Blanche Merrill

| Blanche Merrill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Blanche V. Dreyfoos July 23, 1883 Philadelphia |

| Died |

October 5, 1966 New York City |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | songwriter |

Blanche L. Merrill (born Blanche V. Dreyfoos July 23, 1883[1]—October 5, 1966) was a songwriter specializing in tailoring her characterizations to specific performers. She is most well-known for the songs she wrote for Fanny Brice.

Birthdate and education

Biographical information on Blanche Merrill is almost entirely absent. The only reference source that provides a tiny bit of biographical information is partially questionable.[2] This biography had to be constructed primarily from notices appearing in Variety and Billboard. These also must be read critically.

Blanche V. Dreyfoos was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Sigmund A. Dreyfoos (1855-January 12, 1899[3]), a bookkeeper,[4] and his wife, the former Elizabeth Murphy (approximately 1860-January 17, 1921.[3][5]) Although most sources are in agreement with the date of Blanche's birth (July 23), many provide conflicting evidence with regard to the year.

- The 1892 New York State census dated February 16, 1892, indicated that Blanche was 8 years old, making her born in 1883;[6]

- In the 1920 U.S. Federal census, her age is listed as 25, making her born in 1895;[7]

- According to the ASCAP Biographical Dictionary (based on her membership form filled when she became a member in 1936), she was born July 23, 1895.[2] The ASCAP source was used by the Library of Congress in establishing her date of birth.

- According to the 1940 U.S. Census she was born in 1900.[8]

- According to the Social Security Death Index, she was born July 22, 1883.[1]

Evidence leans toward 1883 as the correct year of her birth, particularly in light of her educational pursuits.

Her siblings were Nellie (born approximately 1879), Theresa (sometimes called Tessie, born approximately 1890[6]), Clara (sometimes spelled Claire, born February 15, 1881[9] ), and W. Wallace (born approximately 1888). Though census records indicate all the children were born in Philadelphia except W. Wallace; by the time of the New York State census of 1892, the family had relocated to Queens.[6] On January 21, 1899, Sigmund died in Brooklyn, age 43.[10] By 1900, a year after Sigmund's death, the family was living with the family of Elizabeth's sister at 147 5th Street in College Point, Queens.[11]

The details of her education are also problematic. In the 1917 interview Merrill claimed to have received a Bachelor of Arts degree from Columbia University, after which she took a city examination and received her license to teach "five years" prior to the interview.[12] However, in another profile published later that year, the unnamed author describes Merrill as having attended Barnard College.[13] If she was born in 1895, it is improbable that she would have graduated college and achieved teacher training by 1912 when she would have been 17. Although her college education remains mysterious, in 1906 she apparently passed her teacher training and was assigned to teach at Public School 84 in Queens.[14][15] Apparently she maintained this job until 1915 when she requested a sabbatical and apparently did not return.[16]

Career

Although Merrill claimed to have begun her theatrical career by sending an unsolicited song to Eva Tanguay, her interest in theater predates that event. In a 1917 interview Merrill described attending theater with her mother while in high school. "I never missed a Saturday matinee" she confessed.[12] A 1906 review of a production of The Jolly Bachelors put on by St. Mary's Catholic Club in Brooklyn is probably one of the earliest mentions of Merrill (still under her birth surname) in print. A reviewer for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported: "There were many musical numbers. Charles Bill, William Morrison and Blanche V. Dreyfoos managed to take one step higher in the art with which they have been so generously endowed." (Blanche's sister Clara Dreyfoos played the small role of Constance.) [17]

1910

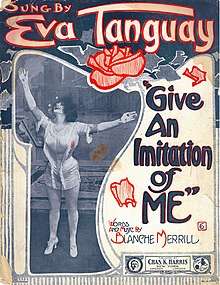

In 1910 she saw Eva Tanguay in a vaudeville performance.[18][12] She was so taken with the performance that she wrote her first song, "Give an Imitation of Me," and then filed it away. A friend convinced her to send it to Tanguay for her consideration. Tanguay liked it accepted it, leading Merrill to write an additional four songs for Tanguay. Although she didn't accept remuneration for her first effort, that changed when songwriter and music publisher Charles K. Harris signed Merrill to a contract and published her songs.[19] Among those songs was "Egotistical Eva" which Tanguay used to open her appearances for the 1910–11 season.[20] With her first publication, virtually all professional mentions refer to her as Blanche Merrill.

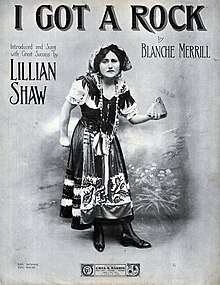

Soon thereafter, Harris published Merrill's "I Got a Rock." Written for Lillian Shaw, it is a song in a faux-Italian accent about an Italian woman angry at her cheating husband.[21] Aside from Fanny Brice and based on frequency of new material, Shaw is probably the performer for whom Merrill wrote the most material.

1912

A 1912 advertisement in Variety tells readers to "watch for new ideas in song form by Blanche Merrill and Leo Edwards."[22] Clearly Merrill was seeking clients. Her song "Bring Back My Bonnie To Me" was apparently a success not because of one performer, but through its dissemination by many performers. Among those who sang it were Helen Vincent,[23] the team of Gordon and Camber (in Portland, Maine),[24] and Reine Davies in Chicago.[25]

A young Mae West was just starting out in vaudeville. In finding her métier, she based much of her material on that of Eva Tanguay. Like Tanguay, she commissioned Merrill to write a song, "I Want to Dance, Dance, Dance."[26] West would approach Merrill again in 1916, wanting to do an act as a male impersonator and under a different name.[27]

The Trained Nurses, a vaudeville act written by and featuring Gladys Clark and Henry Bergman, was produced by Jesse L. Lasky at the Colonial Theatre in New York City on September 16, 1912. The plot involved a young man checking into a hospital with a nurse assisting him. He repeatedly asks her to marry him to which she finally consents. The act had four songs, three of which had lyrics by Merrill and music by Leo Edwards. The songs were "Humpty Dumpty," "I Can't Be True To One Little Girl When Another Little Girl Comes 'Round," "We've Had a Lovely Time, So Long, Good Bye" and Irving Berlin's "If You Don't Want Me."[28] One of the reviews foreshadow the distinctive nature of Merrill's lyrics. The reviewer wrote "The numbers written by Leo Edwards and Blanche Merrill are distinctly good for this kind of vaudeville."[29] Another critic in Billboard remarked on the song "We've Had a Lovely Time, So Long, Good Bye" "...a little song out of the ordinary. Miss Merrill's metrical flashes show some claim to originality, and admit of swinging, lilting music."[30] In Chicago, an unnamed critic wrote that the show "smoldered without breaking into flames of grandeur or impressiveness" and that "The music and lyrics of Leo Edwards and Blanche Merrill are pleasing, but nothing in the repertoire will have much of a vogue."[31] The act's success appears to have prompted Lasky to consider a new edition for the following year (the new version does not appear to have materialized).[32]

1913-1914

By 1913, Merrill was being noticed. "Several music publishing firms have been after the services of Blanche Merrill...who has gained a big reputation for her age within the past couple of years." Her work for Tanguay and Shaw as well as The Trained Nurses attracted "considerable attention from the profession to her jingling lyrics and ofttime melodies."[33] She eventually signed with the publishing triumvirate of Waterson, Berlin & Snyder, Inc.. This gave her the opportunity to collaborate with Irving Berlin. The single result of their collaboration was "Jake, the Yiddisher Ball Player," which was announced as "a hit" in Variety.[34] Thirty years later, critic Joe Laurie Jr. admitted "It never reached first base."[35]

L. Wolfe Gilbert, a notable lyricist, maintained a column in Billboard in which he remarked on popular songs of the day. Towards the end of 1914 he published a small complimentary notice in Billboard: "There's a little lady in the song game now who is making many of our men writers look to their laurels."[36] By the end of 1914 Merrill's clients included Eva Tanguay, Gus Edwards' Song Revue, Lillian Shaw, and Gertrude Barnes "among others."[37]

1915

The beginning of 1915 saw Eva Tanguay making her first appearance at The Palace in New York. The critic wrote: "Miss Tanguay has the best collection of numbers, lyrically, she has yet sung at one time. The songs are well written with telling points, as if, as reports say, Blanche Merrill wrote Miss Tanguay's new numbers, Miss Merrill is shooting ahead rapidly as a song writer. The numbers are, of course, greatly aided by Miss Tanguay's sprightliness and knowledge of delivering songs built to fit her style."[38]

Although giving the impression of a book-based musical, Maid in America, which opened at the Winter Garden Theatre on February 18, 1915, was essentially a vaudeville revue.[39] Among the many interpolations was "Whistle and I'll Come To You" by Merrill and Leo Edwards whose performance by Nora Bayes did not go unnoticed.[40][41] Another one of Merrill's and Edward's songs, "Here's to You, My Sparkling Wine," made its way into the musical The Blue Paradise which opened at the Casino Theatre on August 5, 1915 and then toured.[42][43]

Merrill wrote the song "Broadway Sam" for comic Willie Howard who performed it in The Passing Show of 1915. Although the reviewer, Sime Silverman (the founder of Variety), omitted Merrill's name, he mentioned the song twice, noting that it was a vehicle for Howard's affinity for imitations.[44][45]

Merrill supposedly appeared on stage playing a violin in Seven Colonial Belles. The critic said "Blanche Merrill, a lively violiniste with luminous optics, seems held down to some extent."[46] But Barbara Wallace Grossman (Fanny Brice's biographer) strongly doubted that Merrill appeared on stage, and presumed the critic made a mistake in his attributions.

