Back pain

| Back pain | |

|---|---|

| |

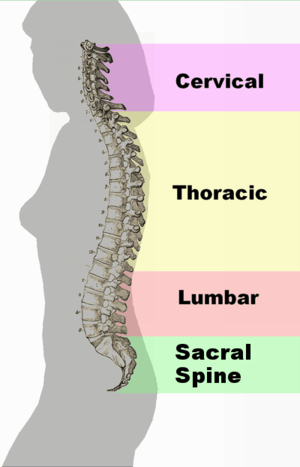

| Different regions (curvatures) of the vertebral column | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

Back pain is pain felt in the back. It is divided into neck pain (cervical), middle back pain (thoracic), lower back pain (lumbar) or coccydynia (tailbone or sacral pain) based on the segment affected.[1] The lumbar area is the most common area for pain, as it supports most of the weight in the upper body.[2] Episodes of back pain may be acute, sub-acute, or chronic depending on the duration. The pain may be characterized as a dull ache, shooting or piercing pain, or a burning sensation. Discomfort can radiate into the arms and hands as well as the legs or feet, and may include numbness,[1] or weakness in the legs and arms.

Back pain can originate from the muscles, nerves, bones, joints or other structures in the spine. Internal structures such as the gallbladder, pancreas, aorta, and kidneys may also cause referred pain in the back.

Back pain is common, with about nine out of ten adults experiencing it at some point in their life, and five out of ten working adults having it every year.[3] Some estimate up to 95% of Americans will experience back pain at some point in their lifetime.[2] It is the most common cause of chronic pain, and is a major contributor of missed work and disability.[2] However, it is rare for back pain to be permanently disabling. In most cases of herniated disks and stenosis, rest, injections or surgery have similar general pain resolution outcomes on average after one year. In the United States, acute low back pain is the fifth most common reason for physician visits and causes 40% of missed days off work.[4] Additionally, it is the single leading cause of disability worldwide.[5]

Classification

Back pain may be classified by various methods to aid its diagnosis and management. The duration of back pain is considered in three categories, following the expected pattern of healing of connective tissue. Acute pain lasts up to 12 weeks, subacute pain refers to the second half of the acute period (6 to 12 weeks), and chronic pain is pain which persists beyond 12 weeks.[6]

Causes

In as many as 85% of cases, no physiological cause can be found.[7]

There are many causes of back pain, including blood vessels, internal organs, infections, mechanical, and autoimmune causes.[8] The spinal cord, nerve roots, vertebral column, and muscles around the spine can all be sources of back pain.[8] The anterior ligaments of the intervertebral disc are extremely sensitive, and even the slightest injury can cause significant pain.[9] In osteoporosis, the bones become weaker and can develop small cracks, or fractures, in the bones, resulting in pain.[10] Arthritis in the joints of the back can also result in discomfort.[10] The synovial joints of the spine (e.g. zygapophysial joints/facet joints) have been identified as the primary source of the pain in approximately one third of people with chronic low back pain, and in most people with neck pain following whiplash.[11]

Approximately 98 percent of people with back pain are diagnosed with nonspecific acute back pain in which there is no serious underlying pathology.[12] Less than 2 percent are attributed to secondary factors, with metastatic cancers and serious infections, such as spinal osteomyelitis and epidural abscesses, accounting for around 1 percent.[13]

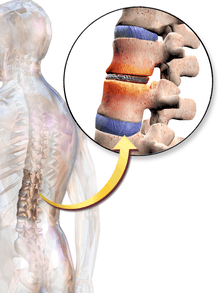

Back pain can be divided into non-radicular pain and radiculopathy. Radiculopathy occurs when there is irritation in the nerve root, causing neurologic symptoms, such as numbness and tingling. Disk herniation and foraminal stenosis are the most common causes of radiculopathy.[8] Non-radicular back pain is most commonly caused by injury to the spinal muscles or ligaments, degenerative spinal disease, or a herniated disk.[8] Spondylosis, or spinal degeneration, occurs when the intervertebral disc undergoes degenerative changes, causing the disc to fail at cushioning the vertebrae. There is an association between intervertebral disc space narrowing and lumbar spine pain.[14] The space between the vertebrae becomes more narrow, resulting in compression and irritation of the nerves.[15] There is a weak association between low back pain and facet osteoarthritis, which has been considered as a primary reason for compression of spine nerve roots as they exit the intervertebral foramen.[14]

