Biracial and multiracial identity development

Biracial and multiracial identity development is described as a process across the life span that is based on internal and external forces such as individual family structure, cultural knowledge, physical appearance, geographic location, peer culture, opportunities for exploration, socio-historical context, etc.[1]

Biracial identity development includes self-identification A multiracial or biracial person is someone whose parents or ancestors are from different ethnic backgrounds. Over time many terms have been used to describe those that have a multiracial background. Some of the terms used in the past are considered insulting and offensive (mutt, mongrel, half breed); these terms were given because a person was not recognized by one specific race.

While multiracial identity development refers to the process of identity development of individuals who self-identify with multiple racial groups.[1] Multiracial individuals are defined as those whose parents are of two or more different and distinct federally recognized racial or ethnic groups.[2]

Background

Racial identity development defines an individual’s attitudes about self-identity, and directly affects the individual’s attitudes about other individuals both within their racial group(s) and others. Racial identity development often requires individuals to interact with concepts of inequality and racism that shape racial understandings in America.

Research on biracial and multiracial identity development has been influenced by previous research on racial and ethnic identity development. Most of this initial research is focused on black racial identity development (Cross, 1971)[3] and minority identity development (Morten and Atkinson, 1983)[4].

Like other identities, mixed race people have not been easily accepted in the United States. Numerous laws and practices prohibited interracial sex, marriage, and therefore, mixed race children. Below are some landmark moments in mixed race history.

Miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws or miscegenation laws enforced racial segregation through marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage. Certain communities also prohibit having sexual intercourse with a person of another race. These laws have since been changed in all U.S. states - interracial marriage is permitted. The last states to change these laws were South Carolina and Alabama. South Carolina made this change in 1998[5] and in 2000, Alabama became the last state in the United States to legalize interracial marriage.[6]

Biracial and multiracial categorization

"One Drop Rule"

The one-drop rule is a historical social and legal principle of racial classification in the United States. The one drop rule asserts that any person with one ancestor of African ancestry is considered to be Black. This idea was influenced by concerns of blacks passing as white in the U.S's deeply segregated south.[7] In this time, classification as Black rather than mulatto or mixed became prevalent. The "One Drop Rule" was used as a way to make people of color, especially multiracial Americans feel even more inferior and confused and was put into effect in the 1920s. No other country in the world at the time had thought of or implemented such a discriminatory and specific rule on its citizens[8] The One Drop Rule in a way was taking the Jim Crow Law to a new extreme level to make sure it stayed in power and was used as another extreme measure of social classification. Eventually, biracial and multiracial individuals challenged this assumption and created a new perspective of biracial identity and included the "biracial" option on the census.[9]

Hypodescent

The anthropological concept of hypodescent refers to the automatic assignment of children of a mixed union between different socioeconomic or ethnic groups to the group with the lower status. As Whites are historically a dominant social group, people of Black/White ancestry would be categorized as Black using this concept.[10]

The U.S. Census

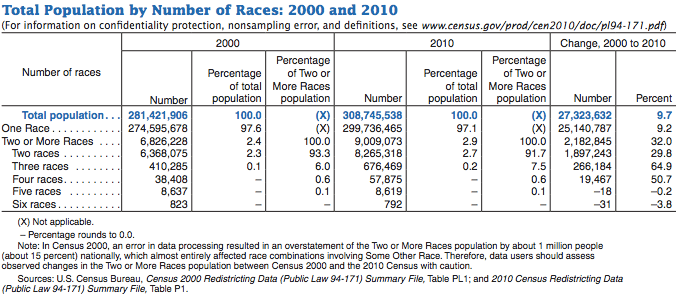

Before 2000 United States Census respondents were only able to select one race when submitting census data. This means that the census contained no statistical information regarding particular racial mixes and their frequency in the U.S. before this time.

