Chiari malformation

| Chiari malformation | |

|---|---|

| Synonym | Hindbrain herniation |

| |

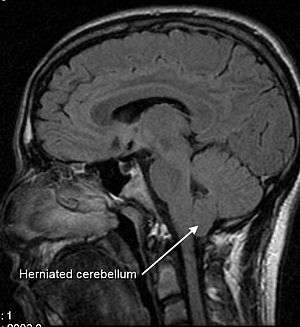

| A sagittal FLAIR MRI scan, from a patient with an Arnold-Chiari malformation, demonstrating tonsillar herniation of 7 mm. | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Neurosurgery |

| Complications | Syringomyelia |

| Types | I, II, III, IV [1] |

| Treatment | Decompressive surgery [2] |

| Frequency | 1 in 1000 |

A Chiari malformation (CM) is a structural defect in the cerebellum, characterised by a downward displacement of one or both cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum (the opening at the base of the skull). This can sometimes lead to non-communicating hydrocephalus[3] as a result of obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) outflow.[4] The cerebrospinal fluid outflow is caused by phase difference in outflow and influx of blood in the vasculature of the brain. The malformation is named for Austrian pathologist Hans Chiari. A type II CM is also known as an Arnold–Chiari malformation in honor of Chiari and German pathologist Julius Arnold.

CMs can cause headaches, difficulty swallowing (sometimes accompanied by gagging), choking and vomiting, dizziness, nausea, neck pain, unsteady gait (problems with balance), poor hand coordination (fine motor skills), numbness and tingling of the hands and feet, and speech problems (such as hoarseness).[5]

Less often, people with Chiari malformation may experience ringing or buzzing in the ears (tinnitus), weakness, slow heart rhythm, or fast heart rhythm, curvature of the spine (scoliosis) related to spinal cord impairment, abnormal breathing, such as central sleep apnea, characterized by periods of breathing cessation during sleep, and, in severe cases, paralysis.[5]

Signs and symptoms

- Headaches aggravated by Valsalva maneuvers, such as yawning, laughing, crying, coughing, sneezing or straining, bending over, or getting up suddenly[6]

- Tinnitus (ringing in the ears)

- Lhermitte's sign (electrical sensation that runs down the back and into the limbs)

- Vertigo (dizziness)

- Nausea

- Nystagmus (irregular eye movements; typically, so-called "downbeat nystagmus")

- Facial pain

- Muscle weakness

- Impaired gag reflex

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)[7]

- Restless leg syndrome

- Sleep apnea

- Sleep disorders[8]

- Impaired coordination

- Severe cases may develop all the symptoms and signs of a bulbar palsy

- Paralysis due to pressure at the cervico-medullary junction may progress in a so-called "clockwise" fashion, affecting the right arm, then the right leg, then the left leg, and finally the left arm; or the opposite way around.

- Papilledema on fundoscopic exam due to Increased intracranial pressure

- Pupillary dilation

- Dysautonomia: tachycardia (rapid heart), syncope (fainting), polydipsia (extreme thirst), chronic fatigue [9]

The blockage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow may also cause a syrinx to form, eventually leading to syringomyelia. Central cord symptoms such as hand weakness, dissociated sensory loss, and, in severe cases, paralysis may occur.[10]

Syringomyelia

Syringomyelia is a chronic progressive degenerative disorder characterized by a fluid-filled cyst located in the spinal cord. Its symptoms include pain, weakness, numbness, and stiffness in the back, shoulders, arms or legs. Other symptoms include headaches, the inability to feel changes in the temperature, sweating, sexual dysfunction, and loss of bowel and bladder control. It is usually seen in the cervical region but can extend into the medulla oblongata and pons or it can reach downward into the thoracic or lumbar segments. Syringomyelia is often associated with type I Chiari malformation and is commonly seen between the C-4 and C-6 levels. The exact development of syringomyelia is unknown but many theories suggest that the herniated tonsils in type I Chiari malformations cause a "plug" to form, which does not allow an outlet of CSF from the brain to the spinal canal. Syringomyelia is present in 25% of patients with type I Chiari malformations.[11]

