Antares

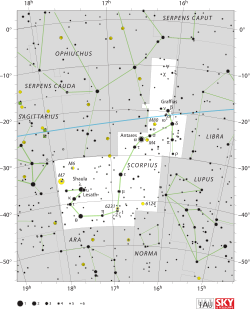

Antares (/ænˈtɑːriːz/), also designated Alpha Scorpii (α Scorpii, abbreviated Alpha Sco, α Sco), is on average the fifteenth-brightest star in the night sky, and the brightest star in the constellation of Scorpius. Distinctly reddish when viewed with the naked eye, Antares is a slow irregular variable star that ranges in brightness from apparent magnitude +0.6 to +1.6. Often referred to as "the heart of the scorpion", Antares is flanked by Sigma and Tau Scorpii in the center of the constellation.

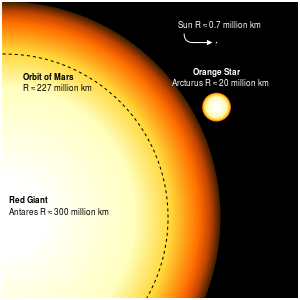

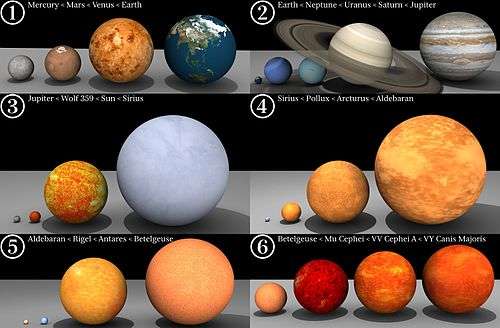

Classified as a red supergiant of spectral type M1.5Iab-Ib, Antares is the brightest, most massive, and most evolved stellar member of the nearest OB association (the Scorpius–Centaurus Association). Antares is a member of the Upper Scorpius subgroup of the Scorpius–Centaurus Association, which contains thousands of stars with mean age 11 million years at a distance of approximately 170 parsecs (550 ly). Its exact size remains uncertain, but if placed at the center of the solar system it would reach to somewhere between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. The mass is calculated to be around 12 times that of the Sun.

Nomenclature

α Scorpii (Latinised to Alpha Scorpii) is the star's Bayer designation. It also has the Flamsteed designation 21 Scorpii, as well as catalogue designations such as HR 6134 in the Bright Star Catalogue and HD 148478 in the Henry Draper Catalogue. As a prominent infrared source, it appears in the Two Micron All-Sky Survey catalogue as 2MASS J16292443-2625549 and the Two Micron All-Sky Survey catalogue as IRAS 16262-2619. It is also catalogued as a double star WDS J16294-2626 and CCDM J16294-2626.

Its traditional name Antares derives from the Ancient Greek Ἀντάρης,[15] meaning "rival to-Ares" ("opponent to-Mars"), due to the similarity of its reddish hue to the appearance of the planet Mars.[16] The comparison of Antares with Mars may have originated with early Mesopotamian astronomers.[17] However, some scholars have speculated that the star may have been named after Antar, or Antarah ibn Shaddad, the Arab warrior-hero celebrated in the pre-Islamic poems Mu'allaqat.[17] In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organised a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[18] to catalog and standardise proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016[19] included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN; which included Antares for this star. It is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[20]

Observational history

Antares and its red color have been known since antiquity.

Antares is a variable star and is listed in the General Catalogue of Variable Stars but as a Bayer-designated star it does not have a separate variable star designation.[21] Research published in 2017 demonstrated that Aboriginal people from South Australia observed the variability of Antares and incorporated it into their oral traditions as Waiyungari.[22]

Properties

Antares A is a red supergiant star with a stellar classification of M1.5Iab-Ib, and is indicated to be a spectral standard for that class.[4] Due to the nature of star, the derived parallax measurements have large errors, so that the true distance of Antares is approximately 550 light-years (170 parsecs) from the Sun.[1]

Luminosity and mass

The brightness of Antares at visual wavelengths is about 10,000 times that of the Sun, but because the star radiates a considerable part of its energy in the infrared part of the spectrum, the true bolometric luminosity is around 100,000 times that of the Sun. There is a large margin of error assigned to values for the bolometric luminosity, typically 30% or more. There is also considerable variation between values published by different authors, for example 75,900 L☉ and 97,700 L☉ published in 2012 and 2013.[11][9]

