Anatoly Rubin

| Anatoly Rubin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | אנטולי רובין |

| Born |

Anatoly (Yitzhak) Rubin 29 January 1927 Minsk, Byelorussia, USSR |

| Died |

16 January 2017 (aged 89) Jerusalem, Israel |

| Nationality | Israeli |

Anatoly (Yitzhak) Rubin was a survivor of the Holocaust and later of the Gulags.[1] Born in Minsk, in what was then the USSR, he survived the German invasion of the USSR in a remote village and was almost killed while trying to join the Partisans. He spent six years in gulags in Siberia for distributing books sympathetic to Zionism. After being under investigation by the KGB for spreading Zionist ideas, he emigrated to Israel in 1969. Once there, he campaigned for the Israeli government to do more to assist others who wished to migrate from the USSR to Israel[2]. He also wrote published memoirs of his earlier experiences. He died in Jerusalem in 2017.

Biography

Early years

Anatoly Rubin was born in Minsk, Byelorussia (later Belarus), on 29 January 1927. His father was religiously observant, and his mother maintained some traditions out of respect for him. Still, Anatoly was more attracted to Russian role models, as opposed to Jewish ones.

In the summer of 1941, when the Wehrmacht invaded the Soviet Union, by way of Minsk, and upon Anatoly's return from summer camp, he was forced to join the stream of refugees deeper into Russia, and was strafed by the Luftwaffe. After two days, he reached the town of Smilovichi, some 35 kilometres from Minsk. There Anatoly was reunited with his aunt and her small son. The three of them stayed there with a Jewish blacksmith, until the Germans occupied the town, preventing prior plans to move further east, and they were forced to return to occupied Minsk. There they found a second aunt along with his mother, and two sisters with her. Anatoly's father was at work away from home when the invasion occurred, and upon his return to Minsk was told that his family had fled towards Moscow; he was murdered by bandits during his search for his family.

In Minsk, as part of the German invasion, legislation caused displacement into the Minsk ghetto. Anatoly's family lived with two other families, in two small rooms. They obtained their daily necessities, at great risk from German sentries, by bartering their aunt's belongings through the ghetto fence. Their situation was alleviated by his sister Tamara whose Aryan looks allowed her to pass as a non-Jew.

In November 1941, the Germans began the liquidation of the ghetto. The residents, his family among them, were marched off to the killing pit. However, Anatoly and his older sister Tamara managed to escape.[3] Tamara joined the partisans and he fled to the 'Aryan' part of the town where, beset by the hatred and physical abuse by the locals,[4] he tried to survive.[5] In the end, he returned to the ghetto, where he lived at first with aunts and worked on the forced labor crews.[6]

In March 1942,[7] as his labor crew was filing back into the ghetto, they were halted by SS men, who were implementing a round of selektion, and was able to narrowly escape back to the ghetto, where some of the remaining residents provided a cellar for him to hide in.[8] The next day, he returned to his own house. By day, he continued to work on the forced labor crews, since laborers were fed 30 grams of bread and a ladle of soup for their efforts. By July 1942, the majority of the ghetto's Jews had been murdered.

Before the ghetto was finally liquidated on 21 October 1943,[9][10][11] a maid who had worked in his school, a German woman married to a local man, smuggled Anatoly out to relatives of her husband, in an outlying village. He succeeded by using Aryan papers that he had received from another friend, also a local ethnic German. Anatoly was now able to live and work in the village as a non-Jew, doing farm work and cow-herding. Partisans, out of suspicion of being a German spy, almost killed him.[lower-alpha 1][13][14]

In the spring of 1944, the Red Army liberated his village. He destroyed his Russian papers and returned to Minsk, where he discovered that not a single member of his family remained alive. His attempt to enlist in the Red Army were refused on the grounds of being underage. Instead, he enrolled in a trade school, which provided its students bed, board and employment.[15]

