Birmingham and Gloucester Railway

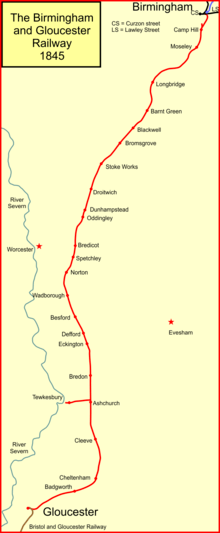

The Birmingham and Gloucester Railway was a railway route linking the cities in its name; it opened in stages in 1840, using a terminus at Camp Hill in Birmingham. It linked with the Bristol and Gloucester Railway in Gloucester, but at first that company's line was broad gauge, and Gloucester was the scene of supposedly chaotic transhipment of goods into wagons of the 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) other gauge.

The Birmingham and Gloucester Railway main line incorporated the Lickey Incline, a 2-mile (3.2 km) stretch of track climbing a 1-in-37 (2.7%) gradient in the northbound direction. This was a serious challenge throughout the period of steam traction.

In 1846 the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway was acquired by the Midland Railway. Nearly all of the original main line remains in-situ at the present day, forming part of an important trunk route.

First proposals

The idea for a railway line between Bristol and Birmingham was put forward during the construction of the Stockton and Darlington Railway. 78,000 tons of goods were conveyed from Birmingham to Bristol annually, a journey that took nearly a week, and the cost of the journey was high. At a meeting in Bristol on 13 December 1824 subscriptions were taken for a proposed Bristol, Northern and Western Railway.[1] There was considerable enthusiasm for the scheme and before the meeting closed, all the 16,000 shares allocated to Bristol were taken up. A further 9,000 shares were allocated to other locations, and the total amounted to £1 1⁄4 million. A survey was carried out in 1825 but there was a financial crisis in 1826, and the investors asked for the project to be suspended, and nothing more came of it.[2][3][4]

In 1832 a further scheme was put forward, and Isambard Kingdom Brunel was asked to survey a cheap route between Birmingham and Gloucester. He avoided the barrier of the Lickey Hills and his maximum gradient would have been 1 in 300. This scheme too failed to make progress due to lack of funds.[1][5]

Birmingham and Gloucester Railway proposed

The idea was revived when in 1834 Captain W S Moorsom was engaged to survey a route; once again economy was considered to be essential, and his route avoided large towns as the cost of land acquisition there would be heavy. There was disquiet from the by-passed towns, and Cheltenham was particularly vocal. Moorsom modified his intended route to provide a Cheltenham station, but that was not considered convenient for the centre of the town, and a branch line was proposed. When the B&GR promoters refused to contemplate the expense of that, Pearson Thompson, a prominent Cheltenham resident and a member of the Gloucester Committee of the B&GR, offered to build it himself at his own expense.[1]

At Birmingham the situation was happier; a connection to the London and Birmingham Railway close to the city was agreed, and moreover the L&BR agreed to the use of their Curzon Street railway station on payment of a toll. As well as giving a direct connection to London, and over the Grand Junction Railway to the north west of England, this avoided the expense of constructing a new terminus in the city.[1]

Moorsom estimated the cost of construction to be £920,000.[1] Moorsom's route did climb the Lickey Ridge directly, involving a long climb. This was divided into two sections: 1 1⁄4 miles at 1 in 54 worked by a 96 hp stationary engine, and 1 1⁄4 miles at 1 in 36 worked by a 121 hp machine. there was also to be an inclined plane at Gloucester to reach a goods depot at the canal, and another at the connecting line to the L&BR in Birmingham, at 1 in 84.[1]

In the 1836 session of Parliament, the Cheltenham and Great Western Union Railway was also being considered, and between Gloucester and Cheltenham the two companies proposed almost identical routing. They came to an arrangement by which they would collaborate in the construction. The line between Gloucester and Cheltenham was to be divided, the Cheltenham end being built by the Birmingham company and the Gloucester end by the C&GWUR. Each would build one of the stations and both would have freedom to run over the whole line and use both the stations. The means of dealing with the complexity of the different gauges was not fully specified at first.[1][6]