Beginning in mid-1915, there are notices of Merrill composing not just songs but writing vaudeville acts. Under the byline "Tommy's Tattles" (the equivalent of a gossip column), Thomas J. Gray reported: "Blanche Merrill, who has steadily come forward until she is one of the recognized work writers of the profession, a position gained by her through original and fresh ideas for vaudeville, has been commissioned already to turn out several acts for next season. Among those Miss Merrill will write turns for are Fannie Brice, Lillian Shaw, Harry Hines, Maurice Burkhardt, Irene Martin and Skeets Gallagher, Mary Gray, and Helen De Forest and Geo. Kraft."[47] A Variety notice near the end of October 1915 indicates an act, "The Musical Devil" featuring a performer "Yvette" was written by Merrill.[48]

One of the first of Merrill's vaudeville acts to be reviewed was The Burglar, a 15-minute skit written for Maurice Burkhardt. Seen at the Prospect Theatre in Brooklyn the end of October 1915, the unnamed Variety critic wrote positively and prominently of Merrill's contribution.[49] Advertising for the act also included Merrill's name.[50]

Fanny Brice, 1915-1925

In 1915 Fanny Brice was already a noted comedienne. The public came to admire her not for any particular role she played, but for her fine comic sense honed through many years of playing vaudeville and revues. "In Brice's best stage work...the emphasis was on the character and her incongruous behavior. Brice's antics always pointed to the discrepancy between the character's perception of herself and the way she appeared to others. The audience's awareness of that disparity made the character seem ridiculous, and Brice's hilarious actions always heightened the comic effect."[51]

By 1915 Merrill had established a strong reputation as a songwriter who catered to the individual characteristics of specific performers, women in particular.[52] In July 1915 Brice began to work with Merrill. Grossman calls Brice's meeting with Merrill the "turning point in [Brice's] career and the beginning of a productive professional relationship. During their association, Merrill created some of Brice's most distinctive material and freed her from the problem that had always plagued her: finding songs that really suited her."[52]

The first results of their collaboration resulted in Brice's act opening on September 6, 1915 at The Palace.[52] After touring with and refining the material, Brice returned to The Palace in February 1916. The act had four songs, the latter three of which had lyrics by Merrill: "If We Could Only Take Their Word," "The Yiddish Bride" (which critic and Variety founder Sime Silverman called "a gem"), and "Becky Is Back in the Ballet." After one performance, Sime recounted that the audience applauded so much that Brice came out in front of the curtain and announced "I ain't got no more material. What do you want of my young Jewish life?"[53]

Brice's next major appearance was in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1916. Opening on June 12, 1916, among the songs Brice sang were two with lyrics by Merrill, "The Hat" and "The Dying Swan."[54][55] Subsequently Brice interpolated two additional songs by Merrill which had been a success in her act, "Becky is Back in the Ballet" and "If We Could Only Take Their Word." In an unusual full-page advertisement in Variety, Merrill announced that her name was omitted from the program for the Ziegfeld Follies of 1916 and that she was the lyricist and composer for two of Brice's hits, "Becky is Back in the Ballet" and "If We Could Only Take Their Word."[56]

The Ziegfeld Follies of 1917 had Brice in only two numbers, both by Merrill. One of them was "Egyptian," a song about a Jewish girl who yearns to be an Egyptian dancer, "with Miss Brice adding to the humor of the lyrics with her arm and body movements."[57] Grossman quotes a Variety review, saying it was a "personal triumph" for Brice and that she was "the real riot of the evening."[58] According to Grossmann, the song "Egyptian" was "the type of material Brice did so well, in dialect about an inept dancer with satirical references" to Ruth St. Denis. It was about a Jewish girl who yearns to be an Egyptian dancer. "In addition to the bars where dance steps are indicated, the lyric suggest the kind of movement with which Brice liked to animate a song." Grossman remarked on the New York Times review that praised those performers who didn't rely on the show's script but brought in and performed their own material....including "the droll Fanny Brice whose sense of travesty amounts to genius."[58]

Why Worry? was a play with music and was Brice's only attempt to play a serious role on Broadway. During its tour prior to opening on Broadway, the play closed temporarily due to illness of one of the performers. Initial reports was that the play lacked class. When it re-opened in Atlantic City, New Jersey for the continuation of its pre-Broadway run, it included two songs written by Merrill, one called "The Yiddish Indian."[59] After a troubled beginning, Why Worry? opened at the Harris Theatre on Broadway on August 23, 1918.[60] Despite closing only three weeks later, Brice knew she had valuable material. By December 1918 she was appearing in Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic where she performed three songs, "The Vampire," a travesty number as a French soubrette and "an Indian song" which, based on quotations in a review, is clearly "I'm an Indian." Critic Sime described this last song as being written especially for her because the line "He calls me eagle because I have a beak" reflected on Brice's Jewish nose. Critic Sime noticed that Brice's superlative performance did not overshadow the lyricist: "Miss Brice contributes much to the delivery of these songs, but not as much as Miss Merrill with the idea first and the lyrics first and second."[61]

The characteristic humor mentioned by Grossman as being one of Brice's (and Merrill's) traits are very apparent in "I'm an Indian" which tries to portray a Jewish woman incongruously becoming the wife of a Native American. It is also an example of the clarity used by Merrill in her portrayal of characters.

VERSE

Look at me I'm what you call an Indian

That's something that I never was before.

But one day I met Big Chief Chickamahooga,

and right away he grabb'd me for a squaw.

He wrapp'd me up in blankets

Put feathers in my head

Between the blankets and the feathers

I feel just like a bed.

And now oi oi my people

How can I tell them how

Their little Rosie Rosenstein

Is a terrible Indian now.[62]

"I'm an Indian" was one of Brice's most enduring characterizations. She recorded it in 1921,[63] and the music was published in 1922. Brice performed it in her 1928 film My Man[64] and Brice's performance of the song was briefly portrayed by cartoon character Betty Boop in the 1932 animated short Stopping the Show (the sequence was also used in the 1934 short Betty Boop's Rise to Fame). Finally, "I'm an Indian" is briefly viewed in a puppet rendition (by Lou Bunin) for Brice's final film appearance in the 1945 film Ziegfeld Follies.

Merrill wrote songs for Brice's appearances in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1920[65] as well as the Ziegfeld Follies of 1921.[66] In the latter revue, one critic wrote that Brice sang a "Scotch Lassie" song (undoubtedly "A Hieland Lassie"), "A comedy number without any great merit, but made into a hit by the way it was done."[67]

The following year Brice had an all-Merrill program[68] before working up an act called Around the World.[69] The idea behind the act was that Brice would portray people from different cultures. Variety reviewer Sime described the opening number as consisting of three different styles of lyrics, and unusually, the lyrics had Brice refer to Merrill. This is the song "Make 'Em Laugh". Longer than a typical song, it has Brice portraying herself travelling around New York City, going to the Belasco Theatre to the Music Box Theatre in search of the right kind of material to perform. Finally she resolves to find Merrill:

I pulled a nifty forward pass on them with one thing on my mind:

My authoress Blanche Merrill was all I wanted to find.[70]

The song describes Brice suggesting to Merrill a dramatic scene, or something operatic. Merrill responds with the refrain by saying that Brice's talents are in comedy and that she should "make 'em laugh."[70]

