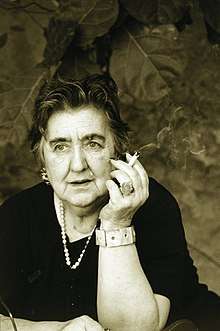

Alda Merini

| Alda Merini | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

March 21, 1931 Milan, Italy |

| Died |

November 1, 2009 (aged 78) Milan, Italy |

| Resting place | Monumental Cemetery of Milan |

| Occupation | writer, poet |

| Language | Italian |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Notable awards | Viareggio Prize, Premio Dessì |

| Years active | 1953–2008 |

Alda Merini (Milan, 21 March 1931 – Milan, 1 November 2009) was an Italian writer and poet. Merini was quite young when, as a poet, she gained the attention and the admiration of other Italian writers, such as Giorgio Manganelli, Salvatore Quasimodo and Pier Paolo Pasolini. Her writing style is described as intense, passionate and mystic, and it bears an influence from Rainer Maria Rilke.

Some of her poems concern her time in a mental home (1964 to the late 1970s) and are often of a long and dramatic nature. She explores the "otherness" of madness as part of creative expression. The poem "The other truth. Diary of a dropout" (L'altra verità. Diario di una diversa) is considered by some as her masterpiece, Scheiwiller, 1986.

In 1996 she was nominated by the "Académie Francaise" as candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In 2007 she won the Elsa Morante Ragazzi Award with Alda e Io – Favole written in cooperation with the fable writer Sabatino Scia. Giorgio Napolitano then President of the Italian Republic described her, at her death, as an "inspired and limpid poetic voice."

Biography and Works

Alda Giuseppina Angela Merini was born on March 21, 1931, in viale Papiniano 57, Milan[1] in a family of modest means. The father, Nemo Merini, was an employee working at the insurance company "Vecchia Mutua Grandine ed Eguaglianza il Duomo". The mother, Emilia Painelli, was a housewife. Alda was the second daughter of three children, including Anna, born on November 26, 1926, and Ezio, born in January 1943, who appear, albeit with a certain detachment, in her poems. Known about her childhood is only the little she wrote in the short autobiographical notes on the occasion of her second edition of the Spagnoletti Anthology: "a sensitive girl, with a rather melancholic character, quite excluded and little understood by her parents but very good at her classes in primary school ... because studying has always been a vital part of my life".[2]

After finishing the primary cycle with very high grades, she attended the three-year school-to-work transition programme at the Istituto "Laura Solera Mantegazza" in via Ariberto in Milano, trying in the meantime to be admitted to Liceo Manzoni. However, she did not succeed, as she did not pass the Italian language test. In the same period she also studied the piano, an instrument she especially loved. She made her authorial debut at the age of fifteen, under the guidance of Giacinto Spagnoletti, who discovered her artistic talent.[3] In 1947, Merini met " the first shadows of her mind"[4] and was interned for a month in the clinic Villa Turro in Milano. When she left the clinic, some friends got particularly close to her and Giorgio Manganelli, whom she met at the house of Spagnoletti together with Luciano Erba and David Maria Turoldo, sent her to the psychoanalysts Fornari and Musatti.

Giacinto Spagnoletti was the first to publish her work, in Antologia della poesia italiana contemporanea 1909–1949, published in 1950. The chosen works were the lyric poems Il gobbo, dated 22 December 1948, and Luce, dated 22 December 1949, dedicated to Giacinto Spagnoletti. In 1951, at the suggestion of Eugenio Montale and Maria Luisa Spaziani, the editor Giovanni Scheiwiller published two of the author's previously unpublished poems in Poetesse del Novecento. From 1950 to 1953, the writer developed a professional connection and a close friendship with Salvatore Quasimodo. At the end of the relationship with Giorgio Manganelli, August 9, 1953 she married Ettore Carniti, a bakery owner from Milan. The same year Schwarz publishing house published her first volume of poems entitled La presenza di Orfeo. In 1955 her second collection of poems was published, Paura di Dio , that included the poems written between 1947 and 1953, after which followed Nozze romane and, in the same year, Bompiani published the work in prose La pazza della porta accanto.[5]

In the same year, her first daughter, Emanuela, was born, and the writer dedicated to Pietro De Pascale, the doctor who took care of her child, the collection of poems Tu sei Pietro, published in 1962 by Scheiwiller. AfterTu sei Pietro was the beginning of a period of isolation and silence for the author, due to her internment in the clinic "Paolo Pini", which lasted until 1972, albeit with sporadic visits home during which other three daughters were born.[6] A time split between periods of health and illness followed, probably caused by her bipolar disorder. In 2007 with Alda e Io – Favole, written in collaboration with the fable writer Sabatino Scia, she won the Elsa Morante Ragazzi prize. The 17 October 2007 the poet obtained a degree honoris causa in "Teorie della comunicazione e dei linguaggi" at the School of Education Sciences at the University of Messina, giving lectio magistralis on the meandering twists and turns of events that constituted her life.

La terra santa

In 1979 Merini began her most intense works on her dramatic and upsetting experience at the psychiatric hospital. These works were included in what Maria Corti called "her masterpiece", la Terra Santa, thanks to which 1993 she won the Librex Montale Prize.[7] On July 7, 1983, her husband died and Alda,without any support from the literary world, fruitlessly tried to spread her poems. Maria Corti asserts that Merini attempted to have her works published by some of the most important Italian editors too, but without any success.[8] However, in 1982, Paolo Mauri[9] offered to have thirty of her poems, chosen from a typewritten document of about 100 texts, to be published on his journal (n. 4, Winter 1982-Spring 1983). Shortly after that, together with the publisher Scheiwiller, other ten poems were added and, in 1984, La Terra Santa was finally issued.

During that time Merini rented a room in her house to the painter Charles and started being in touch with the poet Michele Pierri that, in that difficult period of recreating bonds with the literary world, showed to value her poems. In October 1983 Alda and Michele got married and went to live in Taranto. In the time following her wedding she wrote twenty poems-portraits of La gazza ladra, probably dating back to 1985 and unreleased until the volume Vuoto d'amore, together with some works for Pierri. It is still in Taranto that she finished L'altra verità. Diario di una diversa.

L'altra verità. Diario di una diversa

Non avrei potuto scrivere in quel momento nulla che riguardasse i fiori perché io stessa ero diventata un fiore, io stessa avevo un gambo e una linfa (English: I couldn't have written anything about the flowers in that moment because I myself had become a flower, I myself had a stem and I myself produced sap.)

- Alda Merini, from L'altra verità. Diario di una diversa

In July 1986, after a new period in the psychiatric hospital in Taranto, she went back to Milan and started a therapy with the doctor Marcella Rizzo, to whom she dedicated more than a poem. In the same year she started writing again and got newly in touch with old friends such as Vanni Scheiwiller, who published "L'altra verità. Diario di una diversa",her first book written in prose that, as Giorgio Manganelli stated in the preface, "it is neither a document nor a testimony on the ten years spent by the writer in a mental institution. It is a 'reconnaissance' through epiphanies,deliria, tunes, songs, revelations and apparitions, of a space -not a place- where, failing every habit and everyday perspicacity, the natural hell and the numinuous nature of human being burts out."[10] To this, it followed Fogli bianchi in 1987, La volpe e il sipario (1997) and Testamento (1988). In 1987 she was a finalist for the literary prize Premio Bergamo.

Caffè sui Navigli

These were for Merini very productive years from a literary point of view. During the winter of 1989 the poet spent time at the coffee-bookshop Chimera, not far from where she lived, and offers her typrewritten poems to her friends. In this period books like Delirio amoroso (1989) and Il tormento delle figure (1990) were born. In the following years different publications reinforce her comeback on the literary scene. In 1991 Le parole di Alda Merini and Vuoto d'amore are published, followed by Ipotenusa d'amore in 1992. In 1993 there are other three publications: La palude di Manganelli or il monarca del re, the volume Aforismi, with photographs by Giuliano Grittini, and Titano amori intorno . In this year she was endowed the Premio Librex Montale for poetry. This prize officially put the poet in the circle of great contemporary intellectuals and conferred on her the same literary status of writers such as Giorgio Caproni, Attilio Bertolucci, Mario Luzi, Andrea Zanzotto, and Franco Fortini.[11]

Reato di Vita

In 1994, Merini's volume of poetry Sogno e Poesia (Dream and Poetry) saw the light of day, with an edition including twenty engravings by various contemporary artists. In 1995 Bompiani published La Pazza della porta accanto (The Crazy Woman Next Door) and Einaudi published Ballate non pagate (Unpaid Dances). The Apulian musician Vincenzo Mastropirro set to music some lyrics taken from Ballate. Still in 1994 Reato di vita (Crime of Life) was released by Edizioni Melusine, subtitled Autobiography & Poetry. In 1996, with the volume La Vita Facile, she received the Viareggio Prize, and in 1997, the Procida Prize.

