Arnold Bennett

| Arnold Bennett | |

|---|---|

Bennett, from a New York Times Magazine, published 1915 | |

| Born |

Enoch Arnold Bennett 27 May 1867 Hanley, United Kingdom |

| Died |

27 March 1931 (aged 63) London, United Kingdom |

| Cause of death | Typhoid |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Novelist |

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 – 27 March 1931) was an English writer. He is best known as a novelist, but he also worked in other fields such as the theatre, journalism, propaganda and films.

Early life

Bennett was born in a modest house in Hanley in the Potteries district of Staffordshire. Hanley was one of the Six Towns that were joined together at the beginning of the 20th century as Stoke-on-Trent and are depicted as "the Five Towns" in some of Bennett's novels. Enoch Bennett, his father, qualified as a solicitor in 1876, and the family moved to a larger house between Hanley and Burslem.[1] Bennett was educated in Newcastle-under-Lyme.

Bennett was employed by his father, but the working relationship failed. He found himself doing jobs such as rent-collecting which were uncongenial. Bennett also resented the low pay: it is no accident that the theme of parental miserliness is important in several of his novels. In his spare time he was able to do a little journalism, but his breakthrough as a writer came after he had left the Potteries. At the age of 21 he left his father's practice and went to London as a solicitor's clerk.

Bennett suffered from a stammer, which Somerset Maugham described as making it "painful to watch the struggle he had sometimes to get the words out." Maugham, who also suffered from a stammer, speculated that "except for the stammer which forced him to introspection, Arnold would never have become a writer."[2]

Career

Journalism and nonfiction

In 1889 Bennett won a literary competition run by the magazine Tit-Bits and was encouraged to take up journalism full-time. In 1894 he became assistant editor of the magazine Woman. He noticed that the material offered by a syndicate to the magazine was not very good, so he wrote a serial that was bought by the syndicate for 75 pounds (equivalent to £10,000 in 2016).[3] He then wrote another. This became The Grand Babylon Hotel. Just over four years later his novel A Man from the North was published to critical acclaim and he became editor of the magazine.

In 1900 Bennett gave up the editorship of Woman and dedicated himself to writing full-time. However, he continued to write for newspapers and magazines while finding success in his career as a novelist. In 1926, at the suggestion of Lord Beaverbrook, he began writing an influential weekly article on books for the London newspaper the Evening Standard.

One of Bennett's most popular non-fiction works was the self-help book How to Live on 24 Hours a Day. His diaries have yet to be published in full, but extracts from them have often been quoted in the British press.[4]

Move to France

In 1903 Bennett moved to Paris, where other artists from around the world had converged on Montmartre and Montparnasse. Bennett spent the next eight years writing novels and plays. He believed that ordinary people had the potential to be the subjects of interesting books, and in this respect, as he himself acknowledged, he was influenced by the French writer Guy de Maupassant. Maupassant is also one of the writers on whose work Richard Larch, the protagonist of Bennett's novel A Man from the North, tries in vain to model his own writing.

Bennett's novel The Old Wives' Tale was an immediate success throughout the English-speaking world when it was published in 1908. In 1911, he visited the United States, then returned to England, where The Old Wives' Tale was hailed as a masterpiece.

Public service

During the First World War Bennett became Director of Propaganda for France at the Ministry of Information. His appointment was made on the recommendation of Lord Beaverbrook, who also recommended him as Deputy Minister of the Department at the end of the war.[5] He refused a knighthood in 1918.[6]

Osbert Sitwell,[7] noted in a letter to James Agate[8] that Bennett was not "the typical businessman, with his mean and narrow outlook". Sitwell cited a letter from Bennett to a friend of Agate's, who remains anonymous, in Ego 5:

I find I am richer this year than last; so I enclose a cheque for 500 pounds for you to distribute among young writers and artists and musicians who may need the money. You will know, better than I do, who they are. But I must make one condition, that you do not reveal that the money has come from me, or tell anyone about it.

Final years

Bennett separated from his French wife in 1921 and fell in love with the actress Dorothy Cheston (b. 1896), with whom he stayed for the rest of his life. She changed her last name to Bennett, although they were never married. They had one child, Virginia, born in London in 1926.[9]

In 1923 Bennett won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for his novel Riceyman Steps.

