Bobo doll experiment

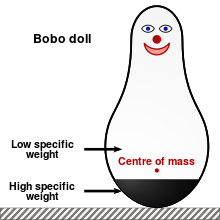

The Bobo doll experiment was the collective name for the experiments conducted by Albert Bandura in 1961 and 1963 when he studied children's behavior after watching an adult model act aggressively towards a Bobo doll, a toy that gets up by itself to a standing or upright position after it has been knocked down. There are different variations of the experiment. The most notable experiment measured the children's behavior after seeing the model get rewarded, get punished, or experience no consequence for abusing the Bobo doll. The experiments are empirical approaches to test Bandura's social learning theory. The social learning theory claims that people learn through observing, imitating, and modeling. It shows that people learn not only by being rewarded or punished (behaviorism), but they can also learn from watching somebody else being rewarded or punished (observational learning). These experiments are important because they sparked many more studies on the effects of observational learning. The new data from the studies has practical implications, for example by providing evidence of how children can be influenced by watching violent media.[1]

Experiment in 1961

Method

The participants in this experiment were 36 boys and 36 girls from the Stanford University nursery school, all between the ages of 37 months and 69 months with a mean age of 52 months (here and following, Bandura, Ross & Ross 1961). The children were organized into 4 groups and a control group. The 4 groups exposed to the aggressive model and non-aggressive model belonged to the experimental group. 24 children were exposed to an aggressive model and 24 children were exposed to a non-aggressive model. The two groups were then divided into males and females, which ensured that half of the children were exposed to models of their own sex and the other half were exposed to models of the opposite sex. The remaining 24 children were part of a control group.

For the experiment, each child was exposed to the scenario individually, so as not to be influenced or distracted by classmates. The first part of the experiment involved bringing a child and the adult model into a playroom. In the playroom, the child was seated in one corner filled with highly appealing activities such as stickers and stamps. The adult model was seated in another corner containing a toy set, a mallet, and an inflatable Bobo doll. Before leaving the room, the experimenter explained to the child that the toys in the adult corner were only for the adult to play with.

During the aggressive model scenario, the adult would begin by playing with the toys for approximately one minute. After this time the adult would start to show aggression towards the Bobo doll. Examples of this included hitting/punching the Bobo doll and using the toy mallet to hit the Bobo doll in the face. The aggressive model would also verbally assault the Bobo doll yelling "Sock him," "Hit him down," "Kick him," "Throw him in the air," or "Pow". After a period of about 10 minutes, the experimenter came back into the room, dismissed the adult model, and took the child into another playroom. The non-aggressive adult model simply played with the other toys for the entire 10-minute period. In this situation, the Bobo doll was completely ignored by the model, then the child was taken out of the room.

The next stage of the experiment, took place with the child and experimenter in another room filled with interesting toys such as trucks, dolls, and a spinning top. The child was invited to play with them. After about 2 minutes the experimenter decides that the child is no longer allowed to play with the toys, explaining that she is reserving those toys for the other children. This was done to build up frustration in the child. The experimenter said that the child could instead play with the toys in the experimental room (this included both aggressive and non-aggressive toys). In the experimental room the child was allowed to play for the duration of 20 minutes while the experimenter evaluated the child's play.

The first measure recorded was based on physical aggression such as punching, kicking, sitting on the Bobo doll, hitting it with a mallet, and tossing it around the room. Verbal aggression was the second measure recorded. The judges counted each time the children imitated the aggressive adult model and recorded their results. The third measure was the number of times the mallet was used to display other forms of aggression than hitting the doll. The final measure included modes of aggression shown by the child that were not direct imitation of the role-model's behavior.[2]

Results

Bandura found that the children exposed to the aggressive model were more likely to act in physically aggressive ways than those who were not exposed to the aggressive model. For those children exposed to the aggressive model, the number of imitative physical aggressions exhibited by the boys was 38.2 and 12.7 for the girls.[3] The results concerning gender differences strongly supported Bandura's prediction that children are more influenced by same-sex models. Results also showed that boys exhibited more aggression when exposed to aggressive male models than boys exposed to aggressive female models. When exposed to aggressive male models, the number of aggressive instances exhibited by boys averaged 104 compared to 48.4 aggressive instances exhibited by boys who were exposed to aggressive female models. While the results for the girls show similar findings, the results were less drastic. When exposed to aggressive female models, the number of aggressive instances exhibited by girls averaged 57.7 compared to 36.3 aggressive instances exhibited by girls who were exposed to aggressive male models.