Pathophysiology

The most widely accepted pathophysiological mechanism by which Chiari type I malformations occur is by a reduction or lack of development of the posterior fossa as a result of congenital or acquired disorders. Congenital causes include hydrocephalus, craniosynostosis (especially of the lambdoid suture), hyperostosis (such as craniometaphyseal dysplasia, osteopetrosis, erythroid hyperplasia), X-linked vitamin D-resistant rickets, and neurofibromatosis type I. Acquired disorders include space occupying lesions due to one of several potential causes ranging from brain tumors to hematomas.[12] Head trauma may cause cerebellar tonsillar ectopia, possibly because of dural strain. Additionally, ectopia may be present but asymptomatic until whiplash causes it to become symptomatic.[13] Posterior fossa hypoplasia causes reduced cerebral and spinal compliance.

Diagnosis

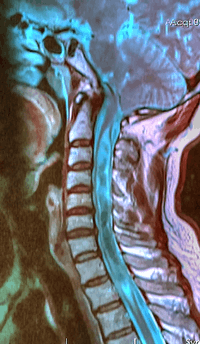

Diagnosis is made through a combination of patient history, neurological examination, and medical imaging.[14] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the best imaging modality for Chiari malformation since it visualizes neural tissue such as the cerebellar tonsils and spinal cord as well as bone and other soft tissues. CT and CT myelography are other options and were used prior to the advent of MRI, but they characterize syringomyelia and other neural abnormalities less well.

By convention the cerebellar tonsil position is measured relative to the basion-opisthion line, using sagittal T1 MRI images or sagittal CT images.[15] The selected cutoff distance for abnormal tonsil position is somewhat arbitrary since not everyone will be symptomatic at a certain amount of tonsil displacement, and the probability of symptoms and syrinx increases with greater displacement, however greater than 5 mm is the most frequently cited cutoff number, though some consider 3–5 mm to be "borderline," and symptoms and syrinx may occur above that.[15][16][17] One study showed little difference in cerebellar tonsil position between standard recumbent MRI and upright MRI for patients without a history of whiplash injury.[13] Neuroradiological investigation is used to first rule out any intracranial condition that could be responsible for tonsillar herniation. Neuroradiological diagnostics evaluate the severity of crowding of the neural structures within the posterior cranial fossa and their impact on the foramen magnum. Chiari 1.5 is a term used when both brainstem and tonsillar herniation through the foramen magnum are present.[18]

The diagnosis of a Chiari II malformation can be made prenatally through ultrasound.[19][20]

Classification

In the late 19th century, Austrian pathologist Hans Chiari described seemingly related anomalies of the hindbrain, the so-called Chiari malformations I, II and III. Later, other investigators added a fourth (Chiari IV) malformation. The scale of severity is rated I – IV, with IV being the most severe. Types III and IV are very rare.[21]

| Type | Presentation | Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|

| I |

Herniation of cerebellar tonsils .[1][22][23] Tonsillar ectopia below the foramen magnum, with greater than 5 mm below as the most commonly cited cutoff value for abnormal position (although this is considered somewhat controversial).[15][16][24][25] Syringomyelia of cervical or cervicothoracic spinal cord can be seen. Sometimes the medullary kink and brainstem elongation can be seen. Can be congenital, or acquired through trauma. When congenital, may be asymptomatic during childhood, but often manifests with headaches and cerebellar symptoms. Syndrome of occipitoatlantoaxial hypermobility is an acquired Chiari I malformation in patients with hereditary disorders of connective tissue.[26] Patients who exhibit extreme joint hypermobility and connective tissue weakness as a result of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or Marfan syndrome are susceptible to instabilities of the craniocervical junction; thus they are at risk for acquiring a Chiari malformation. |

