Hebrew Gospel hypothesis

The Hebrew Gospel hypothesis (or proto-Gospel hypothesis or Aramaic Matthew hypothesis) is a group of theories based on the proposition that a lost gospel in Hebrew or Aramaic lies behind the four canonical gospels. It is based upon an early Christian tradition, deriving from the 2nd-century bishop Papias of Hierapolis, that the apostle Matthew composed such a gospel. Papias appeared to say that this Hebrew or Aramaic gospel was subsequently translated into the canonical gospel of Matthew, but modern studies have shown this to be untenable.[1] Modern variants of the hypothesis survive, but have not found favour with scholars as a whole.

Basis of the Hebrew gospel hypothesis: Papias and the early church fathers

The idea that some or all of the gospels were originally written in a language other than Greek begins with Papias of Hierapolis, c. 125–150 CE.[2] In a passage with several ambiguous phrases, he wrote: "Matthew collected the oracles (logia – sayings of or about Jesus) in the Hebrew language (Hebraïdi dialektōi — perhaps alternatively "Hebrew style") and each one interpreted (hērmēneusen — or "translated") them as best he could."[3] By "Hebrew" Papias would have meant Aramaic, the common language of the Middle East beside koine Greek [2] On the surface this implies that Matthew was originally written in Hebrew (Aramaic), but Matthew's Greek "reveals none of the telltale marks of a translation."[2] However, Blomberg states that "Jewish authors like Josephus, writing in Greek while at times translating Hebrew materials, often leave no linguistic clues to betray their Semitic sources."[4]

Scholars have put forward several theories to explain Papias: perhaps Matthew wrote two gospels, one, now lost, in Hebrew, the other the preserved Greek version; or perhaps the logia was a collection of sayings rather than the gospel; or by dialektōi Papias may have meant that Matthew wrote in the Jewish style rather than in the Hebrew language.[3] Nevertheless, on the basis of this and other information Jerome (c. 327–420) claimed that all the Jewish Christian communities shared a single gospel, identical with the Hebrew or Aramaic Matthew; he also claimed to have personally found this gospel in use among some communities in Syria.[1]

Jerome's testimony is regarded with skepticism by modern scholars. Jerome claims to have seen a gospel in Aramaic that contained all the quotations he assigns to it, but it can be demonstrated that some of them could never have existed in a Semitic language. His claim to have produced all the translations himself is also suspect, as many are found in earlier scholars such as Origen and Eusebius. Jerome appears to have assigned these quotations to the Gospel of the Hebrews, but it appears more likely that there were at least two and probably three ancient Jewish-Christian gospels, only one of them in a Semitic language.[1]

Quotes by Church Fathers

Matthew, who is also Levi, and who from a publican came to be an apostle, first of all composed a Gospel of Christ in Judaea in the Hebrew language and characters for the benefit of those of the circumcision who had believed. Who translated it after that in Greek is not sufficiently ascertained. Moreover, the Hebrew itself is preserved to this day in the library at Caesarea, which the martyr Pamphilus so diligently collected. I also was allowed by the Nazarenes who use this volume in the Syrian city of Beroea to copy it.

He (Shaul) being a Hebrew wrote in Hebrew, that is, his own tongue and most fluently; while things which were eloquently written in Hebrew were more eloquently turned into Greek.

— Jerome, 382 CE, On Illustrious Men, Book V

Matthew also issued a written gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect.

— Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3:1 [c.175-185 A.D.]

The first is written according to Matthew, the same that was once a tax collector, but afterwards an emissary of Yeshua the Messiah, who having published it for the Jewish believers, wrote it in Hebrew.

Composition of Matthew: modern consensus

The Gospel of Matthew is anonymous: the author is not named within the text and nowhere does he claim to have been an eyewitness to events. It probably originated in a Jewish-Christian community in Roman Syria towards the end of the first century AD,[6] and there is little doubt among modern scholars that it was composed in Koine Greek, the daily language of the time[7] [although this is disputed; see, for example, Carmignac, "Birth of the Synoptics", and Tresmontant, "The Hebrew Christ", both of whom postulate early Hebrew gospels.] The author, who is not named in the text itself but who was universally accepted by the early church to be the apostle Matthew, drew on three main sources, the Gospel of Mark, the alleged sayings collection known as the Q source, both in Greek, and material unique to his own community, called M.[8] Mark and Q were both written sources composed in Greek, but some of the parts of Q may have been translated from Aramaic into Greek more than once.[9] M is comparatively small, only 170 verses, made up almost exclusively of teachings; it probably was not a single source, and while some of it may have been written, most seems to have been oral.[10]

