Alfonso de Portago

| |

| Born | 11 October 1928 |

|---|---|

| Died | 12 May 1957 (aged 28) |

| Formula One World Championship career | |

| Nationality |

|

| Active years | 1956 – 1957 |

| Teams | Ferrari |

| Entries | 5 |

| Championships | 0 |

| Wins | 0 |

| Podiums | 1 |

| Career points | 4 |

| Pole positions | 0 |

| Fastest laps | 0 |

| First entry | 1956 French Grand Prix |

| Last entry | 1957 Argentine Grand Prix |

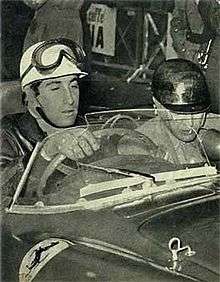

Alfonso Antonio Vicente Eduardo Angel Blas Francisco de Borja Cabeza de Vaca y Leighton, 11th Marquess of Portago (11 October 1928 – 12 May 1957), best known as Alfonso de Portago, was a Spanish aristocrat, racing driver and bobsleigh driver.

Biography

Early life

Born in London, he was educated at Biarritz,[1] in France.[2] He became articulate in four languages. Portago was heir to one of the most respected titles in Spain[3] and a millionaire.[2] Among his ancestors were an explorer (Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca), a Governor of Madrid, and a war hero. His Spanish father was Antonio Cabeza de Vaca. He died during half time at a polo match at a young age. His mother was named Olga Leighton and was an Irish nurse. She also had a daughter named Sol, for Soledad, who married and became known as the Marquise de Moratalla in racing circles. She died in 2017.[4] Olga's first husband, Francis John Mackey, was more than 40 years older than she was. He shot himself while terminally ill and left Olga an enormous fortune made as founder of Household Finance Corp.[5]

Portago was 1.83 m tall and weighed 77 kg.[3] De Portago won a bet at the age of 17 when he flew his plane beneath a bridge. He participated twice in the Grand National Steeplechase at Aintree as a gentleman jockey, although he found keeping his weight down to be a struggle.[3]

Race car driver

de Portago began racing sports cars in 1953 after his meeting with the Ferrari importer in the USA, Luigi Chinetti, who asked him to be his co-driver in the Carrera Panamericana.[1] He later raced alone in a personal Ferrari Sport model at the 1954 1000 km Buenos Aires.[1] de Portago won six major races, including the Tour de France automobile race, the Grand Prix of Oporto, and the Nassau Governor's Cup (twice). In Nassau, during the winter of 1956, Portago trailed the car ahead of him by centimeters while travelling at 240 km/h. Portago used his skill to avert careening into a crowd after the driver ahead of him touched his brakes and both cars went into a 180 m skid. Among sports car enthusiasts, de Portago was known as a two-car man, because of the many burned-out brakes, clutches, transmissions, and wrecked cars for which he was responsible. He often needed several cars to finish a race.[3]

He participated in 5 World Championship Formula One Grands Prix, debuting on 1 July 1956. His best result was a second place at the 1956 British Grand Prix (a shared drive with Peter Collins), and scored a total of four championship points. In 1953 he raced with Luigi Chinetti in the Carrera Panamericana. During the 1955 British Grand Prix at Silverstone, Portago was thrown from his Ferrari while racing at 140 km/h after losing control on a patch of oil. He was hospitalized with a broken leg.[3]

Bobsleigh

| Medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bobsleigh | ||

| Representing | ||

| World Championships | ||

| 1957 St. Moritz | Two-man | |

He also was a bobsleigh runner, recruiting several cousins in order to form Spain's first bobsleigh team for the 1956 Winter Olympic Games in Cortina d'Ampezzo.[6] He had had only two or three practice runs in Switzerland before buying a pair of sleds. With de Portago steering, the two-man bob finished fourth to the surprise of the traditional teams, missing out on a medal by 0.16 seconds.[6] He was introduced to bobsledding by an American from Beloit, Wisconsin, Edmund Nelson, whom he later teamed up with in order to win the Tour de France automobile race.

Portago also won a bronze medal in the two-man event at the 1957 FIBT World Championships in St. Moritz.

Death

He and his co-driver Edmund Nelson were killed on 12 May 1957[7] in a crash during that year's Mille Miglia, in a straight road section between Cerlongo and Guidizzolo, in the communal territory of Cavriana[1] about 70 km from Brescia, the start and finish point of the event race. The wreck also claimed the lives of nine spectators, among them five children.[1] Portago was apprehensive about competing in the Mille Miglia, a race he considered too dangerous to be run, as he was concerned about the almost complete impossibility about knowing every corner (even with a navigator) and every possible road condition over 1,000 mi (1,600 km) of open public roads with very limited information on what to expect in the race. A tire blew on Portago's third-place[7][8] Ferrari 335 S causing it to spin into the crowd lining the highway. He was travelling at 240 km/h (150 mph) when the tire went flat. The 335 hurtled over a canal on the left side of the road, then veered back across the canal, causing the deaths of nine onlookers in total. Two of the dead children were hit by a concrete highway milestone that was ripped from the ground by Portago's car and thrown into the crowd. The bodies of Portago and Nelson were badly disfigured beneath the Ferrari, which was upside down. Portago's body was in two sections.[2]

