the Southern Forms of Selasphorus (Trochilidae). The Auk.[accessed 2018 Oct 06]; 100(2):311-325. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4086527.

- All About Birds.Broad-tailed Hummingbird. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. [accessed 2018 Oct 06]. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Broad-tailed_Hummingbird/lifehistory.

- Vallely AC, Dyer D. ; 2018. Birds of Central America : Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [accessed 2018 Oct 07]. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1822250.

- Waser NM. 1976. Food Supply and Nest Timing of Broad-Tailed Hummingbirds in the Rocky Mountains. The Condor. [accessed 2018 Oct 07]; 78(1):133-135. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1366943.

External links

- Broad-tailed hummingbird nest with chicks - Birds of North America

- Broad-tailed hummingbird photo gallery