Alnwick Castle

| Alnwick Castle | |

|---|---|

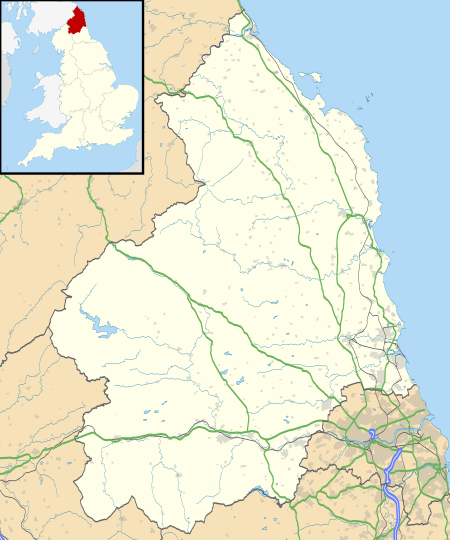

| Alnwick, Northumberland | |

Alnwick Castle | |

Alnwick Castle | |

| Coordinates | 55°24′57″N 1°42′22″W / 55.41575°N 1.70607°W |

| Site information | |

| Owner | The 12th Duke of Northumberland |

| Site history | |

| Built |

11th century |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 1 January 1985 |

| Reference no. | 1001041[1] |

Alnwick Castle (/ˈænɪk/ (![]()

History

Alnwick Castle guards a road crossing the River Aln.[4] Yves de Vescy, Baron of Alnwick, erected the first parts of the castle in about 1096.[5] Beatrix de Vesci, daughter of Yves de Vescy married Eustace Fitz John, Constable of Chestershire and Knaresborough. By his marriage to Beatrix de Vesci he gained the Baronies of Malton and Alnwick. The castle was first mentioned in 1136 when it was captured by King David I of Scotland.[6] At this point it was described as "very strong".[4] It was besieged in 1172 and again in 1174 by William the Lion, King of Scotland and William was captured outside the walls during the Battle of Alnwick.[7] Eustace de Vesci, lord of Alnwick, was accused of plotting with Robert Fitzwalter against King John in 1212.[8] In response, John ordered the demolition of Alnwick Castle and Baynard's Castle (the latter was Fitzwalter's stronghold);[9] however, his instructions were not carried out at Alnwick.[10]

The castle had been founded in the late 11th century by Ivo de Vesci, a Norman nobleman from Vassy, Calvados in Normandy. Descendent of Ivo de Vesci, John de Vesci succeeded to his father's titles and estates upon his father's death in Gascony in 1253. These included the barony of Alnwick and a large property in Northumberland and considerable estates in Yorkshire, including Malton. Due to being under age, King Henry III of England conferred the wardship of John's estates to a foreign kinsmen, which caused great offence to the de Vesci family. The family's property and estates had been put into the guardianship of Antony Bek, who sold them to the Percys. From this time the fortunes of the Percys, though they still held their Yorkshire lands and titles, were linked permanently with Alnwick and its castle and have been owned by the Percy family, the Earls and later Dukes of Northumberland since.[11] The stone castle Henry Percy bought was a modest affair, but he immediately began rebuilding. Though he did not live to see its completion, the building programme turned Alnwick into a major fortress along the Anglo-Scottish border. His son, also called Henry (1299–1352), continued the building.[12] The Abbot's Tower, the Middle Gateway and the Constable's Tower survive from this period.[11] The work at Alnwick Castle balanced military requirements with the family's residential needs. It set the template for castle renovations in the 14th century in northern England; several palace-fortresses, considered "extensive, opulent [and] theatrical" date from this period in the region, such as the castles of Bamburgh and Raby.[13] In 1345 the Percys acquired Warkworth Castle, also in Northumberland. Though Alnwick was considered more prestigious, Warkworth became the family's preferred residence.[14]