Bennett died of typhoid at his home in Baker Street, London, on 27 March 1931, after returning from a visit[10] to Paris where, in defiance of a waiter's advice, he had drunk tap water in a restaurant. His ashes are buried in Burslem Cemetery. His death is believed to have been one of the last occasions when the practice of spreading straw in the street to dull the sound of traffic outside the home of a dying person was carried out in London.[11][12]

Bennett's daughter, Virginia (Mary) Bennett/Eldin (1926-2003), lived in France and was President of the Arnold Bennett Society.

References to the Staffordshire Potteries in his works

Anna of the Five Towns, the first of Bennett's novels about life in the Staffordshire Potteries, appeared in 1902. The Clayhanger Family and The Old Wives' Tale also draw on experience of life in the Potteries, as did several of his other novels. In all of them the Potteries are referred to as "the Five Towns" because Bennett felt that the name was more euphonious than "the Six Towns" and omitted Fenton. The real towns and their fictional counterparts are:

The Six Towns of Stoke-on-Trent Bennett's Five Towns Tunstall Turnhill Burslem Bursley Hanley Hanbridge Stoke Knype Longton Longshaw

The name "Knype" may have been taken from the village of Knypersley near Biddulph, and/or Knypersley Hall.

Oldcastle, where Edwin Clayhanger goes to school, represents Newcastle-under-Lyme.

Axe, towards which Tertius Ingpen lives, represents Leek.

Several of Bennett's novels set in the Potteries have been made into films, for example The Card starring Alec Guinness, or television mini-series, such as Anna of the Five Towns[13] and Clayhanger.[14]

Criticism

Bennett's output was prodigious and, by his own admission, was based on maximising his income. As Bennett put it:

Am I to sit still and see other fellows pocketing two guineas apiece for stories which I can do better myself? Not me. If anyone imagines my sole aim is art for art’s sake, they are cruelly deceived.

Contemporary critics, notably Virginia Woolf, perceived weaknesses in his work. To her and other Bloomsbury authors, Bennett represented the "old guard". His style was traditional rather than modern, which made him an obvious target for those who liked to present themselves as challenging literary conventions.[15][16] Max Beerbohm criticised Bennett as a social climber who had forgotten his origins, and drew a mature and well-fed Bennett expounding, "All gone according to plan, you see" to a younger and leaner version of himself, who replies: "Yes — MY plan." Bennett in his turn regarded the Bloomsberries as decadents whose vices and general sense of life were contrary to the optimism and decency he saw in the mass of the people. In The Summing Up, William Somerset Maugham offered a more circumspect critique, "Success besides often bears within itself the seed of destruction, for it may very well cut the author off from the material that was its occasion...No better example of this can be given than Arnold Bennett. He never knew anything intimately but the life of the Five Towns in which he had been born and bred, and it was only when he dealt with them that his work had character. When success brought him into the society of literary people, rich men and smart women, and he sought to deal with them, what he wrote was worthless. Success destroyed him."

For much of the 20th century, the critical and academic reception of Bennett's work was affected by the Bloomsbury intellectuals' perception, and it was not until the 1990s that a more positive view of his work became widely accepted. The English critic John Carey had a major influence on this reassessment. Carey praises him in his book The Intellectuals and the Masses (1992), declaring Bennett his "hero" because his writings "represent a systematic dismemberment of the intellectuals' case against the masses" (p. 152).

In Queen's Quorum (1951), a survey of crime fiction, Ellery Queen listed Bennett's The Loot of Cities among the 100 most important works in the genre. This collection of stories recounts the adventures of a millionaire who commits crimes to achieve his idealistic ends. Although it was "one of his least known works," it was nevertheless "of unusual interest, both as an example of Arnold Bennett's early work and as an early example of dilettante detectivism".[17]

Quotations

- My mother is far too clever to understand anything she doesn't like.

- Any change, even a change for the better, is always accompanied by drawbacks and discomforts.

- Good taste is better than bad taste, but bad taste is better than no taste.

- [Referring to his novel The Man from the North] I put in genuine quantities of wealth, luxury, feminine beauty, surprise, catastrophe and genial incurable optimism.

