Austria – the Nazis' first victim

"Austria – the Nazis' first victim" was a political slogan first used at the Moscow Conference in 1943 which went on to become the ideological basis for Austria and the national self-consciousness of Austrians during the periods of the allied occupation of 1945-1955 and the sovereign state of the Second Austrian Republic (1955–1980s[1][2][3]). According to the interpretation of this slogan by the founders of the Second Austrian Republic, the Anschluss in 1938 was an act of military aggression by the Third Reich. Austrian statehood had been interrupted and therefore the newly revived Austria of 1945 could not and should not be responsible in any way for the Nazis' crimes. The "victim theory" formed by 1949 (German: Opferthese, Opferdoktrin) insisted that all the Austrians, including those who strongly supported Hitler, had been unwilling victims of a Nazi regime and therefore were not responsible for its crimes.

The "victim theory" became a fundamental narrative of Austrian society. It made it possible for previously bitter political opponents – i.e. the social democrats and the conservative Catholics – to unite and to bring former Nazis back to the social and political life for the first time in Austrian history. For almost half a century, the Austrian state denied any continuity of the political regime of 1938–1945, actively kept up the self-sacrificing narrative of Austrian nationhood, and cultivated a conservative spirit of national unity. Postwar denazification was quickly wound up; veterans of the Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS took an honorable place in society. The struggle for justice by the actual victims of Nazism – first of all Jews – were deprecated as an attempt to obtain illicit enrichment at the expense of the entire nation.

In 1986, the election of a former Wehrmacht intelligence officer, Kurt Waldheim, as a federal president put Austria on the verge of international isolation. Powerful outside pressure and an internal political discussion forced Austrians to reconsider their attitude to the past. Starting with the political administration of the 1990s and followed by most of the Austrian people by the mid-2000s, the nation admitted its collective responsibility for the crimes committed during the Nazi occupation and officially abandoned the "victim theory".

Historical background

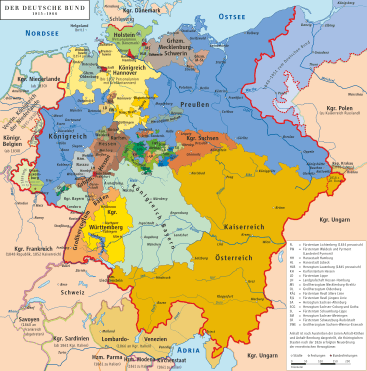

The idea of grouping all Germans into a nation-state country had been the subject of debate in the 19th century from the ending of the Holy Roman Empire until the ending of the German Confederation. The Habsburgs and the Austrian Empire favored the Großdeutsche Lösung ("Greater German solution") idea of uniting all German-speaking peoples into one-state. On the other hand, the Kleindeutsche Lösung ("Lesser German solution") sought only to unify the northern German states and not include Austria; this proposal was largely advocated by the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Prussia.[4] The Prussians defeated the Austrians in the Austro-Prussian War in 1866 which ultimately excluded Austria and the Austrian Germans from Germany. Otto von Bismarck established the North German Confederation which sought to prevent the Austrian and Bavarian Catholics from forming any sort of force against the predominantly Protestant Prussian Germany. He used the Franco-Prussian War to convince other German states, including the Kingdom of Bavaria to fight against the Second French Empire. After Prussia's victory in the war, he swiftly unified Germany into a nation-state in 1871 and proclaimed the German Empire, without Austria.[5]

After Austria's exclusion from Germany in 1866, the following year Austria sided with Hungary and formed the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867. During its existence, the German-speaking Austrians hoped for the empire to dissolve and advocated an Anschluss with Germany. Following the dissolution of the empire in 1918, the rump state of German-Austria, was created. Immediately following the publication of humiliating terms of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919) a drive for unification with Germany appeared, but its practical actions were strictly suppressed by victory states. The name "German-Austria" and union with Germany was strictly forbidden and gave way to the First Austrian Republic.[6] An independent Austrian Republic turned out to be non-viable.

After a short period of unity (1918–1920) people not recognizing themselves as a nation divided up into three armed enemy camps: working class lead by social democrats; conservative Catholic powers led by governing Christian Social Party and the Catholic Church; and supporters of the unification with Germany.[7] In 1933 the head of conservatives Engelbert Dollfuss dissolved parliament, drove social democrats out of power-holding structures, banned communists and Nazis and installed a one-party authoritarian rule of a right-wing trend.[3] In February 1934 the conflict developed into a civil war that resulted in the defeat of the left-wing forces. In July National Socialist sympathisers rebelled, killed Dollfuss, but failed to seize power.[8] During March 11–13, 1938 the Austrian state fell under the pressure of Nazi Germany and Austrian National Socialists. The absolute majority of Austrians sincerely greeted the annexation to Germany. Only some solitary pieces of evidence of a public rejection or at least indifference to Anschluss remained, mainly in rural areas.[9] Despite there were about half a million people in the capital including thousands of Jews, thousands of "Mischlinges" and political opponents who had reasons to fear Nazi repressions, there was no active resistance to the anschluss.[9]

Austrian Germans rather supported the advent of a strong power capable to prevent another civil war and to withdraw the humiliating Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye than unification with the northern neighbour.[9] Nearly all the Austrians expected that the new regime would have quickly restored a pre-Depression standard of living; the major part of population waited for the "solution" of the odious Jewish question.[9] Antisemitism, as one of the national strains, flourished in Austria more than in any other German-speaking land:[11] since 1920 parties with openly antisemitic programs has been ruling the country.[12] Pogroms that started in Vienna and Innsbruck simultaneously with Anschluss were not organised by Hitler agents, but Austrians themselves.[13][9] According to eyewitnesses's accounts, they excelled all the German events in cruelty and the scale of involvement of townspeople.[14][15] In May 1938 spontaneous violence changed into an organised "Aryanisation" – planned confiscation of Jew capitals in favour of Reich and German manufacturers.[16] For instance, no Jews owned any property in Linz after riots and "Aryanisation".[17] At this stage the primary aim of Hitlerite was not the holocaust in Austria, but to force Jews to emigrate outside the Reich.[14] During 1938–1941 about 126[14] or 135[18] thousand Jews escaped from Austria; nearly 15 thousand of them perished in German-occupied countries soon.[19] Starting with Dollfuss-Schuschnigg regime and after this wave of emigration Austria forever lost its scientific schools of Physics, Law, Economy, Viennese school of psychoanalysis and Werkbund architects.[20] However, apart from emigration, during 1933-1937 there was the influx of refugees from Germany.[8] The holocaust started in Austria in July 1941[19] and, on the whole, finished by the end of 1942.[21] Arrested were took off to ghettos and concentration camps in Belarus, Latvia and Poland via Theresienstadt and eventually killed.[21] At the end of the war slaughters resumed in Austria, where thousands of Hungarian Jews worked at the construction of lines of defence.[22] Extermination of Jews, treated as slaves "privatized" by the local Nazis, continued for several weeks in rural areas of Styria after Germany surrendered.[22] The case of slave-holders from Graz reached the court of British occupation powers. British field investigations resulted in 30 verdicts of death for Styrian Nazis, 24 of them were executed.[23] Totally one third of Austrian Jews perished just in 7 years (nearly 65 thousand people[21][15]); as low as 5816[15] people, including 2142[21] camp prisoners, survived till the end of the war in Austria.

The total number of deaths caused by Hitler's repressions in Austria is estimated to be 120 thousand.[24] During the two years (1940–1941) of Aktion T4, 18269 mentally ill people were killed in Hartheim castle alone.[25] Practically all of the Gypsy living in Austria were eliminated; moreover, no less than 100 thousand Slovenes, Czechs, Hungarians and Croatians were forced to relocate out of the Reich.[26] Apart from this, 100 thousand more people were arrested for political reasons; nearly 2700 were executed for active resistance and nearly 500 perished died in combat.[15] Austrian resistance against Nazi Regime was small and produced no significant results; the overwhelming majority of Austrians actively supported the regime until its end.[15] Among 6.5 million of Austrians of all ages, 700 thousand (17% of adults[27]) were members of NSDAP. In 1942, before the number of casualties from the Reich grew to a large number, the ratio was greater: 688 thousand of Austrians (8.2% of population) were members of NSDAP. Together with their family members, 1/4 of all Austrians were involved in the NSDAP.[1] A disproportionate share of Nazi repression staff came from Austria: the region where 8% of population of Reich lived produced 14% of SS soldiers and 40% of extermination camps staff.[28][29] More than 1.2 million of Austrians fought on the side of the Axis powers.[15] During the war, 247 thousand military personnel were killed and 25-30 thousand civilians perished in allied bombings and the Vienna offensive.[24] 170 thousand Austrians returned disabled, more than 470 thousand were taken prisoner by the Allies.[24] Despite all of these losses, the actual population of Austria did not decrease during the war. The country accepted hundreds of thousands Germans escaping allied bombings; no less than a million of foreigners – war prisoners and workers from the countries of German occupation – had been working in Austria.[14] In April 1945, there were 1.65 million displaced persons in the territory of Austria.[24]