There was already a plateway tramroad between Gloucester and Cheltenham. The Gloucester and Cheltenham Tramroad[note 1] had opened in 1810. As well as connecting the two places, it had an important branch to quarries at Leckhampton, in the hills south of Cheltenham. Stone for house building was in demand at the time. Acquisition of the tramroad was sought by both the B&GR and the C&GWUR; the objective was not to use its alignment, which was unsuitable for a main line railway, but to make use of its access to Gloucester Docks. The collaborative approach to building the new main line extended to the issue of acquiring the tramroad, and it was agreed to do so jointly, for the sum of £35,000.[7][1]

Authorisation

At this stage the line was conceived as a toll railway, in which independent carriers would provide the trains, paying the B&GR a toll for the privilege. The Birmingham and Gloucester Railway was given the Royal Assent on 22 April 1836. with authorised capital of £950,000.[1][3][4]

Public opinion in Worcester was hostile to the company because of the route to be taken by the main line, far from the city. Because of the fear of competing railways companies providing that need, the B&GR agreed to provide a branch line to Worcester, from Abbotswood. Similarly Tewkesbury had to be pacified, with a branch line from Ashchurch. These were authorised the following year, by Act of 15 May 1837.[note 2][1] for extensions to Worcester and Tewkesbury.[2][4]

Construction had been delayed due to high prices and the difficulty of obtaining access to the land on the route, but in April 1837 it was started in earnest. However a group of shareholders cast doubt on Moorsom's ability and it was agreed that there would be a six week delay while an eminent engineer reviewed the technical aspects of the proposed line. This was done by Joseph Locke, and his report on the technical aspects, including the Lickey Incline, was favourable.[1]

The Cheltenham and Great Western Union Railway had been short of money from the outset, chiefly due to a Parliamentary battle over a rival proposed line to Cheltenham. In November 1837 the C&GWUR said that they would prioritise their limited funds on the section from Swindon to Cirencester. This meant failing to build their portion of the line between Gloucester and Cheltenham, on which the B&GR depended to access to Gloucester, and ultimately Bristol. The B&GR were alarmed by this; if the C&GWUR were to become insolvent and their powers lapsed, the B&GR had no powers to form the line themselves.

The C&GWUR had a Bill before Parliament in the 1838 session, and it was mutually accepted that protective clauses for the B&GR could be inserted; power was given for the B&GR to build the line itself if the C&GWUR failed to do so. The original arrangement by which shared stations would be built at Gloucester and Cheltenham was withdrawn, and it was now decided that each company would build its own station.[1]

In fact the situation foreseen by the B&GR did arise, and the C&GWUR failed to provide the line as promised; the B&GR activated the powers in the 1838 Act and built the line itself. By August 1839 the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway had four locomotives, and 35 wagons had been delivered but an early opening that was anticipated was delayed by extremely bad weather. A special journey on the line was undertaken by the Directors on 1 June 1840; in fact there were two round trips, and a number of members of the public boarded the train.[1][4]

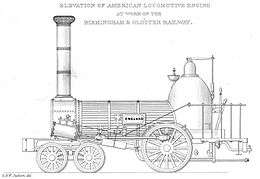

Selection of locomotives

In 1838, during the construction period thought was being given once again to the working of the Lickey Incline by locomotives. Although both Brunel and Robert Stephenson declared this to be impossible, Captain Moorsom said that he had seen locomotives working similar gradients in the USA,[note 3] An order was placed with engine builders called Norris Locomotive Works in Philadelphia for a number of 4-2-0 locomotives.[note 4][2][3] On opening there were four locomotives built by Forrester; they were named Cheltenham, Worcester, Bromsgrove and Tewkesbury. They had 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) driving wheels. There were four of the American 4-2-0 locomotives, which had 4 ft (1,219 mm) driving wheels. The four non-driven wheels were mounted on a bogie. They were named Philadelphia', England, Columbia, and Atlantic. In addition there were four ballast engines.[3]

