Bower Manuscript

The Bower Manuscript is an early birch bark document, dated to the Gupta era (between the 4th and the 6th century). This Sanskrit language manuscript is written in the Late Brahmi script, and contains some Prakrit.[1][2] It is an Indian text, one of the oldest manuscripts known to have survived into the modern era, that was discovered near a ruined Buddhist monastery near Kuchar in Chinese Turkestan.[3]

The manuscript is notable as a benchmark for ancient literary tradition in India, and the evidence of the spread and sharing of ideas in ancient times between India, China and central Asia.[3] It is also notable for preserving one of the earliest treatises on Indian medicine (Ayurveda). Rudolf Hoernle (1910) suggested that the text of the manuscript contains excerpts of the (otherwise unknown) Bheda Samhita on medicine.[4] The medical parts (I-III) constitute may be based on similar types of medical writings antedating the composition of the saṃhitās of Caraka, Suśruta, and as such rank with the earliest surviving texts on Ayurveda.

It is today preserved as part of the collections of the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The Bower Manuscript in reality is a collection of seven distinct manuscripts, or it may be called a collective manuscript of seven parts.

Discovery and edition

The Bower Manuscript is named after Hamilton Bower, the British Army intelligence officer who obtained it from a local inhabitant in Kucha early in 1890, while on a confidential mission for the government of British India. Bower took the MS to Simla on his return, whence it was forwarded to Colonel James Waterhouse, the then the President of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Waterhouse exhibited the manuscript at the monthly meeting of the Society on 5 November 5, 1890.

After the meeting some attempts were made to decipher the MS, but they proved unsuccessful. German Indologist Georg Buhler succeeded in reading and translating two leaves of the MS, reproduced in the form of heliogravures in the Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

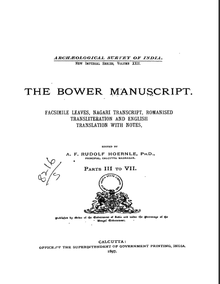

Immediately after his return to India in February 1891, A. F. R. Hoernle began to study the MS. He presented the first decipherment two months later, at the meeting of the Society in April 1891. Between 1893 and 1897 Hoernle published a complete edition of the text, featuring an annotated English translation and illustrated facsimile plates. A Sanskrit Index was published in 1908, and a revised translation of the medical portions (I, II, and III) in 1909; the Introduction appeared in 1912.

The discovery of the Bower Manuscript caught the attentions of the outward-looking European powers, arousing further interest in the region of its discovery and proving a major stimulus in the development of the Great Game. Hoernle claimed that "it was the discovery of the Bower manuscript and its publication in Calcutta which started the whole modern movement of archaeological exploration of Eastern Turkestan".[5]

Description and dating

The 'Bower Manuscript' is in fact a collation of two manuscripts, a larger and a smaller one. The larger manuscript is itself a convolute of six smaller manuscripts, which are separately paginated. These seven constituent manuscripts are numbered as parts I to VII in Hoernle's edition.

The text is written on 51 pages of birch bark leaves of an oblong shape, in the form of those of an Indian pothī. The birch bark of the large portion of the manuscript is of a quality much inferior to that of the smaller portion. The hole for the passage of the binding string is placed about the middle of the left half of the leaves. This placement of the string hole and the oblong form of the leaves point to an imitation of palm leaf pothīs from Southern India by the scribes of Kucā.

The seven parts of the manuscript are written in an essentially identical script, the Gupta Brahmi script, which places the manuscript in the Gupta era (4th to 6th centuries). Hoernle placed the ms. in the 4th century on grounds of paleography, but palaeographical studies by Dani (1986) and especially Sander (1987) suggest a date of about the first half of the 6th century.

Hoernle distinguished four scribes who wrote parts I-III, part IV, parts V and VII and part VI, respectively. He identified the first and third of these as natives of India who had migrated to Kucā. To judge from the style of writing, the scribe of parts I - III originally came from the northern, the two scribes of parts V-VII from the southern part of the northern area of the Indian Gupta script. The writer of part IV may have been a native of Eastern Turkestan.

The script of the Bower MS are written is a type of Late Brahmi script.[3] There is an influence of Prakrit, which is far more pronounced in the more popular treatises on divination and incantation in parts IV-VII than in the more scientific medical treatises of parts I-III.