The next song was "A Scottish number with a Yiddish accent" (undoubtedly "A Hieland Lassie"), then a song sung by the lonely wife of a rich New Yorker, followed by a song sung by a lonely wife of a poor New Yorker. The scene switches to Wyoming for Indian number (undoubtedly "I'm an Indian"), then ancient Greece in a burlesque of the Spring Song (the song "Spring").[71] When she brought her act to The Palace, critic Sime mentioned that the Ziegfeld Follies and the Ziegfeld Frolics "...have made the Brice name known as covering a comedienne, no small portion of that distinction going to Miss Merrill, who understands Miss Brice so well and can so fit her personality and style that the best songs Fanny Brice has had and those she has now brought into vaudeville were written by that brilliant young woman."[69]

For her 1923 vaudeville act, Brice sang at least four songs, all with lyrics by Blanche Merrill: "Hocus Pocus," "My Bill," a ballad called "Breaking Home Ties" and a "new Spanish comedy song."[72]

Near the end of his career, songwriter Jack Yellen recalled Tin Pan Alley and that writers of special material sometimes got the better end of a deal. He mentioned Merrill, whom he called "an expert" who could command thousands of dollars for material, with Fanny Brice being one of her steady and smart customers.[73]

Apparently there was a break in the relationship between Brice and Merrill in 1924. Merrill published poem in Variety in 1924 that Brice was now a "Belasco star" and that Merrill was her "use-to-be writer." Grossman hypothesized that Brice felt Merrill couldn't do anything more for her career. After her marriage to Billy Rose, a songwriter, it's possible that he disallowed collaboration between Brice and Merrill because of professional jealousy. As related by a relative to Grossman, Merrill supposedly said of Rose: "Ugh! If you ever saw his fingernails—they were black!"[74]

Although they were no longer working together, in an extensive November 1925 interview with Brice, she had warm words for Merrill.[75]

1916

In reviewing Harry Rose's appearance at the Royal Theatre in April 1916, Variety reviewer Wynn begins with an unusually generous estimate of Merrill who authored Rose's act: "When a vaudeville author or authoress scores a half dozen big times "bull's eyes" in less than as many weeks, it's about time to deviate from the conventional method of review and spread a little credit in the proper direction. Blanche Merrill is the particular personage referred to, for Miss Merrill is wrecking the standing record for consistency and durability in producing vaudeville successes." After describing Rose's act, Wynn concludes: "As a first aid to capable acts, Blanche Merrill ranks second to none, and it is to be hoped vaudeville will do as much for her as she can do for vaudeville."[76]

A similar mention is found in a review of Dorothy Granville's "Types of Women." In her act she impersonated various types of women, including a cabaret girl, a shop girl, and an athlete among other types. The notice attributed the entire act to Merrill.[77] The advertisement for Granville's act had Merrill's name in larger type than similar advertisements for Tanguay or Burkhardt.[78]

Blanche Merrill and Max Hart agreed to co-produce for vaudeville. Al Wohlman will appear shortly in a new act by Merrill.[79] An advertisement for Tyler Brooke and Patsie De Forest has the line "exclusive material by Blanche Merrill."[80] A review indicates that their representative was Max Hart, apparently an outcome of Merrill's agreement with Hart.[81] Nearly two years later Hart himself would be in A Military Wedding, an act written for him by Merrill.[82]

On occasion a review indicated that Merrill supplied purely an act without any songs. Such is the case with Murry Livingston who was described as "in a new monolog by Blanche Merrill."[83]

Wynn reviewing Arthur Lipson, writes: "opening with an introductory prologue and proceeding through a German imitation to a corking good medley, describing in lyric form the construction of a modern song. It runs the gamut of melody from opera to ragtime with an interesting theme and a range in tone built expressly to exploit the vocal ability of the principal."[84]

Other Merrill clients and works from 1916 included Willie Weston in The Hunter,[85] Clara Morton in The Doll Shop (originally titled The Toy Shop)[86] in which Morton impersonated various dolls,[87] and Gertrude Barnes in an act featuring a vampire song called "The Temptation Girl."[88]

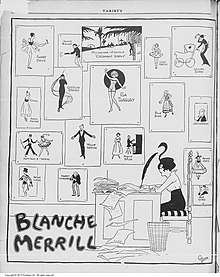

Merrill's talents had become so well known by the end of 1916 that Variety published a full-page caricature of Merrill writing for numerous vaudeville players who were clients: Fannie Brice, Maurice Burkhart, Clara Morton, Lillian Shaw, Dorothy Meuther, Gertrude Barnes, Eva Tanguay, Belle Baker, J.D. Chadwick, DeForest & Kearns, Willie Weston, Arnold & Taylor, Arthur Lipson, Maurey Livingston, as well as the Charles Dillingham's and Florenz Ziegfeld's "Cocoanut Grove" nightclub.[89]

Though the caricature included the Cocoanut Grove, Variety did not explain the connection until the venue opened at the beginning of January. As a way of capitalizing on the success of Ziegfeld's Midnight Frolic, a cabaret-style evening held on the roof of the New Amsterdam Theatre, Charles Dillingham and Florenz Ziegfeld opened the Cocoanut Grove on the roof of the Century Theatre. Blanche Merrill was announced as the Cocoanut Grove's official songwriter. The first show was announced as Eat and Grow Thin; by the time it opened on January 5, 1917, it was retitled as Dance and Grow Thin.[90][91] The music was by Irving Berlin and Merrill.[92] A review mentioned the highlights of the presentation, including Merrill's "Letter Boxes" (a set piece which had chorines costumed as letter boxes), a song "Cinderella Lost Her Slippers," and a "Birdie" song.[93]

1917

A brief 1917 profile of Merrill described her appearance as "businesslike" and clothed with "extreme smartness and sophistication."[18] That year she could command $20,000 for each song.[18][73]

A February 1917 advertisement in Variety announced Merrill's latest vaudeville skit, On the Scaffold. This skit was written for Roy Rice and Mary Werner and was done in blackface. Of particular note is the ad's warning: "This act, in its entirety, business, dialog, scenes and situations is wholly original in every way and has been filed with and is protected by 'Variety's' Protected Material Department."[94] Clearly the creators and performers were concerned about others unauthorized used of the material.

The skit involved a blackfaced window washer and his flirtations with a housekeeper who is a blackfaced woman inside an apartment. After songs and repartee, and worried that the head of the apartment may soon return, the woman climbs out of the window and lands on the scaffold. Much of the comedy derived from the physical actions that went along with the story. The first review of On the Scaffold was of its engagement at the Bushwick Theatre in Brooklyn. The reviewer praised Mary Werner for her comic abilities, and concluded "On the Scaffold is quite funny and wholly original act, sure fire for vaudeville as a laugh compeller, and good enough as a comedy scene for the best of the musical production."[95] Rice and Werner subsequently performed it at the Hippodrome Theatre in London in 1921,[96] and at the Palace in New York in 1922,[97] Apparently it was successful enough that the comic duo held on to this material for years. They were still performing it in 1930 with a "post-prohibition appendage."[98]

Advertisement for Ethel Arnold and Earl Taylor in a vaudeville act, Put Out by Blanche Merrill.[99] By the time it opened in April it was re-titled Dispossesed. The reviewer mentioned Merrill in the first line, calling it "a nice little two-act...the opening giving the couple a good entrance and this is carried forward with dialog and specially written numbers by Miss Merrill to a logcial conclusion.[100] A later review noted that Arnold performed "a very clever imitation of Miss Merrill, indicating the authoress must have rehearsed her carefully."[101]

Reviewer "Jolo" was disappointed at a vaudeville evening at the Royal Theatre, but singled out Belle Baker for her comedy, noting that the audience wanted more. He described her singing three "Yiddish" numbers, but criticized the choice of songs since two covered the same subject. The songs were "I'm a Baker" (the song a pun on the performer's surname), "When You and I Were Young, Abie," and "Nathan." The review concluded noting that the audience loved it so maybe her judgement is better than the reviewer's.[102]

Belle Baker closing act at the Riverside Theatre. She had several songs by Merrill "with lyrics that compel attention and laughs." The reviewer said Baker can be proud that, being the last act on the program, the audience was still enthusiastic.[103] A half-page advertisement in Variety displays prominently "with special song material by Blanche Merrill" directly under Baker's name.[104] Indeed, the reviewer, W.J.H., proclaimed "Belle Baker, in special songs by Blanche Merrill, stopped the show. There is no gainsaying the fact that this attractive little woman has New York all her own way when it comes to putting over songs. Her vivacity, her ginger and characterizations fitting separately to each effort is probably unsurpassed by any other singer today."[105]