List of works

Fiction

- A Man from the North 1898

- The Grand Babylon Hotel 1902

- Anna of the Five Towns 1902

- The Gates of Wrath 1903

- Leonora 1903

- A Great Man 1904

- Teresa of Watling Street 1904

- Sacred and Profane Love 1905; revised and republished as The Book of Carlotta 1911

- Tales of the Five Towns 1905 (short stories)

- Whom God Hath Joined 1906

- Hugo 1906

- The Grim Smile of the Five Towns 1907 (short stories)

- The Ghost--a Modern Fantasy 1907

- The City of Pleasure, A Fantasia on Modern Themes 1907

- Buried Alive 1908

- The Old Wives' Tale 1908

- The Glimpse: An Adventure of the Soul 1909

- Clayhanger 1910

- Denry the Audacious 1910

- Helen with a High Hand 1910 (previously serialised as The Miser's Niece)

- The Card 1911

- Hilda Lessways1911

- The Matador of the Five Towns 1912 (short stories)

- The Great Adventure: A Play of Fancy in Four Acts 1913

- The Regent: A Five Towns Story of Adventure in London 1913; published in the U.S. as The Old Adam

- The Price of Love 1914

- These Twain 1916

- The Loot of Cities 1917 (novella and seven short stories)

- The Pretty Lady 1918

- The Roll-Call 1918

- Mr Prohack 1922

- Lilian 1922

- Riceyman Steps 1923

- Elsie and the Child 1924

- The Clayhanger Family 1925, the complete trilogy consisting of Clayhanger, Hilda Lessways, and These Twain

- Lord Raingo 1926

- The Woman who Stole Everything, and Other Stories 1927

- The Vanguard 1927; published in the UK as The Strange Vanguard 1928

- The Savour of Life 1928

- Accident 1928

- Imperial Palace 1930

- Venus Rising from the Sea 1931

Non-fiction

- Journalism For Women 1898

- Polite Forces for the Drawing Room 1900

- Fame and Fiction 1901

- The Truth about an Author 1903

- How to Become an Author 1903

- The Reasonable Life 1907

- Literary Taste: How to Form It 1909

- How to Live on 24 Hours a Day 1910

- The Feast of St Friend: A Christmas Book 1911

- Mental Efficiency[18] – 1911

- Those United States 1912; also published as Your United States

- Paris Nights and Other Impressions of Places and People 1913

- The Author's Craft 1914

- Liberty: A Statement of the British Case 1914

- Over There: War Scenes on the Western Front 1915

- Books and Persons: Selections from The New Age 1908-1911) 1917

- Self and Self-Management 1918

- The Art of A. E. Rickards 1920

- Things That Have Interested Me 1921[19]

- How to Make the Best of Life 1923

- The Human Machine[20] 1925

- How to Live – 1925; consisting of How to Live on 24 Hours a Day, Mental Efficiency, and Self and Self-Management

Plays

- What the Public Wants 1909

- The Honeymoon 1911

- Cupid and Commonsense 1912

- Milestones (with E. Knoblock) 1912

- The Great Adventure 1913

- The Title 1918

- Judith[21] 1919

- The Love Match 1922

- Body and Soul 1922

- The Bright Island 1924

- A London Life 1926

- The Return Journey 1928

Opera

- Don Juan de Mañera

Film adaptations

- The Grand Babylon Hotel (1916)

- The Great Adventure (1921)

- The Old Wives' Tale (1921)

- Piccadilly (1929)

- His Double Life (1933)

- Holy Matrimony (1943)

- The Card (1952)

Television adaptations

- The Old Wives' Tale BBC 1964

- Clayhanger ATV 1976 (based on Clayhanger, Hilda Lessways and These Twain)

- Anna of the Five Towns BBC 1985

- Sophia and Constance BBC 1988 (based on The Old Wives' Tale)

Commemorations

The Omelette Arnold Bennett

While Bennett was staying at the Savoy Hotel in London the chefs perfected an omelette incorporating smoked haddock, Parmesan cheese and cream, which pleased him so much that he insisted that it be prepared wherever he travelled. The Omelette Arnold Bennett has remained a standard dish at the Savoy ever since.[22]

Newcastle-Under-Lyme, Staffordshire

A number of streets in the Bradwell area of Newcastle-under-Lyme, which neighbours Stoke-on-Trent, are named after places and characters in Bennett's works, and Bennett himself.

