Ad blocking

| Part of a series on |

| Internet marketing |

|---|

| Search engine marketing |

| Display advertising |

| Affiliate marketing |

| Mobile advertising |

Ad blocking or ad filtering is a type of software that can remove or alter advertising content from a webpage, website, or a mobile app. Ad blockers are available for a range of computer platforms, including desktop and laptop computers, tablet computers and smartphones. A variety of methods have been used for blocking advertisements.[1] The benefits of this software are wide-ranging and the use of ad blocking software is increasing.[2] However, many media owners (publishers) rely on advertising to fund the content that they provide to users.[3] Some publishers, like Forbes, have taken counter-measures against users who block ads on the sites they visit.[4]

Technologies and native countermeasures

Online advertising exists in a variety of forms, including web banners, pictures, animations, embedded audio and video, text, or pop-up windows, and can employ audio and video autoplay. All browsers offer some ways to remove or alter advertisements: either by targeting technologies that are used to deliver ads (such as embedded content delivered through browser plug-ins or via HTML5), targeting URLs that are the source of ads, or targeting behaviors characteristic to ads (such as the use of HTML5 autoplay of both audio and video).

Reasons for blocking ads

From the standpoint of an Internet user, there are various fundamental reasons why one would want to use ad blocking, in addition to not being manipulated by brands:

- Protecting their privacy

- Reduces the number of HTTP cookies

- Protecting themselves from malvertising

- Save bandwidth (and money)

- Better user experience

- Less cluttered pages

- Faster page loading times

- Fewer distractions

- Ergonomic reasons

- Animations is some ads are distracting to the point of making the site unusable

- The motion in some ads is nauseating for some users

- Save battery on mobile devices

- Prevent undesirable websites from making ad revenue out of the user's visit

Publishers and their representative trade bodies, on the other hand, argue that Internet ads provide revenue to website owners, which enable the website owners to create or otherwise purchase content for the website. Publishers claim that the prevalent use of ad blocking software and devices could adversely affect website owner revenue and thus in turn lower the availability of free content on websites.

Benefits

To users, the benefits of ad blocking software include quicker loading and cleaner looking web pages with fewer distractions,[5] lower resource waste (bandwidth, CPU, memory, etc.), and privacy benefits [6] gained through the exclusion of the tracking and profiling systems of ad delivery platforms. Blocking ads can also save substantial amounts of electrical energy and lower users' power bills.[7][8]

User experience

Ad blocking software may have other benefits to users' quality of life, as it decreases Internet users' exposure to advertising and marketing industries, which promote the purchase of numerous consumer products and services that are potentially harmful or unhealthy[9][10] and on creating the urge to buy immediately.[11] [12] The average person sees more than 5000 advertisements daily, many of which are from online sources.[13] Each ad promises viewers that their lives will be improved by purchasing the item that is being promoted[14][15][16] (e.g., fast food, soft drinks, candy, expensive consumer electronics) or encourages users to get into debt or gamble.[17] Additionally, if Internet users buy all of these items, the packaging and the containers (in the case of candy and soda pop) end up being disposed of, leading to negative environmental impacts of waste disposal. Advertisements are very carefully crafted to target weaknesses in human psychology;[9][18] as such, a reduction in exposure to advertisements could be beneficial for users' quality of life.

Unwanted advertising can also harm the advertisers themselves, if users become annoyed by the ads. Irritated users might make a conscious effort to avoid the goods and services of firms which are using annoying "pop-up" ads which block the Internet content the user is trying to view.[19] For users not interested in making purchases, the blocking of ads can also save time. Any ad that appears on a website exerts a toll on the user's "attention budget", since each ad enters the user's field of view and must either be consciously ignored or closed, or dealt with in some other way. A user who is strongly focused on reading solely the content that they are seeking, likely has no desire to be diverted by advertisements that seek to sell unneeded or unwanted goods and services.[19] In contrast, users who are actively seeking items to purchase, might appreciate advertising, in particular targeted ads.[20]

