Benty Grange hanging bowl

| Benty Grange hanging bowl | |

|---|---|

| Material | Bronze, enamel |

| Discovered |

1848 Benty Grange farm, Monyash, Derbyshire 53°10′30″N 1°46′59″W / 53.174895°N 1.782923°W |

| Discovered by | Thomas Bateman |

| Present location | Weston Park Museum, Sheffield; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford |

| Registration | J93.1190; AN1893.276 |

The Benty Grange hanging bowl is a fragmentary Anglo-Saxon artefact from the 7th century AD. All that remains are two escutcheons; a third disintegrated soon after excavation, and no longer survives. The escutcheons were found in 1848, alongside the better-known Benty Grange helmet, by the antiquary Thomas Bateman in a tumulus at the Benty Grange farm in the English county of Derbyshire. They were undoubtedly buried as part of an entire hanging bowl, placed in what appears to have been the burial mound of a high-status warrior.

What remains of one escutcheon belongs to Museums Sheffield and in 2018 was displayed at Weston Park Museum.[1] The other is held by the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford; as of 2018 it is not on display.[2]

Description

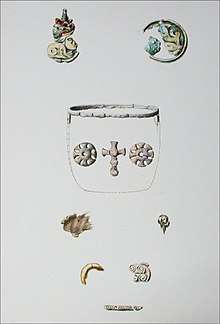

The two surviving escutcheons are made of enamelled bronze and are 40 mm (1.6 in) in diameter.[3] They have the same design and plain frames, parts of which survive.[3] Both escutcheons are fragmentary; enough survives of each for the design to be reconstructed,[3] and, because of overlapping segments, for it to be certain that they represent two distinct pieces.[4] Whether they are hook escutcheons, associated with the suspension hooks on the exterior of the bowl, or basal discs, placed at the base of the interior, is uncertain, but a ring on the back of one fragment suggests an association with the suspension chains, and a contemporary watercolour by Llewellynn Jewitt seems to show that a hook may have been present at excavation.[3] The decomposed enamel background appears yellow to the eye,[5] as it did when excavated.[6][7][8] A red-yellow colour scheme has also been suggested,[9][10] but on minimal and possibly incorrect evidence.[5] As sampling of the enamel was not permitted when the Sheffield escutcheon was analysed at the museum in 1968, however, the all-yellow hypothesis is not definitive.[11]

The reconstructed design shows three "ribbon-style fish or dolphin-like creatures", each biting the tail of the animal ahead of it.[3] The bodies are yellow like the background, and defined by their outlines.[4] They are limbless, the tails curled in a circle, and the jaws both long and curved; where the tails should pass through the jaws of the animals behind, gaps appear, creating slight separations between segments of tail.[3] Each animal has a small eye shaped like a pointed oval.[3] The outer borders of the discs, the plain frames, and the contours and eyes of the animals, are all tinned or silvered.[3]

Surviving records of the third escutcheon indicate that it was of a different style and size.[3][4] Drawings by Bateman and Jewitt show it with a scroll pattern and small piece of frame.[4][6][12] It appears to have been about half the size of the other two, and may have originally been placed at the bottom of the hanging bowl.[3]

The escutcheons were undoubtedly part of an entire hanging bowl when buried.[3] Nothing else survives.[3] The mass of corroded chainwork discovered six feet away, which survives only in illustrations by Jewitt and descriptions by Bateman,[13][14] is unlikely to be related; although a large and intricate chain was found with a cauldron from Sutton Hoo, the Benty Grange chains appear dissimilar.[15] They were also likely too heavy to have been used to suspend the hanging bowl.[15]

Parallels

The animal designs on the Benty Grange hanging bowl are paralleled by designs on other escutcheons, and even more closely by designs on medieval illuminated manuscripts.[9][16] Three escutcheons from a hanging bowl found in Faversham show animals that also look like dolphins,[17][18][19] but with more developed bodies;[16] a better parallel is with a disc found near the Lullingstone hanging bowl that is also decorated with dolphin-like creatures.[20]

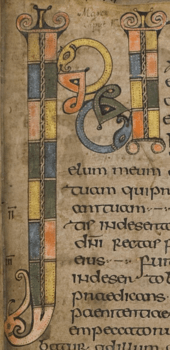

Despite the similarities with other escutcheon and disc designs, several manuscript illustrations are more closely related to the Benty Grange designs.[16] Bateman remarked on this as early as 1861, "shrewdly" as it turned out,[21] noting that similar patterns were used in "several manuscripts of the VIIth Century, for the purpose of decorating the initial letters."[8] In particular, the mid-seventh-century Durham Gospel Fragment contains two similar fish-like motifs contained within the lateral stroke of the INI monogram that introduces the Gospel of Mark.[4]

Discovery

The hanging bowl was discovered on 3 May 1848 during an excavation on the Benty Grange farm in Derbyshire,[22] in what is now the Peak District National Park.[23] It was found by Thomas Bateman, an archaeologist and antiquarian who was nicknamed "The Barrow Knight" for his excavation of more than 500 barrows.[24][25] Bateman described Benty Grange as "a high and bleak situation";[22] its barrow, which still survives, is prominently located by a major Roman road, now the A515, possibly in order to display the burial to passing travellers.[26] It may have also been designed to share the skyline with two other nearby monuments, Arbor Low stone circle and Gib Hill barrow.[26] The Benty Grange barrow comprises a circular central mound approximately 15 m (49 ft) in diameter and 0.6 m (2 ft) high, an encircling fosse about 1 m (3.3 ft) wide and 0.3 m (1 ft) deep, and outer penannular banks around 3 m (10 ft) wide and 0.2 m (0.66 ft) high.[27] The entire structure measures approximately 23 by 22 m (75 by 72 ft).[27]

Unnoted in Bateman's account is that he was likely not the first person to dig up the grave.[28] The fact that the objects were found in two clusters separated by six feet, and that other objects that normally accompany a helmet were absent, such as a sword and shield, suggests that the grave had previously been looted.[28] Being so large it may alternatively or additionally have contained two inhumations, only one of which was discovered by Bateman.[27]

The Benty Grange barrow was designated a scheduled monument on 23 October 1970.[27] The list entry notes that "[a]lthough the centre of Benty Grange [barrow] has been partially disturbed by excavation, the monument is otherwise undisturbed and retains significant archaeological remains."[27] It goes on to note that further excavation would yield new information.[27] The nearby farm was renovated between 2012 and 2014;[29][30] as of 2018 it is rented out as a holiday cottage.[31]

References

- ↑ Museums Sheffield escutcheon.

- ↑ Ashmolean Museum.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 119.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bruce-Mitford 1974, p. 250 n.5.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 2005, pp. 77, 119.

- 1 2 Bateman 1849, p. 277.

- ↑ Bateman 1855, p. 160.

- 1 2 Bateman 1861, p. 29.

- 1 2 Henry 1936, p. 236.

- ↑ Haseloff 1990, p. 162.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 77.

- ↑ Bateman 1861, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Museums Sheffield chainwork 1.

- ↑ Museums Sheffield chainwork 2.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1974, p. 250 n.6.

- 1 2 3 Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 120.

- ↑ British Museum Faversham 1.

- ↑ British Museum Faversham 2.

- ↑ British Museum Faversham 3.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 2005, pp. 72, 120, 175, 428.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford 1974, pp. 224–225.

- 1 2 Bateman 1861, p. 28.

- ↑ Lester 1987, p. 34.

- ↑ Bateman 1861, p. vi.

- ↑ Howarth 1899, p. v.

- 1 2 Brown 2017, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Historic England Benty Grange.

- 1 2 Bruce-Mitford 1974, p. 229.

- ↑ Peak District Applications 2012.

- ↑ BentyGrange Twitter 2014.

- ↑ Peak Venues Benty Grange.

Bibliography

- Allen, John Romilly (1898). "Metal Bowls of the Late-Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Periods". Archaeologia. LVI: 39–56. doi:10.1017/s0261340900003842.

- Bateman, Thomas (1849). "Description of the Contents of a Saxon Barrow". The Journal of the British Archaeological Association. IV (3): 276–279. doi:10.1080/00681288.1848.11886866.

- Bateman, Thomas (1855). A Descriptive Catalogue of the Antiquities and Miscellaneous Objects Preserved in the Museum of Thomas Bateman, at Lomberdale House, Derbyshire. Bakewell: James Gratton.

- Bateman, Thomas (1861). Ten Years' Digging in Celtic and Saxon Grave Hills, in the counties of Derby, Stafford, and York, from 1848 to 1858; with notices of some former discoveries, hitherto unpublished, and remarks on the crania and pottery from the mounds. London: John Russell Smith. pp. 28–33.

- Benty Grange [@BentyGrange] (22 August 2014). "We are proud to open the doors to Benty Grange to our first guests. We couldn't have done it without @PeakVenues . THANKS" (Tweet). Retrieved 10 February 2018 – via Twitter.

- "Benty Grange hlaew, Monyash – 1013767". Historic England. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- "Benty Grange – Barn Conversion – Peak Venues". Peak Venues. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- Brown, Antony (October 2017). "Dowlow Quarry ROMP Environmental Statement Appendix 10.2: Setting Assessment" (PDF). ARS Ltd Reports. 2017 (82).

- Brown, David (1981). "Swastika Patterns". In Evison, Vera Ivy. Angles, Saxons, and Jutes: Essays Presented to J. N. L. Myres. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 227–2410. ISBN 978-0-19-813402-2.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1974). Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology: Sutton Hoo and Other Discoveries. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN 978-0-575-01704-7.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1987). "Ireland and the Hanging Bowls—A Review". In Ryan, Michael. Ireland and Insular Art, A.D. 500–1200: Proceedings of a Conference at University College Cork, 31 October-3 November 1985. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. pp. 30–39. ISBN 978-0-901714-54-1.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (2005). Taylor, Robin J., ed. A Corpus of Late Celtic Hanging-Bowls with An Account of the Bowls Found in Scandinavia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-813410-7.

- "Escutcheon of hanging bowl". Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology. University of Oxford. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Fowler, Elizabeth (1968). "Hanging Bowls". In Coles, John Morton & Simpson, Derek Douglas Alexander. Studies in Ancient Europe: Essays Presented to Stuart Piggott. Leicester: Leicester University Press. pp. 287–310.

- "Fragments of enamelled escutcheon from Benty Grange". I Dig Sheffield. Museums Sheffield. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- "hanging bowl". The British Museum Collection Online. The British Museum. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "hanging bowl". The British Museum Collection Online. The British Museum. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "hanging bowl". The British Museum Collection Online. The British Museum. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Haseloff, Günther (1958). Translated by de Paor, Liam. "Fragments of a Hanging-Bowl from Bekesbourne, Kent, and Some Ornamental Problems" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. 2: 72–103.

- Haseloff, Günther (1990). Email im frühen Mittelalter: Frühchristiliche Kunst von der Spätantike bis zu den Karolingern. Marburg: Hitzeroth. ISBN 978-3-89398-020-8. (in German)

- Henry, Françoise (31 December 1936). "Hanging Bowls". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 7th series. VI (II): 209–246. JSTOR 25513828.

- Howarth, Elijah (1899). Catalogue of the Bateman Collection of Antiquities in the Sheffield Public Museum. London: Dulau and Co.

- Kendrick, T. D. (June 1932). "British Hanging Bowls". Antiquity. VI (22): 161–184. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00006700.

- Lester, Geoff (Fall 1987). "The Anglo-Saxon Helmet from Benty Grange, Derbyshire" (PDF). Old English Newsletter. 21 (1): 34–35. ISSN 0030-1973.

- Longley, David (1975). "Hanging-Bowls, Penannular Brooches and the Anglo-Saxon Connexion". British Archaeological Reports. 22.

- Ozanne, Audrey (1962–1963). "The Peak Dwellers" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. 6–7: 15–52.

- Smith, Reginald Allender (1907–1909). "Notes on Bronze Hanging-Bowls and Enamelled Mounts". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of London. 2nd series. XXII: 63–86.

- Speake, George (1980). Anglo-Saxon Animal Art. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-813194-6.

- Vierck, Hayo (December 1970). "Cortina Tripodis. Zu Aufhängung und Gebrauch subrömischer Hängebecken aus Britannien und Irland". Frühmittelalterliche Studien. 4: 8–52. doi:10.1515/9783110242041.8 (inactive 2018-08-19).

(in German)

- "Watercolour Showing Fragments of Metal Chainwork". I Dig Sheffield. Museums Sheffield. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Watercolour Showing Fragments of Metal Chainwork". I Dig Sheffield. Museums Sheffield. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Weekly List of Applications Validated by the Authority: Applications validated between 18/072012 – 24/07/2012" (PDF). Peak District National Park Authority. Retrieved 10 February 2018.