Back pain can also be due to referred pain from another source. Referred pain occurs when pain is felt at a location different from the source of the pain. An abdominal aortic aneurysm and ureteral colic can both result in pain felt in the back.[8]

Another possible cause of chronic back pain in people with otherwise normal scans is central sensitization, where an initial injury or infection causes a longer-lasting state of heightened sensitivity to pain. This persistent state maintains pain even after the initial injury has healed.[16] Treatment of sensitization typically involves low doses of anti-depressants.[17]

Risk factors

Obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and lack of exercise can increase a person's risk of back pain.[2] People who smoke are more likely to experience back pain than others.[18] Poor posture and weight gain in pregnancy are also risk factors for back pain. In general, fatigue can worsen pain.[2]

A few studies suggest that psychosocial factors such as on-the-job stress and dysfunctional family relationships may correlate more closely with back pain than structural abnormalities revealed in X-rays and other medical imaging scans.[19][20][21][22]

Diagnosis

In most cases of low back pain, medical consensus advises not seeking an exact diagnosis but instead beginning to treat the pain.[23] This assumes that there is no reason to expect that the person has an underlying problem.[23] In most cases, the pain goes away naturally after a few weeks.[23] Typically, people who do seek diagnosis through imaging are not likely to have a better outcome than those who wait for the condition to resolve.[23]

Laboratory testing may include white blood cell (WBC) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP).[8]

- Elevated ESR could indicate infection, malignancy, chronic disease, inflammation, trauma, or tissue ischemia.[8]

- Elevated CRP levels are associated with infection.[8]

Red flags

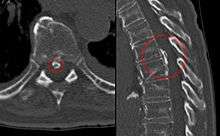

Imaging is not typically needed in the initial diagnosis or treatment of back pain. However, if there are certain "red flag" symptoms present plain radiographs (x-ray), CT scan, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be recommended. These red flags include:[24][8]

- History of cancer

- Unexplained weight loss

- Immunosuppression

- Urinary infection

- Intravenous drug use

- Prolonged use of corticosteroids

- Back pain not improved with conservative management

- History of significant trauma

- Minor fall or heavy lift in a potentially osteoporotic or elderly individual

- Acute onset of urinary retention, overflow incontinence, loss of anal sphincter tone, or fecal incontinence

- Saddle anesthesia

- Global or progressive motor weakness in the lower limbs

Prevention

There is moderate quality evidence that suggests the combination of education and exercise may reduce an individual's risk of developing an episode of low back pain.[25] Lesser quality evidence points to exercise alone as a possible deterrent to the risk of the onset of this condition.[25]

Management

The management goals when treating back pain are to achieve maximal reduction in pain intensity as rapidly as possible, to restore the individual's ability to function in everyday activities, to help the patient cope with residual pain, to assess for side-effects of therapy, and to facilitate the patient's passage through the legal and socioeconomic impediments to recovery. For many, the goal is to keep the pain to a manageable level to progress with rehabilitation, which then can lead to long-term pain relief. Also, for some people the goal is to use non-surgical therapies to manage the pain and avoid major surgery, while for others surgery may be the quickest way to feel better.[26]

Not all treatments work for all conditions or for all individuals with the same condition, and many find that they need to try several treatment options to determine what works best for them. The present stage of the condition (acute or chronic) is also a determining factor in the choice of treatment. Only a minority of people with back pain (most estimates are 1% - 10%) require surgery.

