Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on Sunday, January 8, 1815,[1] between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham, and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson.[2] It took place approximately 5 miles (8.0 kilometres) south of the city of New Orleans,[3] close to the present-day town of Chalmette, Louisiana, and was an American victory.[2] The battle effectively marked the end of the War of 1812.[4]

Background

On October 24, 1814, in Pakenham's Secret Orders the Secretary of War and the Colonies, Henry Bathurst wrote:

War Department

24th October 1814

M Genl The Hon

Sir E. Pakenham

Secret

Sir:

It has occurred to me that one case may arise affecting your situation upon the Coasts of America for which the Instructions addressed to the late Major General Ross have not provided.

You may possibly hear whilst engaged in active operations that the Preliminaries of Peace between His Majesty and the United States have been signed in Europe and that they have been sent to America in order to receive the Ratification of The President.

As the Treaty would not be binding until it shall have received such Ratification in which we may be disappointed by the refusal of the Government of the United States, it is advisable that Hostilities should not be suspended until you shall have official information that The President has actually ratified the Treaty and a Person will be duly authorized to apprise you of this event.

As during this interval, judging from the experience we have had, the termination of the war must be considered as doubtful, you will regulate your proceedings accordingly, neither omitting an opportunity of obtaining signal success, nor exposing the troops to hazard or serious loss for an inconsiderable advantage. And you will take special care not so to act under the expectation of hearing that the Treaty of Peace has been ratified, as to endanger the safety of His Majesty’s Forces, should that expectation be unhappily disappointed.

I have etc.

Bathurst[5]

Prelude

Lake Borgne

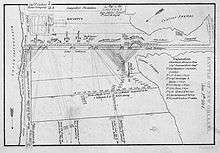

By December 14, 1814, sixty British ships with 14,450 soldiers and sailors aboard, under the command of Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, had anchored in the Gulf of Mexico to the east of Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Borgne.[6][7] Preventing access to the lakes was an American flotilla, commanded by Lieutenant Thomas ap Catesby Jones, consisting of five gunboats. On December 14, around 1,200 British sailors and Royal Marines under Captain Nicholas Lockyer[8] set out to attack Jones' force. Lockyer's men sailed in 42 longboats, each armed with a small carronade. Lockyer captured Jones' vessels in a brief engagement known as the Battle of Lake Borgne. 17 British sailors were killed and 77 wounded,[9] while 6 Americans were killed, 35 wounded, and 86 captured.[9] The wounded included both Jones and Lockyer. Now free to navigate Lake Borgne, thousands of British soldiers, under the command of General John Keane, were rowed to Pea Island (possibly now Pearl Island) where they established a garrison, about 30 miles (48 km) east of New Orleans.[10]

Villeré Plantation

On the morning of December 23, Keane and a vanguard of 1,800 British soldiers reached the east bank of the Mississippi River, 9 miles (14 km) south of New Orleans.[12] Keane could have attacked the city by advancing for a few hours up the river road, which was undefended all the way to New Orleans, but he made the fateful decision to encamp at Lacoste's Plantation[13] and wait for the arrival of reinforcements.[14]

Meanwhile, General Jackson learned of the advances and position of the British encampment from Colonel Pierre Denis (born Denys) de La Ronde (upon whose plantation, commonly misnamed Versailles, Louisiana, the night battle was later largely fought)[15]) and his son-in-law, Gabriel Villeré, son of Colonel Jacques Villeré. The young major had escaped through a window after capture, when the advancing British invaded his family home.[16][17]

At the close of Major Villere's narrative the General drew up his figure, bowed with disease and weakness, to its full height, and with an eye of fire and an emphatic blow upon the table with his clenched fist, exclaimed: 'By the Eternal, they shall not sleep on our soil!

— Stanley Clisby Arthur, The Story of the Battle of New Orleans[15]

That evening, Jackson, attacking from the north, led 2,131[18] men in a brief three-pronged assault on the unsuspecting British troops, who were resting in their camp. Jackson then pulled his forces back to the Rodriguez Canal, about 4 miles (6.4 km) south of the city. The Americans suffered 24 killed, 115 wounded, and 74 missing,[19] while the British reported their losses as 46 killed, 167 wounded, and 64 missing.[20]

Historian Robert Quimby says, "The British certainly did win a tactical victory, which enabled them to maintain their position."[21] However, Quimby goes on to say, "It is not too much to say that it was the battle of December 23 that saved New Orleans. The British were disabused of their expectation of an easy conquest. The unexpected and severe attack made Keane even more cautious... he made no effort to advance on the twenty-fourth or twenty-fifth."[22] As a consequence, the Americans were given time to begin the transformation of the canal into a heavily fortified earthwork.[23] On Christmas Day, General Edward Pakenham arrived on the battlefield and ordered a reconnaissance-in-force on December 28 against the American earthworks protecting the advance to New Orleans. That evening, General Pakenham, angry with the position in which the army had been placed, met with General Keane and Admiral Cochrane for an update on the situation. General Pakenham wanted to use Chef Menteur Road as the invasion route, but he was overruled by Admiral Cochrane, who insisted that his boats were providing everything that could be needed.[24] Admiral Cochrane believed the veteran British soldiers would easily destroy Jackson's ramshackle army, and he allegedly said that if the army did not do it, his sailors would. Whatever Pakenham's thoughts on the matter, the meeting settled the method and place of the attack.[25]

