Ada Anderson

| Mme Ada Anderson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Ada Nymand 10th February 1843 London |

| Died | DOD unknown |

| Occupation | Pedestrianism and theatre |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | British |

Ada Anderson (née Nymand) was a British athlete famous for her feats of pedestrianism in the later half of the 19th century.

Early life

Her early life is not very well known. Her father Gustavas Nymand was reported to be a ‘Cockney Jew’, but the nationality of her mother was not known.[1] She left home at sixteen to join a theatre company and five years later married the man whose name she was most commonly known by. She claimed to have been a singer, clown, and theatre proprietress, with a childhood ambition to be famous by accomplishing something no one else could do.

Having struggled to make a name for herself as an actress Anderson and her husband became managers of a theatre in Cardiff.[2] But in 1877 her husband died, leaving Anderson on the brink of bankruptcy.

Career in pedestrianism

Anderson’s interest in pedestrianism started in 1877 when she met British champion racewalker William Gale at an event in Cardiff.[2] Unlike other working class pedestrians such as Emma Sharp who claimed to do no formal training, Anderson was trained by Gale who specialized both in pedestrianism and sleep deprivation. After training for six weeks with Gale, Anderson made her pedestrian debut in Newport, Wales in September 1877. She walked 1,000 half-miles (0.8 km, or 805 km total) in 1,000 half-hours and got no more than 20 minutes rest at one time during the entire three-week trek. There were several days of rain which required her to walk with an umbrella and a lamp but this did not prevent her from finishing.

Her second walk was planned to be 1,250 half-miles (2,012 km total) in 1,000 half-hours in Exeter, October 1877, which would break a record of 1,000 miles (1,609 km total) in 1,000 hours set by Captain Robert Barclay, but that had to be abandoned when a storm blew in. This did not deter Anderson and Gale, and they were able to accomplish that feat in Plymouth later that year. In addition to breaking the distance record by 250 miles (400 km), by starting each 1¼ mile (2.01 km) at the beginning of the hour (rather than completing two consecutive miles as Barclay did) Anderson completed the event with much shorter rest periods. After this event Anderson was referred to in the press as a ‘Champion Lady Walker of the World’.[3]

Anderson’s first indoor event was a 100-mile (80 km) 28-hour walk again in Plymouth. However the pollution from gas lamps and cigars gave Anderson problems breathing. After falling a number of times she collapsed unconscious after completing 96 miles (154 km). Following this failure Anderson went to the press and claimed she would ‘never take on another event she would not finish’. She completed 1,344 quarter-miles in the same number of quarter-hours in Plymouth and 1.5 miles (2.4 km) every hour for 28 days in Boston before attempting to equal Gale’s record of 1,500 miles (2,414 km) in 1,000 hours. Anderson started the event on 8 April 1878 and completed the event on 20 May 1878. Two days later, she got married for the second time to William Paley, a theatre man.[2]

After completing three more walks during the summer of 1878, Anderson established herself as the dominant pedestrian in the UK. Therefore, on 13 October 1878, with the aim of making a name for herself in the US, Anderson, Paley, her manager J. H. Webb and her assistant Elizabeth Sparrow sailed in the steamship Ethiopia across the Atlantic.

Mozart Garden – US debut

Anderson’s manager Webb wanted to launch her US debut (2,700 quarter-miles (1,086 km total) in 2,700 quarter-hours) in Glimore’s Garden (which later became Madison Square Garden). However, William Kissam Vanderbilt, the venue's owner rejected their request claiming ‘The woman will never accomplish the feat and nor can any woman’.[2] This led Webb to approach Mozart Garden, a smaller venue in Brooklyn which was refurbished for the event, reducing the seating from 2,000 to 800 to make way for a track which was surrounded by an 18-inch (460 mm) railing and measured by Brooklyn’s city surveyor to ensure accuracy. The venue was so small that the track was only 189 feet (58 m) in circumference, requiring Anderson to walk seven laps to complete each quarter of a mile (400 m). A ‘privacy tent’ was built for Anderson to use during her short rest periods containing a bed and a makeshift kitchen including a stove.[4] Walking 2,700 quarter-miles in so many quarter-hours was an accomplishment never attempted by any person before in the US, requiring an ability to endure severe sleep deprivation, leading the champion US pedestrian Daniel O'Leary to claim ‘he would not attempt it’.[5]

The event was so popular that the spectator fee was raised from 25 cents to 50 cents after 5/6 of the event had been completed. By the final day of the event ticket prices were $1 for standing and $2 for reserved seating. As many as 4,000 people a day came to see Anderson during the event which started on 16 December 1878. She completed the event on 13 January 1879 to a venue so packed that police had to prevent additional spectators. Many of the spectators were women whom it was reported regarded Anderson as 'the most wonderful of their sex'.[6]

