Benghazi under Italy

Benghazi under Italy was the period of time during the Italian colonization of Libya for the port-city of Benghazi in Italian Cyrenaica.

History

On October 19, 1911 the Ottoman city of Benghazi was occupied by the Italians during the Italo-Turkish War[1].

Even if Benghazi city accepted the Italians and some members of the local community collaborated with the Italian government, in the interior nearly half the local population of Cyrenaica under the leadership of Omar Mukhtar resisted the Italian occupation. Many local arabs -under the Senussi leadership- suffered oppression, particularly from the fascist dictator Mussolini in the late 1920s.

In the early 1930s, the revolt was over and the Italians—under governor Italo Balbo—started attempts to assimilate the local population with pacifying policies: a number of new villages for local Cyrenaicans were created with health services and schools.

Additionally Cyrenaica was populated by more than 20,000 Italian colonists in the late 1930s, mainly around the coast of Benghazi. Benghazi population was made up of more than 35 per cent of Italians in 1939[2].

In 1941 Italian Benghazi -according to estimates of the Italian government[3]- reached a temporary population of nearly 80,000 inhabitants, due to the arrival of many Italians from Cyrenaica who took refuge from the British army attacks during WWII. As a consequence Tripoli was in that year -for the first time since the Arab conquest in 643 AD- a city mostly Christian.

Benghazi was heavily bombed during World War II (more than one thousand times) and -when the British finally occupied the city in December 1942- nearly 85% of the city was damaged or destroyed.

Characteristics

Benghazi [4] was located in northern Italian Libya, in Cyrenaica. It was the administrative center of the Italian Benghazi Province, on the Mediterranean coast.

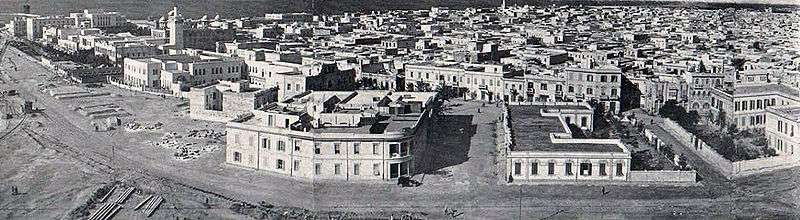

Indeed the Italians conquered from the Ottomans in 1911 a region in coastal Cyrenaica that was very poor and underdeveloped: it had no asphalted road, no telegraph services, no sewages system and no hospitals (in 1874 Benghazi had been depopulated by the bubonic plague). In the next twenty years they built all these infrastructures and by the early 1930s a new port and a railways station were created in Benghazi.

In the 1920s in the Benghazi province was created a railway between Benghazi and Barce: a 750 mm (2 ft 5 1⁄2 in) (later 950 mm) gauge railway was built east from Benghazi; the main route was 110 km long to Marj and was opened in stages between 1911 and 1927. Benghazi also had a 56 km branch to Suluq opened in 1926.[5]

In the late 1930s in the Benghazi province were settled thousands of Italians as farmers in special villages.[6] Most of the Italians were concentrated in the city of Benghazi, where they were in 1939 nearly one third of the population.

Architecture

Benghazi came under Italian rule in the early part of the 20th century: some examples of Italianate, as well as modernist colonial architecture from this period remain today. Under the governorships of Generals Ernesto Mombelli and Attilio Teruzzi in the 1920s, the buildings commissioned in Benghazi had an eclectic architectural language that embodied a Western conception of Eastern architecture.

An example of this is the Municipal palace built in 1924, which stands in Maydan al-Hurriya (Freedom Square). The building combines Moorish arches with Italianate motifs on the facade. Italians even did the first architectural plan of Benghazi.[7] in the 1930s, with a new railway station and promenade.

The heart of the Italian city was the Piazza del Re, formerly Piazza del Sole, with the central part dedicated to a nice garden. On it overlooked the Palazzo del Governo, a Moorish-style building, formerly the seat of the Cyrenaic Parliament, which housed the Library and the Civil Court, and other noteworthy architectures. The Corso Italia, lined with palm trees, flowed into the square: it was the most important artery of the city and led to the Railways station; on it stood the main facade of the Palazzo del Governatore (1928-34), designed by Alpago Novello, Cabiati and Ferrazza, overlooking Piazza XXVIII Ottobre; here were lined various buildings such as the Elementary and Middle Schools and the Sports Club. Piazza del Re was connected, via the axis of via Roma and via general Briccola, to the Piazza del Municipio, located inside the ancient city, in which stood the Moorish-style Town Hall. V. Santoianni[8]

Many buildings and streets were built in the late 1930s, making "Bengasi" a town that looked like a typical Italian city [9]. The largest colonial building from this Italian period is the Benghazi Cathedral in Maydan El Catedraeya (Cathedral Square), which was built in the 1920s and has two large distinct domes.[10]

Notes

- ↑ Occupation of Benghazi by the Italian troops (p. 79-95)

- ↑ Video of Italian colonists going to Libya from Venice in 1938

- ↑ Istituto Agricolo Coloniale (Firenze).Ministero degli Esteri, 1946

- ↑ Italian Benghazi

- ↑ History of railways in colonial Libya (in Italian)

- ↑ Italians in new villages in Cyrenaica

- ↑ "Italian Urban Plan of Benghazi".

- ↑ Vittorio Santoianni."Il Razionalismo nelle colonie italiane 1928-1943. La 'nuova architettura' delle Terre d’Oltremare" Section: Bengasi (p. 59)

- ↑ Via Briccola

- ↑ McLaren, Brian L. (2006). Architecture and Tourism in Italian Colonial Libya – An Ambivalent Modernism. University of Washington Press (Seattle, Washington). p. 158. ISBN 978-0-295-98542-8.

Bibliography

- Chapin Metz, Hellen. Libya: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1987

- Pagano, Giovanni. Architettura e città durante il fascismo. Editori Laterza. Roma, 1990

- Santoianni, Vittorio. Il Razionalismo nelle colonie italiane 1928-1943.La «nuova architettura» delle Terre d’Oltremare. Ed. Universita' Federico II. Napoli, 2008 ()

- Sean Anderson. "The Light and the Line: Florestano Di Fausto and the Politics of Mediterraneità". California Italian Studies. University of California, 2010.