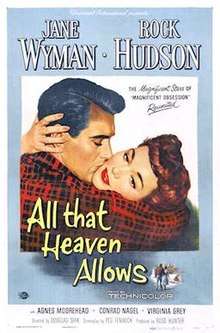

All That Heaven Allows

| All That Heaven Allows | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Douglas Sirk |

| Produced by | Ross Hunter |

| Screenplay by | Peg Fenwick |

| Story by |

Edna Lee Harry Lee |

| Starring |

Jane Wyman Rock Hudson |

| Music by | Frank Skinner |

| Cinematography | Russell Metty |

| Edited by | Frank Gross |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 89 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $3.1 million (US)[3] |

All That Heaven Allows is a 1955 Technicolor drama romance film starring Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson in a tale about a well-to-do widow and a younger landscape designer falling in love. The screenplay was written by Peg Fenwick based upon a story by Edna L. Lee and Harry Lee. The film was directed by Douglas Sirk and produced by Ross Hunter.

In 1995, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

Plot

Cary Scott (Jane Wyman) is an affluent widow in Stoningham in suburban New England, whose social life involves her country club peers, college-age children, and a few men vying for her affection.

She becomes interested in Ron Kirby (Rock Hudson), her gardener, an intelligent, down-to-earth and respectful yet passionate younger man. Ron is content with his simple life outside the materialistic society and the two fall in love. Ron introduces her to people who seem to have no need for wealth and status and she responds positively. Cary accepts his proposal of marriage, but becomes distressed when her friends and college-age children are angry. They look down upon Ron and his friends and reject their mother for this socially unacceptable arrangement. Eventually, bowing to this pressure, she breaks off the engagement.

Cary and Ron continue their separate lives, both with many regrets, but Cary's children soon announce they are moving out. Having destroyed her chance at happiness, her son buys her a television set to keep her company. Before doing so, however, her daughter apologizes to her mother for her prior impulsive and foolish reaction to Ron, saying that there is still time if she really does love Ron. Cary's doctor points out that Cary is now lonelier than she was before meeting Ron.

When Ron has a life-threatening accident, Cary realizes how wrong she had been to allow other people's opinions and superficial social conventions to dictate her life choices and decides to accept the life Ron offers her. As he recovers, Cary is by his bedside telling him that she has returned home.

Cast

- Jane Wyman as Cary Scott

- Rock Hudson as Ron Kirby

- Agnes Moorehead as Sara Warren

- Conrad Nagel as Harvey

- Virginia Grey as Alida Anderson

- Gloria Talbott as Kay Scott

- William Reynolds as Ned Scott

- Charles Drake as Mick Anderson

- Hayden Rorke as Dr. Dan Hennessy

- Jacqueline De Wit as Mona Plash (as Jacqueline de Wit)

- Leigh Snowden as Jo-Ann

- Donald Curtis as Howard Hoffer

- Alex Gerry as George Warren

- Nestor Paiva as Manuel

- Forrest Lewis as Mr. Weeks

- Tol Avery as Tom Allenby

- Merry Anders as Mary Ann

Production notes

Development

Universal-International Pictures wanted to follow up on the pairing of Wyman and Hudson from Douglas Sirk's Magnificent Obsession (1954). Sirk found the screenplay for All That Heaven Allows "rather impossible," but was able to restructure it and use the big budget to film and edit the work exactly the way he wanted.[4]

Wyman was only 38 when she played the film's 'older woman' who scandalizes society and her grown-up children by becoming engaged to a younger man. Hudson, 'the younger man', was 30 at the time.

Music

The music that often plays throughout the film is Consolation No.3 in D-flat major by Franz Liszt along with frequent snatches of the finale to Brahms's First Symphony, the latter rescored and sometimes elaborated .[5] Also heard intermittently is "Warum" by Robert Schumann, from the Fantasiestücke, Op. 12.

Screenplay

Screenwriter Peg Fenwick wrote the screenplay for All That Heaven Allows based on the 394-page novel of the same name by Harry and Edna L. Lee. Notations made on various pages of a copy of the original screenplay owned by the New York Public Library indicate that the script was written in August 1954. Some scenes in the script differ from those the finished film: for instance, in the screenplay Rock Hudson's character, Ron Kirby lies on the grass eating his lunch, but in the final cut of the film he has lunch with Jane Wyman's character, Cary Scott.[6]

Sirk considered having Hudson's character die at the end of the film, but the film's producer, Ross Hunter, would not allow it, as he wanted a more positive ending.

Filming

Some exteriors for the film were shot on “Colonial Street,” a studio backlot built by Paramount Pictures on the property of Universal Studios four years earlier and used in the film The Desperate Hours. The set was re-designed to mimic an upper-middle class, New England town. The film contains only one visible crane shot in which the camera scan over the fictional town of Stoningham, seen during the opening credits. Tracking and dollying shots are used frequently for interior shots.[7] The set was later featured on the television series Leave It to Beaver.

