Blainville's beaked whale

| Blainville's beaked whale | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Ziphiidae |

| Genus: | Mesoplodon |

| Species: | M. densirostris |

| Binomial name | |

| Mesoplodon densirostris Blainville, 1817 | |

| |

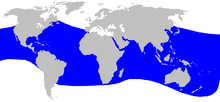

| Blainville's beaked whale range | |

Blainville's beaked whale (Mesoplodon densirostris), or the dense-beaked whale, is the widest ranging mesoplodont whale and perhaps the most documented. The French zoologist Henri de Blainville first described the species in 1817 from a small piece of jaw — the heaviest bone he had ever come across — which resulted in the name densirostris (Latin for "dense beak").[2] Off the northeastern Bahamas, the animals are particularly well documented, and a photo identification project started sometime after 2002.

Taxonomy

Blainville named the species Delphinus densirostris, based on the description of a nine-inch piece of rostrum of unknown origin housed in the Paris Museum. The second specimen, a complete skull sent from the Seychelles by a M. Leduc in 1839, was named Ziphius seychellensis by the English zoologist John Edward Gray in 1846; the French scientist Paul Gervais later placed this specimen in the genus Dioplodon ("two-toothed").[3][4]

Description

The body of Blainville's beaked whale is robust, but also somewhat compressed laterally compared with other mesoplodonts. The males have a highly distinctive appearance, the jaws overarch the rostrum, like a handful of other species, but does it towards the beginning of the mandible and then sloped down into a moderately long beak. Before the jaw sloped down, a forward-facing, barnacle infested tooth is present. One of the more remarkable features of the whale is the extremely dense bones in the rostrum, which have a higher density and mechanical stiffness than any other bone yet measured.[5] At present, the function of these bones is unknown, as the surrounding fat and the brittleness of the bone make it unlikely to be used for fighting.[5] It has been suggested that it may play a role in echolocation or as ballast, but without sufficient behavioral observation, this cannot be confirmed.[5] The melon of the whale is flat and hardly noticeable. Coloration is dark blue/gray on top and lighter gray on the bottom, and the head is normally brownish. Males have scars and cookie cutter shark bites typical of the genus. Males reach at least 4.4 m (14 ft 5 in) and 800 kg (1,800 lb), whereas females reach at least 4.6 m (15') and 1 tonne (2200 pounds). Juveniles are 1.9 m (6 ft 3 in) long when born and weigh 60 kg (130 lb).

Population and distribution

This species of beaked whale is found in tropical and warm waters in all oceans, and has been known to range into very high latitudes. Strandings have occurred off Nova Scotia, Iceland, the British Isles, Japan, Rio Grande do Sul, South Africa, central Chile, Tasmania, and New Zealand. The most common observations take place off Hawaii, the Society Islands, and the Bahamas. The species does not migrate. It inhabits water 1600 to 3000 feet deep. Despite the relatively common nature of the whale, no population estimates are available.[6]

Behavior

Blainville's beaked whales are seen in groups of three to seven individuals. Research has shown that these whales typically fall silent above 170 meters, probably in order to avoid Orcas from preying on them.[7]

Diving

The dives of Blainville’s beaked whales feature long dive times and short surface intervals. They are among the longest and deepest divers of any cetacean, with the deepest documented dive being 1,599 m. The species dives primarily to forage for food in the deep ocean, usually diving >800 m when foraging. It is thought that foraging at these depths helps to avoid predators that hunt in mid-depth waters, such as large sharks or killer whales.

In a study published in 2008, diving statistics of beaked whales were analyzed and no significant difference was found in diving behavior between day and night. For example, mean and max duration, number of deep dives, max depth, and ascent and descent rates were all calculated as equal during the day and night. However, number of mid-depth dives was recorded to be six times higher during the day than at night. These results suggest that Blainville’s beaked whales forage the same amount during the day and night, but switch to deeper-water prey at night. [8]

Foraging

Blainville's beaked whales do not capture prey by jaw. They use suction feeding to capture prey. They create low pressure in mouth by retracting tongue, and using throat grooves to expand throat volume. This creates a lower pressure in the mouth than the surrounding waters, allowing the whale to suck in water and whole prey[9].

Feeds primarily on squid, fish and other invertebrates. It probably feeds mainly on squid; the stomach of one stranded individual contained only squid.[10]

Communication

Blainville's beaked whales can live in small cohesive groups while simultaneously spending close to 80% of their life in silence. While living in these groups individuals can be separated by hundreds of meters. It is believed that these beaked whales will use their sound as a sensory cue in order to not be separated from their group. Because Blainville's beaked whales almost exclusively vocalize while on their dives, most believe that they are using sound to help their foraging. However, while on their dives they will produce whistles which are most commonly known for communication among odontocetes rather than echolocation for foraging. This has left the true meaning of the Blainville's beaked whales vocalization a mystery. [11]

Conservation

The beaked whale has occasionally been hunted, but has never been a specific target.[6] Blainville's beaked whale is covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBANS)[12] and the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS).[13] The species is further included in the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia (Western African Aquatic Mammals MoU)[14] and the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MoU).[15]

Specimens

- MNZ MM002350, collected Tongoia Beach, North of Napier, Hawke's Bay, New Zealand, 1998

- The Queensland Museum in Brisbane, Australia, has a full skeleton of an adult male on permanent display.

Gallery

Adult male (in the Bahamas)

Adult male (in the Bahamas) Mouth of adult female

Mouth of adult female A cow-calf pair surfacing

A cow-calf pair surfacing

References

- ↑ Taylor, B.L.; Baird, R.; Barlow, J.; Dawson, S.M.; Ford, J.; Mead, J.G.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Wade, P. & Pitman, R.L. (2008). "Mesoplodon densirostris". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2008: e.T13244A3426474. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T13244A3426474.en. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ↑ Sharks and Whales (Carwardine et al. 2002), p. 357.

- ↑ Raven, Henry C. 1942. On the structure of Mesoplodon densirostris, a rare beaked whale. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. LXXX, Art. II, pp. 23-50.

- ↑ True, F.W. 1910. An account of the beaked whales of the family Ziphiidae in the collection of the United States National Museum, with remarks on some specimens in other American museums. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- 1 2 3 Curry, J. (1999), "The design of mineralized hard tissues for their mechanical functions", Journal of Experimental Biology, 202: 3285–3294

- 1 2 "Office of Protected Resources: Blainville's Beaked Whale (Mesoplodon densirostris)". Office of Protected Resources. Retrieved March 21, 2010

- ↑ Walker, Matt (July 25, 2011). "Blainville's beaked whales enter stealth mode". BBC Nature. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ Baird, R.W.; et al. (2008). "Diel variation in beaked whale diving behavior". Marine Mammal Science. 24: 630–642 – via Cascadia Research Collective.

- ↑ Ito, Haruka (2002). "Suction feeding mechanisms of the dolphins".

- ↑ MacDonald, David; Barret Priscilla (1993). Mammals of Britain & Europe. 1. London: HarperCollins. pp. 179–180. ISBN 0-00-219779-0.

- ↑ Aguilar de Soto, Natacha; Madsen, Peter T.; Tyack, Peter; Arranz, Patricia; Marrero, Jacobo; Fais, Andrea; Revelli, Eletta; Johnson, Mark (2011-07-15). "No shallow talk: Cryptic strategy in the vocal communication of Blainville's beaked whales". Marine Mammal Science. 28 (2): E75–E92. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2011.00495.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ↑ Official website of the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas

- ↑ Official website of the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area

- ↑ Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia

- ↑ Official webpage of the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region

- Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Edited by William F. Perrin, Bernd Wursig, and J.G.M Thewissen. Academic Press, 2002. ISBN 0-12-551340-2

- Sea Mammals of the World. Written by Randall R. Reeves, Brent S. Steward, Phillip J. Clapham, and James A. Owell. A & C Black, London, 2002. ISBN 0-7136-6334-0

- Possible functions of the Ultradense bone in the rostrum of Blainville's beaked whale (Mesoplodon densirostris). Written by Colin D. MacLeod. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 80(1): 178-184 (2002). Available: here

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mesoplodon densirostris. |