Arthur M. Sackler

| Arthur M. Sackler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Arthur Mitchell Sackler August 22, 1913 Brooklyn, New York, US |

| Died |

May 26, 1987 (aged 73) New York, New York, US |

| Education | Doctor of Medicine |

| Alma mater | New York University School of Medicine |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 4 |

| Relatives |

|

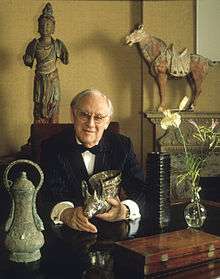

Arthur Mitchell Sackler (August 22, 1913 – May 26, 1987) was an American psychiatrist, art collector, and philanthropist whose fortune originated in medical advertising and trade publications.[1][2]

Early life and education

Born to a Jewish family[3] in Brooklyn, Sackler attended New York University School of Medicine and graduated with a M.D.[4] He also studied sculpture at The Educational Alliance and art history classes at Cooper Union.[5]

He completed an internship at Lincoln Hospital in New York City and was a resident in psychiatry at Creedmoor State Hospital.[6]

Career

Early career

Sackler began his career practicing medicine, where he specialized in biological psychiatry. In the early 1940s, he joined the medical advertising agency, William Douglas McAdams Inc.[7] From 1949 - 1954, he served as a research director at Creedmoor Institute for Psychobiological Studies.[8] Sackler collaborated on 140 papers based on neuroendocrinology, psychiatry, and experimental medicine.[6] He is also regarded as the first doctor to use ultrasound for diagnosis and identifying histamine as a hormone, and advocating for its use as an alternative to electroconvulsive therapy.[9] He is also widely credited with helping to racially integrate New York City's first blood banks. [10][11]

He was editor of the Journal of Clinical and Experimental Psychobiology from 1950-1962. In 1958, Sackler established the Laboratories for Therapeutic Research. He was director of the facility until 1983.[6] Sackler also served as chairman of the board of Medical Press, Inc. and president of Physicians News Service, Inc., as well as the Medical Radio and TV Institute, Inc.[12] He served on the board of trustees of New York Medical College where he also held a position as a research professor of psychiatry.[13]

Later career

Through direct marketing to physicians during the 1960s, he popularized dozens of medicines including Betadine, Senaflax, Librium, and Valium. He became a publisher and started a weekly medical newspaper in 1960, the Medical Tribune, which eventually reached six hundred thousand physicians.[14] Sackler's marketing of Valium helped to make it the first drug to generate $100 million in sales. As a result of his success, many other drug companies began marketing their drugs in a similar fashion.[15]

In 1981, Sackler served as vice-chairman of the first international conference on nutrition held in Tianjin, China.[16] He joined the board of directors of Scientific American in 1985.[17] In 1985, Linus Pauling dedicated his book How to Live Longer and Feel Better to him.[18] In 1997, Arthur was posthumously inducted into the Medical Advertising Hall of Fame[19], and a citation praised his achievement in “bringing the full power of advertising and promotion to pharmaceutical marketing.”

Philanthropy

Sackler built and contributed to many scientific institutions, throughout the 1970s and 1980s. His notable contributions included:

- The Sackler School of Medicine at Tel Aviv University (1972),

- The Sackler Institute of Graduate Biomedical Science at New York University (1980),

- The Arthur M. Sackler Science Center at Clark University (1985), the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences at Tufts University (1980),

- The Arthur M. Sackler Center for Health Communications, also at Tufts University (1986).[6]

Art collection

Sackler who began collecting art in the 1940s was a scholar of the arts who considered himself "more of a curator than collector" who preferred acquiring collections to individual pieces. His collection was composed of tens of thousands of works including Chinese, Indian, and Middle Eastern art as well as Renaissance and pre-Columbian pieces.[1] In a speech at Stony Brook University in New York, he discussed his idea that art and science were "interlinked in the humanities".[20] He founded galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Princeton University, the Arthur M. Sackler Museum at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology. In 1987, the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, D.C. was opened months after his death, with a gift of $4 million and 1,000 original artworks.[1][21][22] At the time of its donation, Sackler's collection of Chinese art that was donated to the Smithsonian was considered one of the largest collections of ancient Chinese art in the world according to a consultant for Asian affairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[8] Following his death, The Jillian and Arthur M. Sackler Wing of Galleries was opened at the Royal Academy of Arts,[23] as well as The Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology, was opened at Peking University in 1993.[20]