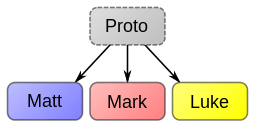

Modern forms of the hypothesis: the synoptic problem

The synoptic gospels are the three gospels of Mark, Matthew and Luke: they share much the same material in much the same order, and are clearly related. The precise nature of the relationship is the synoptic problem. The most widely held solution to the problem today is the two-source theory, which holds that Mark, plus another, hypothetical source, Q, were used by Matthew and Luke. But while this theory has widespread support, there is a notable minority view that Mark was written last using Matthew and Luke (the two-gospel hypothesis). Still other scholars accept Markan priority, but argue that Q never existed, and that Luke used Matthew as a source as well as Mark (the Farrer hypothesis).

A further, and very minority, theory is that there was a single gospel written in Hebrew or Aramaic. Today, this hypothesis is held to be discredited by most experts. As outlined subsequently, this was always a minority view, but in former times occasionally rather influential, and advanced by some eminent scholars:

Early modern period

Richard Simon of Normandy in 1689[11] asserted that an Aramaic or Hebrew Gospel of Matthew, lay behind the Nazarene Gospel, and was the Proto-Gospel. J. J. Griesbach[12] treated this as the first of three source theories as solutions to the synoptic problem, following (1) the traditional Augustinian utilization hypothesis, as (2) the original gospel hypothesis or proto-gospel hypothesis, (3) the fragment hypothesis (Koppe);[13] and (4) the oral gospel hypothesis or tradition hypothesis (Herder 1797).[14][15]

18th century: Lessing, Olshausen

A comprehensive basis for the original-gospel hypothesis was provided in 1804 by Johann Gottfried Eichhorn,[16] who argued for an Aramaic original gospel that each of the Synoptic evangelists had in a different form.[17]

Related is the "Aramaic Matthew hypothesis" of Theodor Zahn,[18] who shared a belief in an early lost Aramaic Matthew, but did not connect it to the surviving fragments of the Gospel of the Hebrews in the works of Jerome.[19][20]

18th Century scholarship was more critical. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1778) posited several lost Aramaic Gospels as Ur-Gospel or proto-Gospel common sources used freely for the three Greek Synoptic Gospels.[21] Johann Gottfried Eichhorn posited four intermediate Ur-Gospels, while Johann Gottfried von Herder argued for an oral Gospel tradition as an unwritten Urgospel, leading to Friedrich Schleiermacher's view of Logia as a Gospel source.[22][23]Reicke 2005, p. 52: ‘He asserted that an old Gospel of Matthew, presumed to have been written in Hebrew or rather in Aramaic and taken to lie behind the Nazarene Gospel, was the Proto-Gospel. In 1778 Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in Wolfenbuttel identified the...’[24] Hermann Olshausen (1832)[25] suggested a lost Hebrew Matthew was the common source of Greek Matthew and the Jewish-Christian Gospels mentioned by Epiphanius, Jerome and others.[26]Reicke 2005, p. 52: ‘No 2, the Proto-Gospel Hypothesis, stems from a remark of Papias implying that Matthew had compiled the Logia in Hebrew (Eusebius, History III. 39. 16). Following this, Epiphanius and Jerome held that there was an older Gospel of…’[27][28][29][30] Léon Vaganay (1940),[31] Lucien Cerfaux, Xavier Léon-Dufour and Antonio Gaboury (1952) attempted to revive Lessing's proto-gospel hypothesis.[32][33][34][35][36]

Nicholson, Handmann

Edward Nicholson (1879) proposed that Matthew wrote two Gospels, the first in Greek, the second in Hebrew. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (1915) in its article Gospel of the Hebrews noted that Nicholson cannot be said ...[to] have carried conviction to the minds of New Testament scholars."[37]

Rudolf Handmann (1888) proposed an Aramaic Gospel of the Hebrews[38] but reasoned that this was not the Hebrew Matthew and there never was a Hebrew Ur-Matthew.[39]