The Percy family were powerful lords in northern England. Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland (1341–1408), rebelled against King Richard II and helped dethrone him. The earl later rebelled against King Henry IV and after defeating the earl in the Battle of Shrewsbury, the king chased him north to Alnwick. The castle surrendered under the threat of bombardment in 1403.[15]

During the Wars of the Roses, castles were infrequently engaged in battle and conflict was generally based around combat in the field. Alnwick was one of three castles held by Lancastrian forces in 1461 and 1462, and it was there that the "only practical defence of a private castle" was made according to military historian D. J. Cathcart King.[16] It was held against King Edward until its surrender in mid-September 1461 after the Battle of Towton. Re-captured by Sir William Tailboys, during the winter it was surrendered by him to Hastings, Sir John Howard and Sir Ralph Grey of Heton in late July 1462. Grey was appointed captain but surrendered after a sharp siege in the early autumn. King Edward responded with vigour and when the Earl of Warwick arrived in November Queen Margaret and her French advisor, Pierre de Brézé were forced to sail to Scotland for help. They organised a mainly Scots relief force which, under George Douglas, 4th Earl of Angus and de Brézé, set out on 22 November. Warwick's army, commanded by the experienced Earl of Kent and the recently pardoned Lord Scales, prevented news getting through to the starving garrisons. As a result, the nearby Bamburgh and Dunstanburgh castles soon agreed terms and surrendered. But Hungerford and Whittingham held Alnwick until Warwick was forced to withdraw when de Breze and Angus arrived on 5 January 1463.

The Lancastrians missed a chance to bring Warwick to battle instead being content to retire, leaving behind only a token force which surrendered next day.

By May 1463 Alnwick was in Lancastrian hands for the third time since Towton, betrayed by Grey of Heton who tricked the commander, Sir John Astley. Astley was imprisoned and Hungerford resumed command.

After Montagu's triumphs at Hedgeley Moor and Hexham in 1464 Warwick arrived before Alnwick on 23 June and received its surrender next day.

After the execution of Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of Northumberland, in 1572 Alnwick castle was uninhabited.[12] In the second half of the 18th century Robert Adam carried out many alterations. The interiors were largely in a Strawberry Hill gothic style not at all typical of his work, which was usually neoclassical.

However, in the 19th century Algernon, 4th Duke of Northumberland replaced much of Adam's architecture. Instead he paid Anthony Salvin £250,000 between 1854 and 1865 to remove the Gothic additions and other architectural work. Salvin is mostly responsible for the kitchen, the Prudhoe Tower, the palatial accommodation, and the layout of the inner ward.[17] According to the official website a large amount of Adam's work survives, but little or none of it remains in the principal rooms shown to the public, which were redecorated in an opulent Italianate style in the Victorian era by Luigi Canina.

Current use

The current duke and his family live in the castle, but occupy only a part of it. The castle is open to the public throughout the summer. After Windsor Castle, it is the second largest inhabited castle in England.[10][18] Alnwick was the tenth most-visited stately home in England according to the Historic Houses Association, with 195,504 visitors in 2006.[19]

Since World War II, parts of the castle have been used by various educational establishments: firstly, by the Newcastle upon Tyne Church High School; then, from 1945 to 1977, as Alnwick College of Education, a teacher training college; and, since 1981, by St. Cloud State University of Minnesota as a branch campus forming part of their International Study Programme.

Special exhibitions are housed in three of the castle's perimeter towers. The Postern Tower, as well as featuring an exhibition on the Dukes of Northumberland and their interest in archaeology, includes frescoes from Pompeii, relics from Ancient Egypt and Romano-British objects. Constable's Tower houses military displays like the Percy Tenantry Volunteers exhibition, local volunteer soldiers raised to repel Napoleon's planned invasion in the period 1798–1814. The Abbot's Tower houses the Regimental Museum of the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers.[20]

An increase in public interest in the castle was generated by its use as a stand-in for the exterior and interior of Hogwarts in the Harry Potter films.[10] Its appearance in the films has helped shape the public imagination regarding what castles should look like. Its condition contrasts with the vast majority of castles in the country, which are ruinous and unfit for habitation.[21]