Opening of the line

The line was opened in stages; from Cheltenham to Bromsgrove was opened to the public without ceremony on 24 June 1840 for passenger traffic. On 17 September 1840 it was extended to a temporary terminus at Cofton Farm. Cofton Farm was a short distance south of the present-day Longbridge. The Cheltenham to Gloucester section, built by the B&GR in default of the C&GWUR, was opened on 4 November 1840. [1] On 17 December 1840 the section from Cofton Farm to Camp Hill opened. For the time being Camp Hill was the Birmingham terminus of the line, and the line was complete in accordance with the original intentions.[5][3][4][8]

The Tewkesbury branch opened on 21 July 1840.[note 5][9] It was horse-operated until 1844; doubletrack was installed in 1864 in connection with the construction of the Malvern and Tewkesbury line.[8].

Finally the line was completed from Camp Hill to a junction with the London and Birmingham Railway at Birmingham on 17 August 1841. On the opening to Birmingham, the Camp Hill terminus was relegated to the status of a goods station, and Birmingham and Gloucester Railway trains used the Curzon Street station of the L&BR.[2][5][3][4][8] Goods traffic started on the line in April 1841.[2]

There was one tunnel, at Grovely Hill, near Bromsgrove; it was a one-quarter mile (0.4 km) in length, lined in brick with no invert. The largest bridge was over the Avon at Eckington, Worcestershire with three cast-iron segmental arches of 73-foot (22.3 m) span supported on two lines of iron columns.[3]

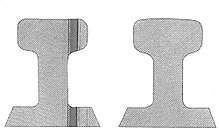

The rails were Vignoles rail weighing 56 lb/yd (27.8 kg/m), laid on longitudinal sleepers, except on embankments over 15 feet (4.6 m) high where cross sleepers were used.

The construction had cost £1,266,666.[1]

First locomotives

After the initial deliberations about locomotives capable of taking trains up the Lickey incline, a number of the American engines were obtained.[note 6] The prototype Norris engine was described as a Class A Extra locomotive, supposedly capable of taking 75 (long) tons up the Lickey incline at 10 to 15 mph. Three more of these were ordered. Norris's British agent persuaded the B&GR to purchase smaller "Class B" locomotives, and the prototype, named "England", was trialled on the Grand Junction Railway (as the B&GR was not ready) in March 1839, and found to be non-compliant with the specification as to load haulage. Undeterred, the B&GR purchased six of the class B engines. A Class A Extra locomotive named Philadelphia was delivered at the end of May 1840; it had a sand box and water tub "for wetting the rails to improve adhesion". In a trial on the uncompleted Lickey incline, it performed better than a Bury locomotive, taking 24 tons up at 15 mph.[1][4]

However Rake comments that, "The American locomotives were, however, afterwards superseded, as it was found that an ordinary tank engine, assisted by a pilot, worked the traffic in a perfectly satisfactory manner." Moreover the fireboxes and boiler tubes were iron, and soon had to be replaced with brass fittings.[3]

Early business performance

Night mail trains started running from 6 February 1841, by contract to the Postmaster General.[3]

In 1842 the difficult financial situation in the country led to a massive fall in passenger carryings, and this was to continue in 1843, and this led to difficulties in the Company's trading position.

The Bristol and Gloucester Railway opened on 8 July 1844, and the fact of through railway communication between Birmingham and Bristol, albeit for the time being with a break of gauge at Gloucester, stimulated goods traffic volumes.[2]

The Bristol and Gloucester Railway and the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway obviously had a mutual interest, and discussions took place over the amalgamation of the two companies. This was agreed on 14 January 1845, and a Parliamentary Bill was presented, but it failed Standing Orders and was withdrawn. The two companies worked in informal collaboration for the time being.

