Basso profondo

| Voice type |

|---|

| Female |

| Male |

Basso profondo (Italian: "deep bass"), sometimes basso profundo or contrabass, is the bass voice subtype with the lowest vocal range.

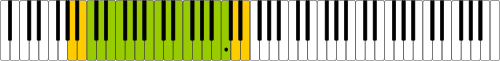

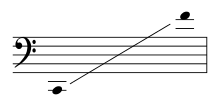

While The New Grove Dictionary of Opera defines a typical bass as having a range that is limited to the second E below middle C (E2),[1] operatic basso profondos can be called on to sing low C (C2), such as in the role of Baron Ochs in Der Rosenkavalier. Often choral composers make use of lower notes, such as G1 or even F1; in such rare cases the choir relies on exceptionally deep-ranged basso profondos termed oktavists or octavists, who sometimes sing an octave below the bass part.

Definition

According to the Italian definition, any singer with an E♭2 in fortissimo is a basso profondo. Italian composers considered basso profondos basses with "large" voices with a range of E2 to E4, lower than typical basses. Although a basso profondo obviously requires the ability to sing notes in a lower register, more importance is placed on the quality of "largeness", or resonance and sonority.

A historical reference of the basso profondo range was published in Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Dictionnaire de musique (1775), which states: "Basse-contres – the most profound of all voices, singing lower than the bass like a double bass, and should not be confused with contrabasses, which are instruments."[2]

Russian composer Pavel Chesnokov divides the bass section into these groups:

- baritones

- light basses

- strong basses

- strong basses with a good low register

- oktavists with medium range, power and a soft sound

- strong and deep oktavists

Groups 5 and 6 are considered basso profondos.

Oktavist

An oktavist is an exceptionally deep-ranged basso profondo, especially typical of Russian Orthodox choral music. This voice type has a vocal range which extends down to A1 (an octave below the baritone range) and sometimes to F1 (an octave below the bass staff) with the extreme lows for oktavists, such as Mikhail Zlatopolsky or Alexander Ort, reaching C1.

Slavic choral composers sometimes make use of lower notes such as B♭1 in the Rachmaninoff All-Night Vigil, G1 in "Ne otverzhi mene" by Pavel Chesnokov or F1 in "Kheruvimskaya pesn" (Song of Cherubim) by Krzysztof Penderecki, although such notes sometimes also appear in repertoire by non-Slavic composers (e.g. B♭1 appears in Gustav Mahler's Second and Eighth Symphonies). Russian composers often make no distinction between a basso profondo, an oktavist or a contrabass singer.

Because the human voice usually takes a long time to develop and grow, low notes often sound more resonant and full as the singer has aged considerably; thus oktavists are often older men.[3]

Sergei Kochetov, Vladimir Miller, and Mikhail Kruglov recorded a number of classic Russian folk songs and similar music, singing them in a low-pitched key to invoke the old oktavist tradition which dates back to the Tsar's court.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Owen Jander; Lionel Sawkins; J. B. Steane; Elizabeth Forbes. L Macy, ed. "Bass". Grove Music Online. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2006. ; The Oxford Dictionary of Music gives E2 to E4 or F4

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1775). Dictionnaire de musique (in French). Paris. p. 66.

- ↑ Croan, Robert (7 October 2010). "The basses of 'the Barber'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

Sources

- Smirnov, Georgy (1999). Basso Profondo From Old Russia (CD Liner notes). "The Orthodox Singers" male choir. Moscow Conservatory: Russian Season. RUS 288 158. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- Camp, Philip Reuel (2002). A Historical and Contextual Examination of Alexandre Gretchaninoff's Second Liturgy of St. John Chrysotom, Opus 29 (PDF) (PhD. Thesis). Texas Tech University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- Ritzarev, Marina (2006). Eighteenth-century Russian Music. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 255. ISBN 0-7546-3466-3. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

Further reading

- Morosan, Vladimir Choral Performance in Pre-revolutionary Russia, UMI Research Press, 1986. ISBN 0-8357-1713-5

- Rommereim, J. C., "The Choir and How to Direct It: Pavel Chesnokov's magnum opus", Choral Journal, Official Publication of the American Choral Directors Association, XXXVIII, no. 7, 1998

External links

| Look up basso profondo in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- From Basso Profondo from Old Russia on YouTube, The Orthodox Singers male choir

- oktavism.com, website dedicated to the oktavist voice