Alfred Corning Clark

| Alfred Corning Clark | |

|---|---|

Clark circa 1893 | |

| Born |

November 14, 1844 Manhattan, New York City |

| Died |

April 8, 1896 (aged 51) Manhattan, New York City |

| Resting place | Hudson City Cemetery, Hudson, Columbia County, New York, USA |

Alfred Corning Clark I (November 14, 1844 – April 8, 1896) was an American philanthropist.[1][2]

Biography

He was the son of Edward Cabot Clark (1811–1882) and Caroline Jordan (1815–1874). His father made a fortune as the partner of Isaac Singer in the Singer Sewing Machine Company, invested it in Manhattan, New York City real estate, and left a $25,000,000 (approximately $633,966,000 today) estate at his death.[3] In 1869, Clark married Elizabeth Scriven (1848–1909), and they had four sons: Edward Severin Clark, Robert Sterling Clark, Frederick Ambrose Clark and Stephen Carlton Clark.

Clark maintained three residences in Manhattan: a city house at 7 West 22nd Street for his family, a nearby flat at 64 West 22nd Street for guests, and a large apartment in The Dakota overlooking Central Park for entertaining.[4] Clark's father built The Dakota (1880–84), but died during its construction. Edward Cabot Clark skipped a generation and bequeathed the building to his 12-year-old grandson and namesake, Edward Severin Clark.[5]

Clark assembled a collection of French academic paintings. He purchased Pollice Verso (Thumbs Down) (1872) by Jean-Léon Gerome from the estate of Alexander Turney Stewart.[6] It is now in the collection of the Phoenix Art Museum. In 1888, he purchased Gerome's The Snake Charmer (1880), but his family sold it after his death. His son Sterling re-acquired the painting in 1942 for the museum he founded, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.[7]

According to Debby Applegate's review in The New York Times Book Review of Nicholas Fox Weber's group biography, The Clarks of Cooperstown (2007):

Weber suggests that Alfred [Corning Clark] led a dual life: a quiet family man in America and a gay aesthete in Europe, especially in France, which he declared "the Mecca of brotherly feeling." He was a generous patron to male artists; for 19 years his closest companion was a Norwegian tenor named Lorentz Severin Skougaard. When his father's death forced him to return to Manhattan, Alfred installed Skougaard down the block from the town house where he lived with his wife and children. [Henry] James's shadow lingers longest in this chapter; surely this was the sort of thing he meant by those uneasy intimations that beneath Europe's splendor and refinement lurked something unspeakable. Weber's bluntness, by contrast, highlights how much of that beauty was created by gay men seeking warm communities of free expression.[8]

Clark met Severin Skougaard (1837–1885) in Paris in 1866, where the singer was studying.[9] In 1869 – the same year that he married Elizabeth Scriven – Clark began making annual summer visits to Norway, eventually building a house on an island near Skougaard's family home.[9] He gave his son Edward, born 1870, the middle name Severin. When in New York City, Skougaard occupied Clark's flat at 64 West 22nd Street.[4] During an 1885 visit, Skougaard was strickened with typhoid and died.[9] Clark eulogized him in a privately published biographical sketch,[10] and created a $64,000 endowment in his memory for Manhattan's Norwegian Hospital, 4th Avenue & 46th Street.[11] Clark also commissioned Brotherly Love (1886–87) by American sculptor George Grey Barnard to adorn his friend's grave in Langesund, Norway.[12] The homoerotic sculpture depicts two nude male figures blindly reaching out to each other through the block of marble that separates them.[13]

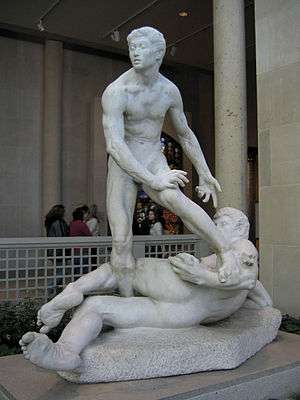

Clark became Barnard's patron, commissioning works and providing financial support to him in Paris.[9] Clark paid Barnard $25,000 to carve a marble version of his Struggle of the Two Natures in Man (1888), which was completed in April 1894.[14] Barnard exhibited the piece at the 1894 Paris Salon, where the jury, headed by Auguste Rodin, pronounced it a work "of superlative merit."[14] Clark brought the larger-than-life-sized sculpture to New York City. Soon after his death, Clark's widow donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[14]

Clark died of pneumonia on April 8, 1896 in Manhattan, New York City.[1]

Legacy

Following more than six years as a widow, in 1902 Elizabeth Scriven Clark became the second wife of Henry Codman Potter, the Episcopal bishop of New York.[15]

