Blacula

| Blacula | |

|---|---|

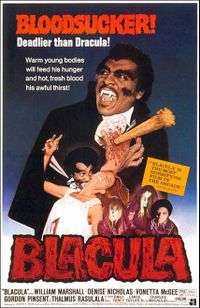

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | William Crain |

| Produced by |

Samuel Z. Arkoff Joseph T. Naar |

| Written by |

Joan Torres Raymond Koenig |

| Starring |

William Marshall Vonetta McGee Denise Nicholas Gordon Pinsent Charles Macaulay Thalmus Rasulala |

| Music by | Gene Page |

| Cinematography | John M. Stephens |

| Edited by | Allan Jacobs |

| Distributed by | American International Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Blacula is a 1972 American blaxploitation horror film produced for American International Pictures[1] The film was directed by William Crain and stars William Marshall in the title role about an 18th-century African prince named Mamuwalde, who is turned into a vampire (and later locked in a coffin) by Count Dracula in the Count's castle in Transylvania in the year 1780 after Dracula refused to help Mamuwalde suppress the slave trade.

Nearly two centuries later, in the year 1972, two interior decorators from modern-day Los Angeles, California travel to Castle Dracula in Transylvania and unknowingly purchase the now-undead Mamuwalde's coffin, which they ship to Los Angeles. Unlocking the coffin, the decorators release Mamuwalde, becoming his first two victims as a vampire, turning them and others he encounters in his bloodthirsty reign of terror into vampires like himself. Mamuwalde later meets a woman named Tina (Vonetta McGee), whom he believes to be the reincarnation of his deceased wife Luva (also played by McGee in the pre-opening credit scenes at Dracula's castle).

Blacula was released to mixed reviews in the United States, but was one of the top-grossing films of the year. It was the first film to receive an award for Best Horror Film at the Saturn Awards. Blacula was followed by the sequel Scream Blacula Scream in 1973 and inspired a wave of blaxploitation-themed horror films.

Plot

In 1780, Prince Mamuwalde (William Marshall) is sent by the elders of the Abani African nation to seek the help of Count Dracula (Charles Macaulay) in suppressing the slave trade. Dracula, instead, laughs at this request and insults Mamuwalde by making thinly veiled overtures about enslaving his wife, Luva (Vonetta McGee). After a scuffle with Dracula's minions, Mamuwalde is transformed into a vampire. Dracula curses him with the name "Blacula" and imprisons him in a sealed coffin in a vault hidden beneath the castle. Luva is also imprisoned in the vault and left to die.

In 1972, the coffin is purchased as part of an estate by two homosexual interior decorators, Bobby McCoy (Ted Harris) and Billy Schaffer (Rick Metzler) and shipped to Los Angeles. Bobby and Billy open the coffin and become Prince Mamuwalde's first victims. At the funeral home where Bobby McCoy's body is laid, Mamuwalde spies on mourning friends Tina Williams (Vonetta McGee), her sister Michelle (Denise Nicholas), and Michelle's boyfriend, Dr. Gordon Thomas (Thalmus Rasulala), a pathologist for the Los Angeles Police Department. Mamuwalde believes Tina is the reincarnation of his deceased wife, Luva. On close investigation of the corpse at the funeral home, Dr. Thomas notices oddities with Bobby McCoy's death that he later concludes to be consistent with vampire folklore.

Prince Mamuwalde continues to kill and transform various people he encounters, as Tina begins to fall in love with him. Thomas, his colleague Lt. Peters (Gordon Pinsent), and Michelle follow the trail of murder victims and begin to suspect a vampire is responsible. After Thomas digs up Billy's coffin, Billy's corpse rises as a vampire and attacks Thomas, who fends him off and drives a stake through his heart. Thomas also finds a photo negative taken of Mamuwalde and Tina in which Mamuwalde is not visible. After killing one of the undead victims in the city morgue, Thomas and Peters track Mamuwalde to his hideout, the warehouse where Bobby McCoy and Billy Schaffer were first slain. They locate and defeat several vampires, but Mamuwalde manages to escape.

Mamuwalde lures Tina to his new hideout at a nearby chemical plant, while Thomas and a group of police officers pursue him. Mamuwalde dispatches several officers, but one of them accidentally shoots Tina fatally. To save her life, Mamuwalde transforms her into a vampire. One of the policemen locates the coffin and alerts Peters. However, Peters inadvertently kills Tina with a stake, believing that Mamuwalde would be in the coffin instead. Devastated at losing her again, Mamuwalde willingly climbs the stairs to the roof where the morning sun destroys him.

Cast

- William Marshall as Prince Mamuwalde / Blacula

- Denise Nicholas as Michelle Williams

- Vonetta McGee as Tina Williams / Luva

- Gordon Pinsent as Lt. Jack Peters

- Thalmus Rasulala as Dr. Gordon Thomas

- Emily Yancy as Nancy

- Lance Taylor Sr. as Swenson

- Logan Field as Sergeant Barnes

- Ted Harris as Bobby McCoy

- Rick Metzler as Billy Schaffer

- Ketty Lester as Juanita Jones / Taxi Girl

- Charles Macaulay as Count Dracula

- Ji-Tu Cumbuka as Skillet

- Elisha Cook, Jr. as Sam

- Eric Brotherson as Real Estate Agent

- The Hues Corporation as themselves

- Rick Hochman as The Young Hoch

Production

Many members of the cast and crew of Blacula had worked in television. Director William Crain had directed episodes of The Mod Squad.[2] William H. Marshall's Mamuwalde was the first black vampire to appear in film.[2] Marshall had previously worked in stage productions and in episodes of The Man from U.N.C.L.E., The Nurses, Star Trek and Mannix.[2] Thalmus Rasulala who plays Dr. Gordon Thomas had previously been in episodes of The Twilight Zone, Perry Mason, and Rawhide.[2]