Moscow Declaration

The term "the first victim of Germany" as applied to Austria, first appeared in English-speaking journalism in 1938, before the beginning of the Anschluss.[30] It appears in the Soviet literature in 1941, after German invasion to the USSR[31] (Soviet authors called Spain "the fascism's first victim", implying combined aggression of Italy and Germany, while Austria was assigned a role of "Hitler's first victim"[32]). On February 18, 1942 Winston Churchill said in his speech to Austrian emigrants: "We can never forget here on this island that Austria was the first victim of Nazi aggression. The people of Britain will never desert the cause of the freedom of Austria from the Prussian yoke".[33][34]

The British initiative

The Allies started to discuss the postwar destiny of Austria in 1941. On December 16 Stalin reported to Anthony Eden his plan of German break up: Austria should have become an independent state again.[35] British, having no plans for such a distant future, had nothing against. During 1942–1943 the attitude of the Allies to the Austrian question changed: leaders of the USSR have not suggested any new schemes, while British seriously took Austrian future.[36] On September 26, 1942 Eden read out Churchill's plan of creation of a "Danube confederation" composed of former Austria, Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia – a vast buffer state that would have separated Western Europe from the USSR.[37][38] In the Spring of 1943 a 34 year old analyst of the Foreign office Geoffrey Harrison made a project of the post war organisation of Austria, which became an official British policy in the Austrian question.[39] As Harrison thought, recreation of an independent but weak Austria within the borders of the First Republic was only possible with the readiness of the Western allies to support the new state for many years long.[40] Harrison have not believed in the ability of Austrians to self-organization as well as in the probability to rise them to an armed resistance against the regime.[41] The best solution according to British point of view would have been a strong confederation of Danube states with Austria included de jure as an equal member, but de facto as a cultural and political leader.[42] It was not possible to create such a union in the post war Europe immediately; an independent Austria should have been created first, and it should have been provided political guarantees and financial support. Only afterwards a political union could have been developed step-by-step.[43]

Soviet historiography of 1970s called British project an attempt to "push through the idea of a new Anschluss".[37] As M. A. Poltavsky wrote, the Allies pursued the aim to "create a conglomeration of regions in Europe that would have become a constant seat of conflicts".[37] There are two points of view on the motives of British politicians in the contemporary western historiography.[44] The traditional one considers their actions solely as an instrument to protect British concerns and to oppose the USSR in the postwar German break up.[44] According to the alternative point by R. Keyserlingk British were mainly guided by erroneous utopian plans to foment a mass resistance against Nazi regime in Austrian lands, to disrupt German Reich from the inside and to create a convenient springboard for attack from the South.[44][45] Both the points of view support that in 1943 British as well as American politics mistakenly thought that Germany has been ready to collapse under pressure from the Soviet troops or from people's indignation from the inside of Reich.[46][47] In both cases Western allies should have urgently come to an agreement on European future with the USSR.

Text endorsements

In the end of May 1943 Harrison's plan was approved by the British cabinet,[43] but no longer than in June Vyacheslav Molotov let the Foreign Office know that any association or confederation of Danube states are not acceptable to the USSR.[44] Molotov's deputy, Solomon Lozovsky, decried such a unions calling them "the instrument of anti-Soviet politics".[44] British have not abandoned their plan, so on August 14, 1943 Eden sent the Harison's project of the "Declaration on Austria" to Moscow and Washington. The text started as "Austria was the first free country to fall victim to Nazi aggression….[43] Again, facing resistance of Soviet diplomats British started to back down. According to Soviet insistence the project lost any mentioning of association with neighbouring states and Atlantic Charter, the "Austrian nation" was replaced with an unambiguous "Austria", "Nazi aggression" – with "Hitlerite aggression".[44] But no less difficult were British negotiations with Americans.[48]

Moscow Declaration on Austria became the result of this haggling between the Ally ministers.[44] It was adopted on September 30 and published on November 1st, 1943. Despite all the edits made the phrase "the first victim" remained practically untouched: "Austria, the first free country to fall a victim to Hitlerite aggression, shall be liberated from German domination…". The text was finished with a strict reminder, which was insisted by Stalin, that Austria "has a responsibility, which she cannot evade, for participation in the war on the side of Hitlerite Germany" (full text). According to Stalin version the responsibility was not lying on shoulders of certain people, groups or parties, but the society in whole; there was no way for an Austrian to escape from collective responsibility.[38] Stalin, like Churchill, has also considered Austria to be a buffer between Soviet and Anglo-American spheres of influence, and has not been in a hurry to carry out the "export of revolution".[38] His short-term goal was to exploit the survived Austrian industry, human and natural resources; probably that's why Stalin has insisted on a more strict wording of the responsibility.[38] The authors are unlikely to have suspected "the first victim" to become Austrian national idea, which they would carefully cultivate and protect, and to determine Austrian foreign policy for many years.[49] Moreover, they haven't know that another part of the Declaration – the Austrian responsibility – would die on the vine.[49]

Response of belligerent Austrians

Different historical schools admit that defeats of 1943 gave Austrians rise to doubts about the future of Reich and helped spreading of separatist sentiments.[50] But they disagree on the role of this sentiments in history. According to the official postwar Austrian point of view defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad has started a fully fledged "national awakening".[50] Soviet historians insisted that in 1943 a new stage of resistance began in Austria, and the Moscow Declaration proved to be an "important factor that influenced Austrian nation".[51] Contemporary Western historians believe that there is no reason for drawing firm conclusions about "awakening" or "resistance".[50] It goes without saying that antihitlerite and separatist sentiments have been spreading both in Vienna and remote places of Austria, but nearly in the same degree as in other lands of Reich.[52] War defeats, Italian withdrawal from war, Anglo-American bombings, stream of refugees and prisoners facilitated this, but Western historians deny the influence of Moscow Declaration. Evan Bukey admits that the Declaration inspired the Austrian underground, but neither increased their forces nor helped to spread separatist sentiments.[53] R. Keyserlingk writes that the Declaration brought the Allies more harm than good.[54] The operation of British propagandists among Austrian soldiers at the Italian front failed :[55] the Moscow Declaration has not influenced the fighting spirit of German troops and, probably, merely was a great help for Goebbels' counterpropaganda.[54]

Austria was far behind the lines of belligerent Germany and the reaction of Austrian civilians on the Moscow Declaration was dual.[53] On one hand, people made a false conclusion that the status of "the first victim" will help Austria to avoid allied bombings.[53] On the other hand, "Moscow" in the title was unmistakably associated not with western allies, but with uncompromising Bolshevism.[53] People, in whole, were indifferent to the news and did not support any anti-Hitler opposition groups.[53][2] During 1943–1944 the number of arrests increased, but 80% of arrested were foreign workers, whose number was 140 thousand in Vienna alone.[56] During 1944, as military and economical landscape has been getting worse, dissatisfaction has been increasing among Austrians too, but not with Hitler regime, but with the stream of refugees, especially Protestants, "from the North".[57] Home-level conflicts did not undermine the fighting spirit of the nation. Quite the contrary, success of the Allies and reactivation of air bombings of Austria only consolidated its population around the figure of Fuerer.[58][59] During the unsuccessful 20 July plot people of Vienna fully supported Hitler.[60]

Declaration of the slogan

On April 13, 1945 the Soviet troops captured Vienna. Two weeks later, on April 27, the Provisional Government, formed by the Soviet forces under Karl Renner, promulgated the "Proclamation of the Second Republic of Austria", which literally reprinted the text of the Moscow Declaration.[62] Renner, who had previously been an active supporter of Anschluss,[63] still considered it a historical necessity, and expressed his regret over the forced separation of Austria and Germany under the pressure of the Allies in his address to the nation. The majority of Austrians agreed with him.[64] But the proclamation of April 27, which was addressed not so much to the nationals as to victory states, stated the opposite: events of 1938 were not the result of agreement between equal parties or expression of the popular will, but the result of "an uncovered external pressure, a terrorist plot by own national socialist minority, deception and blackmail during talks, and then – an open military occupation … The Adolf Hitler's Third Reich deprived people of Austria of their power and freedom to express their will, led them to a senseless and pointless massacre, which no one Austrian has not wanted to take part in."[65][66]

The proclamation of April 27 gingerly repudiated the claim of the Moscow declaration about Austria's own contribution to its liberation: since, as the fathers of the Second Republic asserted, during 1938–1945s the Austrian statehood had been temporarily interrupted, the revived Austria should not have been responsible for crimes of "invaders".[67][68] In May–June 1945 the Provisional Government recorded this proposition in an official "doctrine of the occupation" (German: Okkupationsdoktrin).[67] All the guilt and responsibility for the crimes of occupation regime was laid at the door of Germany – the only successor of Hitlerite Reich.[67][69] The position of Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Austria on the Jewish question became a practical consequence of this doctrine: as there had not been Austrians to persecute Jews, but German occupiers, then "according to the international law Austrian Jews should submit their claims for reparations not to Austria, but to German Reich".[70] Foreign Minister of Austria Karl Gruber organized compiling and publishing of "Red-White-Red Book" in order to persuade victory states.[71][72] According to the plot of Austrian politicians the collection of real documents and "historical comments" that were thoroughly compiled with prejudice, should have persuaded the powers of victory states in a forced nature of Anschluss (that was true) and also in a mass rejection of Hitler regime by Austrians (that was not true).[71] The book was planned to be a many-volumed set. But the second volume, the "story of Austrian resistance", still was not published: according to the official version not enough archive evidences were found.[72] The authors affirmed, for instance, that in 1938 70% of Austrians had not simply been against Anschluss, but they had said to feel a "fanatic animosity" against it.[71] This is how the narrative was established to later become an ideological foundation of the postwar Austria.[73][72]

Founders of the Second Republic probably had a moral right to consider themselves to be victims of political repressions.[74] Twelve of seventeen members of the Cabinet of Leopold Figl, that headed the government in December 1945, were pursued under Dollfuss, Schuschnigg and Hitler. Figl himself was imprisoned in Dachau and Mauthausen[74] and for this reason he was insolent of emigrants who had "escaped from difficulties".[75] So this is not surprising that the narrative of "the road to Dachau" (German: Der Geist der Lagerstrasse) followed "the first victim" narrative:[76] according to this legend during their imprisonment Austrian politicians came up to agreement to stop interparty squabbles and to unite forever for the sake of building new and democratic Austria.[77] Representatives of the major parties of the First Republic – conservatives, social democrats and communists – did united, but only in the beginning of April 1945.[77] According to the contemporary point of view, the politicians were united not under a conscious choice, but under the need to survive in hardest postwar conditions and intentional pressure from the Allied occupational powers.[77] The statement about "all-nation unity" of all Austrians in cause of post-war reconstruction, that was essential for the country to survive and revive, became the third fundamental narrative. In actual fact not less important for Austria to survive was political and financial support from the USA.[78]

Evolution of ideology

Anti-fascist period

An anti-fascist spirit dominated in Austrian public politics during the first two postwar years. Propaganda of feats of the Austrian resistance proved the Allies the contribution to the defeat of Nazism, which was required from Austrians by the Moscow Declaration. The other task of anti-fascist propaganda was to find a new ideology that could be relied on by morally and financially exhausted nation.[79] Anti-fascist rhetoric, that has been forced from above, ran through the whole social life of Austria. Broken chains appeared on the coat of arms of Austria as a symbol of liberation of Austria from "foreign occupation" by Germany,[66] memorial tablets and modest temporary monuments in honour of perished anti-fascists were installed in towns[80] (the only big monument of this period, Heroes' Monument of the Red Army in Vienna, was erected due to will of the USSR).[61] Propaganda of all levels praised feats of few anti-fascist heroes, but carefully avoided the topics of Austrian Jews and extermination camps.[81] The "victim theory" of this period, that ended not later than 1949, was based on 4 statements:[66]

- Anschluss of 1938 has not been a reunion of German nation, but a violent seize of Austria by a foreign aggressor;

- 1938–1945 should be considered a period of foreign occupation;

- despite having been pursued by the occupiers, the Austrian resistance made a prominent contribution to the victory of the anti-Hitler coalition;

- Austrian soldiers of Wehrmacht were forced to serve under a threat of a cruel terror.[66]

Role of an informal ideology constructionist from the anti-fascist, openly left position was taken by the Union of Concentration Camps Prisoners (German: KZ-Verband).[82] This organisation pursued the aim to take control over the government and insisted on that only active anti-fascists could have been considered true victims of the regime, closing their doors to "passive victims" – first of all Jews.[82] Simon Wiesenthal accused KZ-Verband of continuing the "only for Aryans" practice that was accepted in Austrian parties before anschluss; Jews who returned from the camps – of copying Nazi division of inmates into "upper" and "lower" categories.[82] The position of KZ-Verband determined the contents of the first Austrian laws about helping to Nazis' victims.[82] Austria agreed not to offer them a remuneration, but just an allowance and not for everyone but to active participants of the resistance movement.[83] According to the will of social democrats and conservatives force of the law was extended to victims of Dollfuss- Schuschnigg regime (except national socialists). All the "passive victims", especially emigrants, were not eligible for the allowance.[83] The legislators followed simple interests and helped only those from whom they could expect political assistance.[79] Several thousands of survived Jews were of no interest, as opposed to hundreds of thousands of front-line soldiers and Nazis.[84]

Change of direction

Already in 1946 it became clear that left anti-fascist propaganda has not met understanding in society so not later than 1947 it fully ran out.[79][85] Prisoners, who returned from camps, were surprised to find that Austrians "forgot" about the years of Hitler regime. A patriotic upsurge appeared in the country and replaced bitter memories.[71] In 1947 the Allies began a mass liberation of captivated Austrians and Austrian government restored half a million of "less tainted" members of former NSDAP in their rights (German: Minderbelastete).[85] From that moment a political struggle for the votes of former Nazis and veterans became a governing trait of Austrian political life. Conservatives and social democrats rejected anti-fascist rhetoric, while communists, who supported it, quickly lost their political weight. In the beginning of 1947 they lost their places in government, the police closed KZ-Verband in the end of the year.[86] "February 1948" events in Czechoslovakia and threat of "export of revolution" deprived communists of all the influence.[22] Three-party coalition decreased to a classical two-party, place of the third force took the "Federation of Independents", which was created under social democrats sponsorship, – the union of former Nazis, a virtual successor of Austrian branch of NSDAP, who were banned to join "big" parties for that moment.[87] Marginalization of communists, who really have been the backbone of a not numerous Austrian resistance, meant a political defeat of anti-fascists in whole.[88][15] They failed to enter the governing elite, their past endeavours appeared to be not needed in the internal politics; they were occasionally remembered in communication with western diplomats.[88]

Party ideologists realized that anti-fascist policy was unpromising so they found the way out in a conservative propaganda of Austrian "national identity".[81] The "Book of Austria" published by the government in 1948 stated that Austria has been a country of simple, peaceful people of high culture, kind Catholics famous not for their wars or politics but for their ancient traditions.[81] The place of an internal enemy (Nazism) of the new ideology took the familiar foreign enemy – Bolshevism.[85] The image of an "innocent victim", mostly addressed to the victory states and estimated on the near pullout of the occupational troops, fitted into the internal policy well too. The "victim theory" assumed two forms: one for internal and one for foreign use.[89] Austrians still have been exploiting the slogan of the Moscow Declaration about "Hitler's first victim" in their foreign politics. But inside Austria it was transformed into the newest unifying narrative that all the Austrians, without any exception, have been the victims.[90][91] Following the political necessity all the sections of the society were sequentially included to the list of the victims. Former Nazis were included to the narrative as "victims" who have been deluded and deceived by the foreign tempter. Soon after the Federal Elections of 1949 (German: Nationalratswahl in Österreich 1949) they were officially recognized the "victims" of denazification and all of those who they have ever victimized.[92] In 1949 Rosa Jochmann, ideologist of social democrats, anti-fascist of the immediate past and former prisoner of Ravensbrück, presented the new doctrine in this way:

We all were the victims of fascism. A soldier who has come through the war in its worst form at the front was the victim. The population of the home front, who has been afraid of waiting for air-raid alarm and who has been dreaming of getting rid of bombing horror, was the victim. Those who had to leave their motherland were the victims … and finally we, unprotected victims of SS, inmates of prisons and camps, were the victims.[92]

Opfer des Faschismus waren wir alle. Opfer war der Soldat, der draussen an der Front den Krieg in seiner furchtbarsten Form erlebt hat, war die Bewolkerung, die im Hinterland voll Entsetzen auf den Kuckkuckruf wartete, um in ihre Unterstaende zu fluchten und voll Sehnsucht der Tag herbeizuwunschen, der diesen Schrecken von ihr nahm. Opfer waren jene, die die Heimat verlassen mussten, um das zumeist traurige Los des Emigranten auf sich zu nehmen, und Opfer waren schliesslich wir, die wir in Gefangnissen, Zuchthausern und Konzentrationslagern der SS ausgeliefert gewesen sind.[93]

In the time of the new order none of the truly abused groups such as Jews, Gypsies and political opponents could ever pretend to get a targeted support from the state. The society has rejected and blamed claims of these groups as an attempts to enrich themselves at the expense of all the "Nazis' victims".[92] The existence of these groups itself was unneeded and inconvenient: they reminded to the great mass of Austrians about their criminal past, so that's why they were erased from the collective memory.[92] By 1949 installation of memorials to heroes of the resistance was no longer desirable, at least at the provinces. And by the beginning of 1950s it was it was identified with an antagonistic Communist propaganda everywhere.[94] Some of the previously installed monuments were removed (e.g. common graves in KZ Ebensee and Sankt-Florian[95]), other were redesigned to replace "provocative" texts with "neutral" ones (e.g. memorial tablet in Innsbruck at the place of death of Franz Mair (Widerstandskämpfer) that was edited twice – the first time after the alleged request of German tourists, the second time – after the request of local Catholics[95]). The ideas of anti-fascists, who were "undermining the foundations" while hundreds of Austrians were performing their "sacred duty" (even if under the banners of "German occupiers"), were finally discredited and condemned.[96]

Revanche

On the contrary, war veterans got the seat of honor. In 1949-1950 veteran societies (German: Kameradschaft) appeared spontaneously all over the country.[98] For instance, by 1956 there were 56 veteran cells in an under-populated region of Salzburg. In 1952 there were 300 cells uniting 60 thousand veterans in Styria.[98] This societies have had an ultimate support of all the parties without any exception and have actively participated in local political life.[96][99] War memorials that had been erected throughout the country – from the capital to small villages – became the evidence of a full rehabilitation of Wehrmacht soldiers and SS forces. The peak of their construction was in the same 1949–1950s.[96][91] Mass meetings of veterans became a commonplace. The ban of wearing of German military uniform, that had been introduced in 1945, was demonstratively violated everywhere.[100] The Provisional Government misgivingly watched at the rise of nationalism: on the one hand, veterans in Nazi uniform provoked the occupational powers.[100] On the other hand, Austrian veterans made common cause with German ones (the border of Austria and the FRG was practically open) threatening a new, spontaneous Anschluss that was disturbing for the Allies too.[101] The government tried how it could to prevent the statements of pro-German activists in the federal media,[100] but did not dare to persecute their political wing – the "Union of Independent".[102] On the presidential elections of 1951 the former Nazi and the candidate of the "Union" Burghard Breitner got more than 15% of votes.[97]

In 1955 Austrians managed to solicit the Allies to exclude the provisions of Austrian responsibility for Hitlerite crimes from the Austrian State Treaty. Earlier Israel has renounced its claims to Austria.[103] After the sovereignty had been recovered and the occupational troops been pulled out, the Austrian conservative rhetoric reached its climax.[104] At last Austrians could openly express their attitude to the results of WWII: according to the "victim theory" of that period (1955-1962) the invasion of the victory states in 1945 was not a liberation, but a hostile occupation that superseded Hitlerite one.[104] From this point of view Austria had been a "victim" not only of Hitler, but also of the victorious occupiers.[105] The first of federal politicians to express this opinion in public was Figl during the celebrations of signing the Austrian State Treaty.[104]

Austrian politicians thought that ultra-right forces would have quickly lost their influence in an independent state, but despite their estimations the veteran movement increased rapidly and took the role of a defender of the society from the "red threat"[106] and a new commentator of the state ideology.[91] The distinction between the Austrian Armed Forces and the veteran societies, as it seemed to foreign observers, was smoothed away: employed officers openly wore Hitlerite uniform,[107] the veterans claimed to have a right to carry arms and to create an armed volunteer corps.[108] Social democrats, who created the "Union of Independent" in 1949, were the first to realize the threat, but conservatives from the ÖVP prevented the attempts to restrain the veterans.[109] Only in 1960 conservatives became concerned with an unpredictable behaviour of people dressed in the Wehrmacht uniform so Austria banned to wear Swastika.[109]

Conciliation

Fifteen-year age of conservative governments of Leopold Figl and Julius Raab passed under the sign of a full and uncompromising denial of guilt of Austria and the Austrians in Hitlerite crimes.[104] In 1961 the power passed to the socialist government under Bruno Kreisky. Over the next several years (not later than 1962[110]-1965[111]), as the first post-war generation entered the social life, the state ideology softened. A process to return the Resistance heroes to the public conscience began. It was followed by a rival campaign of ultra-rightists with an opposite spirit.[112] A political dialogue inside the firmly consolidated, inflexible ruling elite still was not possible: protesting sentiments manifested in cultural and scientific spheres.[113] In 1963 historians and anti-fascists founded the national archive of the Resistance, in 1964 the federal government approved the construction of the first memorial for the victims of concentration camps in Mauthausen.[111] The society interpreted these cautious steps as a challenge for the dominating ultra-right views[114] and resisted "the attempts to blacken the past". During the shooting of a musical film The Sound of Music, the plot of which unfolds just in times of the Anschluss and after, the authorities of Salzburg forbade the producers to decorate the streets of the town with Nazi symbols insisting that "there had never been Nazis in Salzburg".[115][2] They retreated only after the producers threatened to use the true newsreels of the Nazi processions in Salzburg.[115][2] The film had a worldwide success, but failed in Austria.[115]

The death of 67-year old anti-fascist Ernst Kirchweger, beaten on March 31, 1965 during the demonstration against Nazi professor Taras Borodajkewycz catalysed the changes.[111][116] The following demonstrations of protest were unexpectedly supported by all the federal-level politicians[111] The elite no longer had need for the ultra-rightists services. Moreover, being afraid of a spontaneous movement to authoritarian dictatorship, the elite preferred to distance themselves from ultra-rightists.[111] In the same year the first memorial for anti-fascists constructed by the federal powers was opened in Hofburg.[111] By the beginning of 1970s the "victim theory" has mutated again. Anti-fascists have been returned to the official pantheon, but honouring of the Wehrmacht soldiers has still prevailed.[112] Open anti-Semitism surrendered its positions slowly: according to the 1969 poll the genocide of Jews has been firmly approved by 55% of FPÖ electorate, 30% of ÖVP electorate and 18% of SPÖ electorate (the question was "Do you agree that during 1938-1945 the Jews got their comeuppance?"; the results of the "firmly agree" answer are given here[117]); by 1985 these proportions decreased by 45%, 25% and 16% respectively.[117] All the parties have indulgently looked at the "everyday life" fascism, and they have shaped it, intentionally or not, into legitimate and prestigious forms.[117]

The consensus reached in 1960s was conserved during the following decade. The Protests of 1968 in Vienna, jokingly called a "tamed revolution" (German: Eine Zahme Revolution), had no consequences.[118] The postwar generation of Austrians, as compared to Germans of the same age, has appeared to be passive and has not tried to review the past in the same active manner; it has not directed politicians, but followed them.[119] The ruling social democrats, with the knowledge of Kreisky, continued both secret and obvious cooperation with former Nazis.[118] Episodic protests against Nazi officials gave no results. In 1970 a minister of Kreisky's government, former Untersturmführer of SS Johann Öllinger, was exposed by the West German press and had to resign.[120] Instead Kreisky (Jew himself, who escaped to Sweden in 1938[118][69]) has appointed another former Nazi Oskar Weihs.[120] In 1975 the case of a political ally of Kreisky, FPÖ president Friedrich Peter, who had been a chastiser in the 1 SS Infantry Brigade during the war ages, put a period.[121] Politicians have solidly supported Peter and condemned Simon Wiesenthal who had prosecuted him. According to the polls this line was supported by 59% of Austrians.[122] Kreisky blamed Wiesenthal for aiding and abetting Gestapo and called Austrians to reconciliation – all of them, as chancellor said, have been the Nazis' victims.[120] The limit of criticism was discovered.[121]

Practical implementation

End of denazification

Denazification in Austria in comparison with other counties was soft and smooth: there was nothing like demonstration reprisals overflowing Greece, or political repressions in the East Europe and Yugoslavia.[123] Researchers pick out 3 or 4 stages of denazification:

- April – May 1945: occupational powers of the victory states exclusively conducted lustration and criminal prosecution of former Nazis;

- May 1945 – February 1946: Austrian "people's courts" (German: Volksgericht) worked with them simultaneously;

- February 1946 – May 1948: Austrian powers carried out denazification alone.[124]

During the whole period "people's courts" tried 137 thousand cases and passed 43 capital sentences.[125]

Americans were those who conducted denazification firmly and consistently:[126] the bigger part of 18 thousand prosecuted Nazis was convicted in their sector.[127] During the whole period of the occupation Soviet powers arrested and prosecuted approximately 2000 Austrians, 1000 of them was taken off for trials and penal consequences to the USSR, about 200 were executed (for "espionage", as a rule). Much more Nazis were detained by the Soviet powers and then handed to Austrian authorities.[128] In the beginning the Soviet powers stood for whitewashing of the "less tainted" Nazis with hope that they would have helped to reinforce the Austrian communist party resources.[127] But after having been defeated at the November elections in 1945 the Soviet powers abandoned the idea to "export the revolution" to Austria and no more relied on the Austrian communist party.[127] The British sector of occupation, Carinthia, was the one with the biggest part of Nazis within the population. During the elections of 1949 rehabilitated Nazis made 18,8 % of Carinthia electorate; 9.9% in Vienna and just 8.7% in Lower Austria and Burgenland.[129] Tensions between special services, that prosecuted Hitlerites, and economic powers, that actively recruited Nazi managers, were never ending in the British sector.[130] Mass lustration and after-war restoration appeared to be incompatible: there was not enough spotless people to fill all the urgent vacancies.[131][130] One third of judges in "people's courts" were former Nazis;[132] 80%, according to the Soviet information, formed the gendarmerie of the British sector.[133] Austrian powers have regularly reported about "full denazification" of one or another department, but in reality the "cleaned out" Nazis just were transferred from one position to another.[133] Parties, including Communists, have actively accepted Nazis under the patronage and protected them from the occupational powers and rival parties using the principle "do not touch ours or we will attack yours".[75]

After the Cold War has started the Austrian government used the dissension between the former Allies and compelled the right to reconsider the outcome of denazification.[131] In May 1948 it was factually discontinued and a 9-year "period of amnesties" of former Nazis started.[127] The victory states preferred civil peace and stability to righting a wrong and secretly agreed with Austrian activities.[134][131] In 1955 "people's courts" were dismissed, Nazis' cases were passed to courts of general jurisdiction, that in 1960 become notorious for verdicts of not guilty in resonant cases.[125] In mid-70s the prosecution of Nazis was officially stopped.[125]

Suppression of the restitution

In the second half of 1945 about 4500 survived Jews returned to Vienna.[135] Renner and his government, using the "victim theory" as a cover, refused to return them their property seized during the Nazi regime. All the responsibility to help former camp inmates was laid on to the Vienna Israelite Community and "Joint".[136][135] According to the Financial Aid Law of July 17, 1945 Austria has supported only "active" (political) prisoners, but not "passive" victims of ethnic cleansing.[79] This support was limited to a modest allowance, there was no question of compensations for losses. Politicians justified this rejection of restitution both with ideological clichés and a real weakness of the state that has appeared on ruins of a defeated Reich.[92] According to Figl all that has happened in Austria had been like a natural disaster. Austria was incapable of neither recouping the losses, nor at least to ease the miseries of people who had suffered during those years.[92]

Until the end of 1990s public policy of the Second Republic in part of the restitution was defined by the "victim theory". Procrastination of legislative decisions on the matter and bureaucracy during their administration became an unwritten practical rule. The first to formulate it was the Minister of Internal Affairs Oscar Helmer (one of few politicians who have admitted the responsibility of Austrians) in 1945: "Ich bin dafür, die Sache in die Länge zu ziehen" ("I think that this question should be dragged out").[137] All the legislative decisions on the restitution were passed only under the pressure of the allied occupational powers and later – after 1955 – by the US and Jewish social organizations.[138] Austrian legislation has developed by leaps from one foreign policy crisis to another.[139] In the beginning Austrians resisted and tried to discover another consensual decision, haggled for mutual concessions,[141] and then silently sabotaged the decision.[142] Satisfaction of legislative initiatives to recognise rights of one or another group has only depended on a political weight of its activists:[143] half the century long the priority to get pensions and allowances was given to Wehrmacht veterans. Jews and Gypsy got a formal recognition in 1949,[144] medical crimes victims – only in 1995, homosexuals and asexuals – in 2005.[145]

As a result, Austrian law that regulated the restitution turned out to be a complicated and controversial "patchwork quilt" made of multitude of acts on separate cases.[138] The law of 1947 about social assistance to the victims of repressions had been corrected 30 times during 50 years.[146] For some incidental points like the restitution of confiscated property Austrians formed a fair and full-fledged legal basis as early as 1947. The other ones, like the lost rights to rent apartments,[148] were left without any decision.[149] All these laws referred not to public law, but to private civil law.[138] Plaintiffs were obliged to prove their rights in Austrian civil courts that had an adverse policy (except a short period in the end of 1940s).[138][150] Even when the federal government had a fair will to settle another dispute,[152] the state apparatus had no time to try all the claims.[142] Probably neither politicians nor ordinary officials have not realised the real scale of Hitler repressions.[142]

Rewriting the history

For the Second Republic to survive meant to make Austrians realize their own national identity, that only was to create.[76][153] As far back as the 1940s, a new, own history of Austria had been urgently composed to satisfy this purpose: it introduced into existence a special Austrian nation that differed from the German one.[76] Hero's pantheon of this history was made of people that had no connection with Germany within the 20th century, i.e. Leopold the Glorious or Andreas Hofer.[154] In 1946 the 950-year anniversary of the ancient name of Austria (German: Ostarrichi) was right on the button. As Austrians formed from a set of ancient nations then, according to Austrian historians, they were not Germans genetically[155] Religion was also different: Austrians are mainly Catholics, Germans – Protestants. The consensual opinion of Austrian scientists stated that a common language could not be the determining factor.[155]

During the first postwar decades historical science of Austria, like the society in whole, was separated into two-party columns – conservative and social-democratic,[156] who together wrote the consensual ("coalitionist", German: Koalitionsgeschichtsschreibung) history under administration of the party supervisors.[157] Probably there was no alternative during those years: simply no humanitarian or ideologist schools existed outside party camps.[158] Both the schools fabricated the contemporary history in their own way, supporting the all-nation "victim" narrative.[159] Conservative historians hid Leopold Kunschak's anti-Semitism, social democrats were silent about Renner's sycophancy before Stalin and Hitler.[159] The competing groups have never tried to expose each other, they continued to mutually respect the party legends and taboos for 3 decades.[160] Anton Pelinka thought that denying and silencing the historical reality has allowed for the first time in the history to consolidate the society and to heal the wounds of the past.[160]

In 1970s the historians, following the political order, focused on investigations of the interwar period; the Nazi governing was interpreted as absolution from sins of the First Republic and still within the boundaries of the "victim theory".[121] Authors of the standard "History of Austria" (1977) Gorlich and Romanik stated that the WWII belonged to the world history, it was not the Austrian war because Austria as the state has not participated in it.[161] Along with it Austrian patriots have known that the path to Austrian statehood revival laid through the Hitler's defeat.[161] Austrian own history was considered apart from common German one;[157] by 1980 the belief that a special, "not German" national identity of Austrians has existed became firmly established in science.[157] Austrian lineage of Odilo Globocnik, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Adolf Eichmann and other Nazi criminals was suppressed: the historians called them German occupiers.[162] The only existing (as of 2007) monograph about denazification in Austria (Dieter Stiefel, 1981) blamed it as an unfounded and incompetent intervention of the victors into home affairs.[163] Left-wing historians, in their turn, criticised the Allies for supposed suppression of a spontaneous anti-fascist movement, which had no appreciable influence in the reality.[163]

School syllabi

One of the methods to consolidate the ideology became school syllabi,[164] where the "victim" narrative was closely interwoven with the narrative about a special, not-German identity of Austrians.[165] The highest goal of Austrian school system became a patriotic education in a spirit of a national union that was worth forgetting the immediate past and forgiving the past sins of all the compatriots.

Textbooks presented the Anschluss as an act of German aggression against innocent "victim" and methodically shifted blame to other countries, who gave Austria up during the hard times.[166] The first textbooks blamed the western countries for appeasement of Hitler,[166] in 1960s the USSR temporarily became the main villain whom Austrians fought against in a just war.[167] Until 1970s the existence of Austrian movement for the Anschluss as well as Austrian Nazism was denied: according to the textbooks the society and its powers were a solid mass, every member of which equally was a "victim" of foreign forces.[166][168] Authors of 1955 reading book held the Anschluss back: Austria was literally presented as a victim of German military aggression, just like Poland or France.[166] Books of 1950s and 1960s mentioned the Holocaust rarely and in a reduced form of a minor episode.[169] The topics of a traditional Austrian anti-Semitism and its role in the events of 1938-1945 were never discussed; from the authors' point of view the prosecution of Jews had been an exclusive consequence of Hitler's personal animosity.[169] In 1960s a typical cliché of Austrian school programmes was an indispensable comparison of the Holocaust and Hiroshima or sometimes Katyn massacre. But the description of the catastrophes in Hiroshima and Nagasaki took more place than the description of the events inside Austria itself.[170] School impressed the idea that the Allies have not been any better than Axis powers, and Nazi crimes have not been something extreme.[170]

The first textbooks to give a counter-narrative were published in Austria only in 1982 and 1983. Authors for the first time discussed the problem of anti-Semitism in their contemporary society and were first to admit that Hitlerite anti-Semitism had national, Austrian roots.[169] The other textbooks of 1980s continued to diligently reproduce the "victim" narrative. They mentioned the existence of the concentration camps, but their description was reduced to just a political prosecution of a political enemies of Hitler;[171] the books considered the camps as a place where consolidation of the national elite has happened, a personnel department of the Second Republic in its own way.[167] The Holocaust was mentioned but was never classified as genocide; there were no absolute figures of exterminated people: Austrian school invented the "Holocaust without Jews".[172] Only in 1990s authors of textbook admitted the real scale of the crimes, but kept the comparsion of the Holocaust with Hiroshima. The two catastrophes still co-existed and were continuously compared, and Austrians who have done evil still were presented as passive executors of the foreign will.[173]

Historical role

All the countries that suffered under Nazi power tried more or less to forget their own past after the war.[174] Ones that had a resistance movement glorified it, forgetting about collaborationism. Others, like Austria, preferred to consider themselves victims of the foreign aggression,[174][175] although Austria, itself, did have a resistance movement (The Resistance in Austria, 1938–1945 Radomír Luza, University of Minnesota Press, 1984). According to the opinion of American politologist David Art, Austrian "white lies" about being a "victim" served for the 4 most important purposes:

- For the first time in modern history the two rival political forces – conservatives and social democrats – have united on this basis. The common rhetoric of being a "victim" allowed to forget the Civil War of the 1930s; mutual silence about the sins of the past helped to establish trust relationships between the two parties. The "big coalition" of conservatives, social democrats, church and trade unions formed in 1940s and ruled the country for almost half a century;[76]

- The recognition of all the Austrians as "victims" allowed to integrate the former Nazis (1/6 of all grown-ups in the country[27]) to the social and political life;[176]

- Delimitation from the German "occupiers" was an essential thing to build Austrian national identity.[76] Austrians of 1920s-1930s considered themselves Germans and being a part of the Reich for 8 years just confirmed their beliefs.[76] Politicians of 1940s understood that so called "Austrian nation" have never existed, but they extremely needed an ideology to form a core of national identity – the "victim theory" was the one to solve the problem;[76]

- The "victim theory" allowed to postpone and delay the restitution for half a century.[155] Industrial capitals that have been taken from Jews during Hitler times and nationalized by the Second Republic became the part of an economical foundation of postwar Austria.[175]

Dismantling of the Narrative

Waldheim affair

In 1985 ÖVP nominated the former UNSG Kurt Waldheim for the federal president election.[122] During the war ages Waldheim served as an intelligence officer in the Wehrmacht on the occupied territories of the USSR, Greece and Yugoslavia. West German and later Austrian and American journalists and the WJC accused Waldheim of being a member of Nazi organizations and a passive cooperation in punitive actions in the Balkans.[177] Waldheim consecutively denied all the accusations and insisted that the campaign of defamation has been directed not towards him in person, but towards all his generation.[178] The president of WJC Edgar Bronfman acknowledged it: "The issue is not Kurt Waldheim. He is a mirror of Austria. His lies are of secondary importance. The real issue is that Austria has lied for decades about its own involvement in the atrocities Mr. Waldheim was involved in: deportations, reprisal murders, and others too painful to think about".[179] The Waldheim affair captivated the country, an unprecedented discussion about the military past developed in the press.[179] In the very beginning of it the conservatives, who absolutely dominated in Austrian media, [180] formulated the new "victim theory" that was the first in the history to apply to patriotism of Austrians.[181] From the right-wing's point of view Austria and Waldheim personally became victims of the campaign of defamation by the world Jewry, therefore the support of Waldheim should have become a task for all the patriots.[181] The questions about Hitlerite past were interpreted as an attack against patriotic feelings of Austrians; the right-wings insisted that during the war ages Austrians have behaved respectably, so digging the past up was unneeded and harmful.[181]

The electoral campaign of Waldheim was built on calls for Austrian national feelings. Waldheim won the elections in the second round of voting, but he was not able to perform his main responsibility as the president of Austria – diplomatic representation.[182] The USA and later European countries boycotted Waldheim.[182] Austria got a reputation of a promoter of Nazism and Israel foe. European organisations continuously criticised the country for the support of the Palestine Liberation Organization.[183] In order to rehabilitate the president the Austrian government founded an independent commission of historians. In February 1988 they confirmed accusations against Waldheim: while not being the direct executor or the organizer of war crimes, it was impossible for him not to know about them.[182] The direct result of Waldheim affair in home policy was the defeat of social democrats and the factual break-up of postwar two-party system.[184] Green Party has appeared on the political scene, the radical right-wing FPÖ under Jörg Haider has started to get more strength. The system of mutual taboos has collapsed, politicians no more were obliged keep silence about rivals' affairs.[184]

Left-wing opposition

A domestic opposition to the ideology represented by Waldheim has arisen far from the political power an influential media, in circles of liberal-left intellectuals.[185] During the several years the left movement have managed to attract masses. In 1992 they called off more than 300 thousand people to demonstrations against Jörg Haider.[186] Scandals around Waldheim and Haider in a university environment finished with the triumph of the liberal-left school and a full revision of the former ideological guidelines.[187] Authors of the generation of 1990s investigated the evolution of old prejudices and stereotypes (first of all anti-Semitism), disputed the role of the Resistance in the history of the country and analysed immoral, in their opinion, evasion of Austrian politicians from admitting the responsibility of the nation.[187] Attention of the explorers has switched from a personal destinies of Austrian politicians to previously unattractive campaigns against Gypsy and homosexuals.[188] Critics of this school (Gabriele Matzner-Holzer, Rudolf Burger and others) noticed that the left-wing authors have tried to judge people of the past using moral norms of the end of the 20th century, and have not tried to sort it out if it ever was possible to repent in such a criminal community (German: Tatergesellschaft) as filled with Nazism Austria of 1940s.[189]

In the same time, 1980s, the topic of Nazi crimes penetrated into the television.[190] The true Nazis' victims who reached 1980s and who were previously afraid of public speaking, started to regularly appear on the screen both as witnesses of the past and as heroes of documentaries.[190] In 1988 the memorial against wars and fascism (German: Mahnmal gegen Krieg und Faschismus) was opened under the walls of "Albertina"; in 1995 a public exhibition of the Wehrmacht (German: Wehrmachtsaufstellung) became the event of the year and started a discussion of previously untouchable topic of affairs and destinies of almost half a million Austrians who has fought on Hitler's side.[190] A change of social sentiments became the result of the Austrian media turnaround: admission of the criminal past came in the stead of its denial.[190][191] In the beginning of 1990s the collective responsibility was admitted by only a small circle of intellectuals, politicians and left-wing youth; by the mid-2000s the major mart of Austrians had gradually joined them.[191]

Acknowledgement of liability

The denial of the "victim theory" by the Austrian state and its gradual admittance of the responsibility began in 1988.[192] Austria contributed to the existing fund of help to Nazis' victims, established a new fund, for the first time in the history made payments for benefit of the emigrants, and widened the scope of legally recognised victims (first of all Gypsy and Carinthian Slovenes).[192] These actions of the state were conditioned both by the changes in Austrian society and by the unparalleled crisis in foreign politics.[192] During the whole Waldheim's (1986–1992) the international situation of Austria was getting worse; governments of the USA and Israel joined to the pressure of Jewish diasporas as they did not wanted to admit the Nazi country, which has supported Yasser Arafat and Muammar Gaddafi, to the world politics.[183]

As early as 1987 Hugo Portisch, advisor of the federal chancellor Franz Vranitzky, recommended the government to immediately and unconditionally admit the responsibility of Austria and to recant before the outcast Jews; Vranitzky concurred this opinion, but had no courage to act.[183] Only in July 1991, one year before the end of Waldheim's term, when a political influence of Vranitzky and social democrats has noticeably increased,[193] the chancellor made a public apology on behalf of the nation and admitted its responsibility (but not the guilt) for the crimes of the past.[194][175] But neither Americans nor Israelis were impressed by this cautious confession made inside the Austrian Parliament.[195] Things started to move only after Vranitzky officially visited Israel in 1993;[195] during his visit he admitted the responsibility not of the nation alone, but also the state with a condition that the conception of a collective guilt was not applicable to Austrians[175] A year later public apologies were made by the new conservative president Thomas Klestil.[175]

The "victim theory" has been fully rejected,[191] at least at the level of the supreme organs of government. Nobody has doubted the will of Vranitzky and Klestil, but sceptics doubted if the Austrian nation was ready to share their position.[195] Conservative politicians often have no desire to support this new ideology[195] and the influence of FPÖ has swiftly increased. The unification of the left and right happened only in 2000 during another crisis in foreign politics caused by the FPÖ's electoral victory.[196] This time Austria was not only under the pressure of the USA and Jewish organisations but also the European Union.[197] Unexpectedly, Austria's integration in the EU appeared to be more vulnerable than in 1980s.[197] Politicians had to make concessions once again: under the insistence of Klestil the leaders of the parliamentary parties signed another declaration on the Austrian responsibility and approved a new roadmap towards satisfying the claims of victims of Nationalist Socialism.[196] The work of the Austrian Historical Commission (German: Österreichische Historikerkommission) resulted in admission of the economical "aryanisation" of 1938–1941 as a part of the Holocaust (that was equal to unconditional consent for the restitution);[198] Under the Washington Agreement signed with Austrian government and industry, Austria admitted its debts towards Jews ($480 mln) and Ostarbeiters ($420 mln).[199] For the first time in Austrian history, this programme of the restitution was fulfilled within the shortest possible time.[196]

References

- 1 2 Uhl 1997, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 Art 2005, p. 104.

- 1 2 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 16.

- ↑ Geiss, Imanuel (1997). The Question of German Unification: 1806-1996. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 0415150493.

- ↑ James J. Sheehan (1993). German History, 1770–1866. Oxford University Press. p. 851.

- ↑ "Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Austria; Protocol, Declaration and Special Declaration [1920] ATS 3". Austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ↑ Pelinka 1988, p. 71.

- 1 2 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bukey 2002, p. 33.

- ↑ Uhl 2006, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Steininger 2008, p. 12.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 18.

- ↑ Steininger 2012, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 Steininger 2012, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 19.

- ↑ Silverman 2012, p. 143, 144.

- ↑ Bukey 1983, pp. 177,178.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 15.

- 1 2 Полтавский 1973, p. 97.

- ↑ Schwarz 2004, p. 179.

- 1 2 3 4 Полтавский 1973, p. 99.

- 1 2 3 Bischof 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ Polaschek 2002, p. 298.

- 1 2 3 4 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 23.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 21.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 22.

- 1 2 Bekes 2015, p. 308.

- ↑ Steininger 2012, pp. 15, 16.

- ↑ Pelinka 1997, p. 96.

- ↑ "Paris Statesmen Fear Austria Is Only First Victim in Germany's Plans for Europe". The New York Times. № 19 February. 1938.

- ↑ Фишер, О. И. (1941). Австрия в когтях гитлеровской Германии. Издание Академии наук СССР. p. 1.

- ↑ Полтавский 1973.

- ↑ Полтавский 1973, p. 136.

- ↑ "PRIME MINISTER CHURCHILL'S SPEECH OF ACCEPTANCE OF A TRAILER CANTEEN PRESENTED BY AUSTRIANS IN BRITAIN TO THE W. V. S.". The Times. February 19, 1942.

- ↑ Steininger 2012, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Steininger 2012, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 Полтавский 1973, p. 138.

- 1 2 3 4 Pick 2000, p. 19.

- ↑ Steininger 2012, p. 27, 33.

- ↑ Steininger 2012, p. 31.

- ↑ Keyserlingk 1990, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Steininger 2012, pp. 31–32.

- 1 2 3 Steininger 2012, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Steininger 2012, p. 36.

- ↑ Keyserlingk 1990, p. 157.

- ↑ Keyserlingk 1990, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Steininger 2012, p. 27.

- ↑ Keyserlingk 1990, p. 145.

- 1 2 Pick 2000, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 Bukey 2002, p. 186.

- ↑ Полтавский 1973, p. 135.

- ↑ Bukey 2002, pp. 186, 188, 193.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bukey 2002, p. 208.

- 1 2 Keyserlingk 1990, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Steininger 2008, p. 36.

- ↑ Bukey 2002, p. 205.

- ↑ Bukey 2002, pp. 197, 198, 206.

- ↑ Bukey 2002, p. 209.

- ↑ Keyserlingk 1990, p. 163.

- ↑ Bukey 2002, p. 213.

- 1 2 Uhl 2013, p. 210.

- ↑ Steininger 2008, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Steininger 2008, p. 44.

- ↑ Bukey 2002, p. 227.

- ↑ "Proclamation of the Second Republic of Austria (Vienna, 27 April 1945)". Le Gouvernement du Grand-Duche de Luxembourg.

- 1 2 3 4 Uhl 2006, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 Bischof 2004, p. 18.

- ↑ Uhl 1997, pp. 65–66.

- 1 2 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 25.

- ↑ Steininger 2008, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 Bukey 2002, p. 229.

- 1 2 3 Bischof 2004, p. 19.

- ↑ Steininger 2008, p. 13.

- 1 2 Steininger 2008, p. 14.

- 1 2 Pelinka 1997, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Art 2005, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 Embacher & Ecker 2010, pp. 25, 26.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 Bailer 1997, p. 104.

- ↑ Uhl 2013, p. 209.

- 1 2 3 Uhl 2006, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 4 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 31.

- 1 2 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 32.

- ↑ Bailer 1997, p. 104: «the Jewish victims could not be politically instrumentalized».

- 1 2 3 Uhl 2006, p. 44.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, pp. 24, 31.

- ↑ Riekmann 1999, p. 84.

- 1 2 Niederacher 2003, p. 22.

- ↑ Uhl 2006, pp. 43, 45.

- ↑ Uhl 2006, pp. 44, 45.

- 1 2 3 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bailer 1997, p. 106.

- ↑ Hammerstein, Katrin (2008). "Schuldige Opfer? Der Nazinalsozialismus in der Grundungsmythen der DDR, Osterreichs und der Bundesrepublik Deutschland". Nationen und ihre Selbstbilder: postdiktatorische Gesellschaften in Europa. Diktaturen und ihre Überwindung im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert. Wallstein Verlag. p. 47. ISBN 9783835302129.

- ↑ Uhl 2006, p. 50.

- 1 2 Uhl 2006, p. 53.

- 1 2 3 Uhl 2013, p. 214.

- 1 2 "Bundespräsidentenwahl - Historischer Rückblick". Bundesministerium für Inneres.

- 1 2 Berg 1997, p. 526.

- ↑ Berg 1997, pp. 530, 539.

- 1 2 3 Berg 1997, p. 530.

- ↑ Berg 1997, p. 531.

- ↑ Berg 1997, p. 533.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, pp. 15–16.

- 1 2 3 4 Berger 2012, p. 94.

- ↑ Uhl 2006, p. 46.

- ↑ Berg 1997, p. 534.

- ↑ Berg 1997, p. 536.

- ↑ Berg 1997, p. 537.

- 1 2 Berg 1997, p. 540.

- ↑ Berger 2012, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Uhl 2006, p. 56.

- 1 2 Uhl 2006, p. 57.

- ↑ Berger 2012, p. 120.

- ↑ Uhl 2006, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 Berger 2012, p. 102.

- ↑ Art 2005, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Pelinka 1989, p. 255.

- 1 2 3 Art 2005, p. 113.

- ↑ Berger 2012, p. 121.

- 1 2 3 Art 2005, p. 114.

- 1 2 3 Uhl 2006, p. 59.

- 1 2 Art 2005, p. 115.

- ↑ Deak 2006, p. 145.

- ↑ Deak 2006, pp. 138–139.

- 1 2 3 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 24.

- ↑ Deak 2006, pp. 130–131, 139.

- 1 2 3 4 Deak 2006, p. 139.

- ↑ Bekes 2015, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Pelinka 1989, p. 251.

- 1 2 Knight 2007, pp. 586–587.

- 1 2 3 Berger 2012, p. 93.

- ↑ Deak 2006, p. 140.

- 1 2 Bekes 2015, pp. 309–310.

- ↑ Deak 2006, pp. 145–146.

- 1 2 Bailer 1997, p. 105.

- ↑ Bukey 2000, p. 231.

- ↑ Helmer announced this on a closed session of the provisional government. For the first time these words were published by Robert Nite in 1988. His work has provoked a new round of political discussion about Austrian evasion from the responsibility

- 1 2 3 4 Bailer 2011, p. 308.