Demographics

The population of biracial and multiracial people in the U.S. is growing. A comparison of data from the 2000 and 2010 United States Census indicates an overall population increase in individuals identifying with two or more races from 6.8 million people to 9 million people (US Census Data, 2010).[11] In examining specific race combinations, the data showed that, "people who reported White as well as Black or African American—a population that grew by over one million people, increasing by 134 percent—and people who reported White as well as Asian—a population that grew by about three-quarters of a million people, increasing by 87 percent" (US Census Data, 2010). In 2004, one in 40 persons in the United States self-identified as a multiracial, and by the year 2050, it is projected that as many as one in five Americans will claim a Multiracial background, and in turn, a Multiracial or Biracial identity (Lee & Bean, 2004).[12]

Early theories

When initial racial identity development research is applied to biracial and multiracial people, there are limitations, as they fail to recognize variance in developmental experiences that occur within racial groups (Gibbs, 1987).[13] This research assumes that individuals would choose to identify with, or choose to reject, one racial group over another dependent on life stage. Also, initial racial identity development research does not address real-life resolutions for people upholding multiple racial group identities (Poston, 1990).[14] These assumptions display the need for biracial and multiracial identity development that focuses on the unique aspects of the experience of biracial and multiracial identity development.

Stonequist's Marginal Person Model

American sociologist, Everett Stonequist was the first to publish research about the identity development of biracial individuals. His book, The Marginal Man: A Study in Personality and Culture Conflict (1937) discusses pathology in Black families through comparison of Black minority samples to White majority samples. Stonequist claimed that developing a biracial identity is a marginal experience, in which biracial people belong in two worlds and none all at the same time.[15] That they experience uncertainty and ambiguity, which can worsen problems people face identifying with their own racial groups and others (Gibbs, 1987).[13] A primary limitation of this model is that it is largely internal and focused on development within biracial individuals. The model does not discuss factors such as racism or racial hierarchy, which can worsen feelings of marginality for biracial persons. It does not address other functions of marginality that could also affect biracial identity development such as conflict between parental racial groups, or absence of influence from one racial identity (Hall, 2001).[16] The model fails to describe the experience of biracial people that exhibit characteristics of both races without conflict or feelings of marginality (Poston, 1990).[14]

Modern theories

To address the limitations of Stonequist’s Marginal Person Model, researchers have expanded biracial identity development research based on relevant and current understandings of biracial people. Most concepts of biracial identity development highlight the need for racial identity development across the lifespan. This type of development recognizes that identity is no more static a cultural entity than any other and that this fluidity of identity is shaped by the individual’s social circumstances and capital (Hall, 2001).[16]

Poston’s Biracial Identity Development Model

Walker S. Carlos Poston challenged Stonequist’s Marginal Man theory and claimed that existing models of minority identity development did not reflect the experiences of biracial and multiracial individuals.[17] Poston proposed the first model for the development of a healthy biracial and multiracial identity in 1990.[1] This model was developed from research on biracial individuals and information from relevant support groups. Rooted in counseling psychology, the model adapts Cross’ (1987)[18] concept of reference group orientation (RGO), which includes constructions of racial identity, esteem, and ideology. Poston’s model divided the biracial and multiracial identity development process into five distinct stages:

- Personal Identity: young children’s sense of self and personal identity is not linked to a racial or ethnic group.[17]

- Choice of Group Characterization:[1] an individual chooses a multicultural identity that includes both parents’ heritage groups or one parent’s racial heritage. This stage is based on personal factors (such as physical appearance and cultural knowledge) and environmental factors (such as perceived group status and social support.[17]

- Enmeshment/Denial: confusion and guilt over not being able to identify with all aspects of one’s heritage can lead to feelings of "anger, shame, and self-hatred". Resolving this guilt is necessary in order to move past this stage.[17]

- Appreciation: broadening of one’s racial group membership and knowledge about multiethnic heritage,[1] even though individuals may choose to identify with one group more than others.[17]

- Integration: recognition and appreciation of all racial and ethnic identities that make an individual unique.[1]

This model offers an alternative identity development process compared to the minority identity development models widely used in the student affairs profession.[17] However, it does not accurately address how societal racism affects the development process of people of color[17] and suggests that there is only one healthy identity outcome for biracial and multiracial individuals.[1]