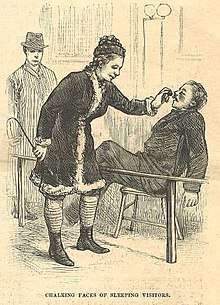

There were numerous checks and judges to ensure the integrity of the event and doctors who checked on Anderson concluded that she had trained herself to cope with sleep deprivation, since she had no more than nine minutes sleep at a time during the entire 28-day event. Fifty-five miles (88 km) into the event Anderson played the piano and sang Verdi’s “Back to Our Mountains” during her rest period and became known for such entertainment during the walk. Over the next few weeks she continued to entertain the crowds with impromptu singing and speeches. Anderson had a number of celebrities come and walk with her during the event including 75-year-old boxer Bill Tovec, General Tom Thumb and Texas Jack. She also entertained the crowd by marking the faces of sleeping spectators with coal. Because of the heavy wagers on the completion of the event, Anderson required protection in the final days of the walk. There were reports of attempted gassing with chloroform although Anderson denied this. With only half a mile to go Anderson sang ‘Nil Desperandum’ to the crowd before completing her penultimate lap. Her final quarter of a mile was then completed in 2 minutes 37 seconds the fastest of all 2,700. The total receipts of the event were reported to be $32,000 of which Anderson's personal share was reported to be $8,000.[2]

Health, sleep and nutrition

When asked by reporters about fatigue, Anderson claimed her biggest problem was often with blisters and the pain of them preventing her sleeping. However, the sleep deprivation became apparent even within the first two days where she had periods of stumbling through the walk in an almost semi-conscious state before appearing as lively as she was at the start a few hours later. In these sleepy periods her assistant Sparrow had to prepare her to walk at the three-minute warning bell and on occasion had to send her back to the track when she hadn’t completed the required seven laps. After 100 miles (160 km), the regular check by the a physician noted she had a temperature of 99 °F (37 °C), pulse 78-80 with her only complaints badly blistered feet and mental anxiety interfering with sleep.[7] Mike Henry, Anderson's coach, who walked with her for much of the event was not in such good health with blisters covering his feet and suffering from exhaustion and dizziness he had to retire, being replaced by one of the race judges Charles Hazelton. Anderson ate at almost every rest time unless she was sleeping and her diet included; beef, oysters, corned beef, potatoes, cakes and grapes, she drank beef tea, port wine and occasionally champagne.[2]

Critics of pedestrianism

Local magistrates in Boston, UK, objected to walking on Sundays believing that they corrupted morals. However Anderson found support in the local mayor who claimed that Boston was ‘more moral than Plymouth’ where Anderson had last walked on a Sunday.[2] The New York Times was also critical of Anderson’s journey stating it had no ‘”skill” attributes’ and the sport ‘leads people to bet on any absurd performance of uncertain issue’.[8] There were others who claimed that it was cruelty for a woman to be put through such suffering and claims during her walk in Chicago that her husband coerced her. To these criticisms Anderson responded ‘I am walking against my husband’s wishes’. Reverend W. C. Steele of the Third St. Methodist Church published sermons in a number of newspapers criticising pedestrianism for a number of reasons, including walking on a Sunday.[9][10]

Anderson's feats of pedestrianism

September 1877 – 1000 half miles in 1000 consecutive half hours (500 miles in 500 hours) Newport, Wales.

November 1877 – 1 ¼ miles every hour for 1000 hours. Plymouth, England.

December 1877 – 96 miles in 24 hours, Plymouth, England.

January 1878 -1,344 quarter-miles in as many quarter-hours, Plymouth, England.

February 1878 - 1,008 miles in 672 hours, Boston, England.

April 1878 – 1500 miles in 1000 hours, Leeds, England.

June 1878 - 1,008 miles in 672 hours, Skegness, England.

July 1878 - 864 quarter-miles in as many 5-minute periods, King's Lynn, England.

August 1878 - 1,344 quarter-miles in as many quarter-hours,Peterborough, England.

December 1878 - 2,700 quarter-miles in as many quarter-hours, Brooklyn, USA.

January 1879 - 1,350 quarter-miles in as many quarter-hours, Pittsburgh, USA.

May 1879 - 2,068 quarter-miles in as many quarter-hours, Chicago, USA.

April 1879 – 804 miles in 500 hours, Cincinnati, USA.

July 1879 - 2,028 quarter-miles in as many quarter-hours, Detroit, USA.

August 1879 - 2,052 quarter-miles in as many quarter-hours, Buffalo, USA.

December 1879 – 351 miles in 6 days, New York, USA.

May 1880 - 1,559 quarter-miles in as many 12-minute periods, Baltimore, USA.[11]

References

- ↑ Algeo, Matthew (2014). Pedestrianism. Independent Pub Group. ISBN 1613743971.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Harry., Hall, (2014). The pedestriennes : America's forgotten superstars. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Pub. ISBN 9781457534294. OCLC 898876817.

- ↑ "Champion Lady Walker of the World". Leeds Times. 4 May 1878.

- ↑ "A Long Walk". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 18 December 1878.

- ↑ "Madame Anderson: How Interest Grew". Brooklyn Eagle. 12 Jan 1879.

- ↑ "A Great Pedestrian Feat; Mme. Anderson Completes Her Task. the Plucky English Woman Before an Enthusiastic Brooklyn Audience Mozart Garden Crowded to Excess the Closing Scenes in the Hall". The New York Times. 13 January 1879.

- ↑ "Female Pedestrians". New York Times. 21 December 1878.

- ↑ "Tests of Endurance". The New York Times. 18 December 1878.

- ↑ "Municipal 'Is Sunday Pedestrianism Illegal?". Brooklyn Eagle. 17 March 1979.

- ↑ "Abuse of Pedestrianism". Brooklyn Eagle. 17 March 1879.

- ↑ "Ada Anderson acheivements". Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser,. May 16, 1880.

External links