Personal life

Sackler was married three times.[4] His first two marriages ended in divorce, however, he remained married until his death to Jillian Sackler, who directs philanthropic projects in his name through the Dame Jillian Sackler and Arthur M. Sackler Foundation for the Arts, Sciences and Humanities.[24] Sackler had four children, Carol Master, Elizabeth Sackler, Arthur F. Sackler and Denise Marica.[1]

Controversy

Sackler arranged financing for his brother's purchase of Purdue Frederick in 1952. Following his death in 1987, his option on one third of that company was sold by his estate to Mortimer and Raymond Sackler,[25] who owned a separate company named Purdue Pharma, which eight years later began selling Oxycontin.[26] Critics of the Sackler family and Purdue contend that the same marketing techniques used when Arthur consulted to pharmaceutical companies selling non-opioid medications were later abused in the marketing of Oxycontin by his brothers and his nephew, Richard Sackler, contributing to the opioid epidemic. Psychiatrist Allen Frances told the New Yorker, “Most of the questionable practices that propelled the pharmaceutical industry into the scourge it is today can be attributed to Arthur Sackler.”[14][27]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Glueck, Grace (1987-05-27). "Dr. Arthur Sackler Dies at 73; Philanthropist and Art Patron". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

- ↑ Smith, J.Y. (May 27, 1987). "Arthur Sackler dies at 73". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ↑ Shapiro, Edward S. (May 1, 1995). A Time for Healing: American Jewry Since World War II. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 120. ISBN 9780801851247.

- 1 2 "Arthur Sackler Dies at 73". The Washington Post. May 27, 1987.

- ↑ "An Art Collector Sows Largesse and Controversy". The New York Times. June 5, 1983.

- 1 2 3 4 The Role of Science in Solving the Earth Emerging Water Problems. National Academies Press. September 15, 2005.

- ↑ "MAHF Inductees Arthur M. Sackler". Medical Advertising Hall of Fame.

- 1 2 Tuck, Lon (September 21, 1986). "Convictions of the Collector". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Dr. A. Sackler; Psychiatrist and Collector of Art". The Los Angeles Times. May 31, 1987.

- ↑ "Art and activism: The compass points of Elizabeth Sackler's storied career". Women in the World. 2016-01-08. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- ↑ Quinones, Sam (2015-04-21). Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9781620402504.

- ↑ The Competitive Status of the U.S. Pharmaceutical Industry: The Influences of Technology in Determining International Industrial Competitive Advantage. National Academies. January 1, 1983.

- ↑ "Arthur M. Sackler". Albuquerque Journal. May 29, 1987.

- 1 2 Keefe, Patrick Radden (2017-10-23). "The Family That Built an Empire of Pain". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- ↑ Eban, Katerin (November 9, 2011). "OxyContin: Purdue Pharma's Painful Medicine". Fortune.

- ↑ "Vitamin C heightens intelligence, nutritionists say". UPI. June 10, 1981.

- ↑ "For Sale: Scientific American". The New York Times. March 29, 1986.

- ↑ Pauling, Linus (1987). How to Live Longer and Feel Better (1 ed.). New York: Avon Books. Retrieved December 31, 2017 – via Open Library.

- ↑ "Medical Advertising Hall of Fame Inductees". Medical Advertising Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- 1 2 "Arthur M. Sackler, M.D." National Academy of Sciences.

- ↑ Karl E. Meyer, Shareen Blair Brysac (March 10, 2015). The China Collectors: America’s Century-Long Hunt for Asian Art Treasures. Macmillian.

- ↑ "Sackler Art Museum to Open at Harvard". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Arthur M. Sackler Foundation Donates Works of Art". Mount Holyoke College Art Museum.

- ↑ "Smithsonian's Sackler Gallery celebrates 25th anniversary". The Washington Post. December 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Our Incomplete List of Cultural Institutions and Initiatives Funded by the Sackler Family". Hyperallergic. 2018-01-11. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- ↑ "Elizabeth A. Sackler Supports Nan Goldin in Her Campaign Against OxyContin". Hyperallergic. 2018-01-22. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- ↑ "The Secretive Family Making Billions From the Opioid Crisis". Esquire. 2017-10-16. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arthur M. Sackler. |