Beit Jimal

| Beit Jimal بيت جمال / الحكمه | |

|---|---|

Beit Jimal - general view | |

Beit Jimal | |

| Coordinates: 31°43′30″N 34°58′35″E / 31.72500°N 34.97639°ECoordinates: 31°43′30″N 34°58′35″E / 31.72500°N 34.97639°E | |

| Grid position | 147/125 PAL |

Beit Jimal (or Beit Jamal; Hebrew: בית ג'מאל; Arabic: بيت جمال / الحكمه)[1] is a Catholic monastery run by Salesian monks near Beit Shemesh, Israel. The monks identify the site with the Byzantine town of Caphargamala, and believe that a cave there may have been the tomb of St. Stephen or to have conserved his relics.[2]

Geography

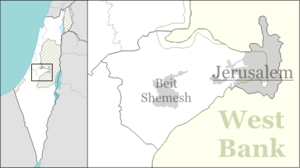

The Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine in 1883 described Beit Jimal (alt. sp. Beit el Jemâl) as possessing a natural spring three-quarters of a mile to the east, while to the south were caves.[3] Natural brushwood consisting mainly of oak, buckthorn and mastic trees can be seen on the adjacent hill country lying to its south. To the east of Beit Jimal at a few hours' walking distance was the Arab village, Bayt Nattif. The monastery is located in the Judean hills next to the city of Beit Shemesh.

History

Ancient cisterns have been found here.[4] In Arabic and Hebrew the site is known as Beit Jamal – the monastery is sometimes referenced as Beit Gemal or Beit Jimal. The name of the site is said to be from its local name (in years past), Kfar Gamla, purportedly so named for Rabban Gamliel I, or Gamaliel in Greek – president of the Sanhedrin. The Christian tradition believes that Gamaliel was buried here, as were St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr and Nicodemus. In 415 their remains were disclosed in a dream and discovered by the priest Lucian, and removed at the orders of John, Bishop of Jerusalem, for depositing in the Church of Hagia Sion on Mt. Zion, at the site of today's Abbey of the Dormition.[5] Thanks to the excavations carried out by Andrzej Strus on site, it is now largely accepted that in Byzantine times this was considered to be the burial site of St Stephen, Gamaliel, Nicodemus and Gamaliel's son Abibos.[6]

In 2003, near a circular structure uncovered by Strus, was found a stone architrave or lintel with a tabula ansata. The writing on it was eventually deciphered by Emile Puech, expert in ancient writing from the Ecole Biblique.[7] The writing ran: "DIAKONIKON STEPHANOU PROTOMARTYROS", "the diakonikon of Stephen the Protomartyr". A diakonikon of a Byzantine church was one of the two spaces or chapels flanking the sanctuary, which often housed holy relics. This is therefore solid evidence for identifying Bet Gemal with the ancient Kfar Gamla, the traditional burial site of St Stephen.[8]

In 2017 extensive remains of a 6th century Byzantine monastery were excavated; finds included a large mosaic featuring birds, foliage and pomegranates.[9]

Ottoman era

Beit Jimal, like the rest of Palestine, was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517, and in the tax registers of 1596, it was a village in the nahiya of Gaza, Sanjak of Gaza, with a population of 37 households, all Muslims. They paid a fixed tax-rate of 33.3% on agricultural products, including wheat, barley, olive trees, goats and beehives, in addition to occasional revenues; a total of 3,500 akçe.[10]

In 1838, Beit el-Jemal was noted as a Muslim village in the Er-Ramleh area.[11] Victor Guérin visited in 1863, and reported that the inhabitants suffered from fevers.[12] An Ottoman village list of about 1870 showed that Bayt Jimal had a population of 21, with a total of 8 houses, though the population count included men, only.[13][14] Land was purchased in 1869 by Fr. Antonio Belloni, who set up the Beit Gemal School of Agriculture for the benefit of underprivileged youth, especially orphans in 1873.[2] By 1881, a Latin Convent was being built there.[3] The Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine in 1883 described Beit Jimal as a small village.[3]

Fr. Belloni, who is said to have come under the influence of the ideas of John Bosco, joined the Salesians, who then took over the property in 1892.[2][15]

British Mandate era

After the war's end, the Ottoman Empire was partitioned and a Palestine mandate was accorded to Britain by the League of Nations. In a census conducted in 1922 by the British Mandate authorities, Bait Jamal had a population of 59; 56 Christians and 3 Muslims,[16] where the Christians were 29 Roman Catholics, 24 Greek Catholics (Melkites) and 2 Maronites.[17]

By the 1931 census this had increased to 168; 78 Christians and 90 Muslims, in a total of 22 houses.[18]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Beit Jimal consisted of 240; 120 Muslims and 120 Christians[19] and the land area was 4,878 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[20] Of this, 715 dunams were designated for plantations and irrigable land, 2,899 for cereals,[21] while 1,264 dunams were classified as non-cultivable land.[22]

During the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, the village was occupied by Egyptian troops, before being evicted by the Har'el Brigade in Operation Ha-Har.[23]

Post-1948

There are two separate monasteries, one for men and a second for women, as well as a small and well-appointed church, called St. Stephen, built in 1930 on the ruins of a 5th-century Byzantine church discovered on the site discovered in 1916, during works to enlarge the monastery garden. The mosaics on the external walls are those excavated from the Byzantine church. Tradition holds that St. Stephen was buried by Gamaliel in his own private tomb in Caphargamala.[2] Fine mosaics from the period were also brought to light.[2] The monastery produces and markets its own honey, olive oil and wine, the last of which is processed at the Cremisan monastery winery just south of Jerusalem. The monastery has a small shop that offers its locally made olive oil and red wines.[2]

An alternative suggests that the cave site may have contained a mikveh belonging to a wealthy Jewish family. The name Beit Jamal appears to preserve the toponym Caphar Gamala (Gamala Village), which in turn suggests a link to rabbi Gamaliel.[2]

A statue erected in 2000 commemorating St Stephen's martyrdom is the work of Israeli artist Yigal Tumarkin.[2]

There is a small concert hall, where concerts are played on some weekends. The nuns do not belong to Salesian Sisters, but rather to the Sisters of Bethlehem, part of the Sisters of the Assumption of the Virgin and the Sisters of Saint Bruno. These nuns have taken a vow of silence.

In 2013, the monastery suffered from a price tag attack, when the hallway of the monastery was firebombed and the slogans "price tag," "death to the Gentiles," and "revenge" were sprayed on its walls.[24][25]

Meteorological station

A meteorological station was established in Beit Jimal in 1919 which is still in operation today.[26]

References

- ↑ Beit el Jemâl, meaning "The house of the camel", according to Palmer, 1881, p. 286

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Aviva and Shmuel Bar-Am, 'Find a spiritual oasis with the monks of Beit Jamal,' The Times of Israel 14 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Conder and Kitchener, 1883, p. 24

- ↑ Dauphin, 1998, pp. 911-2

- ↑ Antonio Scudu, Santo Stefano: primo martire cristiano: morire perdonando (booklet published by Salesiani Don Bosco, Bet Gemal, 2007) 6. (Earlier published in the magazine Maria Ausiliatrice (Turin), December 2006).

- ↑ Scudu 8-9. A. Strus, "Beit-Gemal puo' essere il luogo di sepoltura di Santo Stefano?" Salesianum 54 (1992) 1-26. A. Strus, Bet Gemal: Pathway to the tradition of Saints Stephen and Gamaliel, (Rome, 2000). A. Strus, Khirbet Fattir - Bet Gemal. Two Ancient Jewish and Christian Sites in Israel (Rome: LAS, 2003. A. Strus, "Bet Gemal and the Byzantine Tradition regarding St Stephen," Ecce ascendimus Jerosolymam (Lc 18, 31), ed. F. Mosetto (Rome: LAS, 2003) 399-418. Edgar Krentz, Review of Khirbet Fattir—Bet Gemal: Two Ancient Jewish and Christian Sites in Israel by Andrzej Strus, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 66/3 (July 2007) 234.

- ↑ Emile Puech, "Un mausolée de saint Etienne à Khirbet Jiljil - Beit Gimal (Pl. I)", Revue Biblique 113/1 (January 2006) 100-126.

- ↑ Scudu 9.

- ↑ https://www.qudsn.co/article/135074

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 145

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 119

- ↑ Guérin, 1869, pp. 25-26

- ↑ Socin, 1879, p. 145

- ↑ Hartmann, 1883, p. 140

- ↑ Don Bosco in Terra Santa / en Terre Sainte / in the Holy Land 1891-1991. Centenario dell'arrivo dei Salesiani e delle Figlie di Maria Ausiliatrice in Terra Santa (Jerusalem, 1991), 106.

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Ramleh, p. 21

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XIV, p. 46

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 18

- ↑ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 24

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 56

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 101

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 152

- ↑ Har’el: Palmach brigade in Jerusalem, Zvi Dror (ed. Nathan Shoḥam), Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishers: Benei Barak 2005, p. 270 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Nir Hasson/Associated Press, 'Monastery near Jerusalem defaced in suspected 'price tag' attack,' at Haaretz 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Beit Jimal Monastery Firebombed in Suspected Hate Crime, 8/21/2013

- ↑ The First Meteorological Station - Beit Jamal Archived July 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6. (pp. 447, 462 466 493)

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links

- Welcome To Bayt Jimal

- Images from Beit Jamal

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons