Aztec medicine

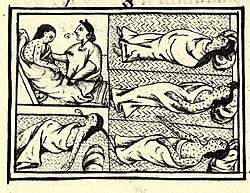

The Aztec medicine concerns the body of knowledge, belief and a ritual surrounding human health and sickness, as observed among the Nahuatl-speaking peoples in the Aztec realm of central Mexico.

The Aztecs knew of and used an extensive inventory consisting of hundreds of different medicinal herbs and plants.

A variety of indigenous Nahua and Novohispanic written works survive from the conquest and later colonial periods that describe aspects of the Aztec system and practice of medicine and its remedies, incantations, practical administration, and cultural underpinnings. Elements of traditional medicinal practices and beliefs are still found among modern-day Nahua communities, often intermixed with European or other later influences.

Medical beliefs

As with many other Mesoamerican cultures, the Aztec system recognized three main causes of illness and injury; supernatural causes (eg; displeasure of the gods, imbalance with the supernatural and natural worlds), magical causes, involving malevolent curses and sorcerers (tlacatecolotl in Nahuatl), and natural or practical causes.

Medical practices and treatment consisted of a combination of medical botany and an understanding in the supernatural.[1] Establishing a treatment for any given ailment depended first upon determining the nature of its cause, which could be the result of the supernatural or the natural. The presence of a disease could often indicate the existence of a communion with the supernatural world. The Aztecs also understood there was a balance between hot and cold in medical practice, bearing resemblance to Humorism.

The Aztecs believed that the body contained a balance of three separate entities or souls; the tonalli, the teyolia, and the ihiyotl, a balance that affected the health and life of a person.[2] The tonalli, which was commonly attributed with the disease of "soul loss", was located in the upper part of the head.[3] They believed that this life force was connected to a higher power, and the Aztec people had to make sure their tonalli was not lost or did not stray from the head. The teyolia was located in the heart. This entity has been described to be specific to the individual and stood for a person’s intelligence and memory.[1] The ihiyotl, which resided in the liver, was strongly attached to witchcraft and the supernatural. It could also leave the body but was always connected through the wind or an individual's breath, “...thus, each individual could affect other people and things by breathing on them.” [2]

The Aztecs believed in a life after death, and a life heavily influenced by the gods. They believed in Tonatiuh (heaven) on the sun reserved for the strong and the heroes after death, and another heaven on earth. The mother of gods (Teteoinam or Toci) was worshiped and followed by those in the medical field.[4] As the goddess of medicine and herbs, her image was always kept in view of medical practitioners. The Tonalamatl (religious calendar) had an impactful role on their belief system.[4] They believed that the Tonalamatl determined everything about the individual except their profession.[1] A person’s longevity, luck, sickness, and even their name was determined by the month and day they were born. The Tonalamatl was split into 13 months, each month representing a different god.[1] The Codex Vaticanus depicts the relationship between human organs and calendar signs, illustrating the magical significance certain organs or body parts held.[4]

Because the calendar had so much authority over a person's life, the day on which someone was born or got sick had great importance and usually gave reference to which god the individual had to pay respect to. It was believed that when you were sick you were being punished by the gods for your sins in some cases. Specific sicknesses were linked to individual gods and their punishments.[1] Tlaloc, the water god, was responsible for sickness related to wet and cold, such as rheumatic ailments.[3] Tlaloc also was responsible for tremor, delirium and other symptoms of alcoholism for those who abused consuming pulque. To relieve these symptoms, people would travel to mountains and rivers of significance to present the god with offerings.[4] The flayed god, Xipe Totec was responsible for skin eruptions and rashes. Common ailments included scabies, boils, and eye diseases. The way to treat this disease was to march in front of others wearing the skins from human sacrifices during the second month.[1] After they did this, Xipe Totec would cure them of their ailments. When people broke vows such as fasting or celibacy, Tezcatlipoca would induce incurable disease.[1] Macuilxochitl (Xochipilli), would send hemorrhoids, boils, and other similar diseases.[1] There were many other gods as well, each connected to their own set of sicknesses.

Illness from the gods

The Aztec believed that different gods were associated with different diseases or ailments as the Aztec in their medicine the Aztec would treat aliments and not what we think of as diseases. The god of the waters, Tlaloc, was connected with damp and cold as well as being responsible for the ailments that we know of today to be signs of alcoholism.[1] Xipe Totec, the flayed one, punished people with more physical aliments such as boils or other skin ailments. Understanding the reason for the ailments was a primary way of knowing which god sent the punishment. The ailments themselves were often not enough as multiple gods such as the god of pleasure and the god of love used similar punishments would both send venereal diseases.[1]

The Aztec are known for herbal medicine but there was a religious aspect as well. The religious side of treatment was varied based on which god issued the punishment and as well as what the ailments were. When seeking reprieve from the aliments imposed by the god of waters one would make offerings at rivers and mountains.[4] During the second month of the Aztec calendar there is a festival call tlacaxipehualiztl which was a festival honoring "the flayed one". This festival was an important event for those wishing to be cured from the aliments sent by the god. Those wishing to be cured would cover themselves in the skin of human sacrifices.[1]

Herbal medicine

| Botanical name | Aztec name | Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Atermisisa mexicana | Itztuahyatl | Weakness, colic, reduce fever; coughing |

| Bocconia frutescens | Cococxihutil | Constipation, abscesses, swelling |

| Bromelia pinguin | Mexocotl | heat blisters in the mouth |

| Carica papaya | Chichihualxo-chitl | Latex unripe fruit for rash ulcer; ripe fruit digestive |

| Casimiroa edulis | Cochiztzapotl | sedative |

| Cassia

occidentalis or Cassia alata |

Totoncaxihuitl | Astringent, purgative, anthelmintic, relieves fever, inflammation of rashes |

| Chenopodium graveolens | Epazotl | Against dysentery, anthelmintic, helps asthmatics breathe |

| Euphrobia calyculata | Cuauhtepatli; chupiri | Purgative, skin ailments, mange, skin sores |

| Helianthus annuus | Chilamacatl | fever |

| Liquidambar styracilua | Ocotzotl; xochiocotzotl quanhxihuitl | Rashes, thoothache, tonic for stomach |

| Montanoa tomentosa | Cihuapatli | Diuretic, oxytocic, cures hydropesia |

| Passiflora jorullensis | Coanenepilli | Causes sweating, Diuretic, pain reliever, poisons and snake bites |

| Perezia adnata | Pipitzahuac | Purgative, cathartic, coughing, sore throat |

| Persea americana | Auacatl; ahuaca quahuitl | Astringent, treat sores, remove scars |

| Pithecolobium dulce | Quamochitl | Astringent, causes sneezing, cures ulcers and sores |

| Plantago mexicana | Acaxilotic | Vomit and cathartic |

| Plumbago pulchella | Tlepatli; tletlematil; itzcuinpatli | Diuretic, colic, gangrene |

| Psidium guajava | Xalxocotl | Digestion, dysentery, mange |

| Rhamnus serrata | Tlalcapulin | Dysentery, bloody bowels |

| Salix lasiopelis | Quetzalhuexotl | Stops blood from rectum, cures fever |

| Schoenocaulon coulteri; Veratrum frigidum | Zoyoyatic | Causes sneezing, kills mice/lice/flies |

| Smilax atristolochiaefolia | Mecapatli | Causes sweating, diuretic, relieves joint pain |

| Tagetes erecta | Cempohualxochitl | Causes sweating, cathartic, cures dropsy |

| Talauma mexicana | yolloxochitl | Comforts heart, used against sterility |

| Theobroma cacao | Cacahuaquahuitl | Excess diarrhea, can cause dizziness |

The Aztecs had several misconceptions on the contributing factors of illness and health. For example, fever was thought to be caused by internal heat and was cured by using a purgative, digestive or diuretic to remove the heat from the body. In spite of their misconceptions of contributing factors, the medicine they used was highly effective for Aztec standards.[1] This is because they often obtained the desired results, like their purgatives successfully evacuating the body. They even succeeded, though less often, at correctly treating the ailment.This shows a strong empirical basis for their knowledge of medicine. The table to the right shows only the well agreed upon herbs in the list of hundreds that were used.[5][6]

Montezuma I had beautiful, extensive gardens near the palace that astonished the conquistadors. The gardens showed the Aztec's integration with, and dependence on nature. Many skilled craftsman and gardeners were employed to maintain and improve the gardens. Houses, paths, trees, flowers, ponds and engineered water flow were all organized by skilled masonry. Within all of this natural engineering, many medicinal herbs were maintained for actual use. Nature was a part of Aztec life, and they saw herbs as beautiful as flowers. The Spaniards admitted that their own knowledge of herbs was very limited while the Aztecs seemed to know about every herb and its use.[7][8]

See also

- Aztec use of entheogens

- Mesoamerican medicine

Sources

- Guerra, F. (1966). AZTEC MEDICINE. Medical History, 10(4), 315-338. doi:10.1017/S0025727300011455

- Millie Gimmel. Journal of the History of Ideas. Vol. 69, No. 2 (Apr., 2008), pp. 169–192

- Bernard Ortiz de Montellano. Ethnohistory. Vol. 34, No. 4 (Autumn, 1987), pp. 381–399

- Selin, Helaine, and Hugh Shapiro. “Medicine across Cultures : History and Practice of Medicine in Non-Western Cultures.” Find in a Library with WorldCat, Dordrecht ; Boston : Kluwer Academic Publishers, ©2003.

- Bernard Ortiz de Montellano. Science, New Series, Vol. 1800, No. 4185 (Apr. 18, 1975), 215-220.

- Castillo, Bernal Diaz del., et al. The discovery and conquest of Mexico. Da Capo Press, 1996.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Guerra, Francisco (Aug 2012). "AZTEC MEDICINE". Medical History. 10 (4): 315–338. doi:10.1017/S0025727300011455. ISSN 2048-8343.

- 1 2 Gimmel, Millie (2008). "Reading Medicine in the Codex de la Cruz Badiano". Journal of the History of Ideas. 69 (2): 169–192. doi:10.2307/30134035. JSTOR 30134035.

- 1 2 de Montellano, Bernard Ortiz (1987). "Caida de Mollera: Aztec Sources for a Mesoamerican Disease of Alleged Spanish Origin". Ethnohistory. 34 (4): 381–399. doi:10.2307/482818. JSTOR 482818.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Medicine across cultures : history and practice of medicine in non-Western cultures. Selin, Helaine, 1946-, Shapiro, Hugh. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 2003. ISBN 9780306480942. OCLC 53984557.

- 1 2 Ortiz de Montellano, Bernard. (1975). Empirical Aztec Medicine. Science. 188. 215-20. 10.1126/science.1090996.

- ↑ “Badianus Manuscript: An Aztec Herbal, 1552.” Herbs: Friends of Physicians, Praise of Cooks, exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/herbs/badianus/.

- ↑ Castillo, Bernal Diaz del., et al. The discovery and conquest of Mexico. Da Capo Press, 1996.

- ↑ Aztec Herbal Pharmacopoeia, Part 1, www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/health/aztec-herbal-pharmacopoeia-part-1.