Headache, neck pain, unsteady gait usually during childhood [1] |

| II | Also known as a Classic Chiari malformation. This is the only type also known as an Arnold-Chiari malformation. As opposed to the less pronounced tonsillar herniation seen with Chiari I, there is a larger cerebellar vermian displacement. Low lying torcular herophili (confluence of sinuses), tectal beaking, and hydrocephalus with consequent clival hypoplasia are classic anatomic associations.[27] Usually accompanied by a lumbar or lumbosacral myelomeningocele with tonsillar herniation below the foramen magnum.[1][28] The position of the torcular herophili is important for distinction from Dandy–Walker syndrome in which it is classically upturned. This is important because the hypoplastic cerebellum of Dandy–Walker may be difficult to distinguish from a Chiari malformation that has herniated or is ectopic on imaging. Colpocephaly may be seen due to the associated neural tube defect. | Paralysis below the spinal defect [1] |

| III | Associated with an occipital encephalocele containing a variety of abnormal neuroectodermal tissues. Syringomyelia and tethered cord as well as hydrocephalus is also seen.[1][29] | Abundant neurological deficits [1] |

| IV | Characterized by a lack of cerebellar development in which the cerebellum and brain stem lie within the posterior fossa with no relation to the foramen magnum. Associated with hypoplasia.[1][30] Equivalent to primary cerebellar agenesis.[31] | Not compatible with life [1] |

Other conditions sometimes associated with Chiari malformation include hydrocephalus,[32] syringomyelia, spinal curvature, tethered spinal cord syndrome, and connective tissue disorders[26] such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome[33] and Marfan syndrome.

Chiari malformation is the most frequently used term for this set of conditions. The use of the term Arnold–Chiari malformation has fallen somewhat out of favor over time, although it is used to refer to the type II malformation. Current sources use "Chiari malformation" to describe four specific types of the condition, reserving the term "Arnold-Chiari" for type II only.[34] Some sources still use "Arnold-Chiari" for all four types.[35]

Chiari malformation or Arnold–Chiari malformation should not be confused with Budd-Chiari syndrome,[36] a hepatic condition also named for Hans Chiari.

In Pseudo-Chiari Malformation, leaking of CSF may cause displacement of the cerebellar tonsils and similar symptoms sufficient to be mistaken for a Chiari I malformation.[37]

Treatment

While there is no current cure, the treatments for Chiari malformation are surgery and management of symptoms, based on the occurrence of clinical symptoms rather than the radiological findings. The presence of a syrinx is known to give specific signs and symptoms that vary from dysesthetic sensations to algothermal dissociation to spasticity and paresis. These are important indications that decompressive surgery is needed for patients with Chiari Malformation Type II. Type II patients have severe brain stem damage and rapidly diminishing neurological response.[38][39]

Decompressive surgery[2] involves removing the lamina of the first and sometimes the second or third cervical vertebrae and part of the occipital bone of the skull to relieve pressure. The flow of spinal fluid may be augmented by a shunt. Since this surgery usually involves the opening of the dura mater and the expansion of the space beneath, a dural graft is usually applied to cover the expanded posterior fossa.

A small number of neurological surgeons believe that detethering the spinal cord as an alternate approach relieves the compression of the brain against the skull opening (foramen magnum), obviating the need for decompression surgery and associated trauma. However, this approach is significantly less documented in the medical literature, with reports on only a handful of patients. It should be noted that the alternative spinal surgery is also not without risk.

Complications of decompression surgery can arise. They include bleeding, damage to structures in the brain and spinal canal, meningitis, CSF fistulas, occipito-cervical instability and pseudomeningeocele. Rare post-operative complications include hydrocephalus and brain stem compression by retroflexion of odontoid. Also, an extended CVD created by a wide opening and big duroplasty can cause a cerebellar "slump". This complication needs to be corrected by cranioplasty.[38]