In August 1917 Carrie Lillie appeared in the vaudeville act written by Merrill, In the Wilds. The review first remarks on Merrill's contribution: "An exceptional writer for vaudeville is that Blanche Merrill. No one understanding vaudeville can watch her output upon the stage without pondering. The material is always there in a Merrill act and if it doesn't get over, it's invariably the fault of the interpreters of it." After briefly covering Lillie's actions, the review returns to Merrill by way of the songs she provided. "The closing song was a 'Bluebird' number, with pretty and appropriate costuming. It's one of the best songs lyrically Miss Merrill has ever written. While this young girl writer as a rule appears to have no bent toward commercialism in her songs, which is as much to her credit artistically as it may be against her bank account, financially 'The Bluebird' number is quite apt to become a fair seller. The story of the song is attractive and while Miss Merrill gives no striking originality to her music, she generally hits upon some little catchy tune and is very close to the Harry Lauder scheme in this respect. For a personal preference Miss Merrill's own music as a rule for her own lyrics makes a better total than when she has a composer set the air to her words. It's quite safe to predict Blanche Merrill is going to be one of America's leading lyricist and she could easily be conceded that distinction now, for she is a girl with ideas, a really prolific original writer, with a fresh mind that should be kept fresh and it will continue to bear the same wholesome fruit it is now giving. The Blanche Merrill part of the Carrie Lillie act takes precedence over Miss Lillie, who, however, aptly put its over, and the combination of materials and artists composes one of the best single woman acts in vaudeville, for a high grade novelty clean and pleasing turn."[106]

Other performers and their acts in part or in whole written by Merrill during 1917 included Anna Ford and George Goodridge in You Can't Believe Them,[107] Grace Cameron returning in Dolly Dimples,[108] Mabel Hamilton (formerly of the duo Clark and Hamilton) in a solo act,[109][110] and Lillian Shaw, having the penultimate spot in vaudeville program at the Colonial Theatre. Her act was composed of dialect songs with a Jewish accent and closes with a baby carriage in hand and a song about marriage.[111] A brief notice on Merrill's and Leo Edwards's song "I'm From Chicago" in which the lyricist lauded the town "in a most forceful manner".[112]

Having written a variety of vaudeville acts, in October 1917 it was announced that Merrill was putting aside specialty work in order to write a play. She predicted it would take about three month's time. The noticed indicated that several managers had already expressed interest.[113] No play emerged; Merrill kept on contributing interpolations to various shows and revues.

At the end of 1917 Merrill put out full-page advertisements offering "Holiday greetings Blanche Merrill."[114][115]

1918

An anonymous 1918 article in Variety begins with mention of the song "Where Do They Get Those Guys?" being performed by Constance Farber as an interpolation in the musical Sinbad. The article continues however by talking of Merrill's desire for tighter control over her work. With the aid of her lawyer, Merrill was able to get a clause written into her contracts that restricted performance of her songs to the field to which they were conceived, whether vaudeville or musical comedy. Merrill was also able to obtain a restriction on performing rights, stipulating that a performer could not transfer performing rights to another performer. This restrictive clause was occasioned by an incident with Fanny Brice who paid Merrill $1,000 for two songs, but then gave the song "I Don't Know Whether To Do It or Not" to Lillian Shaw. Merrill was contemplating action against Brice, but either withdrew or the action was settled.[116][117]

Much of 1918 had Merrill writing for various performers.

- Lillian Shaw, returning after a two-year absence, played an act that included "a Hebrew comedy ballad about driving wolves from the door," the pun being her in-laws with the surname of Wolf. A reviewer wrote "The lyrics can not be described; but they never miss a tap. Blanche Merrill wrote them in her funniest and surest six-cylinder strain. Miss Shaw sang them for every fibre and spark that they provided."[118]

- An act written for Fay, Two Coleys and Fay (two of whom perform in blackface portraying a crow and blackbird).[119] One review noted that it needed more work but was destined for "the big time."[120]

- Ioleen Sheridan, appearing in her first vaudeville act since leaving burlesque.[121]

Among the most notable of performers to sing Merrill material during this time was probably Bert Williams, who sang "I Ain't Gwine Ter be no Fool There Was" by Merrill in Ziegfeld's Midnight Frolic.[122]

The onset of World War I led Merrill to write two works whose temperament were very different from each other. One was a popular song, "Boots, Boots, Boots." Written as a parody of Rudyard Kipling's poem Boots, it was first performed by the Howard Brothers at the Winter Garden Theatre in The Passing Show of 1918.[123]

The other work was a "Drum Number" apparently written for Sophie Tucker and never published. A serious recitation in rhyming verse with occasional accompaniment from a drum and tunes of the war (such as When Johnny Comes Marching Home), the Drum Number told of Johnnie, a little boy who received a present of a toy drum and fell in love with it, playing it all the time. Years later as an adult, he is drafted and goes to war. He survived but not without extreme trauma. The concluding paragraph begins by describing the effect of war on Johnnie: "But when his people saw him, with horror they were dumb / For Johnnie had come home again, but his tortured brain was numb." The remainder of the paragraph described how the shell-shocked Johnnie was unable to do anything but play the toy drum.[124]

1919

The first major controversy of Blanche Merrill's career occurred in 1919. As originally announced, Merrill was to write and compose all the musical numbers for the Ziegfeld Follies of 1919.[125] Subsequent notices indicated a division of responsibility. Merrill would write the first act,[126] Irving Berlin would write the second act,[127] and Gene Buck would write the third act.[128] The situation changed when Ziegfeld asked Merrill to allow composer Dave Stamper to rewrite the music for three of her songs. According to Variety, Merrill refused and withdrew from the project entirely, signing on with the Shubert Brothers to work on their upcoming show, Biff Boom Bang.[129] But according to Barbara Wallace Grossman, Merrill was fired.[130]

Though Biff Boom Bang did not materialize, Merrill, along with lyricist M.K. Jerome, contributed lyrics to three songs to the revue Shubert Gaities of 1919. (The songs were "Coat O' Mine," "Crazy Quilt," and "This is the Day."[131]) An advertisement for the Shubert Gaities of 1919 praises performer Ina Williams. Near the bottom of the full-page ad are the words "Thanks to Blanche Merrill who conceived the idea and wrote the 'Crazy Quilt' number." Notably, Merrill's name is printed in all capital letters that cover the width of the printed page.[132] Apparently the advertising did little to dispel the revue's reception. An unnamed Variety critic wrote "None of these lyrics are especially favored, though the lack of voices prevents their being understood to a large extent."[133] Writing in Billboard, critic Gordon Whyte tersely remarked that the show lacked comedy and a song hit.[134] A curious postscript appeared in the "Letters to the Editor" of Billboard. In it, the group known as the "Crazy Quilts" objected to the ad for the Shubert Gaities of 1919 claiming that they had written the "Crazy Quilt" song.[135]

A notice in a July 1919 issue of Variety stated that Merrill had signed a contract with Lee Shubert to produce a musical version of Clyde Fitch's play Girls. Although this was intended to be a vehicle for Nan Halperin, the notice warned that Halperin was known only from vaudeville and lacked theatrical experience.[136] When the musical opened on November 3, 1919 it was called The Little Blue Devil and neither Halperin nor Merrill were associated with it.[137] Merrill did write an act for Halperin which opened in the summer of 1920.[138]

The lack of writing the musical version of Girls might have been the cause of the dispute between Merrill and the Shubert Brothers.[130] Apparently that did not reduce Merrill's value. Variety reported that "Blanche Merrill Inc." increased its capital from $1,000 to $10,000.[139]

Among the performers and acts Merrill wrote in 1919:

- George Price did a recitative number with a handkerchief written by Merrill.[140]

- The play Come Along had a song by Merrill interpolated, "But You Can't Believe Them," performed by Allen Kearns and Patsie De Forest (the two had performed the song in vaudeville).[141]

- Katheryn Claire appeared with Joe Fields in a comedy sketch by Merrill.[142]

- Billy Shoehn's act had been totally rewritten by Merrill resulting in a smoother presentation.[143]

1920

Merrill contributed lyrics to the musical Page Mr. Cupid which had a book by Owen Davis, and music by Jean Schwartz, and was produced by the Shuberts. The show opened at the Shubert Crescent Theatre in Brooklyn on May 17, 1920.[144] A curious notice subsequently appeared in Variety stating that the Brooklyn opening of Page Mister Cupid was "the first time a show has been booked outside of Manhattan prior to its New York opening."[145] Perhaps the producers were hoping that the show would move to Broadway (it did not).

The fall of 1920 saw the continuation of the professional relationship between Merrill and Lillian Shaw when the latter appeared at the Palace in song scenes by Merrill. A reviewer wrote "Miss Shaw was literally a howling success as far as the audience was concerned. Her second number was slightly blue in spots, but when those particular spots arrived the Palace crowd shrieked their delight. There are some spots where the talk is a little broad, so broad it may be a question how they will take it away from Broadway, but Miss Shaw is sufficient [a] showwoman to know where and where not to use it."[146]

Some of the activities that occupied Merrill in 1920 were:

- Merrill wrote act for Gertrude Barnes containing four to five songs [147][148]

- Merrill writing and act called "The Man in the Moon."[148]

- Florence Tempest will appear in an act by Merill.[149][148]

- The Shuberts had optioned the play "A Weekend Marriage" (which closed in Atlantic City), hoping that Merrill would turn it into a musical.[150] Nothing appears to have come from these plans.