First incarceration

Rubin was sent by the local Boxing Federation to take part in a national exhibition of physical culture in Red Square in Moscow. On his return (14 November 1946), he was arrested and jailed for abandoning a military facility. A military court sentenced him to five years 're-education' `in a labor camp for his 'nationalist' (i.e. Jewish) views, his unhealthy opinions about the Soviet regime, and his destructive influence on the local youth.[16]

Life in prison was oppressive.[17] There was a significant class-gap between the 'regular' and the criminal prisoners. The latter carried on their own terror regime, and effectively ruled prison life. Rubin instigated an uprising against them. He was transferred to a labor camp. The regime at these camps was a combination of hunger, physical abuse and hard forced labor. A niece heard of his imprisonment and sought his release. She eventually reached a top-ranking general who ordered a review of his case. His sentence was changed to a twelve-month probation. Back in Minsk, he entered The Institute of Physical Culture, which provided generous stipends, larger food rations and even an array of sportswear. His boxing studies were successful. He won fight after fight and steadily built up his physical strength, further motivated by the fact that he could now effectively defend himself against anti-Semitic attacks, which came from many directions.[18]

Awaking of national identity

The ongoing anti-Semitism which Rubin encountered from local Russians steadily fashioned his Jewishness.[19][20][21] He came to understand that he was unwelcome in Russia, and that if he was ever to have a home it could only be in the State of Israel. He now devoted all of his energy and resources toward that goal.

In 1955, while in Riga for a boxing tournament, he first encountered Jews who observed Jewish customs, holidays and traditions. As Soviet rule in Latvia only dated to the Second World War, Jewish activists, especially in Beitar, were still open and active. Well-stocked Jewish libraries were also available.[22] Determined to expand his Jewish knowledge upon his return, he discovered written material of Jewish interest in the central library. He studied and began to openly refer to material in his conversations concerning the ubiquitous Russian Hatred of Jews. Young Minsk Jews were also interested in Gromyko's and Cherepakhin's speeches about the establishment of the new state of Israel, with which Russia then enjoyed warm relations. Anatoly would push to awaken their interest in Jewish life and in the State of Israel. In 1956 he first encountered foreign tourists. He also described to them what it was like to be a Jew in the USSR, with its constant waves of anti-Semitism. He asked them to relay this to the United States and Israel, all of these conversations were recorded by the KGB.

In 1957, an international Youth Festival was held in Moscow. Rubin, along with Jews from throughout Russia, approached the Israeli delegation. These Soviet Jews surrounded the Israelis and could not stop asking them questions. He himself photographed the delegation and the Israeli flag.[23] Rubin met the delegation head, in order to obtain material for the Jewish youth in Minsk. Since the delegation was being monitored by the KGB, the exchange of material could not take place. He still managed to accumulate a significant quantity of literature, which he used extensively in Minsk. His enthusiasm for Jewish things led him to ignore the rules of caution.

Interrogation, investigation and trial

The KGB was closing in, and he was arrested. He refused to incriminate those who shared in his Jewish activities, and he managed to dispose of secret information that was on his person. At interrogation it became apparent that the KGB had amassed detailed and accurate information on him and on his friends and relatives.(After his trial, one of his relatives told him that a listening device had been hidden in the attic above his apartment.) Evidence obtained by bugging and photographing was not admissible in a court of law, and he believed that this legality would be observed. Yet, the greater part of the charges brought against him were based precisely on this "inadmissible evidence". Despite the various 'methods' of interrogation employed against him, Rubin never broke. He gave up not a single name, and admitted to nothing.

The official list of the charges was treason, attempted assassination of a senior party leader and government minister, (in this case, the Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev), anti-Soviet propaganda, dissemination of Zionist literature, ties with the Israeli embassy and the inflaming of nationalist passions. Two weeks into his interrogation a new investigator arrived whose assignment was to persuade Rubin to denounce Israeli embassy staff for conducting subversive activities, under the guise of diplomatic activity. Rubin refused and no further attempt was ever made to recruit him as a collaborator.