Non medical

Back pain is generally treated with non-pharmacological therapy first, as it typically resolves without the use of medication. Superficial heat and massage, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation therapy may be recommended.[27]

- Heat therapy is useful for back spasms or other conditions. A review concluded that heat therapy can reduce symptoms of acute and sub-acute low-back pain.[28]

- Regular activity and gentle stretching exercises is encouraged in uncomplicated back pain, and is associated with better long-term outcomes.[8] Physical therapy to strengthen the muscles in the abdomen and around the spine may also be recommended.[29] These exercises are associated with better patient satisfaction, although it has not been shown to provide functional improvement.[8] However, one study found that exercise is effective for chronic back pain, but not for acute pain. If used, they should be performed under supervision of a licensed health professional.[30]

- Massage therapy may give short-term pain relief, but not functional improvement, for those with acute lower back pain.[31] It may also give short-term pain relief and functional improvement for those with long-term (chronic) and sub-acute lower pack pain, but this benefit does not appear to be sustained after 6 months of treatment.[31] There does not appear to be any serious adverse effects associated with massage.[31]

- Acupuncture may provide some relief for back pain. However, further research with stronger evidence needs to be done.[32]

- Spinal manipulation is a widely-used method of treating back pain, although there is no evidence of long-term benefits.[29]

- "Back school" is an intervention that consists of both education and physical exercises.[33] A 2016 Cochrane review found the evidence concerning back school to be very low quality and was not able to make generalizations as to whether back school is effective or not.[33]

Medication

If non-pharmacological measures are not effective, medications may be tried.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are typically tried first.[27] NSAIDs have been shown to be more effective than placebo, and are usually more effective than paracetamol (acetaminophen).[34]

- Long-term use of opioids has not been tested in order to determine if it is effective or safe for treating chronic lower back pain.[35][36] For severe back pain not relieved by NSAIDs or acetaminophen, opioids may be used. Opioids may not be better than NSAIDs or antidepressants for chronic back pain with regards to pain relief and gain of function.[36]

- Skeletal muscle relaxers may also be used.[27] Their short term use has been shown to be effective in the relief of acute back pain.[37] However, the evidence of this effect has been disputed, and these medications do have negative side-effects.[35]

- In people with nerve root pain and acute radiculopathy, there is evidence that a single dose of steroids, such as dexamethasone, may provide pain relief.[8]

- Epidural corticosteroid injection (ESI) is a procedure in which steroid medications are injected into the epidural space. The steroid medications reduce inflammation and thus decrease pain and improve function.[38] ESI has long been used to both diagnose and treat back pain, although recent studies have shown a lack of efficacy in treating low back pain.[39]

Surgery

Surgery for back pain is typically used as a last resort, when serious neurological deficit is evident.[29] A 2009 systematic review of back surgery studies found that, for certain diagnoses, surgery is moderately better than other common treatments, but the benefits of surgery often decline in the long term.[40]

Surgery may sometimes be appropriate for people with severe myelopathy or cauda equina syndrome.[29] Causes of neurological deficits can include spinal disc herniation, spinal stenosis, degenerative disc disease, tumor, infection, and spinal hematomas, all of which can impinge on the nerve roots around the spinal cord.[29] There are multiple surgical options to treat back pain, and these options vary depending on the cause of the pain.

When a herniated disc is compressing the nerve roots, hemi- or partial- laminectomy or discectomy may be performed, in which the material compressing on the nerve is removed.[29] A mutli-level laminectomy can be done to widen the spinal canal in the case of spinal stenosis. A foraminotomy or foraminectomy may also be necessary, if the vertebrae are causing significant nerve root compression.[29] A discectomy is performed when the intervertebral disc has herniated or torn. It involves removing the protruding disc, either a portion of it or all of it, that is placing pressure on the nerve root.[41] Total disc replacement can also be performed, in which the source of the pain (the damaged disc) is removed and replaced, while maintaining spinal mobility.[42] When an entire disc is removed (as in discectomy), or when the vertebrae are unstable, spinal fusion surgery may be performed. Spinal fusion is a procedure in which bone grafts and metal hardware is used to fix together two or more vertebrae, thus preventing the bones of the spinal column from compressing on the spinal cord or nerve roots.[43]

If infection, such as a spinal epidural abscess, is the source of the back pain, surgery may be indicated when a trial of antibiotics is ineffective.[29] Surgical evacuation of spinal hematoma can also be attempted, if the blood products fail to break down on their own.[29]