In certain cases, irreducible compression of the brainstem occurs from in front (anteriorly or ventral) resulting in a smaller posterior fossa and associated Chiari malformation. In these cases, an anterior decompression is required. The most commonly used approach is to operate through the mouth (transoral) to remove the bone compressing the brainstem, typically the odontoid. This results in decompressing the brainstem and therefore gives more room for the cerebellum, thus decompressing the Chiari malformation. Arnold Menzes, MD, is the neurosurgeon who pioneered this approach in the 1970s at the University of Iowa. Between 1984 and 2008 (the MR imaging era), 298 patients with irreducible ventral compression of the brainstem and Chiari type 1 malformation underwent a transoral approach for ventral cervicomedullary decompression at the University of Iowa. The results have been excellent resulting in improved brainstem function and resolution of the Chiari malformation in the majority of patients.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of congenital Chiari I malformation, defined as tonsilar herniations of 3 to 5 mm or greater, was previously believed to be in the range of one per 1000 births, but is likely much higher.[26][40] Women are three times more likely than men to have a congenital Chiari malformation.[41] Type II malformations are more prevalent in people of Celtic descent.[40] A study using upright MRI found cerebellar tonsillar ectopia in 23% of adults with headache from motor-vehicle-accident head trauma. Upright MRI was more than twice as sensitive as standard MRI, likely because gravity affects cerebellar position.[13]

Cases of congenital Chiari malformation may be explained by evolutionary and genetic factors. Typically, an infant's brain weighs around 400g at birth and triples to 1100-1400g by age 11. At the same time the cranium triples in volume from 500 cm3 to 1500 cm3 to accommodate the growing brain.[42] During human evolution, the skull underwent numerous changes to accommodate the growing brain. The evolutionary changes included increased size and shape of the skull, decreased basal angle and basicranial length. These modifications resulted in significant reduction of the size of the posterior fossa in modern humans. In normal adults, the posterior fossa comprises 27% of the total intracranial space, while in adults with Chiari Type I, it is only 21%.[43] If a modern brain is paired with a less modern skull, the posterior fossa may be too small, so that the only place where the cerebellum can expand is the foramen magnum, leading to development of Chiari Type I.[44] H. neanderthalensis had platycephalic (flattened) skulls. Some cases of Chiari are associated with platybasia (flattening of the skull base).[45]

History

The history of Chiari malformation is described below and categorized by the year:

- 1883: Cleland was the first to describe Chiari II or Arnold–Chiari malformation on his report of a child with spina bifida, hydrocephalus, and anatomical alterations of the cerebellum and brainstem.[46]

- 1891: Hans Chiari, a Viennese pathologist, described the case of a 17-year-old woman with elongation of the tonsils into cone shaped projections which accompany the medulla and are crammed into the spinal canal.[46]

- 1907: Schwalbe and Gredig, pupils of German pathologist Julius Arnold, described four cases of meningomyelocele and alterations in the brainstem and cerebellum, and gave the name "Arnold-Chiari" to these malformations.[46][47]

- 1932: Van Houweninge Graftdijk was the first to report the surgical treatment of Chiari malformations. All patients died from surgery or postoperative complications.[46]

- 1935: Russell and Donald suggested that decompression of the spinal cord at the foramen magnum might facilitate the CSF circulation.[46]

- 1940: Gustafson and Oldberg diagnosed Chiari malformation with syringomyelia.[46]

- 1974: Bloch et al. described the tonsils position to be classified between 7 mm and 8 mm below cerebellum.[46]

- 1985: Aboulezz used MRI for discovery of extension[46]

Society and culture

The condition was brought to the mainstream on the series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation in the tenth-season episode "Internal Combustion" on February 4, 2010.[48] Chiari malformation was briefly mentioned on the medical drama House M.D. in the fifth season episode "House Divided"[49], and it was the focus of the sixth season episode "The Choice." It is also the focus of Private Practice Season 4 episode 4, where a pregnant woman is diagnosed with it. It was also mentioned in the medical drama A Gifted Man, in the first season episode "In Case of Separation Anxiety".[50] It is also featured in the 3rd and 4th episode of the 7th season of the serie Rizzoli & Isles where Dr. Maura Isles is diagnosed with the condition.[51][52][53]

Notable people

- Rosanne Cash[54] – U.S. singer-songwriter; daughter of Johnny Cash

- Julia Clukey[55] – U.S. luge competitor for Team USA in 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics

- Joanna David[56] – British television and stage actress

- J. B. Holmes – U.S. professional golfer

- Marissa Irwin[57] – U.S. fashion model with Chiari secondary to Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Bobby Jones[58] – U.S. World Golf Hall of Fame golfer and founder of the Augusta National Golf Club

- Leah Shapiro[59] – U.S. drummer for the band Black Rebel Motorcycle Club

- Michelle Stilwell – Canadian wheelchair racer and politician[60]

- Allysa Seely – Gold Medalist at the 2016 Summer Paralympics in the paratriathlon[61]

- Rachid Taha[62] – Algerian singer

Awareness

Chiari Malformation Awareness Month is September.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Vannemreddy, Prasad; Nourbakhsh, Ali; Willis, Brian; Guthikonda, Bharat (2010). "CongenitalChiari malformations: A review". Neurology India. 58 (1): 6–14. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.60387. PMID 20228456.

- 1 2 Guo, Fuyou; Wang, Meiyun; Long, Jiang; Wang, Huaili; Sun, Hongwei; Yang, Bo; Song, Laijun (2007). "Surgical Management of Chiari Malformation: Analysis of 128 Cases". Pediatric Neurosurgery. 43 (5): 375–81. doi:10.1159/000106386. PMID 17786002.

- ↑ Hydrocephalus at eMedicine

- ↑ Rosenbaum, RB; DP Ciaverella (2004). Neurology in Clinical Practice. Butterworth Heinemann. pp. 2192–2193. ISBN 0-7506-7469-5.

- 1 2 "Chiari malformation: Symptoms". Mayo Clinic. November 13, 2008. Archived from the original on February 11, 2010.

- ↑ Riveira, Carmiña; Pascual, Julio (2007). "Is Chiari type I malformation a reason for chronic daily headache?". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 11 (1): 53–5. doi:10.1007/s11916-007-0022-x. PMID 17214922.

- ↑ "Department of Neurological Surgery – University of Washington". Depts.washington.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-11-21. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/OnCall/story?id=6711810%5Bfull+citation+needed%5D

- ↑ "Dysautonomia News – Winter/Spring 2006". Dinet.org. Archived from the original on November 29, 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ Chiari Malformation at eMedicine

- ↑ Adnan BURINA; Dževdet SMAJLOVIĆ; Osman SINANOVIĆ; Mirjana VIDOVIĆ; Omer Ć. IBRAHIMAGIĆ (2009). "ARNOLD–CHIARI MALFORMATION AND SYRINGOMYELIA". Acta Med Sal. 38: 44–46. Archived from the original on 2012-09-18.

- ↑ Loukas M, Shayota BJ, Oelhafen K, Miller JH, Chern JJ, Tubbs RS, Oakes WJ (2011). "Associated disorders of Chiari Type I malformations: a review". Neurosurg Focus. 31 (3): E3. doi:10.3171/2011.6.FOCUS11112. PMID 21882908.

- 1 2 3 Freeman, Michael D.; Rosa, Scott; Harshfield, David; Smith, Francis; Bennett, Robert; Centeno, Christopher J.; Kornel, Ezriel; Nystrom, Ake; Heffez, Dan; Kohles, Sean S. (2010). "A case-control study of cerebellar tonsillar ectopia (Chiari) and head/neck trauma (whiplash)". Brain Injury. 24 (7–8): 988–94. doi:10.3109/02699052.2010.490512. PMID 20545453.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-03-05. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- 1 2 3 Barkovich, AJ; Wippold, FJ; Sherman, JL; Citrin, CM (1986). "Significance of cerebellar tonsillar position on MR". AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 7 (5): 795–9. PMID 3096099.

- 1 2 Aboulezz, AO; Sartor, K; Geyer, CA; Gado, MH (1985). "Position of cerebellar tonsils in the normal population and in patients with Chiari malformation: a quantitative approach with MR imaging". Journal of computer assisted tomography. 9 (6): 1033–6. doi:10.1097/00004728-198511000-00005. PMID 4056132.