When the British reconnaissance-in-force withdrew, the Americans immediately began constructing earthworks to protect the artillery batteries. These defenses were christened Line Jackson. The Americans installed eight batteries, which included one 32-pound gun, three 24-pounders, one 18-pounder, three 12-pounders, three 6-pounders, and a 6-inch (150 mm) howitzer. Jackson also sent a detachment to the west bank of the Mississippi to man two 24-pounders and two 12-pounders on the grounded warship USS Louisiana. Even so, Jackson's force was greatly outnumbered by the attacking forces. Jackson's total of 4,732 men was made up of 968 United States Army regulars,[26] 58 United States Marines (holding the center of the defensive line), 106 seamen of the United States Naval Battalion, 1,060 Louisiana militia and volunteers (including 462 free people of color), 1,352 Tennessee militia, 986 Kentucky militia, 150 Mississippi militia, and 52 Choctaw warriors, along with a force from the pirate Jean Lafitte's Baratarians. Jackson also had the support of the warships in the Mississippi River, including USS Louisiana, USS Carolina and Enterprise, a steamboat.

Then Major Thomas Hinds' Squadron of Light Dragoons, a militia unit from the Mississippi Territory, learned of the advancing position of the British on December 30, helping to secure victory, Hinds having arrived to the battle December 22 and distinguished himself and the cavalry under his command.[27][28]

The main British army arrived on New Year's Day, 1815, and began an artillery bombardment of the American earthworks. This began an exchange of artillery fire that continued for three hours. Several of the American guns were destroyed or silenced, including the 32-pounder, a 24-pounder, and a 12-pounder, while some damage was done to the earthworks. The British artillery finally exhausted its ammunition, which caused Pakenham to cancel the attack. Pakenham did not know that his attack had come close to success, since the American defenders on the left of Line Jackson near the swamp had broken under the fire and abandoned their position. Pakenham decided to wait for his entire force of over 8,000 men to assemble before continuing his attack. The British regulars included the 4th, 7th, 21st, 43rd, 44th, 85th, 93rd, a 500-man "demi-battalion" of the 95th Rifles, 14th Light Dragoons, and the 1st and 5th West India Regiments of several hundred free black soldiers, recruited from the British West Indies colonies. Other troops included Native Americans of the Hitchiti tribe, led by Kinache.

Battle

On January 8, 1815 at 05:00, the British marched against General Andrew Jackson's lines of defense. The British infantry and one rifle unit advanced in two columns under the cover of artillery.[29] The Americans had constructed three lines of defense, the forward one four miles in front of the city; it was strongly entrenched at the Rodriguez Canal, which stretched from a swamp to the river, with a timber, loopholed breastwork and earthworks for artillery.[30]:361 [31]

The British battle plan was for an attack against the 20-gun west bank battery, which would then both reduce the American artillery danger and enable those same guns to be turned on the American line to assist a frontal attack against the defended line.[30]:362 In the early morning of January 8, Pakenham gave his final orders for the two-pronged assault against Jackson's position. Colonel William Thornton (of the 85th Regiment) was to cross the Mississippi during the night with his 780-strong force, move rapidly upriver and storm the battery commanded by Commodore Daniel Patterson on the flank of the main American entrenchments, and then open an enfilade fire on Jackson's line with the captured artillery, directly across from the earthworks manned by the vast majority of American troops[32] would be launched in two columns, along the river led by Keane and along the swamp line led by Major General Samuel Gibbs. The brigade commanded by Major General John Lambert was held in reserve.

A canal was dug by the British to enable 42 small boats to get to the river.[30]:362 Preparations for the attack had foundered early on the 8th, as the canal being dug by Cochrane's sailors collapsed and the dam made to divert the flow of the river into the canal failed, leaving the sailors to drag the boats of Col. Thornton's west bank assault force through deep mud. This left the force starting off just before daybreak, 12 hours late.[33] The frontal attack was not postponed, however, as it was hoped that the force on the west bank would at least create a diversion, even if they had not succeeded in the assault.[30]:362

The main attack began in darkness and a heavy fog, but as the British neared the main enemy line the fog lifted, exposing them to withering artillery fire. Lt-Col. Thomas Mullins, the British commander of the 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot, had forgotten the ladders and fascines needed to cross the eight-foot-deep and fifteen-foot-wide canal[30]:361 and scale the earthworks, and in the dark and fog confusion descended as the British tried to close the gap. Most of the senior officers were killed or wounded, including Major General Samuel Gibbs, who was killed leading the main attack column on the right, consisting of the 4th, 21st, 44th, and 5th West India Regiments, and Colonel Rennie, who led a detachment of three light companies of the 7th, 43rd, and 93rd on the left by the river.