Pregnancy

About 50% of women experience low back pain during pregnancy.[44] Some studies have suggested women who have experienced back pain before pregnancy are at a higher risk of having back pain during pregnancy.[45] It may be severe enough to cause significant pain and disability in up to a third of pregnant women.[46][47] Back pain typically begins at around 18 weeks gestation, and peaks between 24 and 36 weeks gestation.[47] Approximately 16% of women who experienced back pain during pregnancy report continued back pain years after pregnancy, indicating those with significant back pain are at greater risk of back pain following pregnancy.[46][47]

Biomechanical factors of pregnancy shown to be associated with back pain include increased curvature of the lower back, or lumbar lordosis, to support the added weight on the abdomen.[47] Also, a hormone called relaxin is released during pregnancy that softens the structural tissues in the pelvis and lower back to prepare for vaginal delivery. This softening and increased flexibility of the ligaments and joints in the lower back can result in pain.[47] Back pain in pregnancy is often accompanied by radicular symptoms, suggested to be caused by the fetus pressing on the sacral plexus and lumbar plexus in the pelvis.[47][45]

Typical factors aggravating the back pain of pregnancy include standing, sitting, forward bending, lifting, and walking. Back pain in pregnancy may also be characterized by pain radiating into the thigh and buttocks, night-time pain severe enough to wake the patient, pain that is increased during the night-time, or pain that is increased during the day-time.[46]

Local heat, acetaminophen (paracetamol), and massage can be used to help relieve the pain. Avoiding standing for prolonged periods of time is also suggested.[48]

Economics

Although back pain does not typically cause permanent disability, it is a significant contributor to physician visits and missed work days in the United States, and is the single leading cause of disability worldwide.[4][5] The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons report approximately 12 million visits to doctor's offices each year are due to back pain.[2] Missed work and disability related to low back pain costs over $50 billion each year in the United States.[2] In the United Kingdom in 1998, approximately £1.6 billion per year was spent on expenses related to disability from back pain.[2]

References

- 1 2 "Paresthesia Definition and Origin". dictionary.com. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Church E, Odle T. Diagnosis and treatment of back pain. Radiologic Technology [serial online]. November 2007;79(2):126-204. Available from: CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- ↑ A.T. Patel, A.A. Ogle. "Diagnosis and Management of Acute Low Back Pain". American Academy of Family Physicians. Retrieved March 12, 2007.

- 1 2 Manchikanti L, Singh V, Datta S, Cohen SP, Hirsch JA (Jul–Aug 2009). "Comprehensive review of epidemiology, scope, and impact of spinal pain". Pain Physician. 12 (4): E35–70. PMID 19668291.

- 1 2 Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. "2010 Global Burden of Disease Study"

- ↑ King W (2013). Encyclopedia of Pain. Springer Reference.

- ↑ van den Bosch MA, Hollingworth W, Kinmonth AL, Dixon AK (January 2004). "Evidence against the use of lumbar spine radiography for low back pain". Clinical Radiology. 59 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2003.08.012. PMID 14697378.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice. Walls, Ron M.,, Hockberger, Robert S.,, Gausche-Hill, Marianne, (Ninth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9780323354790. OCLC 989157341.

- ↑ Burke GL (2008). "Chapter 5: The Differential Diagnosis of a Nuclear Lesion.". Backache: From Occiput to Coccyx. Vancouver, BC: MacDonald Publishing. ISBN 978-0-920406-47-2.

- 1 2 Ferri, F. F. (2018). Patient Teaching Guides. In Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-28049-5

- ↑ Bogduk N (2005). Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-06014-2.

- ↑ Slipman, Curtis W.; et al., eds. (2008). Interventional spine : an algorithmic approach. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7216-2872-1.

- ↑ "Back Pain". Archived from the original on May 6, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- 1 2 Raastad, Joachim (2015). "The association between lumbar spine radiographic features and low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 44 (5): 571–585. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.10.006. PMID 25684125.

- ↑ Lavelle, W. F., Kitab, S. A., Ramakrishnan, R., & Benzel, E. C. (2017). Anatomy of Nerve Root Compression, Nerve Root Tethering, and Spinal Instability. In Benzel's Spine Surgery (4th ed., pp. 200-205). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-40030-5

- ↑ Woolf, Clifford J (2011-03-01). "Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain". Pain. 152 (3 Suppl): S2–15. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030. ISSN 0304-3959. PMC 3268359. PMID 20961685.