The mass of the star has been calculated to be approximately 12 M☉,[11] or 11 to 14.3 M☉.[9] Comparison of the effective temperature and luminosity of Antares to theoretical evolutionary tracks for massive stars suggest a progenitor mass of 17 M☉ and an age of 12 million years (MYr),[11] or an initial mass of 15 M☉ and an age of 11 to 15 MYr.[9] Massive stars like Antares are expected to become supernovae.[23]

Size

Like most cool supergiants, Antares size has much uncertainty due to the tenuous and translucent nature of the extended outer regions of the star. Defining an effective temperature is difficult due to spectral lines being generated at different depths within the atmosphere, and linear measurements produce different results depending on the wavelength observed.[24] In addition, Antares appears to pulsate, varying its radius by 165 R☉ or 19%.[11] It also varies in temperature by 150 K, lagging 70 days behind radial velocity changes which are likely to be caused by the pulsations.[12]

The diameter of Antares can be measured most accurately using interferometry or observing lunar occultations events. An apparent diameter from occultations 41.3 ± 0.1 milliarcseconds has been published.[25] Interferometry allows synthesis of a view of the stellar disc, which is then represented as a limb-darkened disk surrounded by an extended atmosphere. The diameter of the limb-darkened disk was measured as 37.38±0.06 milliarcseconds in 2009 and 37.31±0.09 milliarcseconds in 2010. The linear radius of the star can be calculated from its angular diameter and distance. However, the distance to Antares is not known with the same accuracy as modern measurements of its diameter. Using the Hipparcos satellite's trigonometric parallax of 5.40″±1.68″[26]) leads to a radius of about 680 R☉.[9] Older radii estimates exceeding 850 R☉ were derived from older measurements of the diameter,[12] but those measurements are likely to have been affected by asymmetry of the atmosphere and the narrow range of infrared wavelengths observed; Antares has an extended shell which radiates strongly at those particular wavelengths.[9] Despite its large size compared to the Sun, Antares is dwarfed by even larger red supergiants, such as VY Canis Majoris, which is almost 30 times larger in terms of volume, or VV Cephei A and Mu Cephei.

Variable star

Antares is a type LC slow irregular variable star, whose apparent magnitude slowly varies between extremes of +0.6 and +1.6, although usually near magnitude +1.0. There is no obvious periodicity, but statistical analyses have suggested periods of 1,733 days or 1650±640 days.[2] No separate long secondary period has been detected,[27] although it has been suggested that primary periods longer than a thousand days are analogous to long secondary periods.[2]

Position

Antares is visible in the sky all night around May 31 of each year, when the star is at opposition to the Sun. At this time, Antares rises at dusk and sets at dawn as seen at the equator. For approximately two to three weeks on either side of November 30, Antares is not visible in the night sky, because it is near conjunction with the Sun;[28] this period of invisibility is longer in the Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern Hemisphere, since the star's declination is significantly south of the celestial equator.

Antares is 4.57 degrees south of the ecliptic, one of four first magnitude stars within 6.5° of the ecliptic (the others are Spica, Regulus and Aldebaran) and so can be occulted by the Moon. On 31 July 2009, Antares was occulted by the Moon. The event was visible in much of southern Asia and the Middle East.[29][30] Every year around December 2 the Sun passes 5° north of Antares.[28]

Companion star

Antares has a magnitude 5.5 companion star, Antares B, that changed from an angular separation (from its primary, Antares A) of 3.3 arcseconds in 1854 to 2.67" +/-0.01" in 2006.[32] It was first observed by Scottish astronomer James William Grant FRSE while in India on 23 July 1844.[33] The last is equal to a projected separation of about 529 astronomical units (au) at the estimated distance of Antares, giving a minimum value for the separation of the pair. Spectroscopic examination of the energy states in the outflow of matter from the companion star suggests that it is about 224 au beyond the primary.[5] Antares B is a blue-white main-sequence star of spectral type B2.5V; it also has numerous unusual spectral lines suggesting it has been polluted by matter ejected by Antares A.[5]