Possibly because of Thornton's delay in crossing the river and the withering artillery fire that might hit them from across the river, the 93rd Highlanders were ordered to leave Keane's assault column advancing along the river and move across the open field to join the main force on the right of the field. Keane fell wounded as he crossed the field with the 93rd. Rennie's men managed to attack and overrun an American advance redoubt next to the river, but without reinforcements they could neither hold the position nor successfully storm the main American line behind it. Within a few minutes, the American 7th Infantry arrived, moved forward, and fired upon the British in the captured redoubt: within half an hour, Rennie and nearly all of his men were dead. In the main attack on the right, the British infantrymen either flung themselves to the ground, huddled in the canal, or were mowed down by a combination of musket fire and grapeshot from the Americans. A handful made it to the top of the parapet on the right but were either killed or captured. The 95th Rifles had advanced in open skirmish order ahead of the main assault force and were concealed in the ditch below the parapet, unable to advance further without support.

The two large main assaults on the American position were repulsed. Pakenham and his second-in-command, Major General Samuel Gibbs, were fatally wounded while on horseback, by grapeshot fired from the earthworks. Major Wilkinson of the 21st Regiment reformed his lines and made a third assault. They were able to reach the entrenchments and attempted to scale them. Wilkinson made it to the top, before being shot. The Americans were amazed at his bravery and carried him behind the rampart. With most of their senior officers dead or wounded, the British soldiers, including the 93rd Highlanders, having no orders to advance further or retreat, stood out in the open and were shot apart with grapeshot from Line Jackson. General Lambert was in the reserve and took command. He gave the order for his reserve to advance and ordered the withdrawal of the army. The reserve was used to cover the retreat of what was left of the British army in the field.

The Chalmette battlefield was the plantation home of Colonel Denis de La Ronde's half-brother, Ignace Martin de Lino (1755–1815). It was burned by invading forces, reputedly causing de Lino's death from a broken heart shortly after returning to his "treasured home" three weeks after the battle.[34]

The only British success of the battle was the delayed attack on the west bank of the Mississippi River, where Thornton's brigade, comprising the 85th Regiment and detachments from the Royal Navy and Royal Marines,[35][36][37] attacked and overwhelmed the American line.[38] The Navy detachment and the Marine detachment were led by Captain Rowland Money and Brevet Major Thomas Adair, respectively. Money was captain of HMS Trave, and Adair was the commanding officer of HMS Vengeur's detachment of Marines.[39] The sides of the canal by which the boats were to be brought through to the Mississippi caved in and choked the passage, so that only enough got through to take over a half of Thornton’s force. With these, seven hundred in number, he crossed, but as he did not allow for the current; it carried him down about two miles below the intended landing place. Thornton’s brigade won their battle, but Colonel Thornton was dangerously wounded. This success, though a notable one and a disgrace to the American arms, had no effect on the battle.[40] Army casualties among the 85th Foot were 2 dead, 1 captured, and 41 wounded.[38] Royal Navy casualties were 2 dead, Captain Rowland Money and 18 seamen wounded. Royal Marine casualties were 2 dead, with 3 officers, 1 sergeant and 12 other ranks wounded. Though both Jackson and Commodore Patterson reported that the retreating forces had spiked their cannon, leaving no guns to turn on the Americans' main defense line, Major Mitchell's diary makes it clear this was not so, as he states he had "Commenced cleaning enemy's guns to form a battery to enfilade their lines on the left bank".[41] General Lambert ordered his Chief of Artillery, Colonel Alexander Dickson, to assess the position. Dickson reported back that no fewer than 2,000 men would be needed to hold the position. General Lambert issued orders to withdraw after the defeat of their main army on the east bank and retreated, taking a few American prisoners and cannon with them.[38][42] It was later learned that the Americans were so dismayed by the loss of this battery, which would be capable of inflicting such damage on their lines when the attack was renewed, that they were preparing to abandon the town when they received the news that the British themselves were withdrawing.[30]:363

The Battle of New Orleans was remarkable for both its brevity and lopsided lethality, though some numbers are in dispute and contradict the official statistics. Charles Welsh[43] and Zachary Smith [44] echo the report of Adjutant-general Robert Butler, in his official report to General Jackson, which claimed that in the space of twenty-five minutes, the British lost 285 killed, 1265 wounded, and 484 prisoners, a total loss of 2084 men; American losses were only 13 killed, 30 wounded, and 19 missing or captured.[45] After the battle was over, around 484 British soldiers who had pretended to be dead rose up and surrendered to the Americans. One bugle boy climbed a tree within 200 yards of the American line and played throughout the battle, with projectiles passing close to him. He was captured after the battle and considered a hero by the Americans.