Bandura also found that the children exposed to the aggressive model were more likely to act in verbally aggressive ways than those who were not exposed to the aggressive model. The number of imitative verbal aggressions exhibited by the boys was 17 times and 15.7 times by the girls.[3] In addition, the results indicated that the boys and girls who observed the non-aggressive model exhibited far less non-imitative mallet aggression than in the control group, which had no model. Lastly, the evidence strongly supports that males tend to be more aggressive than females. When all instances of aggression are tallied, males exhibited 270 aggressive instances compared to 128 aggressive instances exhibited by females.[4]

Experiments in 1963

Differences between learning and performing

Albert Bandura followed up his 1961 study a few years later with another that again tested differences in children's learning/behavior or actual performance after seeing a model being rewarded, punished, or experiencing no consequences for aggressive behavior towards a Bobo doll (here and following, Bandura, Ross & Ross 1963) .

The procedure of the experiment was very similar to the one conducted in 1961. Children between the ages of 2.5 to 6 years watched a film of a mediated model punching and screaming aggressively at a Bobo doll. Depending on the experimental group, the film ended with a scene in which the model was rewarded with candies or punished with the warning, "Don't do it again". In the neutral condition the film ended right after the aggression scene toward the Bobo doll. Regardless of the experimental group the child was in, after watching the film the child stayed in a room with many toys and a Bobo doll. The experimenter found that the children often showed less similar behavior toward the model when they were shown the clip that ended with the punishment scene as compared to the other conditions. Also, boys showed more imitative aggression than girls toward the Bobo doll. That is the measure of the performance and it supports the results of the experiments in 1961.

Next, the experimenter asked the children to demonstrate what they had seen in the film. The experimenter did not find differences in the children's demonstrated behavior based on which of the three films the child watched. The results of the experiment shows that rewards or punishment don't influence learning or remembering information, they just influence if the behavior is performed or not. The differences between girls and boys imitating behavior got smaller.[5]

Are children influenced by film-mediated aggressive models?

For many years, media violence has created many discussions concerning the influence over children and their aggressive behavior. In the 1963 study, Albert Bandura used children between the ages 3 and 6 to test the extent to which film-mediated aggressive models influenced imitative behavior.

For the experiment, 32 girls and 32 boys were divided into 3 groups and 1 control group. Group 1 watched a live model become aggressive towards the Bobo doll. Group 2 watched a film version of the human model become aggressive to the Bobo doll, and group 3 watched a cartoon version of a cat become aggressive towards the Bobo doll. Each child watched the aggressive acts individually. Following the exposure to the models all four groups of children were then individually placed in a room with an experimenter where they were exposed to a mildly frustrating situation to elicit aggression. Next the children were allowed to play freely in an adjoining room, which was full of toys, including the Bobo doll and the "weapons" that were used by the models. The researchers observed the children and noted any interaction with the Bobo doll.

Results showed that the children who had been exposed to the aggressive behavior, whether real-life, on film or cartoon, exhibited nearly twice as much aggressive behavior as the control group. It was also found that boys exhibited more overall aggression than girls. The results of this experiment have contributed to ongoing debates on media influences.

Theories supporting media effects

Two major theories that add to these ongoing debates on media influences are the General Aggression Model (GAM) and the effects of cultivation. Both of these theories explain the development of aggressive behavior and knowledge resulting from media's effect on children.

