Archibald Spencer

| Archibald Spencer | |

|---|---|

| Born |

January 1, 1698 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died |

January 13, 1760 (aged 62) Annapolis, Maryland |

| Nationality | England |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Known for | Electricity |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

Archibald Spencer (January 1, 1698 – January 13, 1760) was a businessman, scientist, doctor, clergyman, and lecturer. He is noted for introducing the phenomenon of electricity to Benjamin Franklin.

Early life

Spencer was born on January 1, 1698, in Edinburgh, Scotland, with a given name of Adam which later changed to Archibald.[1] Some writers on Benjamin Franklin's life have stated that Spencer was a medical doctor,[2][3] and a male midwife[4][5] and specialized in diseases of the eye.[6] Historian Leo Lemay claims that there are no records that Spencer had any medical training in Edinburgh, but may have had medical training in France.[7]

Career

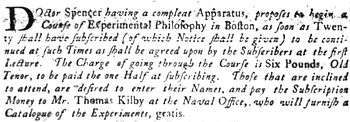

Spencer was a businessman in the British Colonies of America. From 1743 to 1751 he professionally conducted scientific lectures and demonstrations.[8] These were popularized in the colonies after Professor Isaac Greenwood started them in Boston in 1727. Spencer's first lecture advertisements are in the May 30 issues of the Boston Evening Post and the Boston Weekly Post-Boy. Spencer's charge for attending his course was expensive, £6, but was popular nevertheless. Spencer's science and mechanical lectures at first were on Isaac Newton's theory of light and state-of-the art techniques in medicine. Benjamin Franklin attended one of Spencer's dramatic lecture illustrations in Boston in 1743 and was not only amazed but amused.[1][6] He then acted as Spencer's agent when he came to Philadelphia in 1744 for his lectures, selling tickets and advertising them.[6][9][10] Advertisement were run in the Pennsylvania Gazette.[11]

The Leyden jar capacitor for high-voltage storage was invented in 1746 by Pieter van Musschenbroek, whom Franklin would meet later.[12] Then Spencer's Philadelphia lecture demonstrations on science included more electrical demonstrations and became elaborate with showmanship static electricity illustrations using the Leyden jar.[13][14] In 1746 Franklin bought all of Spencer's electrical equipment for his own personal use and experimentation.[15] Spencer introduced Franklin to the study of electricity through experimentation and was his mentor.[16][17][18] Franklin then trained three of his associates on Spencer's Philadelphia electrical illustrations, Samuel Domjen in 1748, Ebenezer Kinnersley in 1749, and Lewis Evans in 1751.[19]

Spencer lived in and helped form Anne Arundel County, Maryland. He made investments when he lived in the county. One such investment, with a group of other businessmen, was a supply of tobacco that was kept at Howard's Point Warehouse in the county. It totally burned up in an accidental fire in October 1758. Spencer petitioned the Province of Maryland government on November 29, 1758, that public funds be used to compensate the businessmen and himself for this loss. This request was turned down and no public funds were furnished.[20]

Societies

Spencer was a regular science speaker at the Philadelphia Tuesday Club and introduced the principles of electricity to the members, which included Franklin.[21] Spencer was admitted a member to Saint John's Grand Lodge of Boston in 1743 and attended at least two meetings when Franklin was a member.[22] Spencer joined the South River Club on July 10, 1755. He was active in the club for at least nine months. On September 4 and 18 he provided refreshments and food for the meetings. Spencer announced on January 22, 1756, to supply the club with copies of the Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper at a cost of 5 shillings a year.[20] He delivered the first of the newspapers two weeks later. After that his name does not again appear in the club's minutes. He was no longer an active member and records show from then on that he was a past member.[23]

Religion

Spencer practiced the Christian religion. He was trained by Kinnersley to become a Baptist minister and preached in Maryland starting in 1750.[21][24]

Death

Spencer died at the age of 62 in Annapolis, Maryland, on January 13, 1760.[25]

See also

References

- 1 2 Stearns 1970, p. 620.

- ↑ Rose 2004, p. 208.

- ↑ RUP 1999, p. 117.

- ↑ Meador 1975, p. 270.

- ↑ Brock 1982, p. 179.

- 1 2 3 Dray 2005, p. 38.

- ↑ LeMay 1964, p. 199.

- ↑ Stearns 1970, p. 507.

- ↑ Isaacson 2004, p. 134.

- ↑ LeMay 2009, p. 64.

- ↑ "A Great Number of Gentlemen". Pennsylvania Gazette. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 26, 1744 – via Newspapers.com

- ↑ Finger 2012, p. 82.

- ↑ Stearns 1970, pp. 506-507.

- ↑ Lemay 2013, p. 489.

- ↑ Miller 2009, p. 40.

- ↑ Ione 2016, p. 162.

- ↑ Wages 1979, p. 129.

- ↑ "Science and Medicine". Colonial America Reference Library. Encyclopedia.com. 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

Franklin's interest in electricity originated when he saw a traveling scientific lecturer, Archibald Spencer, perform an "electricity show" in Boston, Massachusetts.

- ↑ LeMay 2009, p. 78.

- 1 2 LeMay 1964, p. 214.

- 1 2 Breslaw 1988, p. xxii.

- ↑ LeMay 1964, p. 200.

- ↑ Warfield 1905, p. 202.

- ↑ Emerson 2016, p. 196.

- ↑ "ANNAPOLIS, January 17". The Maryland Gazette. Annapolis, Maryland. January 17, 1760 – via Newspapers.com

Sources

- Breslaw, Elaine G. (1988). Records of the Tuesday Club of Annapolis, 1745-56. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01334-8.

Spencer had been Benjamin Franklin's mentor in experiments with electricity.

- Brock, William Ranulf (January 1982). Scotus Americanus: A Survey of the Sources for Links Between Scotland and America in the Eighteenth Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-85224-420-3.

- Dray, Philip (2005). Stealing God's Thunder: Benjamin Franklin's Lightning Rod And the Invention of America. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-6810-1.

- Emerson, Roger L. (13 May 2016). Essays on David Hume, Medical Men and the Scottish Enlightenment: 'Industry, Knowledge and Humanity'. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-14164-8.

- Finger, Stanley (21 December 2012). Doctor Franklin's Medicine. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-0191-4.

- Ione, Amy (13 October 2016). Art and the Brain: Plasticity, Embodiment, and the Unclosed Circle. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-32299-8.

Dr. Archibald Spencer, an itinerant lecturer, initially acquainted Franklin with the mysterious powers of electricity in the summer of 1743.

- Isaacson, Walter (4 May 2004). Benjamin Franklin: An American Life. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5807-4.

- LeMay, J.A.L. (1964). Franklin's 'Dr. Spence':The reverend Archibald Spencer. Maryland Historical magazine. 59 (2 ed.). Baltimores, Maryland.

- LeMay, J. A. Leo (2009). The Life of Benjamin Franklin, Volume 3: Soldier, Scientist, and Politician, 1748–1757. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4121-1.

- Lemay, J. A. Leo (3 June 2013). The Life of Benjamin Franklin, Volume 2: Printer and Publisher, 1730-1747. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0929-7.

In the Autobiography, Franklin credited Spencer with awakening his interest in electricity.

- Meador, Roy (1975). Franklin, Revolutionary Scientist. Ann Arbor Science Publishers. ISBN 978-0-250-40121-5.

- Miller, Brandon Marie (1 October 2009). Benjamin Franklin, American Genius: His Life and Ideas with 21 Activities. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61374-130-6.

- Rose, F. Clifford (2004). Neurology of the Arts: Painting, Music, Literature. Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-86094-591-5.

- RUP (1999). Everyday Nature: Knowledge of the Natural World in Colonial New York. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4379-6.

- Stearns, Raymond Phineas (1970). Science in the British Colonies of America. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-00120-8.

- Wages, Jack D. (1979). Seventy-four writers of the colonial South. G. K. Hall. ISBN 978-0-8161-7979-4.

Spencer, who introduced Franklin to the study of electricity, was a 'prominent Marylander and his biography casts light on the religious, scientific, medical, social, and Masonic life in the colonies in the mid-eighteenth century.'

- Warfield, Joshua Dorsey (1905). The founders of Anne Arundel and Howard Counties, Maryland: A genealogical and biographical review from wills, deeds and church records. Kohn & Pollock.