Almost universal blame was assigned to Colonel Mullins, of the 44th Regiment, which was detailed under orders to prepare and have ready, and to carry to the front on the morning of the eighth, fascines and ladders with which to cross the ditch and scale the parapet, as the soldiers fought their way to the breastwork of the Americans. It was freely charged that the Colonel deserted his trust and at the moment of need was half a mile to the rear. It was then that Pakenham, learning of Mullins' conduct, placed himself at the head of the 44th and endeavored to lead them to the front with the implements needed to storm the works, when at around 500 yards away from the enemy front line, he fell wounded after being hit with grapeshot. On being assisted onto a horse, Pakenham was hit again and fell, this time mortally wounded.[30]:363[46]

Aftermath

Fort St. Philip

The British planned to sail up the Mississippi River; however Fort St. Philip stood in the way. On January 9, British naval forces attacked Fort St. Philip, which protected New Orleans from an amphibious assault from the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi River. The American forces, in addition to gunners working from privateer ships, were able to fend off the attacks. They withstood ten days of bombardment by cannon before the British ships withdrew on January 18, 1815.

Withdrawal of the British

Three days after the battle, General Lambert held a council of war where, despite just receiving the news that the battery on the west bank of the river had been captured, it was concluded that despite his request for reinforcements as well as a siege train, capturing New Orleans and continuing the Louisiana campaign would be too costly and thus agreed with his officers to withdraw.[30]:363 By January 19 the British camp at Villere's Plantation had been abandoned.[47][48]

On February 4, 1815, the fleet, with all of the British troops aboard, set sail toward Mobile Bay, Alabama.[49][50][51] The British army then attacked and captured Fort Bowyer at the mouth of Mobile Bay on February 12. The following day, the British army was making preparations to attack Mobile when news arrived of the peace treaty. General Jackson had made tentative plans to attack the British at Mobile and continue the war into Spanish Florida on the grounds the British were using it as a base. He carried out those plans for Florida much later. The treaty had been ratified by the British Parliament but would not be ratified by Congress and the President until mid-February. It did, however, resolve that hostilities should cease, and the British abandoned Fort Bowyer and sailed home to their base in the West Indies.[52] Although the Battle of New Orleans had no influence on the terms of the Treaty of Ghent, the defeat at New Orleans did compel Britain to abide by the treaty.[53]

It would have been problematic, in any case, for the British to continue the war in North America because of Napoleon's escape from Elba on February 26, 1815, which ensured their forces were needed in Europe.[54] Also, since the Treaty of Ghent did not specifically mention the vast territory America had acquired with the Louisiana Purchase, it only required both sides to give back those lands that had been taken from the other during the war.[55]

From December 25, 1814, to January 26, 1815, British casualties, apart from the assault on January 8, were 49 killed, 87 wounded and 4 missing.[56] Thus, British casualties for the entire campaign totaled 2,459 with 386 killed, 1,521 wounded, and 552 missing. American casualties for the entire campaign totaled 333 with 55 killed, 185 wounded, and 93 missing.[57] Six active Regular Army battalions of the United States Army (1st and 2d battalions of the 1st Infantry Regiment, 2d and 3d battalions of the 7th Infantry Regiment, 1st Battalion of the 5th Field Artillery Regiment, and 1st Battalion of the 6th Field Artillery Regiment) and one regiment of the Mississippi Army National Guard (155th Infantry Regiment) are credited by the United States Army Center of Military History with campaign participation at the Battle of New Orleans.

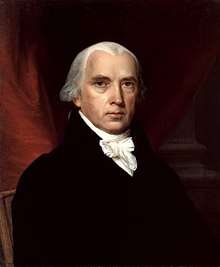

Although the engagement was small in scale compared to other contemporary battles of 1815, such as the Battle of Waterloo, it was important for the meaning applied to it by Americans in general and Andrew Jackson in particular.[58] They believed that a vastly powerful British fleet and army had sailed for New Orleans (Jackson himself thought 25,000 troops were coming), and most expected the worst. The news of victory, one man recalled, "came upon the country like a clap of thunder in the clear azure vault of the firmament, and traveled with electromagnetic velocity, throughout the confines of the land."[59] The battle boosted the reputation of Jackson and helped to propel him ultimately to the White House. The battle was immediately politicized by the Democratic-Republican Party. Across the nation, it used the great victory to ridicule the Federalists as cowards, defeatists, and secessionists. Pamphlets, songs, newspaper editorials, speeches and entire plays on the battle drove home the point, and glorified Jackson's heroic image.[60]

Legacy

Miracle at New Orleans

With the Americans outnumbered it seemed as though the city of New Orleans was in danger of being captured. Consequently, the Ursuline nuns along with many faithful people of New Orleans gathered in the Ursuline Convent's chapel before the statue of Our Lady of Prompt Succor. They spent the night before the battle praying and crying before the holy statue, begging for the Virgin Mary's intercession.

On the morning of January 8, the Very Rev. William Dubourg, Vicar General, offered Mass at the altar on which the statue of Our Lady of Prompt Succor had been placed. The Prioress of the Ursuline convent, Mother Ste. Marie Olivier de Vezin, made a vow to have a Mass of Thanksgiving sung annually should the American forces win. At the very moment of communion, a courier ran into the chapel to inform all those present that the British had been defeated.