- ↑ Verdu, Bénédicte; Decosterd, Isabelle; Buclin, Thierry; Stiefel, Friedrich; Berney, Alexandre (2008-01-01). "Antidepressants for the treatment of chronic pain". Drugs. 68 (18): 2611–2632. doi:10.2165/0003495-200868180-00007. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 19093703.

- ↑ Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P, Solovieva S, Viikari-Juntura E (January 2010). "The association between smoking and low back pain: a meta-analysis". The American Journal of Medicine. 123 (1): 87.e7–35. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.028. PMID 20102998.

- ↑ Burton AK, Tillotson KM, Main CJ, Hollis S (March 1995). "Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and subchronic low back trouble". Spine. 20 (6): 722–8. doi:10.1097/00007632-199503150-00014. PMID 7604349.

- ↑ Carragee EJ, Alamin TF, Miller JL, Carragee JM (2005). "Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain". The Spine Journal. 5 (1): 24–35. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2004.05.250. PMID 15653082.

- ↑ Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Yu F (May 2003). "Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of low-back pain and related disability with psychological distress among patients enrolled in the UCLA Low-Back Pain Study". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 56 (5): 463–71. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00010-6. PMID 12812821.

- ↑ Dionne CE (July 2005). "Psychological distress confirmed as predictor of long-term back-related functional limitations in primary care settings". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 58 (7): 714–8. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.12.005. PMID 15939223.

- 1 2 3 4

- Consumer Reports; American College of Physicians; Annals of Internal Medicine (April 2012), "Imaging tests for lower-back pain: Why you probably don't need them." (PDF), High Value Care, Consumer Reports, retrieved 23 December 2013

- American College of Physicians (September 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American College of Physicians, retrieved 10 December 2013

- National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (May 2009), Low back pain: early management of persistent non-specific low back pain, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, retrieved 9 September 2012

- National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (13 January 2011), "ACR Appropriateness Criteria low back pain", Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, American College of Radiology, archived from the original on 16 September 2012, retrieved 9 September 2012

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT, Shekelle P, Owens DK (October 2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society". Annals of Internal Medicine. 147 (7): 478–91. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. PMID 17909209.

- "Low Back Pain". Occupational medicine practice guidelines : evaluation and management of common health. [S.l.]: Acoem. 2011. ISBN 978-0-615-45228-9.

- ↑ Patel ND, Broderick DF, Burns J, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Low Back Pain. Available at https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69483/Narrative/. American College of Radiology. Accessed Dec 12, 2017.

- 1 2 Steffens D, Maher CG, Pereira LS, Stevens ML, Oliveira VC, Chapple M, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Hancock MJ (January 2016). "Prevention of Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 176: 1–10. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7431. PMID 26752509.

- ↑ Baron, R; Binder, A; Attal, N; Casale, R; Dickenson, AH; Treede, RD (July 2016). "Neuropathic low back pain in clinical practice". European Journal of Pain. 20 (6): 861–73. doi:10.1002/ejp.838. PMC 5069616. PMID 26935254.

- 1 2 3 Stockwell, Serena (2017-05-01). "New Clinical Guideline for Low Back Pain Says Try Nondrug Therapies First". AJN, American Journal of Nursing. 117 (5). doi:10.1097/01.naj.0000516263.01592.38. ISSN 0002-936X.

- ↑ French SD, Cameron M, Walker BF, Reggars JW, Esterman AJ (April 2006). "A Cochrane review of superficial heat or cold for low back pain". Spine. 31 (9): 998–1006. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000214881.10814.64. PMID 16641776.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Wall and Melzack's textbook of pain. McMahon, S. B. (Stephen B.) (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. 2013. ISBN 9780702040597. OCLC 841325533.

- ↑ Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, Koes BW (2005). "Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD000335. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000335.pub2. PMID 16034851.