GAM specifically focuses on how we develop aggressive attitudes from exposure to violent media depictions and how it relates to aggressive behavior. Violent video games have become prevalent in today's society, which is another example of how exposure to violence can affect people's thoughts and actions. According to McGloin, Farrar & Fishlock (2015), "Triple whammy!", using a realistic gun controller correlated with double or nearly double that of most other effect sizes reported in meta-analytic work exploring the link between violent games and cognitive aggression. Overall, we gain aggressive knowledge when exposed to realistic violent media, therefore, behaving more aggressively through actions and words.

The "Cultivation Theory" argues that the more a child engages in media, the more they will be affected by it. Therefore, the more violent content the child is engaging in, the larger the impact it will have on them. We live in a society that is extremely technologically advanced. Children have the opportunity to observe violent images and media through TV, film, online media, and video games. For example, "Mean World Syndrome" discusses how news channels are only showing the negative things that are happening in the world. This skews our minds to believe that the world is a more dangerous place because we are only seeing what the media shows us.

The Bobo Doll experiment is supported by both the GAM and the Cultivation Theory. The conclusion of this experiment supports the social learning theory, that when one observes another's actions (the aggression model) they tend to behave in a similar way (an aggressive manner). In modern society, children observe and learn from the media, even when fictional. A child is more likely to replicate and learn from the character they see on screen when they identify with their personality traits (copycat violence) and if that character receives punishment or not.

Related experiments

Further 'doll' experiments

Due to numerous criticisms, Bandura replaced the 'Bobo doll' with a live clown. The young woman beat up a live clown in the video shown to preschool children and in turn when the children were led into another room where they found a live clown, they imitated the action in the video they had just watched.[6][7]

Other relevant experiments

The following a further set of experiments relevant to observational learning and social learning theory:

- 1. In Stein & Friedrich (1972), The "Mister Rogers" study. Procedure: A group of preschoolers watched Mister Rogers every weekday for four consecutive weeks. Result: The children showed higher levels of task persistence compared to others who saw neutral or aggressive programs. There were increases in cooperation and verbalization of feelings in children from low socioeconomic levels.[8]

- 2. Loye, Gorney & Steele (1977) conducted an Experiment using 183 married males aged between 20 and 70 years old. Procedure: The participants were to watch one of five TV programs for 20 hours over a period of one week while their wives secretly observed and recorded their behavior. Result: Participants of violent programs showed significant increase in aggressive moods and "hurtful behavior" while participants who viewed pro-social programs were more passive and demonstrated a significant increase of "emotional arousal".

- 3. Black & Bevan (1992) had movie-goers fill out an aggression questionnaire before and after watching a movie. Procedure: Subjects were randomly selected as they went to view either a violent or a romantic film. They were asked to fill out pretest and posttest questionnaires on their emotional state. Result: Those who watched violent films were already aggressive before viewing the film but it was aggravated after the viewing while there was no change in those who viewed romantic films.

- 4. Anderson & Dill (2000) randomly assigned college students to play two games; Wolfenstein (a science fiction first-person shooter game) and Tetris. This study has sometimes been criticized for using poorly validated aggression measures, and exaggerating the consistency of its findings (Ferguson, 2009).

- 5. Bartholow & Anderson (2002) examined how playing violent video games affect levels of aggression in a laboratory. Procedure: A total of 22 men and 21 women were randomly assigned to play either a violent or non-violent video game for ten minutes. Then competed in a reaction time task. Punishment level set by opponents measured aggression. Results: The results supported the researchers hypothesis that playing the violent video game would result in more aggression than the non-violent game. In addition, results also pointed to a potential difference in aggressive style between men and women.

Synthesis

These experiments relate empirically to Bandura's social learning theory. This social science theory suggests that people learn through observing, imitating, and modeling; moreover, it specifically suggests that people learn not only by being rewarded or punished (as suggested by theories in behaviorism), but also by watching others being rewarded or punished (observational learning). The experiments are important because they sparked much further study related to observational learning. As well, the data offered further practical working hypotheses, e.g., regarding how children might be influenced from watching violent media.

Criticisms

Claims regarding inherent bias

According to Hart & Kritsonis (2006), the original Bandura experiments were biased or otherwise flawed in ways that weakened their validity. The issues these researchers perceived were:?

- Selection bias. Bandura's subjects, all from the Stanford University nursery, were necessarily the children of Stanford students. Studying at a prestigious university like Stanford was a privilege reserved almost exclusively for whites in the 1960s; moreover, differences in economic status between white and black were vast at that time, so only whites in upper income brackets could send their children to a nursery. Thus, bias in the study subjects was present, with regard to race and socioeconomic background.

- Temporal sequence. The 1963 study used data on the "real life aggression and control group conditions" from the 1961 study;[9] hence, it is possible that the maturing of subjects and influences external to the studies, occurring over the period between the studies, could have contributed to the 1963 observations, results, and conclusions.

- Generalization of results. Even though Bandura and his colleague did not document subject ethnicity, they went on to make sweeping statements based on their results regarding aggression and violence in racial subgroups and communities with lower socioeconomic status.

Claims regarding motivation

Some scholars suggest the Bobo Doll studies are not studies of aggression at all, but rather that the children were motivated to imitate the adult in the belief the videos were instructions.[10][11] In other words, children were motivated by the desire to please adults or become adults rather than by genuine aggression. Furthermore, the same authors criticize the external validity of the study, noting that bobo dolls are designed to be hit.

Ethical claims

Challenges have been made regarding the ethics of the original studies. In a university-level introductory general psychology text, Bandura's study is branded as unethical and morally wrong, as the subjects were manipulated to respond in an aggressive manner.[12] They also state no surprise that long-term implications are apparent due to the methods imposed in this experiment as the subjects were taunted and were not allowed to play with the toys and thus incited agitation and dissatisfaction. Hence, they were trained to be aggressive.

Miscellaneous claims

Bar-on et al. (2001) described the frontal lobe of children under the age of 8 as underdeveloped, which contributed to their being unable to separate reality from fantasy; for instance, children up to the age of 12 may believe that "monsters" live in their closets or under the beds. They are also sometimes unable to distinguish dreams from reality.[13]

Furthermore, biological theorists argue that the social learning theory completely ignores individual's biological state by ignoring the uniqueness of an individual's DNA, brain development, and learning differences.[14]

See also

Further reading

- A. Bandura & R.H. Walters (1959). Adolescent Aggression, New York, NY, USA:Ronald Press.

- A. Bandura, (1962) Social Learning through Imitation, Lincoln, NE, USA:University of Nebraska Press.

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. (1963). Social learning and personality development. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston

- A. Bandura (1975) Social Learning & Personality Development, New York, NY, USA:Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- A. Bandura (1976) Social Learning Theory. New Jersey, USA: Prentice-Hall.

- A. Bandura (1986) Social Foundations of Thought and Action.

References

- ↑ McLeod, Saul. "Bobo Doll Experiment | Simply Psychology". Retrieved 2015-10-06.

- ↑ Bandura, Ross & Ross 1961

- 1 2 Hock 2009: 89

- ↑ Hock 2009: 90

- ↑ Bandura 1965

- ↑ Arvind Otta 2015

- ↑ Boeree 2006

- ↑ Yates 1999

- ↑ Hart & Kritsonis 2006

- ↑ Gauntlett 2005

- ↑ Ferguson 2010

- ↑ Wortman, Loftus & Weaver (1998),

- ↑ Sharon & Woolley 2004

- ↑ Isom 1998

- Anderson, Craig A.; Bushman, Brad J. (2001). "Effects of Violent Video Games on Aggressive Behavior, Aggressive Cognition, Aggressive Affect, Physiological Arousal, and Prosocial Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Scientific Literature" (PDF). Psychological Science. 12 (5): 353–359. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00366. JSTOR 40063648. PMID 11554666.