Blacula was in production between late January and late March 1972.[3] While Blacula was in its production stages, William Marshall worked with the film producers to make sure his character had some dignity. His character name was changed from Andrew Brown to Mamuwalde and his character received a background story about being an African prince who had succumbed to vampirism.[4] Blacula was shot on location in Los Angeles, with some scenes shot in Watts and the final scenes taken at the Hyperion Outfall Treatment Plant in Playa del Rey.[3]

The music for Blacula is unlike that of most horror films as it uses rhythm and blues as opposed to haunting classical music.[5] The film's soundtrack features a score by Gene Page and contributions by the Hues Corporation and 21st Century Ltd.[6]

Release

Blacula was released on August 25, 1972.[7] Prior to its release, American International Pictures' marketing department wanted to ensure that black audiences would be interested in Blacula; some posters for the film included references to slavery.[8] American International Pictures also held special promotional showings at two New York theaters; anyone wearing a flowing cape would receive free admission.[8] Blacula was popular in America, debuting at #24 on Variety's list of top films. It eventually grossed over a million dollars, making it one of the highest-grossing films of 1972.[9]

Scream Factory released the film on Blu-ray as a double feature with Scream Blacula Scream on March 2, 2015.[10]

Reception

Blacula received mixed reviews on its initial release.[9] Variety gave the film a positive review praising the screenplay, music and acting by William Marshall.[8] The Chicago Reader praised the film, writing that it would leave its audience more satisfied than many other "post-Lugosi efforts".[9] A review in The New York Times was negative, stating that anyone who "goes to a vampire movie expecting sense is in serious trouble, and "Blacula" offers less sense than most."[11] In Films & Filming, a reviewer referred to the film as "totally unconvincing on every level".[9] The Monthly Film Bulletin described the film as "a disappointing model for what promised to be an exciting new genre, the black horror film." and that apart from the introductory scene, "the film conspicuously fails to pick up on any of its theme's more interesting possibilities–cinematic or philosophical."[12] The film was awarded the Best Horror Film title at the first Saturn Awards.[13]

Among more recent reviews, Kim Newman of Empire gave the film two stars out of five, finding the film to be "formulaic and full of holes".[14] Time Out gave the film a negative review, stating that it "remains a lifeless reworking of heroes versus vampires with soul music and a couple of good gags."[15] Film4 awarded the film three and a half stars out of five, calling it "essential blaxploitation viewing."[16] Allmovie gave the film two and a half stars out of five, noting that Blacula is "better than its campy title might lead one to believe...the film suffers from the occasional bit of awkward humor (the bits with the two homosexual interior decorators are the most squirm-inducing), but Joan Torres and Raymond Koenig's script keeps things moving at a fast clip and generates some genuine chills."[17] The Dissolve gave the film two and a half stars, stating that "The placement of an old-fashioned, Bela Lugosi-type Dracula—albeit much, much sweatier—in a modern black neighborhood is a great idea, but the amateurish production leaves Marshall as stranded in the film as his Mamuwalde is stranded in the times."[10]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 48% based on 25 reviews, with a weighted average rating of 5.3/10.[18]

Aftermath and influence

The box office success of Blacula sparked a wave of other black-themed horror films.[9][19] A sequel to the film titled Scream Blacula Scream was released in 1973 by American International. The film also stars William Marshall in the title role along with actress Pam Grier.[19] American International was also planning a follow-up titled Blackenstein, but chose to focus on Scream Blacula Scream instead. Blackenstein was eventually produced by Exclusive International Pictures.[20]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gary A. Smith, The American International Pictures Video Guide, McFarland 2009 p 27

- 1 2 3 4 Lawrence, 2008. pg. 49

- 1 2 "Blacula". American Film Institute. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ↑ Lawrence, 2008. pg. 50

- ↑ Lawrence, 2008. pg. 55

- ↑ Ankeny, Jason. "Blacula - Gene Page: Allmusic". Allmusic. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ↑ Kane, 2006. pg. 153

- 1 2 3 Lawrence, 2008. pg. 56

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lawrence, 2008. pg. 57

- 1 2 Tobias, Scott (March 2, 2015). "Blacula Scream Blacula Scream". The Dissolve. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ↑ Greenspun, Roger (August 26, 1972). "Blacula (1972)". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Blacula". Monthly Film Bulletin. London: British Film Institute. 40 (468): 188–189.

- ↑ "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ↑ Newman, Kim. "Blacula Review". Empire. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Blacula Review". Time Out. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Blacula (1972)". Film4. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ↑ Guarisco, Donald. "Blacula: Review". Allmovie. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Blacula (1972) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Flixer. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- 1 2 Lawrence, 2008. pg. 58

- ↑ Lawrence, 2008. pg. 59

References

- Lawrence, Novotny (2008). Blaxploitation films of the 1970s: Blackness and genre. ISBN 0-415-96097-5. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- Kane, Tim (2006). The Changing Vampire of Film and Television. McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-2676-4. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

External links

- Blacula at AllMovie

- Blacula on IMDb

- Blacula at Rotten Tomatoes

- Official Trailer #1 on YouTube