Edwards

James R. Edwards, in The Hebrew Gospel and the development of the synoptic tradition (2009), suggested that a lost Hebrew Ur-Matthew is the common source of both the Jewish-Christian Gospels and the unique L source material (material not sourced from Mark or Q) in the Gospel of Luke. A review of Edwards' book, including the reproduction of a diagram of Edwards' proposed relationship, was published by the Society of Biblical Literature's Review of Biblical Literature in March 2010.[40]

The Hebrew gospel hypothesis and modern criticism

Multiple Jewish-Christian Gospels

Carl August Credner (1832)[41] identified three Jewish-Christian Gospels: Jerome's Gospel of the Nazarenes, the Greek Gospel of the Ebionites cited by Epiphanius in his Panarion, and a Greek gospel cited by Origen, which he referred to as the Gospel of the Hebrews. In the 20th Century the majority school of critical scholarship, such as Hans Waitz, Philip Vielhauer and Albertus Klijn, proposed a tripartite distinction between Epiphanius' Greek Jewish Gospel, Jerome's Hebrew (or Aramaic) Gospel, and a Gospel of the Hebrews, which was produced by Jewish Christians in Egypt, and like the canonical Epistle to the Hebrews was Hebrew only in nationality not language. The exact identification of which Jewish Gospel is which in the references of Jerome, Origen and Epiphanius, and whether each church father had one or more Jewish Gospels in mind, is an ongoing subject of scholarly debate.[42] However the presence in patristic testimony concerning three different Jewish Gospels with three different traditions regarding the baptism of Christ suggests multiple traditions.[43]

19th century

Eichhorn's Ur-Gospel hypothesis (1794/1804) won little support in the following years.[44] General sources such as John Kitto's Cyclopedia describe the hypothesis[45] but note that it had been rejected by almost all succeeding critics.[46]

20th century

Acceptance of an original Gospel hypothesis in any form in the 20th century was minimal. Critical scholars had long moved on from the hypotheses of Eichhorn, Schleiermacher (1832) and K. Lachmann (1835).[47] Regarding the related question of the reliability of Jerome's testimony also saw few scholars taking his evidence at face value. Traditional Lutheran commentator Richard Lenski (1943) wrote regarding the "hypothesis of an original Hebrew Matthew" that "whatever Matthew wrote in Hebrew was so ephemeral that it disappeared completely at a date so early that even the earliest fathers never obtained sight of the writing".[48] Helmut Köster (2000) casts doubt upon the value of Jerome's evidence for linguistic reasons; "Jerome's claim that he himself saw a gospel in Aramaic that contained all the fragments that he assigned to it is not credible, nor is it believable that he translated the respective passages from Aramaic into Greek (and Latin), as he claims several times."[49] However, Lenski and Koster’s views are in sharp contrast with those of Schneemelcher. Schneemelcher cites several early fathers as seeing Hebrew Matthew including Clement of Alexandria (Stromata 2.9.45 and 5.14.96), Origen (in Joh. vol. II,12; in Jer. Vol. XV,4; in MT. vol. XV,p. 389 Benz-Kloostermann), Eusebius (Historia Ecclesiastica 3.25.5, 3.27.1-4, 3.39.17. 4.22.8 “Regarding Hegissipus (c. 180) and his memoirs Eusebius reports: He quotes from the Gospel according to the Hebrews and from the Syriac (Gospel) and in particular some words in the Hebrew tongue, showing that he was a convert from the Hebrews”, 3.24.6, 3.39.16, 5.8.2, 6.24.4, Theophania 4.12, 5.10.3), Jerome (Note by Schneemelcher “Jerome thus reluctantly confirms the existence of two Jewish Gospels, the Gospel according to the Hebrews and an Aramaic gospel. That the latter was at hand in the library in Caesareas is not to be disputed; it is at any rate likely on the ground of the citations of Eusebius in his Theophany. It will likewise be correct that the Nazaraeans used such an Aramaic gospel, since Epiphanius also testifies to this. That the Aramaic gospel, evidence of which is given by Hegesippus and Eusebius, is identical with the Gospel of the Nazaraeans, is not indeed absolutely certain, but perfectly possible, even very probable…).[50]