Also in 1996 was the publication of a small book of poems edited by La Vita Felice entitled Un'anima indocile (A Restless Soul), composed of both old and new poems, of a confessional diary, of brief stories, and of an interview done with the author. In the same year Merini met the Bergamo artist Giovanni Bonaldi with whom she formed a genuine and strong friendship. They began to collaborate on a publication. In 1997, Girardi published the collection of poems La volpe e il sipario (The Fox and the Curtain) with illustrations by Gianni Casari. In this collection it becomes more than ever apparent the technical finesse of spontaneous oral poetry that others have transcribed.

This was a phenomenon, that, "even being ostensibly contemporary, this choice of oral transmission over written, is for now unique in the universe of contemporary poetry." [13]. The oral nature of Merini's poetry at this time led to ever briefer texts, and, in the end, to aphorisms. In November of the same year, Ariete published Curva di fuga [14] (The Vanishing Curve), which Alda Merini presented at the Castello Sforzesco at Soncino, where they presented the Milanese poet with honorary citizenship. Still in 1997 Bonaldi drew five illustrations for a collection of poems and epigrams of Merini entitled Salmi della gelosia (Psalms of Jealousy), printed by Ariete.

Alda Merini, a woman on stage

In 2009, the documentary Alda Merini, una donna sul palcoscenico (Alda Merini, a woman on stage), from the director Cosimo Damiano Damato, was presented at Authors' Day at the 66th Venice Film Festival. The film, produced by Angelo Tumminelli for Star Dust International, included portions of Merini's text read by Mariangela Melato, and was filmed by Giuliano Grittini. The poet and director became great friends during the filming and Merini gave him unpublished poems to include in the film. Merini wrote a poem, "Una donna sul palcoscenico," specifically for the purpose of including it in Damato's film:

One day I lost words/ I came here to tell you this and not because you responded/ I don't love conversations or questions: I noticed that I once sang in a voiceless choir/ I meditated a long time on the silence, and to silence there is no response./ I threw away my poems/ I didn't have paper to write them on./ Then I noticed that strange animals like ancestral beasts in the form of men from asylums were coming close to me/ some of them helped me feel unique, looked at me. / For them, I thought, there were no stoplights, buildings, streets./ This ramshackle place, my mind has found solitude./ Then a saint with something to give arrived/ a saint that was not chained, that was not an evildoer,/ the one thing that I had had during all these years./ I would have followed him / but I forgot how to fall in love./ He came, a saint that illuminated me like a star./ A saint responded to me: why don't you love yourself? My indolence was born./ I no longer see people that hit me, and I no longer visit the nuthouse./ I have died in indolence.

"And with a voice that betrays her childlike candor," wrote Roberta Bottari on Il Messagero, "a smile that illuminates her eyes and the unmistakable fire-red lipstick, Alda Merini abandoned herself to Cosimo Damato. She trusts him, she 'feels' that she will not be betrayed. And while the director stands with the still camera, waiting for a look, a twitch, a word from the woman, she seduces him speaking of poetry, mysticism, philosophy, music, of foolishness poured out in verse, of Christ and passion, without censuring family pain and the experience of the asylum."

Poems to music

- 2004: Milva canta Merini, album of Italian singer Milva. Music by Giovanni Nuti.

- 2015: Dio, composition by Francesco Trocchia for female choir and piano; lyrics by Alda Merini (from Francesco 2007)

References

- ↑ "Archivio Corriere della Sera". archiviostorico.corriere.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ↑ Spagnoletti, Giacinto (ed.) (1959). Poesia italiana contemporanea, 1909–1959. Parma: Guanda.

- ↑ "Corriere della Sera".

- ↑ Maria Corti in Introduzione di Vuoto d'amore, Einaudi, Torino, 1991, p.VI

- ↑ "Alda Merini". Wikipedia. 8 February 2017.

- ↑ from Maria Corti in op. cit., pag. VIII

- ↑ Maria Corti in Introduzione a Alda Merini, Fiore di poesia, 1951–1997, Einaudi, Torino, p.XI

- ↑ Maria Corti in op. cit., p.XII

- ↑ At the time director of the journal Il cavallo di Troia

- ↑ Giorgio Manganelli in Introduzione a Alda Merini. L'altra verità, diario di una diversa. Rizzoli, 1997, p.7.

- ↑ "Alda Merini". Wikipedia. 8 February 2017.

External links

- Official website

- Alda Merini site at the Wayback Machine (archived July 13, 2004)

- MEMORIAL

- unafavolaperprotesta.com