The companion star is normally difficult to see in small telescopes due to glare from Antares A, but can sometimes be seen in apertures over 150 millimetres (5.9 inches).[34] The companion is often described as green, but this is probably either a contrast effect,[35] or the result of the mixing of light from the two stars when they are seen together through a telescope and are too close to be completely resolved. Antares B can sometimes be observed with a small telescope for a few seconds during lunar occultations while Antares A is hidden by the Moon. It was discovered by Johann Tobias Bürg during one such occultation on April 13, 1819,[36] but until its existence was confirmed in 1846 it was thought by some to be merely the light of Antares viewed through the Moon's atmosphere (which at the time was theorised to exist).[37] When observed by itself during such an occultation, the companion appears a profound blue or bluish-green color.[37]

The orbit of the companion star is poorly known, as attempts to analyse the radial velocity of Antares need to be unravelled from the star's own pulsations.[12] Orbital periods are possible within a range of 1,200[38] to 2,562 years.[39]

Occultations by Moon and Planets

Lunar occultations of Antares are fairly common, depending on the Saros cycle The last cycle ended in 2010 and the next begins in 2023. Shown at right is a video of a reappearance event, clearly showing events for both components.

Antares can also be occulted by the planets, e.g. Venus (called a planetary occultation), but these events are extremely rare. The last occultation of Antares by Venus took place on September 17, 525 BC; the next one will take place on November 17, 2400. Other planets have been calculated not to have occulted Antares over the last millennium, and nor will this occur during the next millennium, as the planets following the ecliptic always pass northward of Antares due to the actual planetary node positions and inclinations.

Supernova progenitor

1. Mercury < Mars < Venus < Earth

2. Earth < Neptune < Uranus < Saturn < Jupiter

3. Jupiter < Wolf 359 < Sun < Sirius

4. Sirius < Pollux < Arcturus < Aldebaran

5. Aldebaran < Rigel < Antares < Betelgeuse

6. Betelgeuse < Mu Cephei < VV Cephei A < VY Canis Majoris.

Antares, like the similarly-sized red giant Betelgeuse in the constellation Orion, will almost certainly explode as a supernova,[40] probably within the next ten thousand years. For a few months, the Antares supernova could be as bright as the full moon and be visible in daytime.[23]

Other names

In the Babylonian star catalogues dating from at least 1100 BCE, Antares was called GABA GIR.TAB, "the Breast of the Scorpion". In MUL.APIN, which dates between 1100 and 700 BC, it is one of the stars of Ea in the southern sky and marks breast of the Scorpion goddess Ishhara.[41] Later names that translate as "the Heart of Scorpion" include Calbalakrab from the Arabic Qalb al-Άqrab.[42] This had been directly translated from the Ancient Greek Καρδία Σκορπίου Kardia Skorpiū. Cor Scorpii translated above Greek name into Latin.[17]

In ancient Mesopotamia, Antares may have been known by the following names: Urbat, Bilu-sha-ziri ("the Lord of the Seed"), Kak-shisa ("the Creator of Prosperity"), Dar Lugal ("The King"), Masu Sar ("the Hero and the King"), and Kakkab Bir ("the Vermilion Star").[17] In ancient Egypt, Antares represented the scorpion goddess Serket (and was the symbol of Isis in the pyramidal ceremonies).[17]

In Persia, Antares was known as Satevis, one of the four "royal stars".[43] In India, it with Sigma and Tau Scorpii were Jyeshthā (the eldest or biggest, probably attributing its huge size), one of the nakshatra (Hindu lunar mansions).[17] The ancient Chinese called Antares (Chinese: 心宿二; pinyin: Xīnxiù'èr; literally: "second star of mansion Heart"), because it was the second star of the mansion Xin (心). It was the national star of the Shang Dynasty, and it was sometimes referred to as (Chinese: 火星; pinyin: Huǒxīng; literally: "fiery star") because of its reddish appearance.

The Māori people of New Zealand call Antares Rehua, and regard it as the chief of all the stars. Rehua is father of Puanga/Puaka (Rigel), an important star in the calculation of the Māori calendar. The Wotjobaluk Koori people of Victoria, Australia, knew Antares as Djuit, son of Marpean-kurrk (Arcturus); the stars on each side represented his wives. The Kulin Kooris saw Antares (Balayang) as the brother of Bunjil (Altair).[44]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357.