New evidence regarding the provenance of Matthew (as well as Mark and Luke) was presented by Jean Carmignac in The Birth of the Synoptics (Michael J. Wrenn, trans.; Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1987). Carmignac in 1963, during his work with the Dead Sea Scrolls, attempted to translate Mark from Greek to Hebrew for his use in a New Testament commentary based on the Dead Sea Scrolls. He expected many difficulties but unexpectedly discovered that the translation was not only easy, but seemed to point to Greek Mark as a translation from a Hebrew or Aramaic original.[51] Carmignac's discovery prompted further investigation, which yielded much evidence for a Hebrew origin for Mark and Matthew, and for a Lukan source. Among the nine types of Semitisms identified among the three Synoptics, Semitisms of Transmission are probably the strongest evidence for at least Mark and possibly Matthew as direct translations from a Hebrew original text. For example, "Mark 11:14 speaks of eating of the fruit = YWKL (according to the spelling of Qumran) and Matthew 21:19 to produce fruit YWBL: as the letters B and K resemble each other [in Qumran Hebrew] so greatly, the possibility for confusion is very likely."[52] Carmignac's little book contains dozens of such evidences. He had intended to produce a comprehensive volume but passed away before this work could be produced. Likewise, Claude Tresmontant hypothesized Hebrew originals for all four Gospels in The Hebrew Christ.

References.

- 1 2 3 Köster 2000, p. 207.

- 1 2 3 Bromiley 1979, p. 571.

- 1 2 Turner 2008, p. 15–16.

- ↑ Blomberg 1992, p. 40.

- ↑ Translation from the Latin text edited by E. C. Richardson and published in the series "Texte und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der altchristlichen Literatur,". 14. Leipzig. 1896. pp. 8, 9.

- ↑ Duling 2010, p. 298, 302.

- ↑ Aland & Aland 1995, p. 52.

- ↑ Burkett 2002, p. 175–6.

- ↑ Koester 1990, p. 317.

- ↑ Van Voorst 2000, p. 137–9, 143–8.

- ↑ Histoire critique du texte du Nouveau Testament, Rotterdam 1689.

- ↑ Commentatio qua Marci evangelium totum e Matthaei et Lucae commentariis decerptum esse monstratur, Ienae 1794,

- ↑ Marcus non epitomator Matthaei, Programme Universität Gottingen (Helmstadii, 1792); reprinted in D. J. Pott and G. A. Ruperti (eds.), Sylloge commentationum theologicarum, vol. I (Helmstadii, 1800), pp. 35-69.

- ↑ Von Gottes Sohn, der Welt Heiland, nach Johannes Evangelium. Nebst einer Regel der Zusammenstimmung unserer Evangelien aus ihrer Entstehung und Ordnung, Riga, 1797.

- ↑ Reicke, Bo (1965), Monograph series, 34, Society for New Testament Studies, pp. 51–2,

...whereas the last one was made public only after the final version of his Commentatio had appeared. The three source-theories referred to are these: (2) the Proto-Gospel Hypothesis; (3) the Fragment Hypothesis; (4) the Tradition Hypothesis. …Richard Simon... He asserted that an old Gospel of Matthew, presumed to have been written in Hebrew or rather in Aramaic and taken to lie behind the Nazarene Gospel, was the Proto-Gospel.

- ↑ Einleitung in das neue Testament, Leipzig, Weidmann 1804.

- ↑ Schnelle, Udo (1998), The history and theology of the New Testament writings, p. 163 .

- ↑ Einleitung in das Neue Testament, Leipzig 1897.

- ↑ A. T. Robertson (1911), Commentary on the Gospel According to Matthew,

What is its relation to the Aramaic Matthew? This is the crux of the whole matter. Only a summary can be attempted. (a) One view is that the Greek Matthew is in reality a translation of the Aramaic Matthew. The great weight of Zahn's...

- ↑ Homiletic review, 1918,

The chief opponent is Zahn, who holds that the Aramaic Matthew comes first. Zahn argues from Irenseus and Clement of Alexandria that the order of the gospels is the Hebrew (Aramaic) Matthew, Mark, Luke…

- ↑ "Neue Hypothese über die Evangelisten als blos menschliche Geschichtsschreiber betrachtet", in Karl Gotthelf Lessing (ed.), Gotthold Ephraim Lessings Theologischer Nachlass, Christian Friedrich Voß und Sohn, Berlin 1784, pp 45-73.

- ↑ Mariña, Jacqueline (2005), The Cambridge Companion to Friedrich Schleiermacher, p. 234,

Lessing argued for several versions of an Aramaic Urgospel, which were later translated into Greek as the... Eichhorn built on Lessing's Urgospel theory by positing four intermediate documents explaining the complex relations among the... For Herder, the Urgospel, like the Homeric...