- Anderson, Craig A.; Dill, Karen E. (2000). "Video Games and Aggressive Thoughts, Feelings, and Behavior in the Laboratory and in Life" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 78 (4): 772–790. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.772. PMID 10794380.

- Bandura, A. (1965). "Influence of models' reinforcement contingencies on the acquisition of imitative responses". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1 (6): 589–595. doi:10.1037/h0022070.

- Bandura, A.; Ross, D.; Ross, S. A. (1961). "Transmission of aggression through the imitation of aggressive models". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 63 (3): 575–582. doi:10.1037/h0045925. PMID 13864605.

- Bandura, A.; Ross, D.; Ross, S. A. (1963). "Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 66 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1037/h0048687.

- Bartholow, Bruce D.; Anderson, Craig A. (2002). "Effects of Violent Video Games on Aggressive Behavior: Potential Sex Differences". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 38 (3): 283–290. doi:10.1006/jesp.2001.1502.

- Bar-on, M. E.; et al. (2001). "Media Violence: Report of the Committee on Public Education". Pediatrics. 108 (5): 1222–1226. doi:10.1542/peds.108.5.1222.

- Black, Stephen L.; Bevan, Susan (1992). "At the movies with Buss and Durkee: A natural experiment on film violence". Aggressive Behavior. 18 (1): 37–45. doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1992)18:1<37::aid-ab2480180105>3.0.co;2-3.

- Boeree, C. George (2006). "Personality Theories: Albert Bandura, 1925-present". Retrieved July 16, 2015. [Personal website of Prof. emeritus C.G. Boeree, Shippensburg University.]

- Ferguson, Christopher J. (2010). "Blazing Angels or Resident Evil? Can Violent Video Games Be a Force for Good?" (PDF). Review of General Psychology. 14 (2): 68–81. doi:10.1037/a0018941.

- Gauntlett, David (2005). Moving Experiences: Media Effects and Beyond (Volume 13 of Acamedia research monographs) (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN, USA: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0861966554. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- Hart, K.E.; Kritsonis, W.A. (2006). "Critical analysis of an original writing on social learning theory: Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models". National FORUM of Applied Educational Research Journal. 19 (3): 1–7. [Note, per the CV of Prof. Kritsonis, Prairie View A&M University (see ), this journal is a forum for publishing mentored doctoral student research.]

- Hock, Roger R. (2009). Forty Studies that Changed Psychology (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Isom, Margaret Delores (1998). "Albert Bandura: Social learning theory". Retrieved July 16, 2015. [Apparently from the discontinued website of Prof. M.D. Isom, formerly of the College of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Florida State University, original dead link, .]

- Loye, David; Gorney, Roderic; Steele, Gary (1977). "An Experimental Field Study". Journal of Communication. 27 (3): 206–216. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1977.tb02149.x.

- Murray, John P. (1995). "Children and Television Violence" (PDF). Kansas Journal of Law & Public Policy. 4 (3): 7–14. See also , both accessed 15 July 2015.

- Sharon, Tanya; Woolley, Jacqueline D. (2004). "Do monsters dream? Young children's understanding of the fantasy/reality distinction". British Journal of Development Psychology. 22 (2): 293–310. doi:10.1348/026151004323044627.

- Stein, Aletha H.; Friedrich, Lynette Kohn (1972). "Television Content and Young Children's Behavior". In J. P. Murray, E. A. Rubinstein and G. A. Comstock, eds., Television and Social Behavior, Volume 2: Television and Social Learning (pp. 202–317). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Wortman, Camille B.; Loftus, Elizabeth F.; Weaver, Charles A. (1998). Psychology (5th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Yates, Bradford L. "Modeling Strategies for Prosocial Television: A Review". AEJMC Southeast Colloquium, Lexington, KY, USA March 4–6, 1999. Retrieved July 16, 2015. [A paper presented by University of Florida doctoral student B.L. Yates to the Open Paper Competition of this regional Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication conference; faculty advisor unknown.]

- McGloin, Farrar & Fishlock (2015). "Triple whammy! Violent games and violent controllers". Journal of Communication.