Tewkesbury

A contemporary description of the station mentions that "the front elevation is 38 feet wide, and at the back is a raised platform 133 feet by 12 feet 6 inches covered by a substantial roof with glass lights on each side. The roof measures 166 feet long by 32 feet wide".[4]

Bristol and Gloucester Railway

In 1839 the Bristol and Gloucester Railway had been authorised. It was conceived as a narrow (standard) gauge railway between a terminal in Bristol and Standish Junction, where it would make use of the Cheltenham and Great Western Union Railway into Gloucester. When the C&GWUR got into financial difficulties, it was taken over by the Great Western Railway in January 1843. The Bristol and Gloucester Railway now found that it would be running between the GWR at Bristol and the GWR at Standish, and at both places the GWR line would be on the broad gauge. The Bristol and Gloucester Railway decided to make its line on the broad gauge, and this enabled it to use the GWR Temple Meads station at Bristol, and simplified the section between Standish and Gloucester, which otherwise would have needed to be on the mixed gauge.[10][11]

The Bristol and Gloucester Railway opened for passenger traffic on 6 July 1844; it used a platform, intended for the C&GWUR, on the north side of the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway station there; the two lines crossed on the immediate approach to the stations.[12]

Absorption by the Midland Railway

On 24 January 1845 the Great Western Railway made an offer to absorb the two companies; this would have resulted in the broad gauge being extended to Birmingham. The deal was not finalised on that day, and John Ellis of the Midland Railway encountered Edward Sturge and Joseph Gibbons while they were travelling to a second meeting with the GWR on 26 January. Ellis saw the opportunity and offered that his company would purchase the Gloucester companies, and offered 6% on their capital of £1.8 million if discussions with the GWR were inconclusive. The GWR declined to increase their offer, and the Gloucester companies turned back to Ellis.[2]

The Midland's solicitor Samual Carter acquired a perpetual lease with the right to purchase.[13] The matter was ratified in Parliament in the 1846 session, and on 3 August 1846 the amalgamation Bill was passed.[2]

The London and North Western Railway was as anxious to keep the broad gauge away from Birmingham as was the Midland Railway, and it undertook to share any loss the MR might make by the acquisition; this was later commuted into permission to use the LNWR New Street station (built later) in Birmingham for a nominal rental of £100 per annum.

The taking in to the Midland company of the Bristol and Gloucester Railway perpetuated for the time being the break of gauge at Gloucester. The disruption caused by the process of transferring goods from narrow (standard) gauge wagons to broad gauge influenced the Gauge Commission, who at the time were deliberating on recommendations to Parliament about the standardisation of the gauge in Great Britain. Of more immediate concern, the Midland Railway obtained authorisation by Act of 14 August 1848 to lay an independent narrow gauge track between Gloucester and Standish Junction (where the Cheltenham and Great Western Union Railway diverged), and to mix the gauge between Standish and Bristol. They ran their first narrow gauge train throughout on 29 May 1854.[2]

Further Norris locomotives were purchased, but they were crudely constructed and early replacement of fireboxes proved to be necessary. From February 1842 several were progressively converted to tank engines.[2]

Worcester

The Birmingham and Gloucester Railway had, from the outset, implied a willingness to serve Worcester to respond to an outcry from the city over being bypassed. Railway politics intervened and the early authorising Acts of the B&GR did not include the contemplated Worcester branch.

The Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway had been authorised on 4 August 1845; it was to be a broad gauge line, allied to the Great Western Railway. A national financial recession resulted in serious difficulties for the company in constructing its line. Meanwhile the Midland Railway was anxious to reach Worcester, and the two companies reached an agreement to lay narrow (standard) gauge track between the junction at Abbots Wood (on the B&GR main line) and the Shrub Hill station at Worcester. The Midland Railway started operating a train service on 5 October 1850. There were five daily trains to Bristol and six to Birmingham; the Birmingham trains reversed at Abbots Wood Junction.[14][9][15]

Gough reports:

The Midland worked the service on the short section between Abbot's Wood Jcn and Worcester from its commencement. When the loop to Stoke Works Jcn was completed the company began to divide its passenger trains and run one section direct and one via Worcester. The trains separated and rejoined at the two junctions. By 1855 the service on the original line consisted of two trains in each direction between Bromsgrove and Abbot's Wood, making connections with trains running via the loop. From 1 October 1855 these services were withdrawn, and all regular passenger trains ran via Worcester. Goods trains and excursion traffic continued to run via Dunhampstead [the original main line]. The Dunhampstead line was re-opened for regular traffic on 1 June 1880 to allow some through trains to by-pass Worcester, but the intermediate stations were not re-opened for passenger traffic.[8]

The Direct Line at Landor Street Junction

The Midland Railway had been formed by the amalgamation of the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway with others. Both the B&DJR and the B&GR line turned westward to Curzon Street station and Landor Street, and in 1862 the Midland Railway obtained powers to construct a direct line between the two networks.