Reception

All That Heaven Allows was referred to as a “woman’s picture” in the film trade press and was specifically marketed towards women. The film press compared it favorably to Douglas Sirk's previous movie, Magnificent Obsession (1954), which had also starred Wyman and Hudson. A review in Motion Picture Daily was generally positive and praised Sirk for his stunning use of color and mise en scène: "In a print by Technicolor, the exterior shots and the interior settings are so beautifully photographed that they point up the action of the story with telling effect." Motion Picture Daily also reported that the film earned $16,000 its opening day and did “above average” business in areas like Atlanta, Miami, New Orleans and Jacksonville.

All That Heaven Allows was released in Great Britain on August 25, 1955, several months before its U.S. premiere. The film opened in Los Angeles on Christmas Day, 1955 and in New York City on February 28, 1956 following an extensive advertising campaign focusing on such popular women's magazines as McCall’s, Family Circle, Woman’s Day and Redbook.[8][9][10]

Although Sirk's reputation waned in the 1960s — as he was dismissed as a director of dated and insubstantial Hollywood melodramas — it revived the 1970s with the praise of New German Cinema directors such as Rainer Werner Fassbinder and the publication of Jon Holliday's Sirk on Sirk, in which the filmmaker describes his aesthetic and social perspective — often subversive.[11] His reputation, and that of All That Heaven Allows, has only grown since then, with critic Richard Brody describing him as a master of both melodrama and comedy, and the film as remarkable for its use of Henry David Thoreau's Walden as a homegrown American philosophy depicted as a "vital and ongoing experience."[12]

On Rotten Tomatoes, All That Heaven Allows has a rating of 93% based on 28 reviews, with an average rating of 7.7/10.[13]

Awards and honors

In 1995, All That Heaven Allows was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[14]

References in other films

All That Heaven Allows inspired Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974)[15] in which a mature woman falls in love with an Arab man. The Sirk film was spoofed by John Waters with his film Polyester ( 1981). Todd Haynes' Far from Heaven (2002) is an homage to Sirk's work, in particular All That Heaven Allows and Imitation of Life. François Ozon's 8 Women (8 Femmes, 2002) featured the winter scenes and the deer from the film.

See also

References

- ↑ All That Heaven Allows at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ↑ British Newspaper Archive

- ↑ 'The Top Box-Office Hits of 1956', Variety Weekly, January 2, 1957

- ↑ Laura Mulvey (18 June 2001). "All That Heaven Allows". Film Essays. The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ "All That Heaven Allows". TCM. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley. "Screen: Doleful Domestic Drama; Mayfair Offering 'All That Heaven Allows' Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson Teamed Again." Editorial. The New York Times [New York City] 29 Feb. 1956: n. pag. The New York Times. The New York Times. Web. 18 Nov. 2016.<https://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9506E5DB153CE03BBC4151DFB466838D649EDE>.

- ↑ Internet Movie Database. ""All That Heaven Allows" Filming Locations." IMDb. IMDb.com, n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2016. <https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0047811/locations?ref_=tt_dt_dt>.

- ↑ Media History Project. "Motion Picture Daily (Jan-Mar 1956)." Motion Picture Daily (Jan-Mar 1956). Media History Digital Library, n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2016. <https://archive.org/stream/motionpicturedai79unse#page/n425/mode/2up/search/%22All+That+Heaven+Allows%22>.

- ↑ Media History Project. "Motion Picture Daily (Oct-Dec 1955)." Motion Picture Daily (Oct-Dec 1955). Media History Digital Library, n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2016. <https://archive.org/stream/motionpicturedai78unse_0#page/n7/mode/2up>.

- ↑ Media History Project. "Motion Picture Daily (Jan-Mar 1955)." Motion Picture Daily (Jan-Mar 1955). Media History Digital Library, n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2016.<https://archive.org/stream/motionpicturedai77unse#page/n261/mode/2up>.

- ↑ Manuel Betancourt. "Douglas Sirk: From the Archives." Film Comment (December 22, 2015). Film Comment, n.d. Web. 22 Dec. 2015.<https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/sirk-from-the-archives/>.

- ↑ Richard Brody. "Douglas Sirk's Glorious Cinema of Outsiders." The New Yorker (December 21, 2015). The New Yorker, n.d. Web. 21 Dec. 2015.<https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/douglas-sirks-glorious-cinema-of-outsiders>.

- ↑ Rotten Tomatoes

- ↑ "National Film Registry" Archived 2013-03-28 at the Wayback Machine.. Library of Congress, accessed October 28, 2011.

- ↑ "All That Heaven Allows". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2016-01-25.

External links

- All That Heaven Allows on IMDb

- All That Heaven Allows at AllMovie

- All That Heaven Allows: An Articulate Screen an essay by Laura Mulvey at the Criterion Collection

- All That Heaven Allows Gary Morris DVD Review at Images Journal