Security

Another important aspect is improving security; online advertising subjects users to a higher risk of infecting their devices with computer viruses than surfing pornography sites.[21] In a high-profile case, malware was distributed through advertisements provided to YouTube by a malicious customer of Google's Doubleclick.[22][23] In August 2015, a 0-day exploit in the Firefox browser was discovered in an advertisement on a website.[24] When Forbes required users to disable ad blocking before viewing their website, those users were immediately served with pop-under malware.[25] The Australian Signals Directorate recommends individuals and organizations block advertisements to improve their information security posture and mitigate potential malvertising attacks and machine compromise.[26] The information security firm Webroot also note employing ad blockers provide effective countermeasures against malvertising campaigns for less technically-sophisticated computer users.[27]

Monetary

Ad blocking can also save money for the user. If a user's personal time is worth one dollar per minute, and if unsolicited advertising adds an extra minute to the time that the user requires for reading the webpage (i.e. the user must manually identify the ads as ads, and then click to close them, or use other techniques to either deal with them, all of which tax the user's intellectual focus in some way),[28] then the user has effectively lost one dollar of time in order to deal with ads that might generate a few fractional pennies of display-ad revenue for the website owner. The problem of lost time can rapidly spiral out of control if malware accompanies the ads.[29][30]

Ad blocking also reduces page load time and saves bandwidth for the users. Users who pay for total transferred bandwidth ("capped" or pay-for-usage connections) including most mobile users worldwide, have a direct financial benefit from filtering an ad before it is loaded. Analysis of the 200 most popular news sites (as ranked by Alexa) in 2015 showed that Mozilla Firefox Tracking Protection lead to 39% reduction in data usage and 44% median reduction in page load time.[31] According to research performed by The New York Times, ad blockers reduced data consumption and sped up load time by more than half on 50 news sites, including their own. Journalists concluded that "visiting the home page of Boston.com (the site with most ad data in the study) every day for a month would cost the equivalent of about $9.50 in data usage just for the ads".[32] Streaming audio and video, even if they are not presented to the user interface, can rapidly consume gigabytes of transfer especially on a faster 4G connection. Even fixed connections are often subject to usage limits, especially the faster connections (100Mbit/s and up) which can quickly saturate a network if filled by streaming media. It is a known problem with most web browsers, including Firefox, that restoring sessions often plays multiple embedded ads at once.[33]

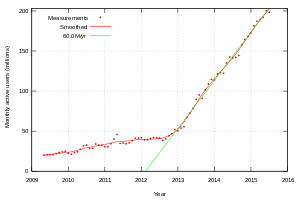

Popularity

Use of mobile and desktop ad blocking software designed to remove traditional advertising grew by 41% worldwide and by 48% in the U.S. between Q2 2014 and Q2 2015.[34] As of Q2 2015, 45 million Americans were using ad blockers.[34] In a survey research study released Q2 2016, MetaFacts reported 72 million Americans, 12.8 million adults in the UK, and 13.2 million adults in France were using ad blockers on their PCs, smartphones, or tablet computers. In March 2016, the Internet Advertising Bureau reported that UK adblocking was already at 22% among people over 18 years old.[35][36]

Methods

One method of filtering is simply to block (or prevent autoplay of) Flash animation or image loading or Windows audio and video files. This can be done in most browsers easily and also improves security and privacy. This crude technological method is refined by numerous browser extensions. Every Internet browser handles this task differently, but, in general, one alters the options, preferences or application extensions to filter specific media types. An additional add-on is usually required to differentiate between ads and non-ads using the same technology, or between wanted and unwanted ads or behaviors. The more advanced ad blocking filter software allow fine-grained control of advertisements through features such as blacklists, whitelists, and regular expression filters. Certain security features also have the effect of disabling some ads. Some antivirus software can act as an ad blocker. Filtering by intermediaries such as ISP providers or national governments is increasingly common.