- In a dispatch dated April 7, Variety noted that Merrill was in Chicago for a week concerning "Shubert affairs." While there she spent time at the Woods and Garrick theatres which were home to "Monte Cristo Jr." and the touring production of the Shubert Gaities of 1919.[151]

- Theatrical producer Harry Frazee commissioned Merrill to produce musical versions of two of his plays, My Lady Friends and A Pair of Queens.[152] Neither of these commissioned appeared to have seen fruition. (My Lady Friends was eventually turned into the musical No, No, Nanette.)

1921

The lack of Merrill's activity from the end of 1920 last through the middle of 1921 was due to the illness and death of her mother, Elizabeth Dreyfoos, on January 18, 1921. According to the obituary, Merrill's mother, aged 58, a resident of Hunter's Point, Queens, had suffered from an attack of paralysis from which she never recovered.[153][154] Once Merrill returned to activity in the summer of 1921, a critic remarked on her absence and return, and wrote: "The stage needs writers of Merrill's calibre [sic], who pen freshly..." The critic noted that her latest efforts [the Greenwich Village Follies of 1921 and the vaudeville acts of Anna Chandler and Sidney Lanfield] were "extremely successful."[155]

Of Belle Baker's appearance at the Brighton Theatre in Brooklyn, Variety critic Jack Lait favorably commented on the opening song, "Welcome Stranger," written by Merrill. He said it was in Merrill's "best lyrical style...While subject to opinion as too personal, its lyric, however, appeals strongly to those not conversant with Miss Baker's domestic happiness, and so it gets to 'em both ways right at the start of the turn."[156]

The team of Ann Ford and George Goodridge sang Merrill's "You Can't Believe Them" which was well received.[157] Two weeks later at the Royal Theatre, a Variety critic wrote that the vaudeville act "owes much of its success to the clever song stories that the author has draped the turn on."[158] Their rendition of the song was still news weeks later in December.[159]

A notice in Billboard said that Merrill collaborated with John Murray Anderson on the Greenwich Village Follies of 1921, the third production in that series of revues.[160] But when the show opened on August 31, 1921, the only credit to Merrill was a single song, "Pavlowa."[161] Variety reviewer Jack Lait was kind to Merrill but not to the show, describing it as "devoid of wit and is smeary with smut." "Blanche Merrill gives it the only touch of brightness in idea that it has...Miss Merrill's witty lines stood forth like gems against the mud and muck which slopped over the rest of what script there was. Miss Merrill is naughty, too; but she is smart; she is wise; she is a satirist, not a dirty-story teller. If she had written the show, with that staging and those clothes and those settings around her brilliant ideas and brilliant expressions of those ideas, this would have been a great 'Follies.'"[162]

Formerly together, Anna Chandler and Sidney Lanfield (her former accompanist) were doing separate acts but on the same program, both acts written by Merrill. The Variety critic first described Lanfield's act in which he entered with a "clever" song about how his baby grand piano is his grand baby. Then a "Stop Look and listen" topical song along with a song about "Mr. Jazz and Mr. Opera" in which Lanfield acknowledged aspects of musical comedy tracing back to opera.[163] The critic then described Chandler's act, saying how she went into "her exclusive song cycle, each number a gem for which she owes Blanche Merrill considerable."[164] The critic enumerates Chandler's songs: "I've Dug All I Could, But See What I'm Getting," followed by a "dialect song" and a "Camile" song, then "A Dog's Tale of Love" a "Zulu Zo" song. "Each of the Merrill songs is a comedy gem, and Miss Chandler's ability to exact the most out of such ditties has long since been proven."

Other 1921 activities for Merrill included:

- Oddities of 1921 (Merrill was credited with writing the act but a critic found the act suffered after the first two scenes;[165]

- Sonia Meroff in a fourteen-minute act. Opening number something like "I'm Going To Build a Theatre of My Own." Second is a bride number. Then an "Italian blues" number. Concluding with a jazz song and an encore with a pop ballad.[166]

- An act for George Stone and Etta Pillard;[167][168]

- work on transitioning Eva Tanguay into a cabaret career. Included song by Merrill, "A Little Jazz Band of Our Own."[169]

- An act for Marie Russell[170]

1922

The rhymes that have been appearing at the head of Variety's show reviews are by Blanche Merill, although other names have been used. As in her songs, each poem sought to portray some performer. "Miss Merrill has hit off the style of those she composes for in a remarkable manner. It is something entirely new in rhyming, and especially as Miss merrill does it, waiting until the last moment." Several years ago Variety received anonymous critism in the style of verse, signed simply "Blanche." These were by Merrill. She continued supplying the verses while being a teacher in Long Island City. Where she then lived. "Probably one of the brightest minds among theatrical writers...."[171]

Poem: "The Sphinx of New York by Jenny Wagner" – by Merrill.[172]

By this time Merrill was earnestly trying to expand her writing skills for a musical. To producer William Harris Jr. she presented an idea for a dramatic musical revue. Harris prematurely suggested staging the work by November 1922.[173] Subsequent notices indicated the play was intended for Fay Bainter, and that Merrill had gone to the country to concentrate on writing.[174] By December 25, 1922, Fay Bainter opened in the play The Lady Christilinda which was produced by Harris. Merrill was not involved.[175]

Belle Baker's appearances in the 1922–23 season prompted some attention. In October 1922 she was performing at the Palace. Her act included some songs by Merrill, including "The Bootlegger's Slumber" which one critic called "a Wop number." Baker would enter the stage wheeling a baby carriage. The song, sung with an Italian accent, told of how she married Tony who gave up his profession ("a pick in the street") to be a bootlegger. Married only two months, she pushes around a baby carriage which everyone thinks contains an infant, evidently conceived well before marriage. "It hurts my pride / because I'm only a two months' bride / and everybody thinks I have a baby inside." But the words of the chorus revealed the true situation. The chorus began "I am now the mother of a case of Scotch" and Baker revealed that the baby carriage was filled with liquor bottles. The song was received with enthusiasm.[176] But with Prohibition recently put in place, the Palace's house manager warned Baker not to repeat the song. She disregarded his warnings, apparently with the approval of the audience. The conflict made the headline on page one of Variety.[177]

Merrill also wrote an act for Lillian Lorraine.[178]

Mollie Fuller

Merrill became involved with Mollie Fuller during 1922. Fuller had been a vaudevillian with her husband, Frederick Hallen. After Hallen's death in 1920, Fuller became blind after an unexplained ailment. In 1922, her predicament was uncovered and reported on by Variety columnist Nellie Revell who had learned of Fuller's situation after being briefly hospitalized at St. Vincent's Hospital (where Fuller had been hospitalized).

It was through Revell's column that Blanche Merrill befriended Fuller. Merrill would visit Fuller at her residence in the Palace Hotel "talking to her and learning her thoughts." Though Fuller had been in a depression, when she learned that Merrill was writing and act for her, her spirits picked up. The act was originally called Rocking and Knocking. "Miss Merrill explained she would write a vehicle that would surmount Miss Fuller's blindness in so far as an audience was concerned. The scene of the comedy will be a hotel in the mountains, with Miss Fuller and a companion in rocking chairs on the porch. While rocking they will do "knocking" of everything currently in the day's topics." Fuller's performances were arranged by the B. F. Keith Circuit. Both Merrill and Keith contributed their services to the act without remuneration,[179] and Merrill had paid production costs.[180] By the time the Fuller's act was first presented in Paterson, New Jersey, it was called Twilight and was judged a success.[181]

When Twilight opened at the Palace in New York City it garnered much applause and many curtain calls. One critic commended Merrill for obscuring Fuller's blindness, and for a hopeful if stereotypical concluding speech in which Fuller said "Hour and hour in every way, I'm getting better."[182][183] A different reviewer took a more critical stance, saying that Twilight was not up to Merrill's standard. The reviewer indicated the bad taste of some lines, such as: "They say that Eva Tanguay was married to Jack Norworth" – "Well, who wasn't?" This same writer acknowledging that Merrill was in part responsible for Tanguay's success (although not mentioning that Merrill had written material for Nora Bayes, Norworth's ex-wife). The reviewer judged that sentimentality was not Merrill's strong point, and the recitation of so many long-dead thespians was "something anyone could write." The critic concluded that Fuller should be able to stand on her talents rather than appeal to sympathy.[184] Despite that one negative review, by August 1923 Twilight had been booked for 45 weeks.[185]