General Jackson went to the convent himself to thank the nuns for their prayers: "By the blessing of heaven, directing the valor of the troops under my command, one of the most brilliant victories in the annals of war was obtained."[61] The vow made by Mother Ste. Marie has been faithfully kept throughout the years.[62]

Distinguished service as mentioned in dispatches

In his general orders of January 21, General Jackson, in thanking the troops, paid special tributes to the Louisiana organizations, and made particular mention of Capts. Dominique and Belluche, and the Lafitte brothers, all of the Barataria privateers; of General Garrique de Flanjac, a State Senator, and brigadier of militia, who served as a volunteer; of Majors Plauche, St. Geme. Lacoste, D'Aquin, Captain Savary, Colonel De la Ronde, General Humbert, Don Juan de Araya, the Mexican Field-Marshal; Major-General Villere and General Morgan, the Engineers Latour and Blanchard; the Attakapas dragoons, Captain Dubuclay; the cavalry from the Felicianas and the Mississippi territory. General Labattut had command of the town, of which Nicolas Girod was then the mayor.

— William Head Coleman, Historical sketch book and guide to New Orleans and environs[63]

Among those who most distinguished themselves during this brief but memorable campaign, were, next to the Commander-in-chief, Generals Villere, Carroll, Coffee, Ganigues, Flanjac, Colonel Delaronde, Commodore Patterson, Majors Lacoste, Planche, Hinds, Captain Saint Gerne, Lieutenants Jones, Parker, Marent, and Dominique; Colonel Savary, a man of colour nor must we omit to mention Lafitte, pirate though he was.

— E. Bunner, History of Louisiana[17]

Over the course of several days, the logistically and numerically superior British force was repelled, in no small part to a small contingent of Marines led by Maj. Daniel Carmick and Lt. Francis de Bellevue of the New Orleans Navy Yard [François-Godefroy Barbin de Bellevue (1789-1845)].

— 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit A Certain Force in an Uncertain World[64]

At the Battle of New Orleans, [Governor Claiborne's aide-de-camp Bernard de] Marigny distinguished himself by his courage and activity. It is noteworthy that the glorious victory was reaped on the fields of the plantation of his Uncle [Martin] de Lino de Chalmette. In 1824 he supported General Jackson for President not only with his usual fiery eloquence, but also, perhaps more effectively, with force of arms. He was an ardent duelist and an expert with sword and pistol, and he has been credited with fifteen or more encounters. [Footnote:] Bernard Marigny's Réflexions sur la campagne du Général André Jackson en Louisiane en 1814 et 1815, New Orleans; 1848, is the best account we have of the preparations made to meet the enemy before the battle; and of the ensuing episode. — Library of Louisiana Historical Society."

— Grace King, Old Families of New Orleans[65]

The anniversary of the battle was celebrated as a United States holiday for many years, called "The Eighth", following Jackson's election as President and ended after 1861.[66] "The Eighth" is still a holiday in Louisiana.

Monuments and memorials

In honor of Jackson, the newly organized Louisiana Historical Association dedicated its new Memorial Hall facility on January 8, 1891, the 76th anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans.[67]

Postage

The sequicentennial of the Battle of New Orleans and 150 years of British – United States peace was commemorated with a five-cent stamp in 1965. The bicentennial was celebrated in 2015 with a Forever stamp depicting United States troops firing on British soldiers from along Jackson's Line.

Sesquicentennial issue of 1965 |

Bicentennial issue of 2015 |

Battlefield preservation

A United States national historical park was established in 1907 to preserve the Chalmette Battlefield; today the park features a monument and is part of the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve.

In popular culture

- The 8th of January became a traditional American fiddle tune, honoring the date of the battle. More than a century later, the melody was used by Jimmie Driftwood to write the song "The Battle of New Orleans", which was a hit for Johnny Horton and Lonnie Donegan. That song was converted into punk rock tune for the play Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson.

- The Battle and General Andrew Jackson are mentioned in George Washington Dixon's 1834 version of "Zip Coon", a popular minstrel show song.

- The Buccaneer was a 1938 American adventure film produced and directed by Cecil B. De Mille based on Jean Lafitte and the Battle of New Orleans. The movie was remade in 1958.

- Country singer Johnny Horton had a Number 1 hit in 1959 with "The Battle of New Orleans" (written by Jimmy Driftwood), which won the 1960 Grammy Award for Best Country & Western Recording and was awarded the Grammy Hall of Fame Award. It was ranked No. 333 of the Recording Industry Association of America's "Songs of the (20th) Century." The melody is from a 19th-century fiddle tune, "The Eighth of January," which presumably was inspired by the American victory. Also in 1959, Lonnie Donegan, the "King of Skiffle", also had a U.K. Number 2 hit with his cover of "The Battle of New Orleans."

- Folk singer Phil Ochs mentions the Battle Of New Orleans in the opening stanza of his 1964 anti-war protest song, "I Ain't Marching Any More."

- The Battle features prominently in Episode #5 "The Last Patrol," of the 1966 American television series The Time Tunnel.

- The Battle was mentioned in Johnny Cash's 1974 song "Ragged Old Flag."