Browser integration

As of 2015, many web browsers block unsolicited pop-up ads automatically. Current versions of Konqueror[37] and Internet Explorer[38] also include content filtering support. Content filtering can be added to Firefox, Chromium-based browsers, Opera, Safari and other browsers with extensions such as AdBlock, Adblock Plus and uBlock Origin, and a number of sources provide regularly updated filter lists. Adblock Plus (provided by the German software house Eyeo GmbH) is included in the freeware browser Maxthon from the People's Republic of China by default.[39] Another method for filtering advertisements uses Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) rules to hide specific HTML and XHTML elements. At the beginning of 2018, Google confirmed that the built-in ad blocker for the Chrome/Chromium browsers would go live on the 15th of February[40]: this ad blocker only blocks certain ads as specified by the Better Ads Standard[41] (defined by the Coalition for Better Ads®, in which Google itself is a board member[42]). This built-in ad blocking mechanism is disputed because it could unfairly benefit Google's advertising itself[43].

External programs

A number of external software applications offer ad filtering as a primary or additional feature. A traditional solution is to customize an HTTP proxy (or web proxy) to filter content. These programs work by caching and filtering content before it is displayed in a user's browser. This provides an opportunity to remove not only ads but also content which may be offensive, inappropriate, or even malicious (Drive-by download). Popular proxy software which blocks content effectively include Netnanny, Privoxy, Squid, and some content-control software. The main advantage of the method is freedom from implementation limitations (browser, working techniques) and centralization of control (the proxy can be used by many users). Proxies are very good at filtering ads, but they have several limitations compared to browser based solutions. For proxies, it is difficult to filter Transport Layer Security (SSL) (https://) traffic and full webpage context is not available to the filter. As well, proxies find it difficult to filter JavaScript-generated ad content.

Hosts file and DNS manipulation

Most operating systems, even those which are aware of the Domain Name System (DNS), still offer backward compatibility with a locally administered list of foreign hosts. This configuration, for historical reasons, is stored in a flat text file that by default contains very few hostnames and their associated IP addresses. Editing this hosts file is simple and effective because most DNS clients will read the local hosts file before querying a remote DNS server. Storing black-hole entries in the hosts file prevents the browser from accessing an ad server by manipulating the name resolution of the ad server to a local or nonexistent IP address (127.0.0.1 or 0.0.0.0 are typically used for IPv4 addresses). While simple to implement, these methods can be circumvented by advertisers, either by hard-coding the IP address of the server that hosts the ads (this, in its turn, can be worked around by changing the local routing table by using for example iptables or other blocking firewalls), or by loading the advertisements from the same server that serves the main content; blocking name resolution of this server would also block the useful content of the site.

Using a DNS sinkhole by manipulating the hosts file exploits the fact that most operating systems store a file with IP address, domain name pairs which is consulted by most browsers before using a DNS server to look up a domain name. By assigning the loopback address to each known ad server, the user directs traffic intended to reach each ad server to the local machine or to a virtual black hole of /dev/null or bit bucket.

DNS cache

This method operates by filtering and changing records of a DNS cache. On most operating systems the domain name resolution always goes via DNS cache. By changing records within the cache or preventing records from entering the cache, programs are allowed or prevented from accessing domain names. The external programs monitor internal DNS cache and import DNS records from a file.[44] As a part of the domain name resolution process, a DNS cache lookup is performed before contacting a DNS server. Thus its records take precedence over DNS server queries. Unlike the method of modifying a Hosts file, this method is more flexible as it uses more comprehensive data available from DNS cache records.