Construction

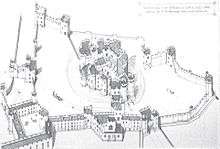

The River Aln flows past the north side of the Castle. There is a deep ravine to the south and east, separating the castle from the town.[22] By the 12th century, Alnwick Castle had assumed the general layout which it retains today. It is distinguished as one of the earliest castles in England to be built without a square keep.[10] The castle consists of two main rings of buildings. The inner ring is set around a small courtyard and contains the principal rooms. This structure is at the centre of a large bailey. As the central block was not large enough to contain all the accommodations required in later centuries, a large range of buildings was constructed along the south wall of the bailey. These two main areas of accommodation are connected by a link building. There are towers at regular intervals along the walls of the outer bailey. About a sixth of the bailey wall has been reduced almost to ground level on the bailey side to open up views into the park. Stable and service yards adjoin the castle outside the bailey; these would not have existed when the castle still had a military function.

Alnwick Castle has two parks. Immediately to the north of the castle is a relatively small park straddling the River Aln which was landscaped by Lancelot Brown ("Capability Brown") and Thomas Call in the 18th century; it is known locally as The Pastures. Nearby is the much larger Hulne Park, which contains the remains of Hulne Priory.

The castle is in good repair and used for many purposes. It provides a home for the present Duke and family and offices for Northumberland Estates, which manages the Duke's extensive farming and property holdings.

Alnwick's battlements are surmounted by carved figures dating from around 1300; historian Matthew Johnson notes that around this time there were several castles in northern England similarly decorated, such as Bothal, Lumley, and Raby.[23]

Alnwick Garden

Adjacent to the castle, Jane Percy, Duchess of Northumberland, has initiated the establishment of The Alnwick Garden, a formal garden set around a cascading fountain. It cost £42 million (press release of 7 August 2003). The garden belongs to a charitable trust which is separate from the Northumberland Estates, but the Duke of Northumberland donated the 42-acre (17 ha) site and £9 million. The garden is designed by Jacques Wirtz and Peter Wirtz of Wirtz International based in Schoten, Belgium. The first phase of development, opened in October 2001, involved the creation of the fountain and initial planting of the gardens. In 2004 a large 6,000 sq ft (560 m2) 'tree house' complex, including a cafe, was opened. It is deemed one of the largest tree houses in the world.

In February 2005, a poison garden, growing plants such as cannabis and opium poppy, was added. May 2006 saw the opening of a pavilion and visitor centre designed by Sir Michael Hopkins and Buro Happold which can hold up to 1,000 people.[24]

As of 2011, there are still several areas to be completed, in order to fulfil the original design.

Filming location

Alnwick Castle has been used as a setting in many films and television series.[25]

- Films

- 1954 Prince Valiant

- 1964 Becket

- 1971 Mary, Queen of Scots

- 1979 The Spaceman and King Arthur

- 1982 Ivanhoe, starring Anthony Andrews and James Mason

- 1990 or 1991 The Timekeeper

- 1991 Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves

- 1998 Monk Dawson

- 1998 Elizabeth

- 2001 Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone

- 2002 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

- 2010 Robin Hood, directed by Ridley Scott

- 2017 Transformers: The Last Knight, directed by Michael Bay

- Television

- 1983 The Black Adder

- 1984–1986 Robin of Sherwood

- 1991 Star Trek: The Next Generation

- 1995 Antiques Roadshow

- 1995 The Fast Show

- 2005 The Virgin Queen

- 2009 Dickinson's Real Deal

- 2011 Red or Black?

- 2012 Flog It!