Two others had been arrested along with Rubin. One was the wrestling champion of the Minsk republic, to whom Jewish refugees from Minsk had given Israeli literature, along with a sealed package to take back to Rubin. The wrestler did as he was asked, without checking to see what he was carrying. Both Rubin and the wrestler told this to the interrogators, even though they had not coordinated their testimony. Rubin's second co-accused was a doctor, the son of a veteran communist with long years of underground activity to his credit, including interest in Zionism. Rubin had viewed him as a potential ally and gave him material which the doctor distributed. Once arrested, he broke immediately, writing a letter of confession and penitence, and placed all the blame on Rubin. Rubin accepted all responsibility for acts which had been proved against the doctor. He explained that he adopted this course of action, because in his eyes the issue was not his own actions but his conviction that all three of the accused were perceived to be representatives of Zionist Jewry. For this reasons, he declared it was important to him that he retain his dignity, proving for once and for all that Jews were people of steadfast principle, and neither cowards nor traitors.

The most dangerous of the charges against him was that of attempted assassination of Premier Khrushchev, since that carried the death penalty. He was endlessly questioned on this point, and had persisted in his absolute denials. He refused to accept the court-appointed defense lawyer to defend him, preferring to defend himself. Nevertheless, the court appointed a defense attorney, the chairman of the Byelorussian bar. The trial lasted five months, for four of which he was held in solitary confinement. (The treason charge was dropped during the interrogation.)

The proceedings were all carried on behind closed doors, to prevent them from being used by Rubin for advancement of his ideas. He pleaded not guilty to all the charges against him (in contrast with his co-defendants, who immediately pleaded guilty). He admitted that the literature that was found in his possession was his, however, he asserted that he did not regard the materials as being anti-Soviet. His court appointed lawyer admitted that he was guilty of grave crimes, although he endeavored to mitigate the verdict by recounting his life history: that during the war he had been held in a ghetto and orphaned at the age of 13; that the anti-Semitic Fascist Nazis had slaughtered his whole family, which accounted for his adult sensitivity to anti-Semitism; that brushes with a few anti-Semitic hooligans since then had left him over-sensitive, which Zionist propaganda had then exploited. Twenty witnesses testified at the trial. In his closing remarks, the prosecutor asked that Rubin be sentenced to five years re-education in a labor camp as the organizer of a criminal cell. The doctor was sentenced to two years and expulsion from the Communist Party and the wrestler to six months. The trial lasted six months, till 29 April 1959; the KGB's file No.19121-s about the trial and the sentence is in Minsk.[24]

In his closing remarks, Rubin defended his actions, highlighted state-sanctioned anti-Semitism and the suppression of the Jews' national life. He declared his goal to leave for his homeland, Israel. His defense lawyer had assumed that he would not get more than three years. However, after Anatoly's speech, the judges reconsidered and sentenced him to six years; the KGB's file about this is in Moscow.

Return to the gulag

In order to poison the atmosphere, the KGB had spread the word that he had planned to blow up the Minsk hotel; that he had been caught in the company of an agent who had given him information to take to the West; and that a half million rubles in foreign currency were found in his possession. Everything about the gulags was familiar there from his ten years before, except that the majority of prisoners were now political internees. He was first sent to Lagopunkt 11,[25] next to the Yaya train station.[26] The inmate population mostly Nazi war criminals ( e.g. Gestapo investigators). When asked what they were in for and their inevitable answer was, "Because of the Yids". During the last three years of his sentence (1962–1965), he was interned at Lagopunkt 10[25] where all prisoners wore striped overalls, were held in cells after work, and denied the 'privilege' of walking around the camp grounds. The rations were also several grades severer than in other camps.

Ten percent was composed of Jews. Some were revisionists. Some had denounced Soviet anti-Semitism. Others, like Rubin, had been convicted of Zionist activism. These last came from every corner of the Soviet Union. Rubin had thought that he was alone but, under Rubin's leadership, all the Jews in the camp were united and of one mind on Israel. They met to exchange information. Veteran Zionists shared history, culture and traditions. Some knew Hebrew and began giving lessons. They compiled their own small dictionaries by taking Russian primers and writing the Hebrew for each Russian word above it. They composed and learned by heart frequently used sentences. They celebrated every Jewish holiday. For this activity, which was forbidden both within the camp and in the USSR generally, they would gather in one of the clothing storerooms to hear one of the older inmates recite the prayers. As far as was possible they observed the commandments, and on Yom Kippur every one fasted, religious and secular alike. For them this was not only a religious observance, but a demonstration of national unity. They fashioned old silver coins into Magen David pendants, which they wore under their shirt. Collaboration was not tolerated. Among the Jewish political inmate there was an unwritten, iron-clad law that no one was to join any officially organized structure in any way. Anyone who did so was immediately totally ostracized.[27]

Rubin paid a price for this policy. Circumstances offered a prospect for Rubin's early release. The camp commandant informed him that as commandant, he had to draw up a prisoner assessment and he included him in a list of inmates who were willing to undertake "public activity". Upon hearing this, Rubin angrily demanded that his name be removed from this "blacklist". He added that he would not let them use him for any of their dirty business. Two weeks later, the Prosecutor General informed him that he would never be eligible for commutation of his sentence. The file of the KGB about those six years is in Moscow.[24]

Leon Uris' Exodus

The prisoners made great efforts to obtain reading materials. One of the prisoners in Rubin's camp was a well-known writer who was allowed to receive books. He was friendly with many Jewish inmates, and defended them against anti-Semitic assaults. He told Rubin that he had received a book in English called Exodus and that he would find it interesting. Other Jewish inmates immediately organized a group reading. Rubin had the book disguised as a Soviet textbook. The book was passed from hand to hand, and smuggled by Anatoly in the transfers to other camps. In one of these camps, a Jew undertook its translation into Russian. Immediately upon its completion, Anatoly had it smuggled out to the world beyond the camps. There, in samizdat form, it fulfilled a critical and formative role in the awakening the national consciousness of Soviet Jewry.

Release from the Gulag and return to Minsk

As the prospect of his release came closer, his health began to falter as a result of the endless stress of hunger rations, physical strain, and inhuman conditions. Throughout the spring of 1964, the inmates worked standing in pools of freezing melt-water, as a result, pain in his feet and legs built up until he could hardly sleep at night. His release date had been set for Tuesday, 8 December 1964. The camp authorities offered him an early release on condition that he sign an application for a pardon, which was effectively an admission of guilt, which as usual he declined. Upon his release, he later stated, "I was stepping out into the biggest prison camp of them all—the Soviet Union itself".

Rubin had friends in Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, Riga and elsewhere. Friends introduced him into their circles. After four days in Moscow, he traveled to Minsk and then to Riga. He met with youth, attended the synagogue and visited Rombula ravine where the Jews of Riga had been massacred. When he left for the station, it was clear that the KGB was shadowing him. He boarded one coach and moved to another, certain that the KGB would be waiting for him in Minsk. The agent did not find him and decided that Anatoly had eluded him. When he arrived at his Minsk apartment, a police agent appeared to record his address.

Zionist activity in Minsk and departure from Russia

Upon returning to Minsk, Rubin found himself unemployable. A month later, he was informed that the charges against him had been unfounded and he was fully rehabilitated. This was apparently a result of the fall of Khrushchev in October 1964. He was soon employed by the Minsk Municipal Hospital as a senior physical exercise teacher. At the same time, he set up activities to teach the city's Jews about Judaism and the State of Israel. Soon he had created a cadre committed to Jewish national revival.[28] Knowing that he was a KGB target, he was careful not to endanger them. He compartmentalized all those involved, and the lines of distribution of material. Several times it even happened that someone would approach him and suggest, in absolute secrecy, that he give him a booklet to read that he himself had put into circulation. Ze'ev Jabotinsky's writings were especially popular. Rubin himself translated them into Russian and ensured there was a wide circulation[29]

To obtain material, Rubin traveled to other towns, where he had friends from the camps. In order to justify these visits, he took advantage of Soviet regulations that allowed anyone who donated blood to receive two days vacation. Anatoly combined these with his regular, weekly day of rest, resulting in three-day trips away from Minsk. On a trip to Riga, he learned that the KGB was investigating him. He warned his contacts to dispose of anything incriminating. Almost every friend and contact of Anatoly was detained and questioned by the KGB. Finally, his own turn came. He decided to deny everything, because in Russia a 'no' always remained a 'no'. He was interrogated for five days, from morning to evening. On the sixth day, the agents confronted him with a friend, who it emerged had revealed everything he knew. Anatoly violated the rules of interrogation by jumping up and declaring that everything was a lie. Faced with Rubin's refusal to admit anything, the chief interrogator closed the investigation against him.

Soon after, the authorities in Riga started issuing exit permits for Israel to selected Jews. He traveled to Riga and asked friends who had received permits to try to obtain an official invitation for him to immigrate once they reached Israel. Such an invitation did arrive and the OBIR, actually registered the invitation. Rubin was summoned to OBIR and informed by its director: “You have been granted a travel permit. It's better you go to this Israel of yours than stay here poisoning the minds of Soviet youth". Rubin was the first Jew from Minsk to receive an emigration permit after the Six Day War. He was given twelve days to leave, during which time he traveled to bid farewell to friends. A large crowd came to the train station to see him off in person. There were speeches, and Israeli songs and dances. Many Jews sent him their names and addresses, asking that they too be sent an official invitation to make aliyah. They sent the message that Israel do all in its power to help them leave the Soviet Union.

In Israel

Rubin landed in Israel on 1 May 1969, and was sent to an absorption center in the northern town of Carmiel. There he found a large group of Russian Zionist activists who, like him, had been allowed to leave as part of the KGB's attempt to break the movement of Jewish and Zionist national revival. Passionate in their conviction that the time had come for open and public action against all attempts to halt the emigration from the USSR he and his friends, Joseph Khrul and Joseph Schneider, wrote to the prime minister, Golda Meir, and were soon invited to talks at her office in Tel Aviv.

The meeting was crowded, because an 18-strong group from Georgia had also been invited, along with attorney Lidia Slovina and her husband, themselves Zionist activists from Riga. The attendees all wanted to know why more was not being done to get Russian Jews out of the USSR. They then set out their reasons for adopting drastic measures to achieve that goal, especially organizing demonstrations around the world. The Prime Minister explained to them that Israeli current policy was to maintain public silence on the question. Recent experience with Romania seemed to support such an approach. The Romanian Communist regime had been quietly persuaded to release its Jews. However, as soon as their emigration was made public, the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu put a stop to it.

Upon emerging from the meeting, the attendees concluded that they would have to take action themselves. Two of them at once, at their own expense, flew to the United States to arouse public opinion there. At the same time, NATIV (a department of Israel's Foreign Ministry that was tasked with fostering Jewish education and awareness behind the Iron Curtain, and in facilitating emigration to Israel) decided to send two representatives of its own to America to do the same. The first was Joseph Khrul, he was followed soon thereafter by Anatoly Rubin. At the time, the media was prohibited from publishing the names of those who had left the USSR (along with the fact that anyone was getting out at all). One American journalist, though, had not heard of the prohibition and published Anatoly's name and everything he told them.

Back in Israel, when Russian Aliyah activists failed to persuade either NATIV or the Israeli Government to do more, they declared a hunger strike in front of the Wailing Wall. NATIV strongly opposed this move. It proved, however, to be the crucial push that set the movement to 'Let my People Go' in motion. Rubin, Joseph Khrul, Joseph Schneider and Asher Blank were all enlisted by NATIV to act as its advisers. In the camps, Anatoly had felt a deeply and painful sense of aloneness and despair at the lack of outside support. He never forgot the activists' plea to him that Israel will not remain silent, but rather do all in its power to help them get out. He was determined to rally worldwide support and break down the wall of silence.

He had also begun teaching physical education in Israel, at first in schools and then at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The link between physical fitness and national pride, which had accompanied him for so many years, continued to drive him. In addition, he devoted a lot of time to educating Israel's youth to develop pride in their Jewish heritage and in Zionism.

Anatoly was determined that his experiences in the Holocaust and the Gulags of the Soviet Union should not be forgotten, and would serve to instruct future generations. This led him to write his memoirs. He wrote them first in Russian, a work for which he shared first prize in a nation wide competition, 'My Path to the Land of Israel', which he was awarded in 1975, by the Israeli President, Ephraim Katzir. The book was then translated into Hebrew and published in 1977 by Dvir Publishing, under the name "Brown Boots, Red Boots—from the Minsk Ghetto to the Siberian Labor Camps". After his death in 2017, the famed Israeli author Galila Ron-Feder Amit reworked the translation of his book. This version of his book will be published soon. Galila Ron-Feder Amit was already very familiar with Rubin's life. In 2004, she had written and immortalized Anatoly in her book Prisoner of Zion, a Journey to the USSR of the Early Sixties and Prisoner of Zion Anatoly Rubin, the 26th volume of the Time Tunnel series.

Above all, Anatoly continued his work. In 1989, he was sent by NATIV to the USSR, and in particular to Minsk, to encourage Aliyah. Over the next two years many Minsk and Leningrad Jews followed him to Israel.

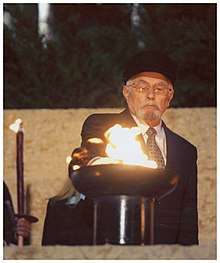

In 2012, he was honored to light one of the six memorial torches at the National Observance of Holocaust Memorial Day at Yad VaShem in Jerusalem.[30][31]

Family

In 1969, after he made aliyah, his daughter Ilona was born in the Soviet Union (and later two grandchildren Polina and David). The family lives in Atlanta, United States.

In 1972, Rubin married Karny Jabotinsky Rubin[32]. They had two children, Eri and Tamar, and later three grandchildren, Yoav, Maya-Shai and Itamar.

Anatoly Rubin died on 16 January 2017,[33][34] and was buried in the Kiryat Anavim cemetery, near Jerusalem. [35]

Notes

References

- ↑ "Anatoly Rubin as one of Prisoners of Zion".

- ↑ "Anatoly Rubin as one of Prisoners of Zion".

- ↑ Anatoly Rubin's story is written in Barbara Epstein's book "The Minsk Ghetto 1941–1943: Jewish Resistance and Soviet Internationalism"

- ↑ Bankier, David; Gutman, Israel (23 March 2018). "Nazi Europe and the Final Solution". Berghahn Books – via Google Books.

- ↑ Dean, Martin (23 March 2003). "Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941–44". Palgrave Macmillan – via Google Books.

- ↑ Labor forced work in the Minsk ghetto

- ↑ Rubin (1977), pp. 21–27.

- ↑ אדרת, עופר (23 March 2018). "מהגטו לסיביר: סיפור ההישרדות של אנטולי רובין" – via Haaretz.

- ↑ "Wayback Machine". 3 September 2011.

- ↑ Himka, John-Paul; Michlic, Joanna Beata (1 July 2013). "Bringing the Dark Past to Light: The Reception of the Holocaust in Postcommunist Europe". U of Nebraska Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Jewish armed resistance in ghettos and camps, 1941–1944". www.ushmm.org.

- ↑ Smilovitskii, Leonid: Antisemitism in the Soviet Partisan Movement, 1941–1944: The Case of Belorussia in: Holocaust and Genocide Studies 20, 2006

- ↑ Smilovitsky, Leonid (2000). "Anti-Semitism in the Partisan Movement of Belorussia, 1941-1944". Katastrofia Evreev v Belorusii 1941-1944 [Holocaust in Belorussia, 1941-1944]. Translated by Judith Springer. Tel Aviv: Biblioteka Motveya Chernogo. pp. 147–.

- ↑ Rubin (1977), pp. 37–41.

- ↑ Redlich, Shimon; Anderson, Kirill Mikhaĭlovich; Alʹtman, I. (23 March 1995). "War, Holocaust and Stalinism: A Documented Study of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in the USSR". Psychology Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ Rubin (1977), pp. 47–51.

- ↑ Rubin (1977), pp. 51–60.

- ↑ Земсков В.Н. К вопросу о репатриации советских граждан. 1944–1951 годы // История СССР. 1990. № 4 (Zemskov V.N. On repatriation of Soviet citizens. Istoriya SSSR., 1990, No.4

- ↑ Rubin (1977), pp. 74–79.

- ↑ "Doctors' Plot – Soviet history".

- ↑ Rapoport (1991), pp. 119–120

- ↑ "LATVIA".

- ↑ פנכוס, בנגאמין; פינקוס, בנימין (23 March 1993). "תחייה ותקומה לאומית: הציונות והתנועה הציונית בברית־המועצות, 1947־1987". המרכז למורשת בן־גוריון – via Google Books.

- 1 2 RUBIN ANATOLY PINKHUSOVICH in the list of VICTIMS OF POLITICAL TERROR IN THE USSR, as cited by the Memorial Society on the basis of the Memory Books issued or prepared for release in various regions of the former USSR, as well as a number of unpublished sources

- 1 2 Map of Gulag camp administrations and stories from Central Europe

- ↑ "Карта посёлка Яя, Яйский район, ближайшие города". tochka-na-karte.ru.

- ↑ Ron Fedder Amit (2004), pp.38–46

- ↑ כהן, דוד; אבן-שושן, שלומו (23 March 1985). "מינסק עיר ואם". Irgun yotsʼe Minṣk u-venoteha be-Yiśraʼel – via Google Books.

- ↑ Schroeter, Leonard (23 March 1979). "The Last Exodus". University of Washington Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Anatoly Rubin - www.yadvashem.org". www.yadvashem.org.

- ↑ "Yad Vashem - Yad Vashem Magazine No. 65 - Page 4-5 - Created with Publitas.com". view.publitas.com.

- ↑ [Daugther of Eri Jabotinsky.]

- ↑ "Misrad Haklita on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- ↑ אדרת, עופר (2017). "מהגטו לסיביר: סיפור ההישרדות של אנטולי רובין". הארץ (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- ↑ "He fought the devil and won".

Publications

- The following publication by Anatoly Rubin is referenced in this article.

- Rubin, Anatoly (1977), My way to Eretz Israel [A page from an endured life, chapter No.2] (in Russian), Jerusalem, pp. 84–250 – via written August 1972, Jerusalem Ha'aliya Library

- Rubin, Anatoly (1977), Brown Boots Red Boots [From the Ghetto of Minsk to the Camps of Siberia] (in Hebrew), Tel-Aviv, pp. 9–185 – via Dvir Co. Ltd

Further reading

- Epstein, Barbara (2006). Antisemitism in the Soviet Partisan Movement, 1941–1944: The Case of Belorussia in: Holocaust and Genocide Studies 20. .

- Epstein, Barbara (2008). The Minsk Ghetto 1941–1943: Jewish Resistance and Soviet Internationalism. ISBN 9780520242425. .

- Smilovitskii, Leonid (2008). The Minsk Ghetto 1941–1943: Jewish Resistance and Soviet Internationalism. New York: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24242-5. .

- Rapoport, Yakov (1991). The Doctors' Plot of 1953: A Survivor's Memoir of Stalin's Last Act of Terror Against Jews and Science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674214774. .

- Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr Isaevich (1962). One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Soviet Union: Signet Classic Press. ISBN 0374529523. .

- Ron Fedder Amit, Galilah (2004). the tunnel of time 26 - prisoner of zion (in Hebrew). Ben-Shemen: Modan publishing house Ltd.

- Arkady Vaksberg (1994). Stalin Against The Jews, tr. Antonina Bouis. ISBN 0-679-42207-2

- Louis Rapoport (1990). Stalin's War Against the Jews. ISBN 0-02-925821-9