- The Battle is also depicted in Eric Flint's 2005 alternate history novel 1812: The Rivers of War, wherein the battle was decided when a battalion of black United States soldiers ("The Iron Battalion") repelled the British assault.

- The final song of the play Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, "The Hunters of Kentucky," is a punk rock rendition of the 19th century song of the same name.

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 Stoltz, Joseph F. III (2014). The Gulf Theater, 1813-1815 (PDF). The U.S. Army Campaigns of the War of 1812. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 30–40. CMH Pub 74–7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Battle of New Orleans Facts & Summary". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ↑ "The Battle of New Orleans". National Geographic Society. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ↑ "The Treaty of Ghent". National Park Service. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ↑ "Instructions to Major-General Sir Edward Pakenham for the New Orleans Campaign". The War of 1812 Magazine, Issue 16: September 2011. Missing or empty

|url=(help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Smith, Zachary F., pp.1-2.

Smith described in detail the British expedition as "a fleet of sixty great ships", "Nearly one half of these vessels were formidable warships, the best of the English navy," that had transported "not fewer than eighteen thousand men [including 14,450 soldiers and sailors], veterans in the service of their country in the lines of their respective callings, to complete the equipment of this powerful armada." - ↑ Refer to the map of Louisiana.

- ↑ Quimby, p. 824.

- 1 2 Quimby, p. 826.

- ↑ Russell Guerin. "A Creole In Mississippi".

- ↑ Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 1032.

- ↑ Remini (1999), pp. 62–64.

- ↑ Quimby, p. 836.

- ↑ Thomas, p. 61.

- 1 2 Arthur, Stanley Clisby; Louisiana Historical Society (September 25, 2017). "The story of the battle of New Orleans". New Orleans, La., Louisiana historical society – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ "NPS Historical Handbook: Jean Lafitte". www.nps.gov.

- 1 2 Bunner, E. (September 25, 2017). "History of Louisiana, from its first discovery and settlement to the present time". New York, Harper & brothers – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Quimby, p. 843.

- ↑ James, pp. 535–536.

- ↑ Thomas, pp. 61–64.

- ↑ Quimby, p. 852.

- ↑ Quimby, pp. 852–853.

- ↑ Groom, pp. 145–147.

- ↑ Patterson, Benton Rain, pp. 214–215.

- ↑ Patterson, Benton Rain, pp. 215–216.

- ↑ "French Creoles - Battalion of Creoles 1".

- ↑ Remini, Robert V. (1999), The Battle of New Orleans. p. 74.

- ↑ Hinds' Dragoons became the 155th Infantry Regiment of the Mississippi Army National Guard, one of only 19 Army National Guard units with campaign credit for the War of 1812.

- ↑ History, U.S. Army Center of Military. "The Battle of New Orleans, 1815 | Center of Military History". history.army.mil. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- ↑ History.com staff. "January 08, 1815: The Battle of New Orleans". History.com. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ↑ United States forces (3,500 to 4,500 strong) were composed of United States Army troops; state militiamen from Tennessee, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Louisiana; United States Marines; United States Navy sailors; Barataria Bay pirates; Choctaw Indians; "freemen of color" and freed black slaves (a large amount of the work building the parapet however was done by local black slaves). Major-General Jacques Villeré, who would become Louisiana's first Creole Governor the following year, commanded the Louisiana Militia, and Major Jean Baptiste Plauché headed the New Orleans uniformed militia companies.

- ↑ Patterson, Benton Rain, p. 236.

- ↑ "New Orleans Bar Association: Chalmette, by Ned Hémard; 2011, p. 3" (PDF).

- ↑ Patterson, Benton Rain, p. 230.

- ↑ "Correspondence from Cochrane, ADM 1/508 folio 757, states 'the whole amounting to about six hundred men'".

- ↑ Gleig, George (1840). "Recollections of the Expedition to the Chesapeake, and against New Orleans, by an Old Sub". United Service Journal (2).

Gleig, on p340, uses the source document a report from Thornton to Pakenham 'we were unable to proceed across the river until eight hours after the time appointed, and even then with only a third part of the force which you had allotted for the service * viz 298 of the 85th, and 200 Seamen and Marines'

- 1 2 3 "No. 16991". The London Gazette. March 9, 1815. pp. 440–446.

- ↑ The Navy List, Corrected to the end of January 1815, pg 72. John Murray. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Theodore (1882). The Naval War of 1812. New York: G.P. Putnam's sons. p. 204.

- ↑ Reilly, Robin, p. 296.

- ↑ Patterson, Benton Rain, p. 253.

- ↑ Welsh, Charles (Oct–Dec 1899). "Rhyme Relating to the Battle of New Orleans". The American Folklore. 12 (47): 291. JSTOR 533063.

- ↑ Smith, Zachary (1904). The Battle of New Orleans including the Previous Engagements between the Americans and the British, the Indians and the Spanish which led to the Final Conflict on the 8th of January, 1815 (19 ed.). Louisville, KY: Filson Club Publications. p. 85.