- 1 2 3 4 Kiss, L. L.; Szabo, G. M.; Bedding, T. R. (2006). "Variability in red supergiant stars: pulsations, long secondary periods and convection noise". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 372 (4): 1721–1734. arXiv:astro-ph/0608438. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.372.1721K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10973.x. ISSN 0035-8711.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoffleit, D.; Warren, W. H. (1995). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Bright Star Catalogue, 5th Revised Ed. (Hoffleit+, 1991)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: V/50. Originally published in: 1964BS....C......0H. 5050. Bibcode:1995yCat.5050....0H. Vizier database entry CDS. Accessed on line September 07, 2012

- 1 2 Keenan, Philip C; McNeil, Raymond C (1989). "The Perkins catalog of revised MK types for the cooler stars". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 71: 245. Bibcode:1989ApJS...71..245K. doi:10.1086/191373.

- 1 2 3 Baade, R.; Reimers, D. (October 2007). "Multi-component absorption lines in the HST spectra of α Scorpii B". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (1): 229–237. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..229B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077308.

- ↑ Evans, D. S. (June 20–24, 1966). "The Revision of the General Catalogue of Radial Velocities". In Batten, Alan Henry; Heard, John Frederick. Determination of Radial Velocities and their Applications, Proceedings from IAU Symposium no. 30. Determination of Radial Velocities and their Applications. 30. University of Toronto: International Astronomical Union. p. 57. Bibcode:1967IAUS...30...57E.

- ↑ Buick, Tony (2010). "Classification of the Stars". The Rainbow Sky. Patrick Moore's Practical Astronomy Series. pp. 43–71. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1053-0_4. ISBN 978-1-4419-1052-3. ISSN 1431-9756.

- 1 2 Schröder, K.-P.; Cuntz, M. (April 2007), "A critical test of empirical mass loss formulas applied to individual giants and supergiants", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 465 (2): 593–601, arXiv:astro-ph/0702172, Bibcode:2007A&A...465..593S, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066633

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ohnaka, K; Hofmann, K.-H; Schertl, D; Weigelt, G; Baffa, C; Chelli, A; Petrov, R; Robbe-Dubois, S (2013). "High spectral resolution imaging of the dynamical atmosphere of the red supergiant Antares in the CO first overtone lines with VLTI/AMBER". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 555: A24. arXiv:1304.4800. Bibcode:2013A&A...555A..24O. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321063.

- ↑ https://www.aavso.org/vsots_alphasco

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mark J. Pecaut; Eric E. Mamajek & Eric J. Bubar (February 2012). "A Revised Age for Upper Scorpius and the Star Formation History among the F-type Members of the Scorpius-Centaurus OB Association". Astrophysical Journal. 746 (2): 154. arXiv:1112.1695. Bibcode:2012ApJ...746..154P. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/746/2/154.

- 1 2 3 4 Pugh, T.; Gray, D.F. (2013). "On the Six-year Period in the Radial Velocity of Antares A". The Astronomical Journal. 145 (2): 4. Bibcode:2013AJ....145...38P. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/145/2/38. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 Kudritzki, R. P.; Reimers, D. (1978). "On the absolute scale of mass-loss in red giants. II. Circumstellar absorption lines in the spectrum of alpha Sco B and mass-loss of alpha Sco A". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 70: 227. Bibcode:1978A&A....70..227K.

- ↑ Allen, Richard Hinckley (1899). Star-names and their meanings. G. E. Stechert. pp. 364–367. Retrieved 2011-12-31.

- ↑ ἀντάρης. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Fred Gettings (1990). The Arkana Dictionary of Astrology. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-14-019287-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Allen, R.H. (1963). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning (Reprint ed.). New York, NY: Dover Publications Inc. pp. 364–366. ISBN 0-486-21079-0.

- ↑ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2009). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2007-2013)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/gcvs. Originally published in: 2009yCat....102025S. 1. Bibcode:2009yCat....102025S.

- ↑ Hamacher, D.W. "Observations of red–giant variable stars by Aboriginal Australians". The Australian Journal of Anthropology. arXiv:1709.04634. Bibcode:2018AuJAn..29...89H. doi:10.1111/taja.12257.