DNS filtering

The filtering and selective blocking of DNS traffic can be performed by a DNS firewall which is configured to block DNS name resolution based on name patterns. A DNS firewall, such as Verigio DNS Firewall, can also block access to IP addresses for names not resolved via DNS. Thus prevent display of advertisements from servers accessed directly using their IP addresses.[45]

Advertising can be blocked by using a DNS server which is configured to block access to domains or hostnames which are known to serve ads by spoofing the address.[46] Users can choose to use an already modified DNS server or set up a dedicated device such as a Raspberry Pi themselves.[47] Manipulating DNS is a widely employed method to manipulate what the end user sees from the Internet but can also be deployed locally for personal purposes. China runs its own root DNS and the EU has considered the same. Google has required their Google Public DNS be used for some applications on its Android devices. Accordingly, DNS addresses / domains used for advertising may be extremely vulnerable to a broad form of ad substitution whereby a domain that serves ads is entirely swapped out with one serving more local ads to some subset of users. This is especially likely in countries, notably Russia, India and China, where advertisers often refuse to pay for clicks or page views. DNS-level blocking of domains for non-commercial reasons is already common in China.[48]

Hardware devices

Devices such as AdTrap use hardware to block Internet advertising.[49] Based on reviews of AdTrap, this device uses a Linux Kernel running a version of PrivProxy to block ads from video streaming, music streaming, and any Internet browser.[50] Another such solution is provided for network level ad blocking for telcos by Israeli startup Shine.[51]

By external parties and internet providers

Internet providers, especially mobile operators, frequently offer proxies designed to reduce network traffic. Even when not targeted specifically at ad filtering, these proxy-based arrangements will block many types of advertisements that are too large or bandwidth-consuming, or that are otherwise deemed unsuited for the specific internet connection or target device. Many internet operators block some form of advertisements while at the same time injecting their own ads promoting their services and specials.

Economic consequences for online business

Some content providers have argued that widespread ad blocking results in decreased revenue to a website sustained by advertisements[52][53] and e-commerce-based businesses, where this blocking can be detected. Some have argued that since advertisers are ultimately paying for ads to increase their own revenues, eliminating ad blocking would only dilute the value per impression and drive down the price of advertising, arguing that like click fraud, impressions served to users who use ad blockers are of little to no value to advertisers. Consequently, they argue, eliminating ad blocking would not increase overall ad revenue to content providers in the long run.[54][55]

Response from publishers

Countermeasures

Some websites have taken counter-measures against ad blocking software, such as attempting to detect the presence of ad blockers and informing users of their views, or outright preventing users from accessing the content unless they disable the ad blocking software, whitelist the website, or buy an "ad-removal pass". There have been several arguments supporting[56] and opposing[57] the assertion that blocking ads is wrong.[58]

Some publisher companies have taken steps to protect their rights to conduct their business according to prevailing law.[59] It has been suggested that in the European Union, the practice of websites scanning for ad blocking software may run afoul of the E-Privacy Directive.[60] This claim was further validated by IAB Europe's guidelines released in June 2016 stating that there indeed may be a legal issue in ad blocker detection.[61] While some anti-blocking stakeholders have tried to refute this[62][63] it seems safe to assume that Publishers should follow the guidelines provided by the main Publisher lobby IAB. The joint effort announced by IAB Sweden prior to IAB Europe's guideline on the matter never materialized, and would have most likely been found against European anti-competition laws if it did.

In August 2017, a vendor of such counter-measures issued a takedown notice under the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act, to demand the removal of a domain name associated with their service from an ad-blocking filter list. The vendor argued that the domain constituted a component of a technological protection measure, thus making it a violation of anti-circumvention law to frustrate access to it. [64][65]

Alternatives

As of 2015, advertisers and marketers look to involve their brands directly into the entertainment with native advertising and product placement (also known as brand integration or embedded marketing).[66] An example of product placement would be for a soft drink manufacturer to pay a reality TV show producer to have the show's cast and host appear onscreen holding cans of the soft drink. Another common product placement is for an automotive manufacturer to give free cars to the producers of a TV show, in return for the show's producer depicting characters using these vehicles during the show.

Some digital publications turned to their customers for help. For example, the Guardian is asking its readers for donations to help offset falling advertising revenue. According to the newspaper’s editor-in-chief, Katharine Viner, the newspaper gets about the same amount of money from membership and paying readers as it does from advertising.[67] The newspaper considered preventing readers from accessing its content if usage of ad-blocking software becomes widespread,[68] but so far it keeps the content accessible for readers who employ ad-blockers.

