Bilal ibn Rabah

| Bilal ibn Rabah بلال بن رباح | |

|---|---|

Titles: al-Habashi (التمار) and Sayyid al-Muʾaḏḏin  | |

| Born | March 5, 580 AD |

| Birthplace | Mecca, Hejaz |

| Ethnicity | Abyssinian (currently Eritrea/Ethiopia region)[1] |

| Known For | Being a loyal companion of Muhammad and the first muezzin in Islam[2][3] |

| Occupation | Secretary of Treasure of The Islamic State of Medina |

| Title | al-Habashi (التمار) and Sayyid al-Muʾaḏḏin |

| Died | March 2, 640 (aged 57) AD |

| Father | Rabah |

| Mother | Hamamah |

| Wife | Hind |

| Religion | Islam |

Bilal[lower-alpha 1] ibn Rabah (Arabic: بلال ابن رباح; 580–640 AD) also known as Bilal al-Habashi, Bilal ibn Riyah, and ibn Rabah), was one of the most trusted and loyal Sahabah (companions) of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He was born in Mecca and is considered as the first muezzin, chosen by Muhammad himself.[2][4][5][6] He was known for his beautiful voice with which he called people to their prayers. He died in 640, at the age of 57.

Birth and early life

Bilal ibn Rabah was born in Mecca in the Hejaz in the year 580 AD.[7] His father Rabah was an Arab slave from the clan of Banu Jumah while his mother, Hamamah, was a former princess of Abysinna (modern day Ethiopia) who was captured after the event of Amul-Fill (the attempt to destroy the Ka'aba) and put into slavery. Being born into slavery, Bilal had no other option but to work for his master, Umayyah ibn Khalaf. Through hard work, Bilal became recognised as a good slave and was entrusted with the keys to the Idols of Arabia. However, racism and sociopolitical statutes of Arabia prevented Bilal from achieving a lofty position in society.[7]

Bilal's appearance

Muhammad Abdul-Rauf in his book, Bilal ibn Rabah, states,

- "He [Bilal] was of a handsome and impressive stature, dark brown complexion with sparkling eyes, a fine nose and bright skin. He was also gifted with a deep, melodious, resonant voice. He wore a beard which was thin on both cheeks. He was endowed with great wisdom and a sense of dignity and self esteem."[8]

Similarly, William Muir in his book, The Life of Muhammad, states,

- "He (Bilal) was tall, dark, and with African feature and bushy hair."[9]

Muir also states that noble members of the Quraysh despised Bilal and called him ibn Sauda (son of the black woman).[9]

Conversion to Islam

When Muhammad announced his prophethood and started to preach the message of Islam, Bilal renounced idol worship, becoming one of the earliest converts to the faith.[10]

Persecution of Bilal

When Bilal's master, Umayyah ibn Khalaf, found out, he began to torture Bilal.[7] At the instigation of Abu Jahl, Umayyah bound Bilal and had him dragged around Mecca[10] as children mocked him.[10] Bilal refused to renounce Islam, instead repeating "Ahad Ahad" (God is absolute/one).[10] Incensed at Bilal's refusal, Umayyah ordered that Bilal be whipped and beaten while spread-eagled upon the Arabian sands under the desert sun, his limbs bound to stakes. When Bilal still refused to recant, Umayyah ordered that a hot boulder be placed on Bilal's chest.[7] However, Bilal remained firm in belief and continued to say "Ahad Ahad".[7] News of this slave reached some of Muhammad's companions, who informed the prophet. Muhammad sent Abu Bakr to negotiate for the emancipation of Bilal in exchange for three of Abu Bakr's slaves (a pagan male and his wife and daughter).[7][10][11][12]

Treasury

Bilal rose to prominence in the Islamic State of Medina, as Muhammad appointed him minister of the Bayt al-Mal (treasury).[13][13] In this capacity, Bilal distributed funds to widows, orphans, wayfarers, and others who could not support themselves.[13][14]

Adhan

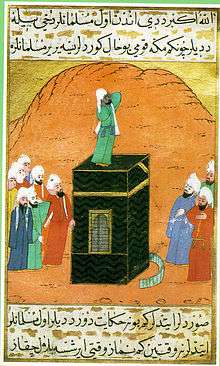

Muhammad chose Bilal as the first muezzin.[15]

Sunni view

Sunnis believed that Muhammad specifically chose Bilal to become the Muezzin (caller to prayer) of Islam.[14] He personally taught Bilal how to call the Muslims to prayer.[14] However, other Sunni traditions suggest that a companion suggested to Muhammad that they should blow a trumpet or ring a bell in order to alert the Muslims before the time of each prayer.[14] According to the Sunni traditions Muhammad did not accept this suggestion because he did not want to adopt the Jewish or Christian customs.[14] One day, Abdullah ibn Ziyad, a citizen of Yathrib (Medina), came to see Muhammad.[14] Abdullah ibn Ziyad explained to him that while he was half-awake or half-asleep, a man appeared before him in his dream and told him that the human voice ought to be used to call the Muslims to prayer.[14] In addition, the man also taught Abdullah the Adhan along with the manner of saying it.[14] The Sunni historians state that Muhammad was pleased with the idea and adopted it.[14] After adopting the Adhan, Muhammad called Bilal and taught the Adhan to him.[14]

Shia view

Shias, on the other hand, do not accept Abdullah ibn Ziyad’s story.[14] They state that the Adhan was revealed to Muhammad just as the Qur'an al-Majid was revealed to him.[14] Shias believe that the Adhan could not be left to the dreams or reveries.[14] Furthermore, Sayed Ali Asgher Razwy states, "If the Prophet could teach the Muslims how to perform prostrations, and how, when, and what to say in each prayer, he could also teach them how and when to alert others before the time for each prayer." According to the Shia traditions, the angel who taught Muhammad how to perform ablutions preparatory to prayers and how to perform prayers also taught him the Adhan.[14]

Military campaigns during Muhammad's era

He participated in the Battle of Badr. Muhammad's forces included Ali ibn Abi Talib, Hamza ibn Abd al-Muttalib, Ammar ibn Yasir, Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, Abu Bakr, Umar, Mus`ab ibn `Umair, and Az-Zubair bin Al-'Awwam, The Muslims also brought seventy camels and two horses, meaning that they either had to walk or fit three to four men per camel.[16] However, many early Muslim sources indicate that no serious fighting was expected,[17] and the future Caliph Uthman stayed behind to care for his sick wife Ruqayyah, the daughter of Muhammad.[18] Salman the Persian also could not join the battle, as he was still not a free man.[19][20]

After Muhammad

Sunni view

In the Sīrat Abī Bakr Al-Ṣiddīq that compiled many narrations and compiled historical circumstances regarding the rule of Caliph Abu Bakr, Bilal accompanied the Muslim armies, under the commands of Said ibn Aamir al-Jumahi, to Syria.[21]

Shia view

After Muhammad died in 632 AD, Bilal was one of the people who did not give bay'ah (the oath of allegiance) to Abu Bakr.[3][22][23][24] It is documented that when Bilal did not give bay'ah to Abu Bakr, Umar ibn al-Khattab grabbed Bilal by his clothes and said,

Is this the reward of Abu Bakr; he emancipated you and you are now refusing to pay allegiance to him?[3]

To which Bilal replied,

If Abu Bakr had emancipated me for the pleasure of Allah, then let him leave me alone for Allah; and if he had emancipated me for his service, then I am ready to render him the services required. But I am not going to pay allegiance to a person whom the Messenger of God had not appointed as his caliph.[3]

Similarly, al-Isti'ab, a Sunni source, states that Bilal told Abu Bakr:

If you have emancipated me for yourself, then make me a captive again; but if you had emancipated me for Allah, then let me go in the way of Allah.

This was said when Bilal wanted to go for Jihad. Abu Bakr then let him go."[3][25]

The following is a poem by Bilal on his refusal to give Abu Bakr bay'ah:

- By Allah! I did not turn towards Abu Bakr,

- If Allah had not protected me,

- hyena would have stood on my limbs.

- Allah has bestowed on me good

- and honoured me,

- Surely there is vast good with Allah.

- You will not find me following an innovator,

- Because I am not an innovator, as they are.[3]

Being exiled from Medina by Umar and Abu Bakr, Bilal migrated to Syria.[3]

Abu Ja'far al-Tusi, a Shia scholar, has also stated in lkhtiyar al-Rijal that Bilal refused to pay allegiance to Abu Bakr.[3]

Sufism

A Sufi poet whose, works originated from the Mughal Empire, named Purnam Allahabadi, composed a Qawwali in which he mentioned how time had stopped when some companions blocked Bilal from delivering the Adhan (which he had seen in his dream), and appealed that it was incorrect.[26] Because the companion Bilal was of an Abyssinian origin, he could not pronounce the letter "Sh" (Arabic: Shin ش ). A hadith of Muhammad reports that he said, "The 'seen' of Bilal is 'sheen' in the hearing of Allah," meaning God does not look at the external but appreciates the purity of heart.[27]

Death

Bilal's death is disputed by historians. Some believe that he died in 638 AD, while others believe he died in 642. It is said that Bilal was 63 years old when he died.

The Sunni scholar al-Suyuti in his Tarikh al-khulafa wrote: "He (Bilal) died in Damascus in 17 or 18 AH, but some say 20 AH, or even 21 AH when he was just over sixty years old. Some said he died in Medina, but that is wrong. That is how it is in al-Isabah and other works such as the Tahdhib of an-Nawawi."[28]

When Bilal's wife realized that death was approaching Bilal, she became sorrowful.[29] It is documented that she cried and said, "What a painful affliction!"[29] However, Bilal objected his wife's opinion by stating, "On the contrary, what a happy occasion! Tomorrow I will meet my beloved Muhammad and his host (hizb)!"[29]

Descendants and legacy

The descendants of Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi are said to have migrated to the land of Ethiopia in Africa.[30]

Though there are some disagreements concerning the hard facts of Bilal's life and death, his importance on a number of levels is incontestable. Muezzins, especially those in Turkey and Africa, have traditionally venerated the original practitioner of their profession. The story of Bilal is the most frequently cited demonstration of Islam's views of measure people not by their nationality nor social status nor race, but measuring people by their Taqwah (piety). Which is demonstrated in Muhammad's The Farewell Sermon in Mina:

O people! Your Lord is one Lord, and you all share the same father. There is no preference for Arabs over non-Arabs, nor for non-Arabs over Arabs. Neither is their preference for white people over black people, nor for black people over white people. Preference is only through righteousness.

In 1874, Edward Wilmot Blyden, a former slave of African descent, wrote:

The eloquent Adzan or Call to Prayer, which to this day summons at the same hours millions of the human race to their devotions, was first uttered by a Negro, Bilal by name, whom Mohammed, in obedience to a dream, appointed the first Muezzin or Crier. And it has been remarked that even Alexander the Great is in Asia an unknown personage by the side of this honoured Negro.[33]

See also

- List of non-Arab Sahabah

- Zayd ibn Harithah

- Keita Dynasty

- List of expeditions of Muhammad

- Bilal: A New Breed of Hero, a 2015 animated film about Bilal's life.

Notes

- ↑

- Bilal stands for "wetting, moistening" in Arabic.

References

- ↑ Coughlin, Kathryn M. (2006). "Ethiopia". Muslim Cultures Today: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313323867. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- 1 2 "Slavery in Islam." BBC News. BBC, 2009. Web. 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Riz̤vī, Sayyid Sa'eed Ak̲h̲tar. Slavery: From Islamic & Christian Perspectives. Richmond, British Columbia: Vancouver Islamic Educational Foundation, 1988. Print. ISBN 0-920675-07-7 Pg. 35-36

- ↑ Ludwig W. Adamec (2009), Historical Dictionary of Islam, p.68. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810861615.

- ↑ Robinson, David. Muslim Societies in African History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004. Print.

- ↑ Levtzion, Nehemia, and Randall Lee Pouwels. The History of Islam in Africa. South Africa: Ohio UP, 2000. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Janeh, Sabarr. Learning from the Life of Prophet Muhammad (SAW): Peace and Blessing of God Be upon Him. Milton Keynes: AuthorHouse, 2010. Print. ISBN 1467899666 Pgs. 235-238

- ↑ Abdul-Rauf, Muhammad. Bilāl Ibn Rabāh: A Leading Companion of The Prophet Muhammad (SAW). Indianapolis, Indiana: American Trust Publications, 1977. Print. ISBN 0892590084 Pg.5

- 1 2 Muir, Sir William. The Life of Mohammad From Original Sources. Edinburgh: J. Grant, 1923. Print. ISBN 0404563066 Pg. 59

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sodiq, Yushau. Insider's Guide to Islam. Bloomington, Indiana: Trafford, 2011. Print. ISBN 1466924160 Pg. 23

- ↑ , Ibn Hisham, Sirah, V. 1, p. 339-340

- ↑ Ibn Sa’d, Tabaqat, V. 3, p. 232

- 1 2 3 Charbonneau, Joshua (Mateen). The Suffering of the Ahl-ul-bayt and Their Followers (Shi'a) throughout History. Washington, D.C.: J. M. Charbonneau, 2012. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Razwy, Ali A. A Restatement of the History of Islam & Muslims 570 to 661 CE. Stanmore, Middlesex, U.K.: World Federation of K S I Muslim Communities Islamic Centre, 1997. Print. Pg. 553

- ↑ Ludwig W. Adamec (2009), Historical Dictionary of Islam, p.68. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810861615. Quote: "Bilal, ..., was the first muezzin."

- ↑ Lings, pp. 138–139

- ↑ "Sahih al-Bukhari: Volume 5, Book 59, Number 287". Usc.edu. Archived from the original on 16 August 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ "Sahih al-Bukhari: Volume 4, Book 53, Number 359". Usc.edu. Archived from the original on July 20, 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ "Witness-pioneer.org". Witness-pioneer.org. 16 September 2002. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ "Sahih al-Bukhari: Volume 5, Book 59, Number 286". Usc.edu. Archived from the original on 16 August 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ Dr. Ali Muhammad As-Sallaabee The Biography of Abu Bakr As-Sideeq. Riyadh: Maktaba Dar-us-Salaam, 2007. Print. ISBN 9960-9849-1-5

- ↑ Shustari, Nurullah, Majalisu'1-Mu'minin (Tehran, 1268 AH) p. 54; and also see Ibn Sa'd, op. cit., vol. III:1, pg. 169.

- ↑ Ahmed, A.K. The Hidden Truth About Karbala. Ed. Abdullah Al-shahin. Qum, Iran: Ansariyan Publications, n.d. Print. ISBN 978-964-438-921-4 Pg. 307

- ↑ Meri, Josef W., and Jere L. Bacharach. Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge, 2006. Print. ISBN 0415966914 Pg. 109

- ↑ Abdullah, Ysuf. al-Isti'ab. Print. Pg.150

- ↑ http://www.hamzashad.com/bhar-do-jholi/

- ↑ Bilal Ibn Rabah Al-Habashi

- ↑ Rijal: Narrators of the Muwatta of Imam Muhammad." Bogvaerker. N.p., 08 Jan. 2005. Web. 2013.

- 1 2 3 Qušairī, Abd-al-Karīm Ibn-H̲awāzin Al-, and Abu'l-Qasim al-Qushayri. al-Qushayri's Epistle on Sufism: al-Risala al-Qushayriyya Fi 'ilm al-Tasawwuf. Trans. Alexander D. Knysh. Lebanon: Garnet & Ithaca Press, 2007. Print. ISBN 1859641865 Pg.313

- ↑ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. The Heart of Islam: Enduring Values for Humanity. New York, New York: HarperCollins, 2009. Print. ISBN 0061746606 Pg. 92

- ↑ Zawadi, Bassam, and Mansur Ahmed. "Rebuttal to Answering Islam's Article 'Mohammed Claimed To Be A Warner Only For Arabia'" Call-To-Monotheism. N.p., n.d. Web. 2013.

- ↑ Musnad Ahmad Hadith. 22391

- ↑ "Mohammedanism and The Negro Race." Fraser's Magazine July Dec. 1875: 598-615. Print.

Further reading

- H.M. Ashtiyani. Bilâl d’Afrique, le muezzin du Prophète, Montréal, Abbas Ahmad al-Bostani, la Cité du Savoir, 1999 ISBN 2-9804196-4-8 (in French)

- İbn Sa'd. et-Tabakâtü'l-Kübrâ, Beyrut 1960, III, s. 232

- Avnu'l-Ma'bud. Şerh Ebû Dâvud, III,185, İbn Mâce, Ezan, 1, 3

- А. Али-заде. Билал аль-Хабаши // Исламский энциклопедический словарь. – М.: Издательский дом Ансар, 2007. — 400 с. ISBN 5-98443-025-8 (in Russian)

External links

- Medieval Islamic Civilization

- Omar H. Ali, "Arabian Peninsula," Schomburg Center, The New York Public Library

- al-islam.org – Slaves in the History of Islam

- The First Muezzin