Philanthropy

Clark's donation of $50,000 to the piano prodigy Jozef Hofmann in 1887 spared the eleven-year-old from having to complete a fifty-recital American tour that had been criticized by Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.[16] With this financial security, Hofmann and his family returned to Europe where the boy could receive a broader education before resuming his concert career.[16] In addition to becoming one of history's most outstanding piano virtuosi, Hofmann's study in science and mathematics enabled him to become an inventor in later life, earning over 70 patents.[17]

Between 1888 and 1891, Clark built the first gymnasium in Cooperstown, New York.[18] Although it remained popular, by the 1920s the facility had become obsolete and was demolished and rebuilt by his son Edward Severin Clark. A new Alfred Corning Clark Gymnasium opened in 1930, and featured such improvements as a swimming pool and bowling alleys. The current successor to the 1930 ACC Gym is the Clark Sports Center a greatly expanded facility, completed in the mid-1980s, located on the former grounds of Iroquois Farm (the F. Ambrose Clark estate) under the direction of Stephen Carlton Clark, Jr., the great-grandson of the gym's founder.[19]

Clark donated works to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, including Madame Gaye (1865) by Marià Fortuny.[20]

Legacy

Artworks once owned by Alfred Corning Clark

Madame Gaye (1865) by Marià Fortuny, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Madame Gaye (1865) by Marià Fortuny, Metropolitan Museum of Art Court of the Alhambra (1871), Museu Fundacio Gala-Salvador Dalí

Court of the Alhambra (1871), Museu Fundacio Gala-Salvador Dalí Pollice Verso (1872) by Jean-Léon Gerome, Phoenix Art Museum

Pollice Verso (1872) by Jean-Léon Gerome, Phoenix Art Museum The Snake Charmer (1880) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, Clark Art Institute

The Snake Charmer (1880) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, Clark Art Institute Struggle of the Two Natures in Man (1892–94) by George Grey Barnard, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Struggle of the Two Natures in Man (1892–94) by George Grey Barnard, Metropolitan Museum of Art The Ameya (1893) by Robert Frederick Blum, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Ameya (1893) by Robert Frederick Blum, Metropolitan Museum of Art

References

- 1 2 "Alfred Corning Clark" (PDF). The New York Times. April 12, 1896.

- ↑ Portrait of Alfred Corning Clark by William Jacob Baer, from Clark Art Institute.

- ↑ Jack Buckman, Unraveling the Threads: The Life, Death and Resurrection of the Singer Sewing Machine Company, America's First Multi-National Corporation (Dog Ear Publishing, 2016).

- 1 2 Weber, p. 76.

- ↑ Stephen Birmingham, Life at The Dakota: New York's Most Unusual Address, (Open Road Media, 2015).

- ↑ Weber, p. 83.

- ↑ Jori Finkel, "Jean-Léon Gérôme's 'The Snake Charmer': A Twisted History," The Los Angeles Times, June 13, 2010.

- ↑ Debby Applegate, "Outrageous Fortune," The New York Times Book Review, May 20, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Harold E. Dickson, "Barnard and Norway," The Art Bulletin, vol. 44, no. 1 (March 1962), pp. 55-59.(JSTOR) $

- ↑ Alfred Corning Clark, Lorentz Severin Skougaard: a sketch, mainly autobiographic, (privately published, 1885), from WorldCat.

- ↑ The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 26, 1911, p. 1.

- ↑ Glenn C. Altschuler, "Meet 3 Generations of American Originals," The Baltimore Sun, June 17, 2007.

- ↑ "George Grey Barnard (1863 – 1938)," in Lauretta Dimmick and Donna J. Hassler. American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A catalogue of works by artists born before 1865. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999. pp. 421-27.

- 1 2 3 "190: Struggle of the Two Natures of Man, 1888," American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A catalogue of works by artists born before 1865, (MMA, 1999), pp. 421-23.

- ↑ Weber, pp. 104-105.

- 1 2 Harold C. Schonberg, The Great Pianists from Mozart to the Present, 2nd ed., Simon & Schuster, 1987

- ↑ Aubrey D. McFadyen, "Invention—Hobby of Great Men," Popular Science, January 1928, p. 136.

- ↑ Alfred Corning Clark Gymnasium, Copperstown, N.Y. from Postcards of the Past.

- ↑ Mark Simonson, "Clark family helped keep public in shape with gyms," The Daily Star (Oneonta, New York).

- ↑ Madame Gaye - Provenance, from Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Alfred Corning Clark II, from Find-a-Grave.

- ↑ Brotherly Love (opera) Archived 2017-02-23 at the Wayback Machine.

Sources

- Nicholas Fox Weber, The Clarks of Cooperstown: Their Singer Sewing Machine Fortune, Their Great and Influential Art Collections, Their Forty-year Feud. Alfred A. Knopf, 2007. ISBN 0307263479