- ↑ Chern, JJ; Gordon, AJ; Mortazavi, MM; Tubbs, RS; Oakes, WJ (July 2011). "Pediatric Chiari malformation Type 0: a 12-year institutional experience". Journal of Neurosurgery. Pediatrics. 8 (1): 1–5. doi:10.3171/2011.4.peds10528. PMID 21721881.

- ↑ Tubbs, RS; Iskandar, BJ; Bartolucci, AA; Oakes, WJ (November 2004). "A critical analysis of the Chiari 1.5 malformation". Journal of Neurosurgery. 101 (2 Suppl): 179–83. doi:10.3171/ped.2004.101.2.0179. PMID 15835105.

- ↑ Archived December 9, 2012, at Archive.is

- ↑ Cui, Li-Gang; Jiang, Ling; Zhang, Hua-Bin; Liu, Bin; Wang, Jin-Rui; Jia, Jian-Wen; Chen, Wen (2011). "Monitoring of cerebrospinal fluid flow by intraoperative ultrasound in patients with Chiari I malformation". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 113 (3): 173–6. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.10.011. PMID 21075511.

- ↑ "Arnold Chiari Malformation". Archived from the original on 2010-07-07.

- ↑ Kojima, Atsuhiro; Mayanagi, Keita; Okui, Shunichi (2009). "Progression of Pre-existing Chiari Type I Malformation Secondary to Cerebellar Hemorrhage". Neurologia Medico-chirurgica. 49 (2): 90–2. doi:10.2176/nmc.49.90. PMID 19246872.

- ↑ O'Shaughnessy, Brian A.; Bendok, Bernard R.; Parkinson, Richard J.; Shaibani, Ali; Walker, Matthew T.; Shakir, Ebrahim; Batjer, H. Hunt (2006). "Acquired Chiari malformation Type I associated with a supratentorial arteriovenous malformation". Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics. 104 (1 Suppl): 28–32. doi:10.3171/ped.2006.104.1.28. PMID 16509477.

- ↑ Smith, BW; Strahle, J; Bapuraj, JR; Muraszko, KM; Garton, HJ; Maher, CO (September 2013). "Distribution of cerebellar tonsil position: implications for understanding Chiari malformation". Journal of Neurosurgery. 119 (3): 812–9. doi:10.3171/2013.5.jns121825. PMID 23767890.

- ↑ Raffel, C (September 2013). "Cerebellar tonsil position and Chiari malformation". Journal of Neurosurgery. 119 (3): 810–1. doi:10.3171/2013.3.jns1339. PMID 23767894.

- 1 2 3 Milhorat, Thomas H.; Bolognese, Paolo A.; Nishikawa, Misao; McDonnell, Nazli B.; Francomano, Clair A. (2007). "Syndrome of occipitoatlantoaxial hypermobility, cranial settling, and Chiari malformation Type I in patients with hereditary disorders of connective tissue". Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 7 (6): 601–9. doi:10.3171/SPI-07/12/601. PMID 18074684.

- ↑ "Cleveland Clinic Children's Hospital Pediatric Radiology Image Gallery". Cleveland Clinic. 2010. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ↑ "Neuroradiology – Chiari malformation (I-IV)". Archived from the original on 2009-01-23.

- ↑ Arnold-Chiari+Malformation at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ↑ "Chiari Malformations – Department of Neurological Surgery". Archived from the original on 2008-05-16.

- ↑ Yu, Feng; Jiang, Qing-jun; Sun, Xi-yan; Zhang, Rong-wei (2015). "A new case of complete primary cerebellar agenesis: clinical and imaging findings in a living patient". Brain. 138 (Pt 6): e353. doi:10.1093/brain/awu239. PMC 4614135. PMID 25149410.

- ↑ "Neuropathology For Medical Students". Archived from the original on 2008-07-08.

- ↑ "Dr. Bland Discusses Chiari & EDS 4(10)". Conquerchiari.org. 2006-11-20. Archived from the original on 2013-06-25. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ "Chiari malformation". Dorlands Medical Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2009-09-01.

