Bookwheel

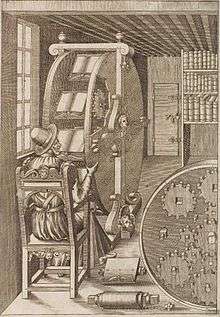

The bookwheel (also written book wheel and sometimes called a reading wheel) is a type of rotating bookcase designed to allow one person to read a variety of heavy books in one location with ease. The books are rotated vertically similar to the motion of a water wheel, as opposed to rotating on a flat table surface. The design for the bookwheel originally appeared in a 16th-century illustration by Agostino Ramelli, at a time when large books posed practical problems for readers. Ramelli's design influenced other engineers and, though now obsolete, inspires modern artists and historians.

History and design

The bookwheel, in its most commonly seen form, was invented by Italian military engineer Agostino Ramelli in 1588, presented as one of the 195 designs in Le diverse et artificiose machine del Capitano Agostino Ramelli (The various and ingenious machines of Captain Agostino Ramelli).[1] To ensure that the books remained at a constant angle, Ramelli incorporated an epicyclic gearing arrangement, a complex device that had only previously been used in astronomical clocks. Ramelli's design is unnecessarily elaborate, as he likely understood that gravity could have worked just as effectively (as it does with a Ferris wheel, invented centuries later), but the gearing system allowed him to display his mathematical prowess.[2] While other people would go on to build bookwheels based on Ramelli's design, Ramelli did not in fact ever construct his own.[3]

To what extent bookwheels were appreciated for their convenience versus their aesthetic qualities remains a matter of speculation according to modern American engineer Henry Petroski.[4] Ramelli himself described the bookwheel as a "beautiful and ingenious machine, very useful and convenient for anybody who takes pleasure in study, especially for those who are indisposed and tormented by gout."[5] Ramelli's reference to gout, a condition that impairs mobility, demonstrates the appeal of a device that allows access to several books while seated. However, Petroski notes that Ramelli's illustration lacks space for writing and other scholarly work, and that the "fanciful wheel" may not have been appropriate for any activity beyond reading.[4]

While the design of the bookwheel is commonly credited to Ramelli, some historians dispute that he was the first to invent such a device. Joseph Needham, a historian of Chinese technology, stated that revolving bookcases, though not vertically oriented, had their origins in China "perhaps a thousand years before Ramelli's design was taken there."[4]

Influence and legacy

The bookwheel was an early attempt to solve the problem of managing increasingly numerous printed works, which were typically large and heavy in Ramelli's time.[3] It has been called one of the earliest "information retrieval" devices,[6] and has been considered a precursor to modern technologies, such as hypertext and e-readers, that allow readers to store and cross-reference large amounts of information.[3] Other inventors, such as French inventor Nicolas Grollier de Servière (1596–1689), proposed their own variations on Ramelli's design.

Of the dozens of bookwheels built in the 17th and 18th centuries, 14 are extant: in Ghent, Hamburg, Klosterneuburg, Krakau, Lambach, Leiden, Naples (2), Paris, Prague (2), Puebla City, Wernigerode and in Wolfenbüttel.[7]

In contemporary times, the bookwheel is valued for its historical importance, decorative appeal, and symbolic significance. Ramelli's design has been recreated by artists such as Daniel Libeskind,[8] and inspired the name of the Smithsonian Library's blog "Turning the Book Wheel".[9]

Publications (selection)

- John Considine: 'The Ramellian Bookwheel'. In: Erudition and the Republic of Letters, 2016, 1: 4, 381–411

- E. Hanebutt-Benz: Die Kunst des Lesens. Lesemöbel und Leseverhalten vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. Frankfurt a. M., Museum für Kunsthandwerk, 1985. ISBN 3-88270-026-2

- M. Boghardt: 'Das Wolfenbuetteler Bücherrad'. In: Museum, April 1978, 58-60.

- Martha Teach Gnudi & Eugene S. Ferguson: Ramelli's ingenious machines. The various and ingenious machines of Agostino Ramelli (1588). Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976. ISBN 0-85967-247-6 (Repr. 1987 & 1994)

- Bert S. Hall: 'A revolving bookcase by Agostino Ramelli'. In: Technology and culture, 11 (1970), 389-400.

- M. von Katte: 'Herzog August und die Kataloge seiner Bibliothek In: Wolfenbuetteler Beiträge, 1 (1972), 174-182.

- A.G. Keller: A theatre of machines. London, Chapman and Hall, 1964.

- John Willis Clark: The care of books. An essay on the development of libraries and their fittings, from the earliest times to the end of the eighteenth century. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1901. [Repr. Cambridge 2009: ISBN 9781108005081]

- Agostino Ramelli: Le diverse et artificiose machine. Composte in lingua Italiana et Francese. Paris, 1588 (Repr.: Franborough, Hants, 1970) Google Books

References

- ↑ Brashear, Ronald. "Ramelli's Machines: Original drawings of the 16th century machines". Smithsonian Libraries.

- ↑ Rybczynski, Witold. One Good Turn: A Natural History of the Screwdriver and the Screw. Scribner, 2000.

- 1 2 3 Garber, Megan. "Behold, the Kindle of the 16th Century". The Atlantic. Published 27 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 Petroski, Henry. The Book on the Book Shelf. Knopf, 1999.

- ↑ Ramelli, Agostino. Le diverse et artificiose machine. 1588. Quoted in Rybczynski, Witold. One Good Turn: A Natural History of the Screwdriver and the Screw. Scribner, 2000.

- ↑ Norman, Jeremy. "Renaissance Information Retrieval Device". HistoryofInformation.com.

- ↑ John Considine: 'The Ramellian Bookwheel'. In: Erudition and the Republic of Letters, 2016, 1: 4, 408-409

- ↑ Allen, Greg. "On The Making Of The Lost Biennale Machines Of Daniel Libeskind". Greg.org.

- ↑ Blog post. Smithsonian Library.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bookwheel. |

- "Ramelli's Bookwheel", history and commentary from New York University's Department of Media, Culture, and Communication

- drifts through debris, an art installation inspired by Ramelli's design