See also

References

- ↑ Elliott, Christopher (8 February 2017). "Yes, There Are Too Many Ads Online. Yes, You Can Stop Them. Here's How". Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- ↑ "IAB UK reveals latest ad blocking behaviour - IAB UK". iabuk.net. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- ↑ "Revenue Sources: A Heavy Dependence on Advertising". Pew Research Center's Journalism Project. 2014-03-26. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- ↑ Marshall, Jack (13 May 2016). "Forbes Tests New Tactics to Combat Ad Blocking". Archived from the original on 15 February 2017 – via www.wsj.com.

- ↑ Silverstein, Barry (2001). Internet Marketing for Information Technology Companies: Proven Online Techniques to Increase Sales and Profits for Hardware, Software and Networking Companies. Maximum Press. p. 130. ISBN 1885068670. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ↑ Simonite, Tom. "The New York Times, BBC, the NFL, and AOL recently served up malware inside their ads". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- ↑ "Internet Security". SecTheory. 24 October 2008. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ "Fine grained energy accounting on smartphones with Eprof" (PDF). Microsoft. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2012.

- 1 2 Della Costa, Chloe. Seven Tricks Advertisers Use To Manipulate You Into Spending More Money. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Becker, Sam. Do You Know Who Spends All Day Thinking About Your Kids? "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Templeman, Mike. 10 Marketing Tricks From the Pros "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Charski, Mindy. Programmatic Advertising: The Tools, Tips, and Tricks of the Trade. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Jantsch, John. Five Tips for Getting the Most Out of Online Advertising. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Becker, Joshua. Seven Reasons We Buy More Stuff Than We Need. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Eisenberg, Bryan. What Makes People Buy? 20 Reasons Why "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Five Fascinating Brain Tricks Publishers Use To Get You To See Their Ads "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ The Story of Stuff Project. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Marrs, Megan. 45 Fabulous Facebook Advertising Tips & Magic Marketing Tricks "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- 1 2 Pujol, Eric; Hohlfeld, Olive; Feldmann, Anja (17–21 August 2015). "Annoyed Users: Ads and Ad-Block Usage in the Wild" (PDF). London UK: ACM SigComm Conference. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2016.

- ↑ Chapin, Andrew. Stop Annoying People: How to Create Ads People Want to See. SemRush Blog, retrieved 1 June 2016. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Online Advertising More Likely to Spread Malware Than Porn". PCMAG. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017.

- ↑ "YouTube angeblich als Virenschleuder missbraucht". heise.de. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "The Wild Wild Web: YouTube ads serving malware". Bromium Labs. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014.

- ↑ "Firefox exploit found in the wild". Mozilla Security Blog. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "When you say advertising, I say block that malware". Engadget's Bad Password. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017.

- ↑ Australian Signals Directorate (February 2017). "Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents – Mitigation Details §User application hardening". asd.gov.au. Commonwealth of Australia. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

Block Internet advertisements using web browser software (and web content filtering in the gateway), due to the prevalent threat of adversaries using malicious advertising (malvertising) to compromise the integrity of legitimate websites to compromise visitors to such websites. Some organisations might choose to support selected websites that rely on advertising for revenue by enabling just their ads and potentially risking compromise.

- ↑ "A Guide to Avoid Being a Crypto-Ransomware Victim" (PDF). Webroot Inc. 2016. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

While many websites need advertisements to stay online, we have seen more and more popular websites (i.e. millions of visitors a year) infecting customers due to 3rd party hosted adverts on their websites – malvertising. [...] Ad blocker plugins can be installed and left without any user input and are very useful for stopping less technical users from being infected.

- ↑ Arana, Gabriel (19 October 2015). "Ad-Blocking Has Online Ad Industry On The Run". Archived from the original on 13 April 2016.

- ↑ "You say advertising, I say block that malware". Engadget. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017.