One of the supporting roles in Twilight had been played by Bert Savoy, who died in June 1923. Merrill wrote a small epitaph for Variety:

Bert didn't have time to whisper a little last goodbye,

He didn't know he'd have to go at that hasty call from the sky—

The day that started out with joy, ended with a sigh,

And we found that the man who made us laugh could suddenly make us cry."[186]

Nellie Revell, the columnist who had first publicized Fuller's situation, took full advantage of the publicity afforded to her friends Fuller and Merrill. She wrote "Blanche Merrill is the most sought-after "name-your-own-price" writer of stage material in America. She is young, talented and vivacious. She is inundated with invitations to go where there is youth and life, but she prefers to spend her spare time with her blind friend Mollie Fuller.[187]

In January 1925 Variety indicated that Merrill was writing new material for Fuller.[188] The new skit was called An Even Break and was also designed to disguise Fuller's blindness, a disability of which the audience was totally aware.[189][189][190] In it, Fuller played a scrubwoman in a fancy dress shop. Various customers come and go, regarding the scrubwoman with condescension. When one customer wants to model a new dress, she insists the scrubwoman try it on first. As the scrubwoman is trying on the dress, she reminisces about her past days when she was an actress in the theater. The moral of the story was "All we get out of life is an even break."[191]

Opening at the 81st Street Theatre, the act did not receive the same rapturous approval as did Twilight although reviews were generally positive.[191] One later review indicates that the act's moral was turned into a song, "The Best That You Get When You Get It is Only an Even Break."[190]

Fuller appeared to have finally retired from the stage after An Even Break. After several near-death scares (with Revell anxiously reporting on Merrill's devotion to Fuller),[192][193] Fuller moved to California and was supported by the National Vaudeville Association until her death in 1933.

1923

Activities for Merrill in 1923:

- Under the direction of Edwin August (engaged by Marcus Loew), the Delancey Street theater proposed using amateurs from the audience to participate with professionals in creating films which will be shown the following week. The skit is called "The Great Love" and authored by Blanche Merrill.[194] Each film will run approximately 2,500 feet. First attempt will be during week of February 26.[195]

- Supplied lyric for song "(Poor Little) Wall Flower" for musical "Jack and Jill" (music for the song and most of the show was composed by W. Augustus Barratt).[196][197]

- Sylvia Clark appearing in the act Artistic Buffoonery by Blanche Merrill beginning April 9 at the Orpheum Theatre in Denver.[198]

- After a return from abroad, Beth Tate will have material written by Merrill.[199]

- Elida Morris, recently married, will continue her theatrical career. Has a new act in preparation written by Blanche Merrill.[200]

- A notice in Variety listed those would be performing material by Merrill next season: Belle Baker, Fanny Brice (for the show Laughing Lena which never materialized), Sylvia Clark, Beth Tate, Rita Gould, Lillian Show and Hughie Clark.[201]

- The music publisher Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. sued lyricist and publicist C.F. Zittel who, unauthorized, was making a film using the title "Yes, We Want No Bananas" which was too close to the song "Yes! We Have No Bananas." The scenario of the propoposed film was to have been written by Blanche Merrill.[202]

As a result of the thought of Henry Ford running for political office, Variety published Merrill's satirical lyrics to a song called "It's All a High Hat." (There is no other evidence of this song beyond these published lyrics.)

Verse:

Now lizzie used to be a name but now it's just a joke;

And the man who made us laugh at it is Ford;

He makes us laugh again—he thinks that of all men

He's the only one to be the President—but then

Chorus:

It's all a high hat—just a great big high hat

That he'll find when election comes round;

He made all those millions—now we'll hand him that,

But will he sit in the chair where Abe Lincoln once sat?

He took a tin can and he found that it ran,

Now he hears the presidential call—

He has a good business head and his heart may be large,

But who wants to see the White House turned into a garage?

It's all a high hat—just a great big high hat,

That don't mean a thing after all.[203]

1924

Evidence of Merrill's concern over unauthorized use of her material was probably relieved in part by her new contracts she put in place at the outset of the 1924–25 season. The new contracts stipulated that her material remains her property, when either performers leave a show or when the show closes. The article noted that this had become the typical procedure for most vaudevillians.[204]

In 1924 Merrill wrote a vaudeville act, Life for Mabel McCane which first played at Poli's Capitol Theatre in Hartford, Connecticut.[205] A critic wrote "One of the best shows yet" by McCane in Merrill's "Life" (acknowledging that it was the performer and the writer who were responsbile for the act's success).[206] Over the next year, wherever McCane took the act, it was well-received. Merrill's writing led one critic to observe of McCane's performance that "she runs the gamut from rags to riches, with a concluding vamp-expiring, flop down a stairway that brought thunderous applause from all parts of the auditorium."[207] The opening song was "It's a Dog's Life" in which McCane is a nurse who pushes around a baby carriage, surprising the audience that she pushes around a dog rather than a baby. The second song, "What Is It Happened To Me?" was a reflective number followed by a sentimental song, "I'll Get Along Somehow." After recovering she finds the determination to be a vamp and sings "I'm Goin' To Be Bad" and concludes with the song: "The Girl I Used To Be.[208] By April of the following year, McCane had refined the act so much that a critic wrote: "She has a gem of a character song recital, Life by Blanche Merrill, that is original and distinctive and should prove to be a winner in a feature spot on any big bill."[209]

For the Ziegfeld Follies of 1924 Merrill wrote two songs for Edna Leedom. One of them, "There's Dirty Work Somewhere in Denmark" was removed by Ziegfeld, who asked Merrill to write a replacement. The replacements were "The Buckwheat Cake Tosser in Childs" and "If Anything Happens, It Happens To Me."[210] One critic was particularly taken with "The Buckwheat Cake Tosser," noting that the performer sang "the batter is the better" way to attract men. The line that received much audience approval was:

"If King George came to this country

And walked in on this scene,

And ate one of my hot cakes—

Well God Save the Queen!"[211]

Other significant events for Merrill in 1924:

- Wrote a new song for Eva Tanguay, "I Don't Care Any More Than I Used To";[212]

- Wrote an act for Alma Adair;[213]

- Wrote The Spirit of Broadway, an act for Lida Morris;[214]

- Wrote new songs for Cecil Cunningham;[215]

- Wrote new material for Evelyn Nesbitt who was transitioning from cabaret back to vaudeville;[216]

- Wrote songs for Sylvia Clark which will well received;[217]

- Was commissioned to write material for Amazar (brought to the U.S. by John Murray Anderson play in the Greenwich Village Follies; left that show to try out vaudeville;[218]

- New songs for Belle Baker who was embarking on a tour of the Keith circuit;[219][220]

1925

Among Merrill's notable accomplishments for 1925 was a vaudeville act she wrote for Ann Butler (who was assisted in the act by Hal Parker). Called So This Is Love, the act contained four sections: Today, Tomorrow, Another Day, and Seven Years Later. In the first section, Butler appeared as an artist's model with a Yiddish accent, wishing to become an actress. In the second section, having lost her accent, she is a chorus girl, stepping out of the stage door while pining for an impoverished man; in the third section the woman and man are together and very affluent, but he wants to divorce her; she recognizes that gold is the reason for her troubles and sings a song "I Was All Right When Things Were All Wrong,"; in the final section they have six children and are poor once again. Although an October review noted that the final scene could do with improvement,[221] by December another critic wrote that the act was "..written in that clever author's most sparkling style" and that with a few changes, Butler and Parker were "ready for the big time."[222]

Noted accomplishments for Merrill during 1925 included:

- Merrill was engaged to write material for "Puzzles" (a revue starring Elsie Janis, eventually titled Puzzles of 1925).[223] Her name was included in the credits for opening night.[224] A few weeks after openings, Merrill wrote the song "When the Cat's Away" for Dorothy Appleby;[225]

- Jimmy Hussey included in his act two new songs by Blanche Merrill, "Old Established Firm" and "We're Jumping Into Something";[226]

- Merrill wrote a new act for Ruth Roye;[227]

- Merrill wrote a skit for Whiting and Burt called A Good Night;[228]

- Wrote material for Earl Carroll Vanities of 1925 [229][230] (opened July 6, 1925);[231]

- In July 1925, Variety announced the planning for a forthcoming musical version of Jack Lait's 1914 play Help Wanted. Merrill was to write the lyrics, Con Conrad would compose the music, and the musical would be staged by Earl Lindsay and Nat Philips. The notice said rehearsals were to start August 1, 1925.[232] Apparently this project did not materialize.