- ↑ Berger 2012, p. 122.

- ↑ Berger 2012, p. 100.

- ↑ For instance, in 1952 Austria made the recognition of Israel conditional on withdrawal of Israel's material charges to Austria[140]

- 1 2 3 Bailer 2011, p. 311.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, pp. 35, 36–37.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 34.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 35.

- ↑ Bailer 1997, p. 107.

- ↑ Bailer 2011, pp. 313-315.

- ↑ During 1938–1939 no less than 59 thousand apartments occupied by Jews were "aryaised" in Vienna alone. The restitution of the lost rights to rent as such was rejected by all the generations of Austrian politicians under the pretext that it should have required eviction of tens of thousands of new tenants therefore leading to mass disorders. Only in 2000 Austria agreed to refund the lost rights to rent with 7000 USD for every lost apartment[147]

- ↑ Bailer 2011, p. 309.

- ↑ Karn 2015, p. 99.

- ↑ Bailer 2011, p. 319.

- ↑ E.g. the campaign of the Austrian Ministry of Culture to return several thousand pieces of art (1966–1972)[151]

- ↑ Korostelina 2013, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Korostelina 2013, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 Art 2005, p. 108.

- ↑ Pelinka 1997, pp. 97-98.

- 1 2 3 Ritter 1992, p. 113.

- ↑ Pelinka 1997, p. 98.

- 1 2 Pelinka 1997, pp. 95, 98.

- 1 2 Pelinka 1997, pp. 99.

- 1 2 Uhl 2006, p. 48.

- ↑ Uhl 2006, p. 45.

- 1 2 Knight 2007, p. 572.

- ↑ Korostelina 2013, p. 109.

- ↑ Korostelina 2013, pp. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 Korostelina 2013, p. 139.

- 1 2 Korostelina 2013, p. 141.

- ↑ Utgaard 1999, pp. 201, 202.

- 1 2 3 Utgaard 1999, p. 202.

- 1 2 Utgaard 1999, pp. 202–206.

- ↑ Utgaard 1999, p. 204.

- ↑ Utgaard 1999, p. 205.

- ↑ Utgaard 1999, p. 209.

- 1 2 Uhl 2013, p. 208.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Karn 2015, p. 88.

- ↑ Art 2005, p. 109.

- ↑ Art 2005, pp. 118, 132.

- ↑ Art 2005, pp. 118, 121.

- 1 2 Art 2005, p. 118.

- ↑ Art 2005, p. 121.

- 1 2 3 Art 2005, p. 120.

- 1 2 3 Art 2005, p. 117.

- 1 2 3 Pick 2000, pp. 197–199.

- 1 2 Art 2005, p. 119.

- ↑ Art 2005, p. 130.

- ↑ Art 2005, p. 132.

- 1 2 Knight 2007, p. 574.

- ↑ Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 29.

- ↑ Knight 2007, p. 575.

- 1 2 3 4 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 Karn 2015, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 Embacher & Ecker 2010, p. 36.

- ↑ Berger 2012, p. 112.

- ↑ Pick 2000, p. 197.

- 1 2 3 4 Pick 2000, p. 200.

- 1 2 3 Berger 2012, pp. 116.

- 1 2 Berger 2012, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Karn 2015, p. 93.

- ↑ Karn 2015, pp. 100–101.

Sources

- Poltavsky, M. A. (1973). Дипломатия империализма и малые страны Европы (in Russian). Moscow: Международные отношения.

- Полтавский, М. А. (1973). Дипломатия империализма и малые страны Европы (in Russian). Moscow: Международные отношения.

- Art, D (2005). The Politics of the Nazi Past in Germany and Austria. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139448833.

- Bailer-Galanda, Brigitte (1997). "They Were All Victims: The Selective Treatment of the Consequences of National Socialism". Austrian Historical Memory and National Identity. Transactionpublishers. pp. 103–115. ISBN 9781412817691.

- Bailer, B (2011). "Restitution and Compensation of Property in Austria 1945-2007". New Perspectives on Austrians and World War II (Austrian Studies vol.I). Transactionpublishers. pp. 306–340. ISBN 9781412815567.

- Bekes, C.; et al. (2015). Soviet Occupation of Romania, Hungary, and Austria 1944/45–1948/49. Central European University Press. ISBN 9789633860755.

- Berg, M. P. (1997). Challenging Political History in Postwar Austria: Veterans' Associations, Identity and the Problem of Contemporary History. Central European History. 30. pp. 513–544.

- Berger, T. (2012). War, Guilt, and World Politics after World War II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139510875.

- Bischof, G. (2004). "Victims? Perpetrators? "Punching Bags" of European Historical Memory? The Austrians and Their World War II Legacies". German Studies Review. 27 (1): 17–32.

- Bukey, E. B. (2002). Hitler's Austria: Popular Sentiment in the Nazi Era, 1938–1945. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807853634.

- Bukey, E. B. (1983). "Hitler's Hometown under Nazi Rule: Linz, Austria, 1938-45". Central European History. 16 (2): 171–186.

- Deak, I. (2006). "Political Justice in Austria and Hungary after World War Two". In Ed. J. Elster. Retribution and Reparation in the Transition to Democracy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–147. ISBN 9781107320536.

- Embacher, H.; Ecker, M. (2010). "A Nation of Victims". The Politics of War Trauma: The Aftermath of World War II in Eleven European Countries. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 15–48. ISBN 9789052603711.

- Karn, A. (2015). Amending the Past: Europe's Holocaust Commissions and the Right to History. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299305543.

- Karsteiner, U. (2013). "Sold globally – remembered locally: Holocaust Cinema". Narrating the Nation: Representations in History, Media, and the Arts. Berghahn Books. pp. 153–180. ISBN 9780857454126.

- Keyserlingk, R. (1990). Austria in World War II: An Anglo-American Dilemma. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 9780773508002.

- Knight, R. (2007). "Denazification and Integration in the Austrian Province of Carinthia". The Journal of Modern History. 79 (3): 572–612. JSTOR 10.1086/517982.

- Korostelina, K. (2013). History Education in the Formation of Social Identity. Palgrave McMillan. ISBN 9781137374769.

- Monod, D. (2006). Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification, and the Americans, 1945–1953. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807876442.

- Niederacher, S. (2003). "The Myth of Austria as Nazi Victim, the Emigrants and the Discipline of Exile Studies". Austrian Studies. 11. 'Hitler's First Victim'? Memory and Representation in Post-War Austria: 14–32.

- Pelinka, A. (1988). "The Great Austrian Taboo: The Repression of the Civil War". New German Critique (43): 69–82. JSTOR 488398.

- Pelinka, A. (1997). "The Second Republics Reconstruction of History". Austrian Historical Memory and National Identity. Transactionpublishers. pp. 95–103. ISBN 9781412817691.

- Pelinka, A. (1989). "SPO, OVP and the New Ehemaligen". In Ed. F. Parkinson. Conquering the Past: Austrian Nazism Yesterday & Today. Wayne State University Press. pp. 245–256. ISBN 9780814320549.

- Pick, Hella (2000). Guilty Victims: Austria from the Holocaust to Haider. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781860646188.

- Riedlsperger, M. E. (1989). "FPO: Liberal or Nazi?". In Ed. F. Parkinson. Conquering the Past: Austrian Nazism Yesterday & Today. Wayne State University Press. pp. 257–278. ISBN 9780814320549.

- Riekmann, S. (1999). "The Politics of Aufgrenzung, the Nazi Past and the European Dimension of the New Radical Right in Austria". Contemporary Austrian Studies: The Vranitzky Era in Austria. Transactionpublishers. pp. 78–105. ISBN 9781412841139.

- Ritter, H. (1992). "Austria and the Struggle for German Identity". German Studies Review. 15: 111–129. JSTOR 1430642.

- Schwarz, E. (2004). "Austria, Quite a Normal Nation". New German Critique (93. Austrian Writers Confront the Past): 175–191.

- Steininger, Rolf (2012). Austria, Germany, and the Cold War: From the Anschluss to the State Treaty, 1938–1955. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9780857455987.

- Stuhlpfarrer, K. (1989). "Nazism, the Austrians and the Military". In Ed. F. Parkinson. Conquering the Past: Austrian Nazism Yesterday & Today. Wayne State University Press. pp. 190–206. ISBN 9780814320549.

- Uhl, Heidemarie (1997). "Austria's Perception of the Second World War and the National Socialist Period". Austrian Historical Memory and National Identity. Transactionpublishers. pp. 64–94. ISBN 9781412817691.

- Uhl, U. (2006). "From Victim Myth to Coresponsibility Thesis". The Politics of Memory in Postwar Europe. Duke University Press. pp. 40–72. ISBN 9780822338178.