Contents

The text consists of seven separate and different treatises, of which three on Ayurvedic medicine, two on divination, and two on magical incantations to prevent snakebite.[6] The three medicinal treatises contain content that is also found in the ancient Indian text called the Caraka Samhita.[6]

- Parts I to III, the three medical treatises of the collection, comprise a total of 1,323 verses and some prose; ... It is evident from this familiarity with metrical writing that the author of the three medical treatises was well versed in Sanskrit composition. The author of parts IV-VII was not conversant with scholarly Sanskrit; these treatises are written, in a mixed type of language.

- Part I opens with a flowery description of the Himalayas, where a group of munis reside, interested in the names and properties of medicinal plants. Mentioned by name are the following sages: Ātreya, Hārīta, Parāśara, Bhela, Garga, Śāmbavya, Suśruta, Vasiṣṭha, Karāla, and Kāpya. Suśruta, whose curiosity is aroused by a particular plant, approaches muni Kāśirāja, enquiring about the nature of this plant. Kāśīrāja, granting his request, tells him about the origin of the plant, which proves to be garlic (Sanskrit laśuna), its properties and uses. The section on garlic consists of 43 verses in poetic meter. This section is also notable for mentioning the ancient Indian tradition of "garlic festival", as well as a mention of sage Sushruta in Benares (Varanasi).[6]

- Part II, which opens with a salutation addressed to the Tathāgatas, contains, as stated by the author, the Navanītaka, a standard manual (siddhasaṃkarṣa).[7]

- Part III is a fragment of a formulary, the contents of which correspond to chapters one to three of part II.[8]

- Parts IV and V contain two short manuals of Pāśakakevalī, or cubomancy, i.e., the art of foretelling a person's future by means of the cast of dice. These parts of the MS are notable due for having no relevance to medicine or healing.

- Parts VI and VII contain two different portions of the same text, the Mahāmāyurī, Vidyārājñī, a Buddhist dhāraṇī that protects against snake-bite and other evils.[9]

According to G.J. Meulenbeld: "An important peculiarity of the Bower MS consists of its varying attitude towards the number of the doṣas [humours]. In many instances it accepts the traditional number of three, vāta, pitta, and kapha, but in a smaller number of passages it also appears to accept blood (rakta) as a doṣa."[10]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bower Manuscript. |

- ↑ Sircar, D. C. (31 December 1996). Indian Epigraphy. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 107. ISBN 978-81-208-1166-9.

- ↑ Callewaert, Winand M. (1983). Bhagavadgītānuvāda: A Study in the Transcultural Translation. New Delhi: Biblia Impex. p. 17. OCLC 11533580.

- 1 2 3 Mirsky, Jeannette (October 1998). Sir Aurel Stein: Archaeological Explorer. University of Chicago Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-226-53177-9.

- ↑ Hoernle, A. F. Rudolf (July 1910). "The Bheda Samhita in the Bower Manuscript". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 830–833. JSTOR 25189734.

- ↑ Hartmann, Jens-Uwe; Jens-Uwe Hartmann. "Buddhist Sanskrit Texts from Northern Turkestan and their relation to the Chinese Tripitaka". Collection of Essays 1993 : Buddhism across boundaries : Chinese Buddhism and the Western regions. p. 108. ISBN 9575438604.

- 1 2 3 Wujastyk, Dominik (1998). "Chapter 4: The Uses of Garlic (from the Bower Manuscript)". The Roots of Āyurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings. Penguin Books India. pp. 195–206. ISBN 978-0-14-043680-8.

- ↑ G. J. Meulenbeld, A History of Indian Medical Literature (1999–2002), vol. IIa, pp. 5

- ↑ G. J. Meulenbeld, A History of Indian Medical Literature (1999–2002), vol. IIa, pp. 6

- 1 2 G. J. Meulenbeld, A History of Indian Medical Literature (1999–2002), vol. IIa, pp. 8

- ↑ G. J. Meulenbeld, A History of Indian Medical Literature (1999–2002), vol. IIa, pp. 9

Further reading

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan. Indian Palaeography. (2nd edition New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1986).

- Peter Hopkirk, Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1980) ISBN 0-87023-435-8

- A. F. Rudolf Hoernle, The Bower manuscript; facsimile leaves, Nagari transcript, romanised transliteration and English translation with notes (Calcutta: Supt., Govt. Print., India, 1908-1912. reprinted New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 1987; archive.org edition)

- Sander, Lore, "Origin and date of the Bower Manuscript, a new approach" in M. Yaldiz and W. Lobo (eds.), Investigating the Indian Arts (Berlin: Museum Fuer Indische Kunst, 1987).

- Sims-Williams, Ursula, Rudolph Hoernle and Sir Aurel Stein.