- 2012 The Hollow Crown

- 2014/2015 Downton Abbey[26]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1001041)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Historic England. "Alnwick Castle (235592)". Images of England. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- ↑ "History museums: Divine detour". The Economist. 27 October 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- 1 2 Pettifer 1995, p. 170

- ↑ Hull 2008, p. 195

- ↑ Cathcart King 1983, p. 325

- ↑ Fry 2005, p. 97

- ↑ Turner 2004

- ↑ Allen Brown 1959, pp. 254–255

- 1 2 3 4 Fry 2005, p. 96

- 1 2 Fry 2005, pp. 96–97

- 1 2 Emery 1996, p. 36

- ↑ Emery 1996, p. 17

- ↑ Goodall 2006, p. 38

- ↑ Pettifer 1995, p. 171

- ↑ Cathcart King 1988, p. 159

- ↑ Historic England. "Alnwick Castle (7152)". PastScape. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ↑ Robinson 2010, p. 7; Mackworth-Young 1992, p. 88

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (3 March 2008). "Doors opened at the treasure house (section: Britain's stately stars)". UK news. The Guardian. London. p. 10. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ↑ "Museum enlists force of model recruits". Northumberland Gazette. 23 September 2004. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ↑ Hull 2008, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Pettifer 1995, p. 172

- ↑ Johnson 2002, p. 73

- ↑ "Alnwick Garden's 'transparent' visitor centre". Europe Travel News. 16 May 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ↑ "Media and filming at Alnwick Castle". Alnwick Castle.

- ↑ "Downton Abbey at Alnwick Castle". Alnwick Castle. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

References

- Allen Brown, Reginald (April 1959), "A List of Castles, 1154–1216", The English Historical Review, Oxford University Press, 74 (291): 249–280, doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxiv.291.249, JSTOR 558442

- Cathcart King, David James (1983), Castellarium Anglicanum: An Index and Bibliography of the Castles in England, Wales and the Islands. Volume II: Norfolk–Yorkshire and the Islands, London: Kraus International Publications, ISBN 0-527-50110-7

- Cathcart King, David James (1988), The Castle in England and Wales: an Interpretative History, London: Croom Helm, ISBN 0-918400-08-2

- Emery, Anthony (1996), Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500, Volume I: Northern England, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-49723-7

- Fry, Plantagenet Somerset (2005) [1980], Castles, Newton Abbot: David & Charles, ISBN 0-7153-7976-3

- Goodall, John (2006), Warkworth Castle and Hermitage, London: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-85074-923-3

- Hull, Lisa (2008), Understanding the Castle Ruins of England and Wales: How to Interpret the History and Meaning of Masonry and Earthworks, McFarland & Co, ISBN 978-0-7864-3457-2

- Johnson, Matthew (2002), Behind the Castle Gate: From Medieval to Renaissance, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-25887-1

- Mackworth-Young, Robin, The History and Treasures of Windsor Castle, Andover: Pitkin, ISBN 0-85372-338-9

- Pettifer, Adrian (1995), English Castles: A Guide by County, Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, ISBN 0-85115-782-3

- Robinson, John Martin, Windsor Castle: The Official Illustrated History, London: Royal Collection Publications, ISBN 978-1-902163-21-5

- Turner, Ralph V. (2004), "Vescy (Vesci), Eustace de (1169/70–1216)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Cockayne's Complete Peerage, (Vescy), Vol. XIIB, pp. 272–274

Further reading

- Dodds, Glen Lyndon (2002), Historic Sites of Northumberland & Newcastle upon Tyne, Albion Press, pp. 18–27

- Johnson, Paul (1989), Castles of England, Scotland and Wales, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-83162-3

- Tate, George (1866), The History of the Borough, Castle, and Barony of Alnwick: Volume I, Alnwick: Henry Hunter Blair

- Willis, Peter (1981), "Capability Brown in Northumberland", Garden History, The Garden History Society, 9 (2): 157–183, JSTOR 1586787

- McDonald, James (2012), Alnwick Castle, Frances Lincoln, ISBN 978-0711232372

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alnwick Castle. |

- Alnwick Castle

- Alnwick Garden

- The Northumberland Fusiliers Museum

- Gatehouse Gazetteer record for Alnwick Castle