- ↑ https://history.army.mil/news/2015/150100a_newOrleans.html

- ↑ Smith, Zachary (1904). The Battle of New Orleans including the Previous Engagements between the Americans and the British, the Indians and the Spanish which led to the Final Conflict on the 8th of January, 1815 (19 ed.). Louisville KY: Filson Club Publications. p. 105.

- ↑ Gleig, p. 340:

"These preparations [to withdraw] being continued for some days, on the 17th [of January] no part of our force remained in camp except the infantry. Having delayed therefore only till the abandoned guns were rendered unserviceable, on the evening of the 18th it also began its retreat." - ↑ Latour, p. 184:

"On the morning of the 19th [of January], it was perceived that the enemy [British] had evacuated, not a single man appearing." - ↑ Gleig, George Robert (1827), pp. 184–192.

- ↑ James, p. 391.

- ↑ Smith, Zachary F., p. 132.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 297, quote: 'Rear Admiral Cockburn, at the end of February, was making preparations for a move on Savannah in March when official intelligence that the treaty of peace had been signed by the American President reached him and all proceedings were stopped. The force continued on Cumberland Island until, early in April, it was informed that the treaty had been ratified, on which all withdrew to Bermuda prior to returning to England.'

- ↑ Remini (1999), pp. 5, 195.

- ↑ Lambert, p. 381 "While Napoleon remained in power, few British soldiers could be spared for North America. Wellington was always looking for more manpower."

- ↑ "Avalon Project - British-American Diplomcay : Treaty of Ghent; 1814".

- ↑ James, pp. 542, 543, 568.

- ↑ James, p. 563.

- ↑ "BBC - Radio 4 - America".

- ↑ Ward 1962, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Joseph F. Stoltz, "'It Taught our Enemies a Lesson:' The Battle of New Orleans and the Republican Destruction of the Federalist Party." Tennessee Historical Quarterly 71#2 (2012): 112-127. in JSTOR

- ↑ Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, Volume 23, By American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, p. 128 (1912).

- ↑ Arthur, pp. 239–242.

- ↑ Coleman, William Head (September 25, 1885). "Historical sketch book and guide to New Orleans and environs, with map. Illustrated with many original engravings; and containing exhaustive accounts of the traditions, historical legends, and remarkable localities of the Creole city". New York, W. H. Coleman – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ "26th Marine Expeditionary Unit sails south to New Orleans".

- ↑ King, G. (1921). "Creole Families of New Orleans". New York, THE MACMILLAN COMPANY. p. 33 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ "The War of 1812", Northeast Regional Office, National Park Service, Eastern National, published in 2013, p. 147

- ↑ "Kenneth Trist Urquhart, "Seventy Years of the Louisiana Historical Association", March 21, 1959, Alexandria, Louisiana" (PDF). lahistory.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

Bibliography

- Arthur, Stanley Clisby (1915), The story of the Battle of New Orleans, New Orleans: Louisiana Historical Society, OCLC 493033588

- Borneman, Walter H. (2004), 1812: The War that forged a nation, New York: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-053112-6

- Brooks, Charles B. (1961), The Siege of New Orleans, Seattle: University of Washington Press, OCLC 425116

- Brown, Wilburt S (1969), The Amphibious Campaign for West Florida and Louisiana, 1814–1815, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, ISBN 0-8173-5100-0

- Chapman, Ron (2013). The Battle of New Orleans: "But For A Piece Of Wood". Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4836-9761-1.

- Cooper, John Spencer (1996) [1869], Rough Notes of Seven Campaigns in Portugal, Spain, France and America During the Years 1809–1815, Staplehurst: Spellmount, ISBN 1-873376-65-0

- Drez, Ronald J. (2014). The War of 1812, conflict and deception: the British attempt to seize New Orleans and nullify the Louisiana Purchase. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 362 pages, ISBN 978-0-8071-5931-6.

- Forrest, Charles Ramus (1961), The Battle of New Orleans: a British view; the journal of Major C.R. Forrest; Asst. QM General, 34th. Regiment of Foot, New Orleans: Hauser Press, OCLC 1253280

- Fraser, Edward, & L. G. Carr-Laughton (1930). The Royal Marine Artillery 1804–1923, Volume 1 [1804–1859]. London: The Royal United Services Institution. OCLC 4986867

- Gleig, George Robert (1827), The Campaigns of the British Army at Washington and New Orleans, 1814–1815, London: J. Murray, ISBN 0-665-45385-X

- Groom, Winston. Patriotic Fire: Andrew Jackson and Jean Laffite at the Battle of New Orleans. New York: Vintage Books, 2006. ISBN 1-40004-436-7

- Hickey, Donald R. Glorious Victory: Andrew Jackson and the Battle of New Orleans (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015). xii, 154 pp.