This was opened in the first half of 1864. From that time express passenger trains were run between Derby and Bristol over the direct line. Portions for Birmingham New Street station, by now opened as the main central station for the Midland Railway, were detached or attached at Saltley and Camp Hill.[5]

Birmingham West Suburban Railway

On 3 April 1876 the Birmingham West Suburban Railway was opened, as a single line from the Midland Railway at Lifford to Granville Street canal wharf, near the centre of Birmingham. It was worked by the Midland Railway, who later acquired it. The line was intended as a suburban passenger line. A connection was made at Lifford to Kings Norton on the Birmingham and Gloucester main line, and the passenger trains from Granville Street ran to that place.

In 1881 an Act authorised an extension north-eastwards, so as to connect to New Street station in Birmingham. This was opened in 1885 and from that time express passenger trains between Bristol and Birmingham used the West Suburban line. This had the added advantage of entering New Street station from the west, enabling forward running on to the Midland Railway's Derby line without reversal.[5]

Lifford Curve

In 1892 a curve was installed at Lifford forming the third side of a triangle there, and enabling circular suburban passenger train operation.[5]

Lickey bank engines

Banking on the Lickey incline remained an operational inconvenience throughout the years of steam traction. In 1920 a four cylinder 0-10-0 locomotive was built specially of the purpose; no 2290, it was known informally as Big Bertha, in association with the German heavy howitzer used during World War I. An electric headlight was provided on the engine to assist in closing up to the rear of a goods train in the hours of darkness

Later, while no. 2290 was being overhauled, an LMS 2-6-0+0-6-2 Garratt design of engine, no 4998, was used and later an LNER 2-8-0+0-8-2 Garratt, class U1, no 69999 was used in 1949.

Intermediate stations near Birmingham

During World War II intermediate stations between Kings Norton and Birmingham on the original Birmingham and Gloucester alignment were closed as an economy measure, in 1941. After the end of the war, there appeared to be little public pressure to reopen them, and they remained closed.[5]

From 1923

In 1923 most of the railways of Great Britain were restructured into four larger groups; the process had been mandated by the Railways Act 1921 and was effective from the beginning of the year. The Midland Railway as a constituent of the new London, Midland and Scottish Railway, (LMS).

Nationalisation

In 1948 the railways were again restructured by Government, and taken into national ownership under British Railways.

Concentration from alternative routes

In the early 1960s there were three routes in principal use for freight between the South West of England and South Wales on the one hand, and the West Midlands and the North West: as well as the Lickey route, they were via Hereford and Worcester, or Shrewsbury, and via Honeybourne and Stratford. The Lickey route carried the heaviest traffic by a moderate margin. Concentration, and rationalisation, was sought at the time, and by the Spring of 1965 the introduction of diesel traction had shown that the Lickey Incline was less of an operational problem than it had been; the decision was taken to concentrate the freight haulage on the Lickey route, and this enabled the transfer of heavy through freight away from the Honeybourne route.[5]

The present day

The line is an important part of the British railway network, forming a section of the Bristol to Birmingham main line.

There is (2017) a frequent long-distance passenger service operated by CrossCountry, an operating division of Arriva UK Trains. In addition London Midland operate a local passenger service from Hereford to Birmingham]], which uses the line from Stoke Works Junction to Kings Norton. The line is also an important freight route.

The former Birmingham West Suburban Railway route is used by the majority of through passenger trains and all local trains; a few through trains use the original Camp Hill route for convenience in approaching or leaving Birmingham New Street station at the east end rather than the west.

Most of the freight traffic uses the Camp Hill route, which gives better connectivity at Saltley.

The Tewkesbury branch closed in 1961 to passengers and 1964 completely.

Accidents and incidents

On 10 November 1840, the boiler of locomotive Surprise exploded at Bromsgrove. Two people were killed.[16]

Topography

- Gloucester; opened 4 November 1840; closed 12 April 1896;

- Churchdown; opened August 1842; closed September 1842; reopened 2 February 1874; closed 2 November 1964;

- Badgeworth; opened 22 August 1843; closed October 1846;

- Hatherley Junction; divergence of curve to Banbury line (1906 - 1956);

- Lansdown Junction; convergence of Banbury and Cheltenham Direct line (1881 - 1962); divergence of GWR line to St James station (1847 – 1966);

- Cheltenham; opened 24 June 1840; sometimes known as Cheltenham Spa Lansdown; still open;

- Cheltenham High Street; opened 1 September 1862; closed 1 July 1910;

- Swindon; opened 26 May 1842; closed 1 October 1844;

- Cleeve; opened 14 February 1843; closed 20 February 1950;

- Ashchurch; opened 24 June 1840; closed 15 November 1971; reopened 2 June 1997; still open; divergence of Tewkesbury branch (1840 – 1964); divergence of line to Evesham (1864 - 1963);

- Ashchurch flat crossing (1864 - 1957);

- Bredon; opened 24 June 1840; closed 4 January 1965;

- Eckington; opened 24 June 1840; closed 4 January 1965;

- Defford; opened 24 June 1840; closed 4 January 1965;

- Besford; opened November 1841; closed after August 1846;

- Pirton; opened November 1840; closed November 1844;

- Wadborough; opened November 1841; closed 4 January 1965;

- Worcester Junction; opened November 1850; renamed Abbot's Wood Junction March 1852; closed 1 October 1855;

- Abbotswood Junction; divergence of spur towards Worcester (1850 -);

- Norton; opened November 1841; closed August 1846;

- Spetchley; opened 24 June 1840; closed 1 October 1855;

- Bredicot; opened November 1845; closed October 1855;

- Oddingley; opened September 1845; closed by October 1855;

- Dunhampstead; opened November 1841; closed 1 October 1855;

- Droitwich; opened 24 June 1840; renamed Droitwich Road 1852; closed 1 October 1855;

- Dodderhill; opened November 1841; closed 5 March 1844;

- Stoke; opened about September 1840; soon renamed Stoke Works; closed 1 October 1855;

- Stoke Works Junction; convergence of line from Droitwich Spa (1852 -);

- Bromsgrove; opened 24 June 1840; still open;

- Lickey Incline;

- Blackwell; opened 5 June 1841; closed 18 April 1966;

- Barnt Green; opened 1 May 1844; still open; convergence of Redditch branch (1859 - );

- Cofton Farm; opened 17 September 1840; closed 17 December 1840;

- Cofton Tunnel; opened out 1929;

- Longbridge; opened November 1841; close 1 May 1849; reopened 1918; closed by 1927; reopened 8 May 1978; still open; convergence of Halesowen Railway (1883 – 1964);

- Northfield; opened 1 September 1870; still open;

- King's Norton; opened 1 May 1849; still open; divergence of West Suburban Line (1885 -); divergence of dive under to West Suburban Line (1876 – 1967);

- Lifford East Junction; convergence of Lifford curve;

- Lifford; opened ?; closed November 1844; reopened 28 September 1885; closed 30 September 1940;

- Hazelwell; opened 1 January 1903; closed 27 January 1941;

- Moseley; opened November 1841; renamed King's Heath 1 November 1867; closed 27 January 1941;

- Moseley; opened 1 November 1867; closed 27 January 1941;

- Brighton Road; opened 1 November 1875; closed 27 January 1941;

- Camp Hill; opened by December 1844; renamed Camp Hill and Balsall Heath December 1867; renamed Camp Hill 1 April 1904; closed 27 January 1941; divergence of connecting line to London and Birmingham Railway (1841 -);

- Camp Hill; opened 17 December 1840; closed 17 August 1841; closed to goods traffic 1970.[17][8][18]

Connecting line to London and Birmingham Railway

Connecting line to Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway

Tewkesbury branch

Notes

- ↑ In its authorising Act of Parliament the company was referred to as the Gloucester and Cheltenham Railway.