Memorials

Two blue plaques have been installed to commemorate Bennett. The first, at his former residence in Cadogan Square, London was placed by London County Council in 1958.[23] The second was placed in 2014 by Stoke-on-Trent City Council at Bennett's childhood home on Waterloo Road in Cobridge.[24]

A brown plaque has also been placed by the Arnold Bennett Society on Bennett's final residence at Chiltern Court in London.[25]

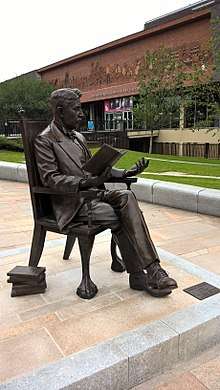

A two-metre-high bronze statue of Bennett has been placed outside the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent in June 2017 during the events marking the 150th anniversary of his birth.[26]

References

- ↑ "Listed Buildings in Stoke-on-Trent. (33a) Former home of Arnold Bennett, Cobridge". Thepotteries.org. 1972-04-19. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Morgan, Ted. Somerset Maugham. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 17. ISBN 0224018132.

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ↑ Lyons, Paul K. (2009-09-30). "The Diary Review: A Half-Crown Public". Thediaryjunction.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ Smith, Adrian (1996). The New Statesman: Portrait of a Political Weekly, 1913–1931. Taylor & Francis. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7146-4169-0.

- ↑ "2016 Annual Dinner Report". The Arnold Bennett Society. 7 April 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ↑ Sitwell, Osbert, Noble Essences: Or Courteous Revelations, Being a Book Of Characters and the Fifth and Last Volume, New York, MacMillan and Co., 1950.

- ↑ Ego 5. Again More of the Autobiography of James Agate., London, George G. Harrap and Co. Ltd (page 166), 1942.

- ↑ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ↑ "Straw for Silence". The Spectator. F.C. Westley "In a Paris hotel he drank ordinary water from a carafe. The waiter protested, 'Ah, ce n'est pas sage, Monsieur, ce n'est pas sage....'". 203. 1959. ISSN 0038-6952. OCLC 1766325.

- ↑ "Arnold Bennett: The Edwardian David Bowie?". BBC. 23 June 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ↑ My Music. Season 17. Episode 4. 4 February 1981. 7 minutes in. BBC.

One of the last times it was done was in Baker Street, 1931, Arnold Bennett's death...

- ↑ "Anna of the Five Towns". 9 January 1985 – via IMDb.

- ↑ "Clayhanger". 1 January 1976 – via IMDb.

- ↑ Seminar – "Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown" Archived 9 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Essay on the debate between Woolf and Bennett including comments on poor modern reputation of Bennett" (PDF). Filer.case.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ Queen, Ellery, Queen's Quorum: A History of the Detective-Crime Short Story As Revealed by the 100 Most Important Books Published in This Field Since 1845, Boston: Little, Brown (page 50), 1951.

- ↑ Bennett, Arnold (6 November 2007). "Mental Efficiency, and Other Hints to Men and Women" – via Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ Arnold Bennett (2008-03-05). "Things that Have Interested Me". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Project Gutenberg".

- ↑ "Project Gutenberg".

- ↑ Smith, Delia (2001–2009). "Omelette Arnold Bennett". Delia Smith / NC Internet Ltd. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Arnold Bennett Blue Plaque in London". Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ↑ "Novelist Arnold Bennett Honoured with a Blue Plaque at his Childhood Home in Cobridge". The Staffordshire Sentinel. 13 October 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ↑ "Arnold Bennett Brown Plaque in London". Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ↑ "Arnold Bennett Statue to Be Unveiled in Hanley to Mark 150th Anniversary of His Birth". The Staffordshire Sentinel. 11 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

Further reading

- F.J. Harvey Darnton, Arnold Bennett

- Margaret Drabble, Arnold Bennett: A Biography (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1974).

- Louis Tillier, Studies in the Sources of Arnold Bennett's Novels (Paris: Didier, 1949)

- E.J.D. Warrilow, Arnold Bennett and Stoke-on-Trent (Etruscan Publications, 1966)

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Arnold Bennett |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arnold Bennett. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Arnold Bennett |

- Works by Arnold Bennett at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Arnold Bennett at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Arnold Bennett at Internet Archive

- Works by Arnold Bennett at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Arnold Bennett's biography by Frank Swinnerton

- Archival material at Leeds University Library

- Arnold Bennett at Library of Congress Authorities, with 336 catalogue records