- James, William (1818), A full and correct account of the military occurrences of the late war between Great Britain and the United States of America; with an appendix, and plates. Volume II, London: Printed for the author and distributed by Black et al., ISBN 0-665-35743-5, OCLC 2226903

- Lambert, Andrew (2012), The Challenge: Britain Against America in the Naval War of 1812, London: Faber and Faber, ISBN 0-571-27319-X

- Latour, Arsène Lacarrière (1999) [1816], Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814–15, with an Atlas, Gainesville: University Press of Florida, ISBN 0-8130-1675-4, OCLC 40119875

- Maass, Alfred R (1994), "Brownsville's steamboat Enterprize and Pittsburgh's supply of general Jackson's army", Pittsburgh History, 77: 22–29, ISSN 1069-4706

- Caffrey, Kate (1977), The Twilight's Last Gleaming, New York: Stein and Day, ISBN 0-8128-1920-9

- Owsley, Frank (1981), Struggle for the Gulf borderlands: the Creek War and the battle of New Orleans 1812–1815, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, ISBN 0-8173-1062-2

- Patterson, Benton Rains (2008), The Generals, Andrew Jackson, Sir Edward Pakenham, and the road to New Orleans, New York: New York University Press, ISBN 0-8147-6717-6

- Pickles, Tim (1993), New Orleans 1815, Osprey Campaign Series, 28, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-150-8, OCLC 52914335 .

- Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- Quimby, Robert S. (1997), The U.S. Army in the War of 1812: an operational and command study, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, ISBN 0-87013-441-8

- Reilly, Robin (1974), The British at the gates – the New Orleans campaign in the War of 1812, New York: Putnam, OCLC 839952

- Remini, Robert V. (1977), Andrew Jackson and the course of American empire, 1767–1821, New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 0-06-013574-3

- Remini, Robert V. (1999), The Battle of New Orleans, New York: Penguin Putnam, Inc., ISBN 0-670-88551-7

- Rowland, Eron (1971) [1926], Andrew Jackson's Campaign against the British, or, the Mississippi Territory in the War of 1812, concerning the Military Operations of the Americans, Creek Indians, British, and Spanish, 1813–1815, Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, ISBN 0-8369-5637-0

- Smith, Gene A. (2004), A British eyewitness at the Battle of New Orleans, the memoir of Royal Navy admiral Robert Aitchison, 1808–1827, New Orleans: The Historic New Orleans Collection, ISBN 0-917860-50-0

- Smith, Sir Harry "Various Anecdotes and Events of my Life – The Autobiography of Lt. Gen. Sir Harry Smith, covering the period 1787 to 1860" First published in 2 volumes, edited by G.C. Moore, London (1901)

- Smith, Zachary F. (1904), The battle of New Orleans, Louisville, Kentucky: John P. Morton & Co.

- Stanley, George F. G. (1983), The War of 1812 – Land Operations, MacMillan & National Museum of Canada

- Stoltz, Joseph F., The Gulf Theatre, 1813-1815. (https://josephfstoltz.com/new-orleans-campaign/)

- Stoltz, Joseph F. A Bloodless Victory: The Battle of New Orleans in History and Memory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017.

- Surtees, W. (1996) [1833], Twenty-Five Years in the Rifle Brigade (Reprint ed.), London: Greenhill Books, ISBN 1-85367-230-0

- Ward, John William (1962), Andrew Jackson: Symbol for an Age, New York: Oxford University Press

Further reading

- "Battle of New Orleans". Living Louisiana. Cox. February 20, 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2018 – via YouTube.

- "The Battle of New Orleans: 197th Anniversary – January 6-8, 2012 – Chalmette, La". Louisiana Hometown Network. December 19, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2018 – via YouTube.

- "The Battle of New Orleans". Louisiana State Exhibit Museum. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- "The Battle of New Orleans – Popular Myths and Legends; And a Few Others Thrown in as well!". 93rd Sutherland Highland Regiment of Foot Living History Unit. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- Bradshaw, Jim (July 28, 2011). "Battle of New Orleans". In Johnson, David. Encyclopedia of Louisiana. New Orleans, Louisiana: Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- "Documents, Artifacts, and Imagery: Instructions to Major-General Sir Edward Pakenham for the New Orleans Campaign". War of 1812 Magazine. No. 16. The Napoleon Series. September 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- Gayarré, Charles (1867). "Chapter X: 1814‑1815". History of Louisiana. New York: William J. Widdleton. pp. 441–510.

- Kendall, John (1922). "Chapter VI: The Battle of New Orleans". History of New Orleans. Chicago and New York: The Lewis Publishing Company. pp. 91–109.

- King, Grace (1926). "Chapter XI: The Glorious Eighth of January". New Orleans: The Place and the People. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 211–251.

- Latour, Major A. Lacarriere (1912). "Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814-15". Louisiana Historical Quarterly. Louisiana Historical Society. pp. 143–153.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1912). "The Battle of New Orleans". In Halsey, Francis W. Great Epochs in American History: Described by Famous Writers from Columbus to Roosevelt. New York and London: Funk & Wagnalls Company. pp. 102–112. OCLC 599099.

- Williams, Walter (May 17, 2012). "The Battle of New Orleans". Dreamsite Productions. Retrieved July 8, 2018 – via YouTube.

- Zimmerman, Thomas (2009). "The Battle of New Orleans, December 1814 – January 8, 1815". BattleofNewOrleans.org. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

-2.png)