Battle of Sunda Strait

| Battle of Sunda Strait | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II, Pacific War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

American: 1 heavy cruiser Australian: 1 light cruiser Dutch: 1 destroyer |

1 light carrier 1 seaplane carrier 5 cruisers 12 destroyers 1 minelayer 58 troopships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 heavy cruiser sunk 1 light cruiser sunk 1 destroyer sunk 1,071 killed 675 POWs[3] |

1 minelayer sunk, 4 troopships sunk or grounded,[3] 1 cruiser damaged, 3 destroyers damaged 10 killed, 37 wounded[4] | ||||||

| |||||||

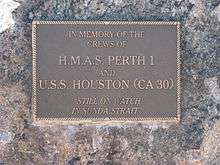

The Battle of Sunda Strait was a naval battle which occurred during World War II in the Sunda Strait between the islands of Java, and Sumatra. On the night of 28 February – 1 March 1942, the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth and the American heavy cruiser USS Houston faced a major Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) task force. After a fierce battle of several hours duration, both Allied ships were sunk. Five Japanese ships were sunk, three of them by friendly fire.

Background

In late February 1942, Japanese amphibious forces were preparing to invade Java, in the Dutch East Indies. On 27 February, the main American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM) naval force, under Admiral Karel Doorman–a Dutch officer–steamed northeast from Surabaya to intercept an imperial Japanese navy invasion fleet. This part of the ABDA force consisted of two heavy cruisers, including USS Houston under the command of Captain Albert H. Rooks, three light cruisers, including HMAS Perth under Captain Hector Waller, and nine destroyers. Only six out of nine of USS Houston's 8-inch (203-millimeter) heavy guns were operational because her aft gun turret had been knocked out in an earlier Japanese air raid. The ABDA force engaged the Japanese force in the Java Sea. The Allied ships were all sunk or dispersed. Houston and Perth both retreated to Tanjung Priok, Java, the main port of Batavia, Dutch East Indies, where they arrived at 13:30 hours on 28 February.

Battle

Later on 28 February, USS Houston and HMAS Perth received orders to sail through Sunda Strait to Tjilatjap, on the south coast of Java. The Dutch destroyer HNLMS Evertsen, which intended to accompany them, was not ready and remained in Tanjung Priok. Houston and Perth left at 19:00, while Evertsen followed an hour later. Waller, who had seniority over Rooks, was in command. The only ships they expected to encounter were Australian corvettes on patrol in and around the strait.

By chance, just after 22:00, the IJA 16th Army's Western Java Invasion Convoy — over 50 transports, and including the Army's commander, Lieutenant General Hitoshi Imamura — was entering Bantam Bay, near the northwest tip of Java. The Japanese troop transports were escorted by the 5th Destroyer Flotilla, led by Rear Admiral Kenzaburo Hara[1] and the 7th Cruiser Division, under Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita.[2] Rear Admiral Hara's light cruiser Natori—with the destroyers Harukaze, Hatakaze, Asakaze, Fubuki, Hatsuyuki, Shirayuki, Shirakumo, and Murakumo—were closest to the convoy. Flanking the bay to the north was Vice Admiral Kurita's cruisers Mogami and Mikuma — and the destroyer Shikinami.

Slightly further north, though not involved in the action, was the aircraft carrier Ryūjō, with Kurita's Suzuya and Kumano — along with the seaplane carrier Chiyoda, and the destroyers Isonami, Shikinami and Uranami.

Some time around 23:15[5], the Allied ships were sighted by the patrolling Fubuki, which followed them surreptitiously. At 23:06, when they were about halfway across the mouth of Bantam Bay, Perth sighted a ship about 5 mi (4.3 nmi; 8.0 km) ahead, near Saint Nicolaas Point. It was thought at first that the ship was an Australian corvette, but when challenged, she made an unintelligible reply, with a lamp which was the wrong color, fired her nine Long Lance (Type 93) torpedoes from about 3,000 yards (2,700 m) and then turned away, making smoke. The ship was soon identified as a Japanese destroyer (probably Harukaze). Waller reported the contact and ordered his forward turrets to open fire.[6]

In a ferocious night action that ended after midnight, the two Allied cruisers were sunk. Two Japanese transports and a minesweeper were sunk by friendly torpedoes. Two other transports — one of which was Ryujo Maru, on which Lt. Gen. Hitoshi Imamura was aboard — were also sunk but later refloated. After Imamura's ship was fatally hit and sank, he had to jump overboard. However a small boat rescued and brought him ashore.[7]

Aftermath

696 men on board the Houston were killed, while 368 others were saved. Perth lost 375 men, with 307 others saved. The captains of both cruisers were also killed. Rooks was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions.