As T.C. Browne wrote, "The inevitable happened when Alfonso [...] de Portago stopped alongside the course, ran to the fence, kissed Linda Christian, ran back to his Ferrari and drove on to his destiny, killing himself, his co-driver, 10 spectators, and the Mille Miglia".[9]

Once Portago commented, "I won't die in an accident. I'll die of old age or be executed in some gross miscarriage of justice". Nelson countered this assertion, saying de Portago would not live to be 30. According to Nelson, "every time Portago comes in from a race the front of his car is wrinkled where he has been nudging people out of the way at 130 mph (210 km/h)".[3]

Legacy

The Portago curve at the St. Moritz-Celerina Olympic Bobrun is named in his honor for his foundation's efforts to renovate the lower portion of the track. A Portago curve (#7) is also shown on the Jarama motor racing circuit in Spain.

Personal life

In 1949, when he was only twenty, de Portago married American former model Carroll McDaniel (by whom he had two children). McDaniel was several years older than de Portago and they barely knew each other. She subsequently married the philanthropist Milton Petrie. One of de Portago's daughters is photographer Andrea Portago, who was on the June 1977 cover of Andy Warhol's Interview magazine. His son, Anthony, was a stockbroker born around 1954. He married in 1973 (and divorced in 1978) Sorbonne-educated society fundraiser and costume- and set-designer Barbara, daughter of German nobleman Henrik von Schlubach. Her stepfather, Gerald van der Kemp, was a curator who restored the Palace of Versailles.[10][11][12] Barbara de Portago subsequently married, in 1984, actor and playwright Jason Harrison Grant,[13] and, after their divorce, married in 1991 (divorced 1994) investment banker William James Tapert.[14][15][16]

Supposedly, Carroll McDaniel and Alfonso de Portago were in the process of getting a divorce so he could legitimize his invalid Mexican marriage to fashion model Dorian Leigh (who had already aborted their first baby in 1954 and then gave birth to their son Kim on 27 September 1955). Leigh was eleven years his senior.[17] However, de Portago was also dating actress Linda Christian, actor Tyrone Power's ex-wife.

Complete Formula One World Championship results

(key)

| Year | Entrant | Chassis | Engine | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | WDC | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari D50 | Ferrari V8 | ARG | MON | 500 | BEL | FRA Ret |

GBR 2 † |

GER Ret |

ITA Ret |

15th | 3 |

| 1957 | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari D50A | Ferrari V8 | ARG 5 * |

MON | 500 | FRA | GBR | GER | PES | ITA | 20th | 1 |

- † Indicates Shared Drive with Peter Collins

- * Indicates Shared Drive with José Froilán González

Titles and styles

Titles

- 11th Marquess of Portago

- 13th Count of the Mejorada

Styles

- 11 October 1928 – 1942: The Most Excellent Don Alfonso Antonio Vicente Eduardo Ángel Blas Francisco de Borja Cabeza de Vaca y Leighton

- 1942 – 12 May 1957: The Most Excellent The Marquess of Portago and Count of the Mejorada

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Alfonso Antonio Vicente Eduardo Angel Blas Francisco de Borja Cabeza de Vaca y Leighton, marchese di Portago". Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Daredevil Sportsman Perishes", Los Angeles Times, May 13, 1957, Page 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Marquis at the Wheel", The New York Times, March 17, 1957, Page SM40.

- ↑ "Marquesa de Moratalla, owner of Gold Cup hero The Fellow, dies aged 87". Racing Post.

- ↑ Leigh, Dorian. The Girl Who Had Everything. p. 94. ISBN 9780385143318.

- 1 2 Viva F1. "Formula One at the Olympics". Archived from the original on 2012-08-08. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- 1 2 Forix (retrieved 24 October 2012)

- ↑ Or fourth-place, media did not make it clear at the time Forix (retrieved 24 October 2012)

- ↑ The road races, Motor Trend 100 Years of the Automobile, 1985, ISBN 0-8227-5092-9, p. 233.

- ↑ Wicker, Tom (28 December 1979). "Barbara de Portago, 'a Real Doer' With a Flair for Parties". Retrieved 9 April 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- ↑ "After Growing Up at Versailles, Barbara De Portago Has Become the Sun Queen of New York Society". people.com. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul (9 April 2018). "Gerald Van der Kemp, 89, Versailles' Restorer". Retrieved 9 April 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- ↑ "Barbara de Portago Wed to J. H. Grant". nytimes.com. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ "Barbara de Portago, Consultant, Wed". nytimes.com. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ Staff, WWD (19 October 1994). "Article October 19, 1994". wwd.com. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ Yazigi, Monique P. (27 June 1999). "Not Just Another Working Girl". Retrieved 9 April 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- ↑ Leigh, Dorian. The Girl Who Had Everything, pp. 113–114, 128.

Sources

- Wallechinsky, David (1984). "Bobsled: Two-man". The Complete Book of the Olympics: 1896 – 1980. New York: Penguin Books. p. 558.

- Dolcini, Carlo. Alfonso de Portago. L'ultima corsa. Silea. ISBN 978-88-7911-532-2.