- ↑ From Rake, part 1, page 146; Christiansen does not mention the date in either of the Regional History books (volume 7 and volume 13); Maggs gives 5 May in The Birmingham Gloucester Line.

- ↑ He is supposed to have seen a Norris locomotive climbing a 1 in 14 gradient, but later research suggests he merely saw a circular making that claim.

- ↑ It is remarkable that in a situation where tractive force was crucial, and dependent on adhesion weight, that a 4-2-0 design was favoured over an 0-6-0.

- ↑ Christiansen remarks that "The historian John Norris believes it is likely the branch was completed much earlier, being used to convey materials for construction of the main line, delivered to Tewkesbury by river craft.

- ↑ Sources differ about the number ordered and the timing of the orders. At the February 1839 shareholders' meeting it was stated that ten locomotives had been ordered from Norris of Philadelphia. Captain Moorsom explained that one such machine was to he tried upon the Lickey Inclined Plane by way of experiment, and at the manufacturer’s own risk and expense. Subject to these conditions, a provisional order would possibly be placed with Norris for ten or a dozen machines.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 P J Long and W V Awdry, The Birmingham and Gloucester Railway, Alan Sutton Publishing, Gloucester, 1987, ISBN 0 86299 329 6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Colin Maggs, The Birmingham Gloucester Line, Line One Publishing Limited, Cheltenham, 1986, ISBN 0-907036-10-4

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Herbert Rake, The South-western Extension of the Midland Railway: the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway: part 1, in the Railway Magazine, February 1904

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 E G Barnes, The Rise of the Midland Railway, 1844-1874, George Allen & Unwin Ltd, London, Chapter 5

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rex Christiansen, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 7: the West Midlands, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1973, ISBN 0 7153 6093 0

- ↑ Colin G Maggs, The Swindon to Gloucester Line, Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, Stroud, 1991, ISBN 0 7509 0000 8, pages 6 to 31

- ↑ David Bick, The Gloucester & Cheltenham Tramroad and the Leckhampton Quarry Lines, Oakwood Press, Usk, second edition 1987, ISBN 0 85361 336 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 John Gough, The Midland Railway: A Chronology, self-published, 1986, ISBN 0 9511310 0 1

- 1 2 Rex Christiansen, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 13: Thames and Severn, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1981, ISBN 0 7153 8004 4

- ↑ E T MacDermot, History of the Great Western Railway: volume I: 1833 - 1863, part 1, published by the Great Western Railway, London, 1927

- ↑ C G Maggs, The Bristol and Gloucester Railway and the Avon and Gloucestershire Railway, The Oakwood Press, Witney, second edition 1992, ISBN 0-85361-435-0

- ↑ Colin G Maggs, Gloucestershire Railways, Halsgrove (publisher), Wellington, 2010, ISBN 978 1 84114 913 4

- ↑ Ronalds, BF (Spring 2018). "Samuel Carter (1805-78): Early Railway Solicitor". Midland Railway Society Journal. 67: 11–13.

- ↑ John Boynton, The Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway, Mid England Books, Kidderminster, 2002, ISBN 0 954 0839 0 3

- ↑ Herbert Rake, The Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway, (part 2) in the Railway Magazine, February 1913

- ↑ Christian H Hewison, Locomotive Boiler Explosions, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1983, ISBN 0 7153 8305 1

- 1 2 3 4 M E Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in England Scotland and Wales—A Chronology, The Railway and Canal Historical Society, 2002

- 1 2 3 4 Col M H Cobb, The Railways of Great Britain -- A Historical Atlas, Ian Allan Publishing Limited, Shepperton, 2003, ISBN 07110 3003 0