- ↑ Geigner, Timothy (11 January 2016). "After Begging You To Turn Off Adblocker, Serves Up A Steaming Pile Of Malware 'Ads". Forbes. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016.

- ↑ Kontaxis, Georgios; Chew, Monica (2015). "Tracking Protection in Firefox For Privacy and Performance" (PDF). IEEE Computer Society's Technical Committee on Security and Privacy.

- ↑ Aisch, Gregor; Andrews, Wilson; Keller, Josh (Oct 1, 2015). "The Cost of Mobile Ads on 50 News Websites". The New York Times. Retrieved Sep 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Upon startup multiple audio sources begin playing. I can't find the tab to kill them!". Support.mozilla.org. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- 1 2 "Look Who's Driving Adblock Growth". Fortune. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ Sweney, Mark (1 March 2016). "More than 9 million Britons now use adblockers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016.

- ↑ Sweney, Mark (20 April 2016). "Fears of adblocking 'epidemic' as report forecasts almost 15m UK users next year". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ "Konqueror browser features". Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ "Use Tracking Protection in Internet Explorer". Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ "Adblock Plus integrated into Maxthon browser". Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ "The browser for a web worth protecting". Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ "Under the hood: How Chrome's ad filtering works". Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ "Members - Coalition for Better Ads". Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ "Why Google's Ad-Blocking in Chrome Might Prove Awkward For the Company". Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ "Verigio Communications - Portable DNS Cache and Firewall for Windows". Verigio.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ "Verigio Communications - DNS Firewall for Windows". Verigio Communications Inc. 19 September 2016. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ "A Simple DNS-Based Approach for Blocking Web Advertising". Deer Run Associates. 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ↑ "Block Millions Of Ads Network-wide With A Raspberry Pi-hole 2.0". jacobsalmela.com. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ "The Extent of DNS Services Being Blocked in China". Circleid.com. 21 May 2010. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ "AdTrap - The Internet is yours again". BluePointSecurity.com. 18 August 2014. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ "AdTrap Product Review". Geek Inspector. Archived from the original on 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "This ad blocking company has the potential to tear a hole right through the mobile web — and it has the support of carriers". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ↑ Fisher, Ken (6 March 2010). "Why Ad Blocking is devastating to the sites you love". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ Jim Edwards (9 July 2015). "I used the software that people are worrying will destroy the web — and now I think they might be right". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016.

- ↑ Chappell, Richard (9 March 2010). "Does Ad Blocking Hurt Websites?". Philosophy, etc. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ Robles, Patricio (8 March 2010). "Is Ad Blocking Really Devastating to the Sites You Love?". Econsultancy. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ "Ad Blocking is Immoral | The Google Cache: Search Engine Marketing, SEO & PPC". The Google Cache. 2 August 2007. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ "Adblock: Adapt, or die. Service Assurance Daily: Anything and everything that affects IT performance, from the mundane to the bizarre - Network Performance Blog". Networkperformancedaily.com. 5 September 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ Kirk, Jeremy (23 August 2007). "Firefox ad-blocker extension causes angst | Applications". InfoWorld. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ "Confirmed: Even Adblock (without plus) will now display "Acceptable advertising" via Eyeo GmbH". Archived from the original on 3 October 2015.

- ↑ "Publishers snooping for ad blockers are breaking the law, claims privacy consultant". The Drum. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ "Ad Blocking Detection Guidance | IAB Europe". www.iabeurope.eu. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ↑ "About that claim that detecting Adblock may be illegal". Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ "Is blocking ad blockers really illegal in Europe?". Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ "How The DMCA's Digital Locks Provision Allowed A Company To Delete A URL From Adblock Lists". Techdirt. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ↑ Jones, Rhett (12 August 2017). "A Copyright Claim Was Reportedly Used to Stop Ad Blocking, But It's Complicated". Gizmodo. Gizmodo Media Group. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ "How Apple's embrace of ad blocking will change native advertising". Digiday. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ "Guardian relies on readers' support to stave off crisis". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ↑ "Guardian to consider preventing access to content if ad-blocking proliferates". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.