- 1 2 3 Furlan, Andrea D.; Giraldo, Mario; Baskwill, Amanda; Irvin, Emma; Imamura, Marta (2015-09-01). "Massage for low-back pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD001929. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001929.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 26329399.

- ↑ Yeganeh, Mohsen (May 1, 2017). "The effectiveness of acupuncture, acupressure and chiropractic interventions on treatment of chronic nonspecific low back pain in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 27: 11–18 – via ClinicalKey.

- 1 2 Poquet, N; Lin, CW; Heymans, MW; van Tulder, MW; Esmail, R; Koes, BW; Maher, CG (26 April 2016). "Back schools for acute and subacute non-specific low-back pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD008325. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008325.pub2. PMID 27113258.

- ↑ Staal JB, de Bie R, de Vet HC, Hildebrandt J, Nelemans P (2008). "Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low-back pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001824. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001824.pub3. PMID 18646078.

- 1 2 Sudhir, Amita; Perina, Debra (2018). Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. ClinicalKey: Elsevier, Inc. pp. 569–576.

- 1 2 Chaparro, LE; Furlan, AD; Deshpande, A; Mailis-Gagnon, A; Atlas, S; Turk, DC (27 August 2013). "Opioids compared to placebo or other treatments for chronic low-back pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD004959. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004959.pub4. PMID 23983011.

- ↑ van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, Solway S, Bouter LM (2003). "Muscle relaxants for non-specific low back pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD004252. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004252. PMID 12804507.

- ↑ Campbell's operative orthopaedics. Azar, Frederick M.,, Canale, S. T. (S. Terry),, Beaty, James H.,, Preceded by: Campbell, Willis C. (Willis Cohoon), 1880-1941. (Thirteenth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9780323374620. OCLC 962333989.

- ↑ Bradley's neurology in clinical practice. Daroff, Robert B.,, Jankovic, Joseph,, Mazziotta, John C.,, Pomeroy, Scott Loren,, Bradley, W. G. (Walter George) (Seventh ed.). London. ISBN 9780323287838. OCLC 932031625.

- ↑ Chou R, Baisden J, Carragee EJ, Resnick DK, Shaffer WO, Loeser JD (May 2009). "Surgery for low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society Clinical Practice Guideline". Spine. 34 (10): 1094–109. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a105fc. PMID 19363455.

- ↑ "Surgery For Back Pain". Retrieved June 18, 2010.

- ↑ Benzel's spine surgery : techniques, complication avoidance, and management. Steinmetz, Michael P.,, Benzel, Edward C., (Fourth ed.). Saint Louis. ISBN 9780323400305. OCLC 953660061.

- ↑ Burke, G.L., "Backache from Occiput to Coccyx" Chapter 9

- ↑ Ostgaard HC, Andersson GB, Karlsson K (May 1991). "Prevalence of back pain in pregnancy". Spine. 16 (5): 549–52. doi:10.1097/00007632-199105000-00011. PMID 1828912.

- 1 2 High risk pregnancy : management options. James, D. K. (David K.), Steer, Philip J. (4th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier. 2011. ISBN 9781416059080. OCLC 727346377.

- 1 2 3 Katonis, P.; Kampouroglou, A.; Aggelopoulos, A.; Kakavelakis, K.; Lykoudis, S.; Makrigiannakis, A.; Alpantaki, K. (July 1, 2011). "Pregnancy-related low back pain". Hippokratia. 15 (3): 205–210. ISSN 1108-4189.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Practical management of pain. Benzon, Honorio T.,, Rathmell, James P.,, Wu, Christopher L.,, Turk, Dennis C.,, Argoff, Charles E.,, Hurley, Robert W., (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9780323083409. OCLC 859537559.

- ↑ Conn's current therapy 2017. Bope, Edward T.,, Kellerman, Rick D.,, Preceded by: Conn, Howard F. (Howard Franklin), 1908-1982. Philadelphia: Elsevier. 2017. ISBN 9780323443203. OCLC 961064076.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Back and spine at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- Handout on Health: Back Pain at National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- Qaseem, Amir; Wilt, Timothy J.; McLean, Robert M.; Forciea, Mary Ann (14 February 2017). "Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 166: 514–530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367. PMID 28192789.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Back pain. |