- ↑ Neue Hypothese über die Evangelisten als bloss menschliche Geschichtsschreiber [New hypothesis on the Evangelists as merely human historians], 1778 .

- ↑ Nellen, Rabbie & 1994 1994, p. 73: ‘I am referring here to the Proto-Gospel Hypothesis of Lessing and the Two Gospel Hypothesis of Griesbach. These theories tried to explain the form of the Gospels by assuming that they are...

- ↑ Nachweis

- ↑ Edwards (2009), The Hebrew Gospel and the development of the synoptic tradition, p. xxvii .

- ↑ Neusner, Jacob; Smith, Morton (1975), Christianity, Judaism and other Greco-Roman cults: Studies for..., p. 42,

...developed out of this latter form of the proto-gospel hypothesis: namely Matthew and Luke have copied an extensive proto-gospel (much longer than Mark since it included such material as the sermon on the mount, etc.

- ↑ Bellinzoni, Arthur J; Tyson, Joseph B; Walker, William O (1985), The Two-source hypothesis: a critical appraisal,

Our present two-gospel hypothesis developed out of this latter form of the proto-gospel hypothesis: namely Matthew and Luke have copied an extensive proto-gospel (much longer than Mark since it included such material as the sermon on...

- ↑ Powers 2010, p. 22‘B. Reicke comments (Orchard and Longstaff 1978, 52): [T]he Proto-Gospel Hypothesis... stems from a remark of Papias implying that Matthew had compiled the logia in Hebrew (Eusebius, History 3.39.16). Following this, Epiphanius and...’

- ↑ Nellen & Rabbie 1994, p. 73: ‘I am referring here to the Proto-Gospel Hypothesis of Lessing and the Two Gospel Hypothesis of Griesbach. ... 19 (on Lessing's Proto-Gospel Hypothesis, "Urevangeli- umshypothese") and 21-22 (on Griesbach's Two Gospel Hypothesis).’

- ↑ Vaganay, Léon (1940), Le plan de l'Épître aux Hébreux (in French) .

- ↑ Hayes, John Haralson (2004), "The proto-gospel hypothesis", New Testament, history of interpretation,

The University of Louvain was once a center of attempts to revive Lessing's proto-gospel theory, beginning in 1952 with lectures by Leon Vaganay and Lucien Cerfaux 8, who started again from Papias's reference to a...

- ↑ Reicke, Bo (1986), The roots of the synoptic gospels

- ↑ Hurth, Elisabeth (2007), Between faith and unbelief: American transcendentalists and the…, p. 23,

Ralph Waldo Emerson was even prepared to go beyond Johann Gottfried Eichhorn's Proto-Gospel hypothesis, arguing that the common source for the synoptic Gospels was the oral tradition. The main exposition of this view was, as Emerson pointed out in his fourth vestry...

- ↑ Interpretation, Union Theological Seminary in Virginia, 1972,

Gaboury then goes on to examine the other main avenue of approach, the proto-Gospel hypothesis. Reviewing the work of Pierson Parker, Leon Vaganay, and Xavier Leon-Dufour (who is Antonio Gaboury's mentor), the writer claims that they have not...

- ↑ Hurth, Elisabeth (1989), In His name: comparative studies in the quest for the historical…,

Emerson was even prepared to go beyond Eichhorn's Proto-Gospel hypothesis and argued that the common source for the synoptic Gospels was the oral tradition. The main exposition of this view was, as Emerson pointed out in his fourth...

- ↑ Orr, James, ed. (1915), "Gospel of the Hebrews", International Standard Bible Encyclopedia .

- ↑ Handmann, R (1888), "Das Hebräer-Evangelium" [The Hebrew Gospel], Texte und Untersuchungen (in German), Leipzig, 3: 48

- ↑ Schaff, Philip (1904), A select library of Nicene and post-Nicene fathers,

Handmann makes the Gospel according to the Hebrews a second independent source of the Synoptic Gospels, alongside of the "Ur-Marcus" (a theory which, if accepted, would go far to establish its identity with the Hebrew Matthew)

. - ↑ Friedrichsen, Timothy A (March 2010), "Review" (PDF), RBL .

- ↑ Beitrage zur Einleitung in die biblischen Schriften (in German), Halle, 1832 .

- ↑ Vielhauer, cf. Craig A. Evans, cf. Klauck

- ↑ Vielhauer, Philip, "Introductory section to Jewish Christian Gospels", Schneemelcher NTA, 1 .

- ↑ Powers 2010, p. 481: ‘Others have taken up this basic concept of an Ur-Gospel and explained the idea further. In particular JG Eichhorn advanced (1794/1804) a very complicated version of the primal Gospel hypothesis that won little support, and then K Lachmann developed (1835) the thesis that all three Synoptics are dependent on a common source...’

- ↑ Kitto, John (1865), A Cyclopedia of Biblical literature, p. 158,

We are thus brought to consider Eichhorn's famous hypothesis of a so-called original Gospel, now lost. A brief written narrative of the life of Christ is supposed to have been in existence, and to have had additions made to it at different periods. Various copies of this original Gospel, with these additions, being extant in the time of the evangelists, each of the evangelists is supposed to have used a different copy as the basis of his Gospel. In the hands of Bishop Marsh, who adopted and modified the hypothesis of Eichhorn, this original Gospel becomes a very complex thing. He supposed that there was a Greek translation of the Aramaean original Gospel, and various transcripts...

- ↑ Davidsohn, Samuel (1848), An Introduction to the New Testament, 3, p. 391,

Perhaps Eichhorn's hypothesis weakens the authenticity. It has been rejected, however, by almost all succeeding critics.

- ↑ Farmer, William Reuben, The Synoptic Problem a Critical Analysis, pp. 13–6 .

- ↑ Lenski, Richard CH (2008) [1943], "The Hypothesis of an Original Hebrew", The Interpretation of St. Matthew's Gospel 1–14, pp. 12–14,

Various forms of this hypothesis have been offered...

- ↑ Introduction to the New Testament, 2, p. 207,

This hypothesis has survived into the modern period; but several critical studies have shown that it is untenable. First of all, the Gospel of Matthew is not a translation from Aramaic but was written in Greek on the basis of two Greek documents (Mark and the Sayings Gospel Q). Moreover, Jerome's claim that he himself saw a gospel in Aramaic that contained all the fragments that he assigned to it is not credible, nor is it believable that he translated the respective passages from Aramaic into Greek (and Latin), as he claims several times. ...It can be demonstrated that some of these quotations could never have existed in a Semitic language.

- ↑ Wilhelm Schneelmelcher, New Testament Apocrypha, volume 1, 1991 p. 134-178

- ↑ Carmignac, Jean (1987). The Birth of the Synoptics. Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780819908872.

- ↑ ibid.,. p. 32.

Bibliography

- Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995), The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, Wm B Eerdmans .

- Blomberg, Craig A, ed. (1992), Matthew, Broadman .

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W, ed. (1979), International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A–D, Wm B Eerdmans .

- Burkett, Delbert (2002), An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7 .

- Cameron, Ron (1982), The Other Gospels: Non-Canonical Gospel Texts, Westminster John Knox .

- Duling, Dennis C (2010), "The Gospel of Matthew", in Aune, David E, Blackwell companion to the New Testament, Wiley-Blackwell .

- Ehrman, Bart D (2003), Lost Scriptures, OUP .

- ———; Plese, Zlatko (2011), The Apocryphal Gospels: Texts and Translations, OUP

- Harrington, Daniel J. (1991), The Gospel of Matthew, Liturgical Press .

- Koester, Helmut (1990). Ancient Christian Gospels: Their History and Development. Trinity Press. ISBN 978-0-334-02459-0.

- Köster, Helmut (2000) [1982], Introduction to the New Testament: History and Literature of Early Christianity (2 ed.), Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-014692-9 .

- Lapham, Fred (2003). An Introduction to the New Testament Apocrypha. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-6979-3.

- Nellen, Henk JM; Rabbie, Edwin (1994), Hugo Grotius, Theologian: Essays in Honour of Guillaume Henri Marie Posthumus Meyjes, Brill .

- Powers, B Ward (2010), The Progressive Publication of Matthew, B&H Publishing Group .

- Reicke, Bo (2005), "Griesbach's Answer to the Synoptic Question", in Orchard, Bernard; Longstaff, Thomas RW, J. J. Griesbach: Synoptic and Text – Critical Studies 1776–1976 .

- Turner, David L (2008), Matthew, Baker .

- Van Voorst, Robert E (2000), Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence, Wm B Eerdmans

- Witherington, Ben (2001), The Gospel of Mark: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary, Wm B Eerdmans .