- 1 2 Hockey, T.; Trimble, V. (2010). "Public reaction to a V = -12.5 supernova". The Observatory. 130: 167. Bibcode:2010Obs...130..167H.

- ↑ Ireland, M. J.; et al. (May 2004). "Multiwavelength diameters of nearby Miras and semiregular variables". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 350 (1): 365–374. arXiv:astro-ph/0402326. Bibcode:2004MNRAS.350..365I. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07651.x.

- ↑ A. Richichi (April 1990). "A new accurate determination of the angular diameter of Antares". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 230 (2): 355–362. Bibcode:1990A&A...230..355R.

- ↑ Perryman, M. A. C.; Lindegren, L.; Kovalevsky, J.; Hoeg, E.; Bastian, U.; Bernacca, P. L.; Crézé, M.; Donati, F.; Grenon, M.; Grewing, M.; van Leeuwen, F.; van der Marel, H.; Mignard, F.; Murray, C. A.; Le Poole, R. S.; Schrijver, H.; Turon, C.; Arenou, F.; Froeschlé, M.; Petersen, C. S. (July 1997). "The HIPPARCOS Catalogue". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 323: L49–L52. Bibcode:1997A&A...323L..49P.

- ↑ Percy, John R.; Sato, Hiromitsu (2009). "Long Secondary Periods in Pulsating Red Supergiant Stars". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 103: 11. Bibcode:2009JRASC.103...11P.

- 1 2 Star Maps created using XEphem (2008). "LASCO Star Maps (identify objects in the field of view for any day of the year)". Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph Experiment (LASCO). Retrieved 2011-12-01. (2009, 2010, 2011)

- ↑ "Occultation of Antares on 31 July 09". The International Occultation Timing Association. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ↑ "Sky watchers report occultation of Antares by moon". The Times Of India. 2 August 2009.

- ↑ "Antares overlooking an Auxiliary Telescope". www.eso.org. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ↑ Dave, Gault,; Brian, Loader, (September 2006). "Determining the Separation and Position Angle of Antares A-B during Lunar Occultation". Southern Stars. 45 (3). Bibcode:2006SouSt..45c..14G. ISSN 0049-1640.

- ↑ https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Grant,_James_William_(DNB00)

- ↑ Schaaf, Fred (2008). The Brightest Stars: Discovering the Universe Through the Sky's Most Brilliant Stars. John Wiley and Sons. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-471-70410-2.

- ↑ Kaler, James. "Antares". Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ↑ Burnham, Robert, Jr. (1978). Burnham's Celestial Handbook. New York: Dover Publications. p. 1666.

- 1 2 S.J. Johnson, "Occultation of Antares." The Observatory, Vol. 3, pp. 84-86 (1879)

- ↑ Hartkopf, W.I.; Mason, B.D.; Worley, C.E. (2001). "The 2001 US Naval Observatory Double Star CD-ROM. II. The Fifth Catalog of Orbits of Visual Binary Stars". The Astronomical Journal. 122 (6): 3472–3479. Bibcode:2001AJ....122.3472H. doi:10.1086/323921.

- ↑ Reimers, D.; Hagen, H. -J.; Baade, R.; Braun, K. (2008). "The Antares emission nebula and mass loss of α Scorpii A". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 491: 229–238. arXiv:0809.4605. Bibcode:2008A&A...491..229R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809983.

- ↑ Firestone, R. B. (July 2014), "Observation of 23 Supernovae That Exploded <300 pc from Earth during the past 300 kyr", The Astrophysical Journal, 789 (1): 11, Bibcode:2014ApJ...789...29F, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/789/1/29, 29". See p. 10."

- ↑ Rogers, J. H. (February 1998). "Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (1): 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- ↑ Kunitzsch, P. (1959). Arabische Sternnamen in Europa. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrasowitz. p. 169.

- ↑ Allen, R. H. (1963): According to Charles François Dupuis, a French astronomical writer

- ↑ Mudrooroo (1994). Aboriginal mythology : an A-Z spanning the history of aboriginal mythology from the earliest legends to the present day. London: HarperCollins. p. 5. ISBN 1-85538-306-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Antares. |