The cruiser Mikuma lost six men and eleven wounded as a result of damage caused by Houston.[8] The destroyer Shirayuki suffered a direct shell hit to her bridge, killing one crewman and injuring eleven others, while Harukaze suffered hits to her bridge, engine room and rudder, killing three crewmen and over 15 injured.[4]

Both Houston and Perth were still engaging the Japanese convoy by the time the Dutch destroyer HNLMS Evertsen arrived. She was trying to catch up with the two cruisers when she saw tracers and intense shellfire ahead. In an attempt to avoid the battle, Evertsen sailed around them and through Sunda Strait. All went well until she encountered the destroyers Murakumo and Shirakumo protecting the southern flank of Bantam Bay, which immediately fired on her. Evertsen altered course and managed to escape, but after re-entering Sunda Strait, she encountered them again. She again managed to escape under a smokescreen, but by then her stern was on fire. Still taking fire from the destroyers, Evertsen attempted to beach on a coastal reef. Firing all her torpedoes, the crew escaped before the fire reached the aft magazine, causing an explosion which blew off most of the stern. The majority of Evertsen's crew was taken prisoner on 9–10 March 1942 and were held by the Japanese for three and a half years.[9]

See also

- Burma Railway

- Houston Volunteers

- Successor namesake USS Houston (CL-81)

- Lost Battalion (Pacific, World War II)

Notes

- 1 2 L, Klemen. "Rear-Admiral Kenzaburo Hara". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- 1 2 L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Rear-Admiral Takeo Kurita". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- 1 2 Order of Battle

- 1 2 Dull. A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy

- ↑ Hornfischer, James D. (2009). Ship of Ghosts: The Story of the USS Houston, FDR's Legendary Lost Cruiser, and the Epic Saga of Her Survivors. Random House Publishing. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ Visser, Jan (1999–2000). "The Sunda Strait Battle". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942. Archived from the original on 3 December 2014.

- ↑ L, Klemen (1999–2000). "The conquest of Java Island, March 1942". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- ↑ HIJMS MIKUMA: Tabular Record of Movement

- ↑ HNLMS Evertsen

References

- D'Albas, Andrieu (1965). Death of a Navy: Japanese Naval Action in World War II. Devin-Adair Pub. ISBN 0-8159-5302-X.

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-097-1.

- Hornfischer, James D. (2006). Ship of Ghosts: The Story of the USS Houston, FDR's Legendary Lost Cruiser, and the Epic Saga of Her Survivors. Bantam. ISBN 0-553-80390-5.

- L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942".

- Lacroix, Eric; Linton Wells (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-311-3.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (2001) [1958]. The Rising Sun in the Pacific 1931 – April 1942, vol. 3 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Castle Books. ISBN 0-7858-1304-7.

- Schultz, Duane (1985). The Last Battle Station: The Story of the USS Houston. St Martins Press. ISBN 0-312-46973-X.

- Skeels, Fred (2008). Java Rabble: A story of a ship, slavery and survival. Victoria Park: Hesperian Press. ISBN 978-0-85905-419-5.

- van Oosten, F. C. (1976). The Battle of the Java Sea (Sea battles in close-up; 15). Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-911-1.

- Spector, Ronald (1985). "The Short, Unhappy Life of ABDACOM". Eagle Against the Sun : The American War With Japan. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-394-74101-3.

- Whiting, Brendan (1995). Ship of Courage: The Epic Story of HMAS Perth and Her Crew. Australia: Allen & Unwin Pty., Limited. ISBN 1-86373-653-0.

- Winslow, Walter G. (1984). The Ghost that Died at Sunda Strait. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-218-4. - Firsthand account of the battle by a survivor from USS Houston

- Winslow, Walter G. (1994). The Fleet the Gods Forgot: The U.S. Asiatic Fleet in World War II. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-928-X.

Further reading

- Gill, G. Hermon (1957). "Chapter 16 – Defeat in Abda". Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. Volume I. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 848228.

- Lewis, Tom. 2011. The Submarine Six: the stories of the naval heroes who had the Collins-class submarines of the RAN named after them. Avonmore Books. Adelaide.

External links

- Naval History (no date), "1942 03 01 0100 Surface Action Battle Of Sunda Strait"

- "US Navy report of the battle from 1943". Archived from the original on 15 May 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-17.

- United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific) – Naval Analysis Division (1946). "Chapter 3: The Japanese Invasion of the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, and Southeast Asia". The Campaigns of the Pacific War. United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved 2006-11-20.

- Muir, Dan Order of Battle – The Battle of the Sunda Strait 1942