Root’s Resolutions for Resolving Otherness

Maria Root’s Resolutions for Resolving Otherness (1990)[19] address the phenomenological experience of otherness in a biracial context and introduced a new identity group: multiracial.[17] With a footing in cultural psychology, Root suggests that the strongest conflict in biracial and multiracial identity development is the tension between racial components within one's self. She presents alternative resolutions for resolving ethnic identity based on research covering the racial hierarchy and history of the U.S., and the roles of family, age, or gender in the individual’s development.

Root's resolutions reflect a fluidity of identity formation; rejecting the linear progression of stages followed by Poston.[1] They include assessment of socio-cultural, political, and familial influences on biracial identity development. The four resolutions that biracial and multiracial individuals can use to positively cope with “otherness” are as follows:[17]

- Acceptance of the identity society assigns: an individual identifies with the group that others assume they belong to the most. This is often determined by one’s family ties and personal allegiance to the racial group (typically the minority group) that others assign.[17]

- Identification with both racial groups: an individual may be able to identify with both (or all) heritage groups. This is largely affected by societal support and one’s ability to remain resistance to other’s influences.[17]

- Identification with a single racial group: an individual chooses one racial group independently of external forces.

- Identification as a new racial group: an individual may choose to move fluidly throughout racial groups, but overall identifies with other biracial or multiracial people.[17]

Root's theory suggests that mixed race individuals "might self-identify in more than one way at the same time or move fluidity among a number of identities,".[17] These alternatives for resolving otherness are not mutually exclusive; no one resolution is better than another. As explained by Garbarini-Phillippe (2010), “any outcome or combination of outcomes reflect a healthy and positive development of mixed-race identity,”.[1]

Renn’s Ecological Theory of Mixed Race Identity Development

Dr. Kristen A. Renn was the first to look at multiracial identity development from an ecological lens.[17] Renn used Urie Bronfenbrenner's Person, Process, Context, Time (PPCT) model to determine which ecological factors were most influential on biracial and multiracial identity development.[20] Three dominant ecological factors emerged from Renn's research: physical appearance, cultural knowledge, and peer culture.

Physical appearance is the most influential factor and is described as how a biracial and multiracial person looks (i.e.: skin tone, hair texture, hair color, eye and nose shape, etc.). Cultural Knowledge is the second most important factor and can include the history that a multiracial individual knows about their various heritage groups, languages spoken, etc. Peer culture, the third most influential factor, can be described as support, acceptance, and/or resistance from peer groups. For example, racism among White students is an aspect of college peer culture that can impact an individual's perception of themself.

Renn conducted several qualitative studies across higher education institutions in the eastern and midwestern United States in 2000 and 2004. From the analysis of written responses, observations, focus groups, and archival sources, Renn identified five non-exclusive patterns of identity among multiracial college students.[17] The five identity patterns recognized by Renn include the following:

- Monoracial Identity: An individual identifies with one of the racial categories that makes up their heritage background. Forty-eight percent of Renn’s (2004) participants identified as having a monoracial identity.[20]

- Multiple Monoracial Identities: An individual identifies with two or more racial categories that make up their heritage background. Within a given time and place, both personal and contextual factors influence how an individual chooses to identify. Forty-eight percent of the participants also self-identified with this identity pattern.[17]

- Multiracial Identity: An individual identifies as part of a “multiracial” or “mixed” racial category, instead of identifying with one racial or other racial categories. According to Renn (2008), over eighty-nine percent of students from her 2004 study identified as part of a multiracial group.[17]

- Extraracial Identity: An individuals chooses to “opt out” of racial categorization or not to identify with one of the racial categories presented in the U.S. Census. One-fourth of the students that Renn (2004) interviewed identified with this category, and saw race as a social construct with no biological roots.[17]

- Situational Identity: An individual identifies differently depending on the situation or context, reinforcing the notion that racial identity is both fluid and contextual. Sixty-one percent of Renn’s (2004) participants identified in different ways depending on varying contexts.[20]

Like Root's resolutions, Renn's theory accounted for the fluidity of identity development. Each of the stages represented above are non-linear. Renn explained that some students from her studies self-identified with more than one identity pattern. This is why the total percentage of these identity patterns are more than 100 percent.[17] For example, a participant of European and African-American descent may have identified as multiracial initially, but also as Monoracial or Multiple Monoracial depending on the context of their environment or interactions with other individuals.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Garbarini-Philippe, Roberta (2010). "Perceptions, Representation, and Identity Development of Multiracial Students in American Higher Education" (PDF). Journal of Student Affairs at New York University. 6: 1–6.

- ↑ Viager, Ashley (2011). "Multiracial Identity Development: Understanding Choice of Racial Identity in Asian-White College Students" (PDF). Journal of the Indiana University Student Personnel Association: 38–45.

- ↑ Cross, W.E. (1971). "The Negro-toBlack conversion experience: Toward a psychology of Black liberation". Black World. 20: 13–27.

- ↑ Morten, G; Atkinson, D.R. (1983). "Minority identity development and preference for counselor race". Journal of Negro Education (52 ed.): 156–161.

- ↑ "A Groundbreaking Interracial Marriage". ABC News. 2009-01-08. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- ↑ "Alabama Interracial Marriage, Amendment 2 (2000) - Ballotpedia". ballotpedia.org. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- ↑ "Mixed Race America - Who Is Black? One Nation's Definition | Jefferson's Blood | FRONTLINE | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- ↑ Freeman, Harold P. (2003-03-01). "Commentary on the Meaning of Race in Science and Society". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 12 (3): 232s–236s. ISSN 1055-9965. PMID 12646516.

- ↑ Hud-Aleem, Raushanah; Countryman, Jacqueline (November 2008). "Biracial Identity Development and Recommendations in Therapy". Psychiatry (Edgmont). 5 (11): 37–44. ISSN 1550-5952. PMC 2695719. PMID 19724716.

- ↑ Banaji, Mahzarin (2011). "Evidence for Hypodescent and Racial Hierarchy in the Categorization and Perception of Biracial Individuals". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. doi:10.1037/a0021562.

- ↑ Jones, Nicholas (September 2012). "2010 Census Brief: The two or more races population" (PDF).

- ↑ Lee, J; Frank, D (2004). "America's Changing Color Lines: Immigration. Race/Ethnicity, and Multiracial Identification". Annual Review of Sociology. 30: 221–242. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110519.

- 1 2 Gibbs, Jewelle Taylor (1987). "Identity and Marginality: Issues in the treatment of biracial adolescents". American Journal of Orthopsychiatry (57(2)): 265–278.

- 1 2 Poston, W.S. Carlos (1990). "The Biracial Identity Development Model: A Needed Addition". Journal of Counseling and Development. 67: 152–155.

- ↑ Stonequist, Everett V. (1937). The Marginal Man: A Study in Personality and Culture Conflict. New York: Russell & Russell. ISBN 9780846202813.

- 1 2 Hall, R.E. (2001). "Identity Development Across the Lifespan: a biracial model". The Social Science Journal (38): 119–123.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Renn, Kristen A. (2008). "Research on biracial and multiracial identity development: Overview and synthesis". New Directions for Student Services. 2008 (123): 13–21. doi:10.1002/ss.282.

- ↑ Cross, W (1987). Phinney, J.S., ed. A two-factor theory of Black identity: implications for the study of identity development in minority children. Children's ethnic socialization. Pluralism and Development. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- ↑ Root, Maria (1990). Resolving "Other" Status: Identity Development of Biracial Individuals. Diversity and Complexity in Feminist Therapy. The Haworth Press. pp. 185–205.

- 1 2 3 Donahue, Lindsy; Juarez, Judy (n.d.). "Kristen Renn's Ecological Theory on Mixed-Race Identity Development" (PDF). Retrieved May 5, 2017.