- Wrote act for Ray Trainor, former announcer for the Hilton Twins;[233]

- Wrote a monologue for Billy Abbott who would appear at Loew's American Theater;[234]

- An end-of-the-year advertisement for Nan Traveline includes prominent mention of "Material by Blanche Merrill."[235]

During part of this year, Merrill wrote a weekly column for Variety. Called "Weeping Singles," the column attracted attention, including some who accused Merrill of being portrayed by her.[236]

Before Merrill's departure for Hollywood, the last new skit that appeared was written for Pauline Saxon and Ralph Coleman.[237] An article from November 11, 1925 indicated that Merrill attended numerous parties intended to wish her well on her Hollywood journey.[238]

1925-1927: Hollywood

Initial news of Blanche Merrill being involved with the film industry appeared in July 1925. A report indicated that she has been tried out as a scenario writer "with much success" and had written a story called "The Seven Wives of Bluebeard."[239] This initial report[237] was confirmed when Merrill signed a contract with Joseph M. Schenck. Arranged by her agent, Jenny Wagner (who was also Fanny Brice's agent[240]), this contract gave her a weekly salary of $750, and would provide an additional $5,000 for each scenario or adaptation that she provided. Merrill departed for Hollywood in November 1925 for "a six month experimental visit."[238] An exclusive contract, it would prevent her from doing vaudeville work during her time in Hollywood.[237]

Filmed at the Cosmopolitan Studios and produced by First National,[241] the Merrill's initial story was eventually released on January 13, 1926 as Bluebeard's Seven Wives.[242] Merrill and Paul Schofield received credit for the story. A satire of the film industry, reviews of Bluebeard's Seven Wives were positive. A reviewer in Variety said: "The picture is a gag from start to finish, with the picture industry the butt of the joke,"[243] while Mordaunt Hall in the New York Times said: "A good-natured, wholesome and humorous travesty on life in the motion picture world..."[244]

Having found success on her first assignment, Variety predicted a good future for Merrill in Hollywood. Successive reports had Merrill working on a number of different projects. None of them appeared to have been produced.

- A Variety article mentioned a second treatment, "French Dressing"; nothing seems to have come from this effort.[237])

- Merrill was to do an adaptation of the story "My Woman" to be produced by United Artists.[245][246] The film was to have featured Joseph M. Schenck's wife Norma Talmadge and co-star Thomas Meighan. But Schenck decided not to have Talmadge or Meighan and instead use featured players instead of stars.[247] The film does not appear to have been produced.

- Variety mentioned Merrill was doing another screenplay for Schenk, this time of the Edward Sheldon play Romance.[248] (Originally filmed in 1920, Romance was filmed again in 1930 for Greta Garbo.)

- Schenck loaned Merrill to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer where she worked on a story about vaudeville life that was to be produced by a unit under Harry Rapf.[249]

- In March 1926, Variety reported that Merrill was adapting John B. Hymer's story The Timely Love for the screen, which was to star Norma Talmadge.[250]

- In May, Variety reported that Merrill was working at Famous Players Studios as an adapter.[251]

Apparently while in Hollywood, Fanny Brice contacted Merrill to work on new material. However Merrill's contract with Schenck precluded her from writing for external clients.[252] Despite being enjoined from writing for the stage while under contract, Nellie Revell in a 1927 Variety column stated "Nearly every musical show playing here has one or two of her numbers...There's no one who can write her material like Blanche Merrill."[253]

The series of unrealized projects ended when Merrill became involved with the Duncan Sisters and their ill-fated film Topsy and Eva. Well-known on Broadway and in vaudeville, the Sisters had one of their most popular acts, "Topsy and Eva" fashioned into a play by Catherine Chisholm Cushing which opened on Broadway in late 1924. (The characters were based on the novel Uncle Tom's Cabin.) Thinking it good material for a film, First National Pictures purchased the story and began to fashion a screen treatment. The Duncan Sisters, however, were dissatisfied with First National's proposed treatment and wouldn't sign with them.[254] Instead, the sisters signed a contract with Joseph M. Schenck who would make the film for United Artists. (The Sisters achieved a $50,000 salary and a percentage of the profits.[255]) After acquiring the rights from First National, Schenck engaged Merrill to write the story and continuity.[256] Schenck also engaged Lois Weber as director. She worked on the story even more until she was replaced as director by Del Lord, who was in turn replaced by D. W. Griffith who shot the final scenes.[257] Variety blamed the picture's poor quality on its troublesome production, but tried to be charitable: "The picture is not going to draw heavy grosses and it is not going to please all around...It will do, however, and nicely for the kiddie matinee."[257]

The film of Topsy and Eva represented the conclusion of Blanche Merrill's involvement with the movie industry, although she wrote a vaudeville skit for Our Gang alumni Mary Kornman and Mickey Daniels and would work for Rosetta Duncan once returning to New York City. According to a relative, her lack of success in Hollywood was in part due to being stereotyped as "the schoolteacher from Astoria."[258]

1926-1930: West Coast vaudeville

In April 1926, Variety announced that Charles J. McGuirk had written a short story based on Merrill's "writing to order" method that she used to write songs and acts for so many stars. Tentatively titled "The Song Modiste," the story was about 3,000 words and would be published in Everybody's Magazine. (The announcement also mentioned that Merrill was staying at the Dupont Hotel in Hollywood, CA.)[259] The story was never published.

While working in Hollywood, Merrill purchased "a lovely Spanish villa" with a grotto.[260] In addition to her film work, she was able to write material for performers based in Hollywood.

George A. Whiting and Sadie Burt were a vaudeville duo. They sang Merrill's song "What Price Love," with Saide as a gold digger and George countering.[261] Six months later, a critic called Merrill their "mascot" as he reviewed their latest skit that included The Merrill song "Jumping Into Something," about a matrimonial affair. The critic called it "a perfect gem."[262]

Others vaudevillians and movie actors based on the west coast included Benny Rubin (who sang the song "Society Debutante" that Merrill originally wrote for Fanny Brice[263]), Bobby Folsom,[264][265] Corinne Tilton,[266] and Myrtle Hebard[267]

In 1927, a notice in Variety stated that, while out in Hollywood (filming My Man), Brice would be doing an act "with sixteen gag men" to play at the Music Box Theatre in Los Angeles. Supposedly Merrill would be writing new material, and Arthur Freed would be "scoring" them.[268] But the reviewer was not impressed and made it clear that "every one of her numbers had been seen many times during her vaudeville tours." Apparently on the same program Marie Callahan and Billy Hanson did sing a new song by Merrill and Arthur Freed, "Quack, Quack."[269]

Mary Kornman and Mickey Daniels, both recently retired from Hal Roach's Our Gang film series, began appearing in vaudeville in 1926. One of their first skits was written by Merrill (the Billboard critic said the material was written by Merrill and Peter Leonard). Called "A Day Off," Kornman and Daniels used it as they began appearing on the Orpheum Circuit, debuting at the Orpheum in Los Angeles.[270] The act began with Kornman and Daniels talking about leaving "Our Gang," followed by them doing imitations of movie stars. The Billboard critic was harsh: "...Much of the material could be improved. It is only the fact that they are well known in the movie world that puts them over, as the turn does not satisfy as a two-a-day attraction. They will fare well, we believe, from the applause standpoint on account of their photoplay activities.[271] The critics at Variety were much more enthusiastic: "The material is all snappy and no easy task for anyone to handle because of its sophisticated mincing of such screen stars as Mae Murray, W.S. Hart, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford...about 15 minutes for this dialog and smart patter and not a minute of the time is wasted...Miss Merrill is entitled to full credit, as she gave the kids their selling arguments."[272] Another critic: "A smart and sophisticated burlesque turn that Blanche Merrill found time to write for them. The act is a wow and if it is not hopped onto fast by the vodvil bookers will undoubtedly be snatched up by the picture house buyers."[273] Half a year later Mary Kornman took ill and was replaced by Peggy Eames. "The kids have been given great material by Blanche Merrill and sell it."[274]

In fall 1927 it was reported that Merrill was writing a comedy sketch for Priscilla Dean and Belle Bennett. Harry Weber would be sponsoring both film stars as Dean would do singing and comedy, and Bennett would do comedy.[275] As the concept evolved, Bennett appeared to be dropped and concentration focused on Dean, who would do a monologue with songs.[276] Dean appeared at the Loew's in Hillside, Queens on February 2, followed by an appearance in Yonkers, New York.[277] As the act evolved, Franklyn Farnum was brought in and Merrill wrote a sketch called "A Broadway Cleopatra."[278]

Among the successes was at least one controversy. Actress Edna Bennett sued Merrill for failure to write and deliver a vaudeville skit. The case was settled out of court.[279]

Merrill prepared act for Nancy Welford. Called by a critic "A miniature version of 'Sally in Our Alley'," in five scenes, it told the story about plain woman who finds Broadway successes but doesn't forget her beginnings and returns for a reunion. It opened at the Orpehum Theatre in San Francisco on December 24.[280] A critic noted that it might have been a bit over the heads of the audience but was "agreeably accepted."[281]

Merrill coaxed vaudevillian Winona Winter out of retirement to appear in a sketch of her own creation. Called "Broadway-o-grams" it consisted of impersonations of notable actors on Broadway. Working the Orpheum Circuit, Winter opened at the Golden Gate Theatre in San Francisco.[282][283][284]

The next news that appears concerning Merrill in Variety indicated that Merrill arrived in London in late November 1929 having come via Cape Town.[285]

1929-1930: England

One of Merrill's first jobs in England was writing for the team Walter Fehl and Murray Leslie as well as for Fehl's wife Dora Maugham. A result was "The Thief," a vaudeville act written for Fehl and Leslie.[286] Apparently their comedy stemmed in part from Fehl being a native British person while Leslie was an American. Using the same style of sentence fragments that would be familiar to readers of Variety, a British review stated that the act had "a novel opening revealing Fehl as a gentleman and Leslie as a Jewish policeman. Cross-talk, gags, generates a good deal of laughter. Should be better as they work it.[287]

An end-of-the-year review states that, despite being ill, Dora Maugham sang "a new song cycle by Blanche Merrill" at the London Palladium on December 30, 1929[288] where she portrayed a "bad, bad woman."[289] On the bill along with Fehl and Murray at the Kilburn Empire Theatre in London, a reviewer wrote: "Blanche Merrill has written each of these two acts, and very effective material it is."[288] Maugham would later appear in America and continue her professional relationship with Merrill.

Merrill created an act for the team Vine and Russell ("the first English act to do Blanche Merrill material"[290]); nearly a year later they were still doing well on the material she had supplied.[291] Merrill also wrote for Julian Rose and Ella Retford.[292]

Having been away from New York City for five years, Merrill arrived back in the city in October 1930[293] and set up office at the Park Central Hotel.[294]

1930—1939

Upon her return to New York City, she found an apartment at the Grenfell Apartments in Kew Gardens.[295]

Among her first commissions after arriving back in New York City was to write new material for the singer Dora Maughan who had also come to America.[296] Maughan had appeared at the 86th Street Theatre in New York City in July. Variety was appreciative of Maughan and Merrill's material: "It's some of the vaude authoress' best yet and Miss Maughan makes each lyric couplet ring the bell for a laugh.[297] It was received with less enthusiasm by Billboard: "The less written about this act the better...Most of the stuff is out-and-out dirt."[298] By the beginning of 1931, Maughan's act reached The Palace. With a combination of older and newer material from Merrill, the reviewers acknowledged the nature of the material but were more positive. Variety wrote "Spice enough to give any puritannical mind Bright's disease. Strictly for adult audiences, and carrying a bigger double-entendre kick for them than any lady single on the loose...Miss Maugham is not always refined, but she is never dull."[299] Even Billboard was positive: "She uses a nifty and sure-first style in wielding the material. Combined with the fact that the material is there for laughs, it was easy for her to bat a high average."[300] (Ten years later, Maughan's reviewer complimented her "sophisticated songs, excellent material by Blanche Merrill which the seasoned comedienne whips over to 52nd Street with the same boff as she did in London and Paris..."[301])

Former customers also approached Merrill for material: Belle Baker,[302] Irene Ricordo,[303] and Lillian Shaw.[304]

In 1930, the Duncan Sisters separated temporarily when Vivian married Nils Asther and moved to England. Remaining in the United States, Rosetta Duncan embarked on a solo career. Apparently recalling the connection they had made in Hollywood, Rosetta commissioned material from Merrill and created an act based on a combination of older and new Merrill material. According to reviews, Rosetta opened the act in blackface and her traditional Topsy costume. For the second number Duncan went back to whiteface and came out dressed as a child who was experiencing a toothache. The next portion of the act had Duncan appear as a rube, wearing odd shoes, long coat, straw hat, glasses and whiskers. She closed the act with another Topsy skit. One review said that the act "showed her versatility." [305] Another summarized and acknowledged the writer: "Her material, by Blanche Merrill, is as much as Rosetta could desire, and so expertly delivered, it is high powered entertainment."[306]

By the mid 1930s, Merrill was trying to get a foothold in radio. She was hired to provide scripts for Lulu McConnell, Nana Bryant and the Duncan Sisters.[307] The audition show for McConnell took place in November 1934.[308] Apparently it was somewhat successful; Billboard identified an appearance of Lulu McConnell on Al Jolson show May 18, 1935 with a sketch by Merrill.[309] In 1936, Variety columnist Nellie Revell reported that Merrill was "peddling radio scripts."[310]

After unsuccessful attempts in the past, her professional friends had been lobbying ASCAP for three years to accept her as a member. Finally in 1936, Merrill became a member of ASCAP.[311]

A 1932 notice in Variety stated that Merrill was staying at a New Rochelle retreat and was preparing new material for Brice once Brice leaves her current show Crazy Quilt (opened on Broadway as Sweet and Low).[312] Apparently that did not happen, because a 1936 Variety notice mentions that Merrill would be writing a song for Brice "for the first time in seven years." The song was "Trailing Along in a Trailer" and was sung at the opening of the Ziegfeld Follies of 1936 at the Winter Garden on September 14, 1936. A Variety critic's review stated: "In the era of big-time vaudeville Miss Merrill was outstanding as a contributor of lyrical numbers, particularly for Miss Brice's headlining appearances."[313] Apparently that song was the last that Merrill wrote for Brice.

As Fanny Brice transitioned from stage to radio, she all but abandoned her singing career to concentrate on her Baby Snooks character. Although Brice claimed inventing the character in 1912,[314] in a 1938 Variety article, Blanche Merrill took credit for creating the Baby Snooks character. "Miss Merrill created the 'Baby Snooks' character, revived recently by Fannie Brice. It dates back to 1916 when Miss Brice used similar numbers in vaudeville such as 'We Could Only Take Their Word' and 'Poor Little Moving Picture Baby.'"[315]

After a "major operation" in December 1936, Merrill convalesced in Madison, New Jersey and wrote material for Harry Richman[316][317]

In 1938, Merrill opened offices in conjunction with music publisher Irving Mills whose company was Mills Music.[315][318] Her hope was to devote time writing material for radio. The association with Mills undoubtedly led to the publication in 1939 of "Fanny Brice's Comedy Songs," a compilation of songs all with lyrics by Blanche Merrill, most with music by Leo Edwards. With the exception of "I'm an Indian," none of the songs had been previously published, although nearly all of them had been written in the early 1920s.[319] A notice in Variety indicated future publications with lyrics by Merrill devoted to Eva Tanguay and Lillian Shaw although these never materialized.[320] Ultimately she was not successful in steady work in radio and essentially retired.[258]

1940—1948

In the 1940 United States Census, Blanche Merrill is found living with her sister Clara Kissane at her apartment at 35–55 80th Street in Jackson Heights, Queens, New York.[321] Merrill's name appears"Blanche O. Dreifuss." Clara, a school teacher, listed her annual salary at $3,830. Blanche Merrill's annual salary is listed as $700.[322]

In 1940, Merrill was engaged as one of the writers to supply material for a revue. It was to be produced by Leonard Sillman and, like others in his series of revues, provisionally titled New Faces. The revue would have brought back movie actors Joe Cook and Patsy Kelly to Broadway. Others names floated as possible cast members were Pert Kelton and Rags Ragland.[323] As work progressed, the show was renamed to All in Fun with songwriters Baldwin Bergeson, June Sillman and John Rox, although Merrill was still considered the main songwriter.[324] BMI acquired the music rights.[325] When the show opened on December 27, 1940, of all the performers mentioned, only Pert Kelton remained. Merrill's name was not on the credits. The show ran for three performances before closing.[326] One of the people in the cast was Imogene Coca whose apparent connection to Merrill would be useful ten years later.

In 1942 Variety indicated a plan for Horn & Hardart to have a radio show aimed at children, different from their long-running The Horn and Hardart Children's Hour. It was to be called Automatically Yours (a pun since Horn & Hardart had a chain of automats) and would have included songs by Blanche Merrill and Leo Edwards (the notice does not indicate whether these were new songs or revivals of materials the pair had written in the 1920s).[327]