- ↑ Kaipo T. Pau. "Chapter XVIII.16. Developmental Brain Anomalies". In Jeffrey K. Okamoto; et al. Case Based Pediatrics For Medical Students and Residents. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28.

- ↑ "Code 453.0: Budd-Chiari Syndrome". 2008 ICD-9-CM Diagnosis. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05.

- ↑ "Spontaneous Spinal Cerebrospinal Fluid Leaks: Diagnosis". Archived from the original on 2011-12-11.

- 1 2 Alessia Imperato; Vincenzo Seneca; Valentina Cioffi; Giuseppe Colella; Michelangelo Gangemi (2011). "Treatment of Chiari malformation: who, when and how". Neurological Sciences. 32: 335–339. doi:10.1007/s10072-011-0709-y. Archived from the original on 2012-12-17.

- ↑ Klekamp, J.; Batzdorf, U.; Samii, M.; Bothe, H. W. (1996). "The surgical treatment of Chiari I malformation". Acta Neurochirurgica. 138 (7): 788–801. doi:10.1007/BF01411256. PMID 8869706.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-10-27. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-04. Retrieved 2012-12-28.

- ↑ Nolte J. The human brain: an introduction to its functional anatomy. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2002

- ↑ Furtado, Sunil V.; Reddy, Kalyan; Hegde, A.S. (2009). "Posterior fossa morphometry in symptomatic pediatric and adult Chiari I malformation". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 16 (11): 1449–54. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2009.04.005. PMID 19736012.

- ↑ Fernandes, Yvens Barbosa; Ramina, Ricardo; Campos-Herrera, Cynthia Resende; Borges, Guilherme (2013). "Evolutionary hypothesis for Chiari type I malformation". Medical Hypotheses. 81 (4): 715–9. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2013.07.035. PMID 23948602.

- ↑ Sgouros, Spyros; Kountouri, Melpomeni; Natarajan, Kal (2007). "Skull base growth in children with Chiari malformation Type I". Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics. 107 (3 Suppl): 188–92. doi:10.3171/PED-07/09/188. PMID 17918522.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Schijman, Edgardo (2004). "History, anatomic forms, and pathogenesis of Chiari I malformations". Child's Nervous System. 20 (5): 323–8. doi:10.1007/s00381-003-0878-y. PMID 14762679.

- ↑ Enersen, Daniel. "Julius Arnold". Whonamedit? A dictionary of medical eponyms. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ "clinic_duty: House MD – 5.22 House Divided". Community.livejournal.com. Archived from the original on 2010-02-12. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ Archived October 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ https://popcitylife.com/2016/06/14/rizzoli-isles-7x03-cops-vs-zombies-recap/

- ↑ https://twitter.com/RizzoliIslesWB/status/742526140837855233

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fm2GpTexDO4

- ↑ "Rosanne Cash recovering from brain surgery - Entertainment - Celebrities - TODAY.com". MSNBC. 2011-10-26. Archived from the original on 2009-09-01. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ Julia Clukey (21 January 2014). "Olympian: Brain disorder made me stronger". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "We all make fantastic blunders…". Telegraph. 2006-09-18. Archived from the original on 2015-04-03. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ↑ (no author given). "Marissa's story" (PDF). Great Neck, NY, U.S.A.: The Chiari Institute and MedNet Technologies, Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "Bobby Jones Society | Chiari & Syringomyelia Foundation". Csfinfo.org. Archived from the original on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ David Renshaw (18 October 2014). "Black Rebel Motorcycle Club cancel LA gig as drummer undergoes brain surgery". NME. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Gary Kingston (31 May 2008). "Lonely At The Top". The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ "Paratriathlete Allysa Seely on prosthetics and PRs". ESPN. July 5, 2016. Archived from the original on August 4, 2017.

- ↑ mjid, Safia (2018-09-14). "Mort à 59 ans, Rachid Taha souffrait d'une maladie génétique - H24info". H24info (in French). Retrieved 2018-09-22.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |