Achim Müller

| Achim Müller | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

14 February 1938 Detmold, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Göttingen |

| Known for | Tailor-made porous nanoclusters and their use as versatile materials |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry, Nanoscience |

| Institutions | University of Bielefeld |

Achim Müller (born 14 February 1938 in Detmold, Germany) is a German scientist. He is Professor Emeritus at the Faculty of Chemistry, University of Bielefeld.

Academic career

Achim Müller studied chemistry and physics at the University of Göttingen and received there his PhD degree (1965) and the Habilitation (1967). In 1971, he became professor at the University of Dortmund and in 1977 professor of Inorganic Chemistry at the University of Bielefeld. In 2006 he got the Manchot-Forschungsprofessur of the Technische Universität München. He received but subsequently declined an invitation to succeed Professor F. Seel at Saarbrücken in 1982. His research involves mainly the chemistry of transition metals, especially with relation to nanochemistry,[1][2] but also to biochemistry (notably biological nitrogen fixation),[3] molecular magnetism [discovery of unique molecular magnets[4] of which one (V15) even allows the observation of quantum oscillations][5] and molecular physics (including theoretical studies of isotope-substitution changes on molecular constants and experimental investigations based on various sophisticated vibrational spectroscopic techniques, e.g. matrix isolation). He has also strong interest in history and philosophy of science.[6] He has published about 900 original papers in more than 100 different journals related to different fields, more than 40 reviews, presented ca. 130 plenary (30 opening) and invited lectures and is coeditor of 16 books (see External links below). Achim Müller is a member of the Leopoldina[7] and international academies, e.g. Polish Academy of Sciences, The Indian National Science Academy, National Academy of Exact Physical and Natural Sciences in Argentina, Academia Europaea. He has received many awards [honorary doctor degrees, e.g. of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) and the Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris as well as the “Profesor Honorario“ of the National University of La Plata] and prizes [ Alfred Stock Memorial Prize 2000, Prix Gay-Lussac/Humboldt 2001, Sir Geoffrey Wilkinson Prize 2001 (see Bibliography), Centenary Medal of the Royal Society of Chemistry 2008/9, London].[8] Furthermore, Achim Müller has presented several prominent/named lectures in different countries [England (Lord Jack Lewis in Cambridge), France (Perrin), Spain (Elhuyar-Goldschmidt), Sweden ("Berzelius Days")]. In 2012 he was awarded with the prestigious Advanced Grant by the European Research Council (ERC) (for more honors see External links). From Nature Chemistry he got an invitation to write an article about the future of Inorganic Chemistry for the first issue of the journal in 2009 (the Nobel prize winners R. Noyori and J. F. Stoddart reported about their topics). He is an Honorary Fellow of the Chemical Research Society of India.

Research

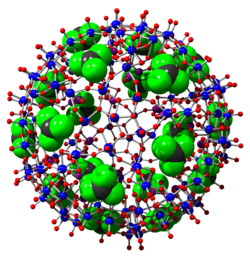

His current research relates mainly to bottom-up pathways towards tailor-made spherical porous metal oxide nanocapsules Mo132 Keplerates. These are soluble in water and are very probably one of the most versatile materials regarding applications in nanoscience.[1] It is evident that such applications are of interest not only for chemistry but also for biology, supramolecular chemistry and materials science as well as discrete mathematics.

The capsule has 20 well-defined pores with crown-ether functions which may be reversibly opened and closed. Substrates enter through these pores, and they can react to form a variety of species depending on the internal tapestry of the nanocontainer. This inorganic nanocell also allows ion transport through the cavity. Several new phenomena under confined conditions can be studied by variation of the internal ligands with hydrophilic and/or hydrophobic character, based on a variety of reactive substrates inside (for the interdisciplinary character of the whole compound class see Ref.[9]). The applications include the following topics:

- Investigating processes, including catalytic ones, under confined conditions, especially in capsules with stepwise tunable pores and tunable internal functions

- Coordination chemistry at surfaces, in pores and in cavities of nanocapsules: sphere-surface supramolecular chemistry, controlled exchange of guests at different internal sites with each other and with the outside, nano ion-chromatography, nucleation processes under confined conditions

- Modelling ion transport across transmembrane channels

- New insights into hydrophobic interactions, e.g. thermodynamics of hydrophobic clustering, sequestration of hydrophobic organic pollutants, and nano-dewetting

- Structure and dynamics of encapsulated high and low density water

- Towards multifunctionality and hierarchical complexity: examples for chemical adaptability and for a supramolecular chemical Darwinism, self-assembly of capsules into various patterns in different phases (e.g. blackberry-like hollow spherical assemblies as well as two- and three-dimensional structures)

Müller's discovery of the molecular giant spheres (Keplerates) of the type Mo132 (diameter ca. 3 nm) and their derivatives,[1][10] of the wheel shaped cluster Mo154 (Refs.[1] and [11]) and hedgehog shaped cluster Mo368[1] (as large as 6 nm) has caused a paradigm shift due to the unique structural features and huge application range of these molecular nanoclusters. These single molecules are quite large; this can be shown by taking the length of an oxygen molecule with two atoms (length 0.12 nm) as a unit, then considering Mo368 which is 50 times larger. Müller's related work shows many applications (see above), for example, how cellular processes like ion-transport can be modelled based on the spherical porous capsules[12][13] and how the latter can be used to remove toxic compounds from water.[14] All the mentioned nanomaterials belong to a class commonly termed polyoxometalates and some special ones to the molybdenum blue family; the elucidation by Müller of the chemical nature of molybdenum blue was a real tour de force.[15][16] The compounds are studied worldwide by many groups especially in relation to potential applications in Materials Science (see Ref.[1] and below). One aspect is modelling of the Lotus effect,[17] another one is chemical adaptability as a new phenomenon.[18] An interesting mathematical treatment of the Keplerates could be developed in relation to spherical viruses and Buckminster Fuller Domes based on Archimedean and Platonic solids.[19] The unique range of potential applications of the Mo132 Keplerates has also been highlighted by several other authors, e.g.:[20] "Thus, Keplerate-type capsules represent unique supramolecular objects offering a tunable spatially-restricted environment and promising in many domains such as catalysis, electric conductivity, non-linear optics, liquid crystals, vesicles and "blackberry" aggregates. ...a key point to promote confined space engineering." In another publication [21] it is written: "Initiated and led by Müller and co-workers, the synthesis and structural characterization of protein-sized metal oxide clusters (2-6 nm) have generated great interest in the areas of physics, biology, chemistry, and materials science"; see also regarding a similar comment Ref.[22] Some of the clusters can be obtained by planned synthesis,[23] while the related derivative (also because of the structure of a Keplerate[4][19]) Mo72Fe30 has unique magnetic properties.[1][4] There are two older synthetic topics where Achim Müller did pioneering work. This refers to basic simple transition metal sulphur compounds, including related hydrodesulfurization catalysis and a new type of host guest chemistry based on polyoxovanadates[2] (for both topics see especially the three Honorary Issues under Bibliography). One paper about polyoxometalates was cited ca. 2000 times.[24] The publications of Achim Müller were highlighted many times in the media and related magazines.[25] Important last sentences: “Giant polyoxometalates (POMs) are of particular interest, as they are the largest inorganic molecules ever made, combined with fascinating structures and manifold applications in catalysis, medicine and material sciences. Typically, Müller‘s group has achieved great success in creating giant polyoxomolybdates (POMos) during the past two decades, establishing a series of incredibly large POMos with hundreds of Mo centers, such as {Mo132}, {Mo154}, {Mo176}, {Mo248} and {Mo368}. Especially {Mo368}, with more than 360 Mo atoms, still is the largest POM to date...“[26]

Personal

Müller likes ancient Greek philosophy, classical music, and mountain hiking. He has a love for woodland birds since his early childhood, a pastime which his father cherished also.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 a) From linking of metal-oxide building blocks in a dynamic library to giant clusters with unique properties and towards adaptive chemistry, A. Müller, P. Gouzerh, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2012, 41, 7431; b) Capsules with Highly Active Pores and Interiors: Versatile Platforms at the Nanoscale, A. Müller, P. Gouzerh, Chem. Eur. J. (Concept), 2014, 20, 4862.

- 1 2 a) Supramolecular Inorganic Chemistry: Small Guests in Small and Large Hosts, A. Müller, H. Reuter, S. Dillinger, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1995, 34, 2328; b) Induced molecule self-organization, A. Müller, Nature, 1991, 352, 115.

- ↑ a) Iron-Only Nitrogenase: Exceptional Catalytic, Structural and Spectroscopic Features, in: Catalysts for Nitrogen Fixation: Nitrogenases, Relevant Chemical Models, and Commercial Processes, K. Schneider, A. Müller (Eds.: B. E. Smith, R. L. Richards, W. E. Newton), Kluwer, Dordrecht, 2004, p. 281; b) Towards Biological Supramolecular Chemistry: A Variety of Pocket-Templated, Individual Metal Oxide Cluster Nucleations in the Cavity of a Mo/W-Storage Protein, J. Schemberg, K. Schneider, U. Demmer, E. Warkentin, A. Müller, U. Ermler, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2007, 46, 2408; corrigendum: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2007, 46, 2970.

- 1 2 3 a) Structure-related frustrated magnetism of nanosized polyoxometalates: aesthetics and properties in harmony, P. Kögerler, B. Tsukerblat, A. Müller, Dalton Trans. (Perspective), 2010, 39, 21; b) Molecular Nanomagnets, D. Gatteschi, R. Sessoli, J. Villain, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006 (chapters 4.4 and 14.3).

- ↑ Quantum oscillations in a molecular magnet, S. Bertaina, S. Gambarelli, T. Mitra, B. Tsukerblat, A. Müller, B. Barbara, Nature, 2008, 453, 203; corrigendum: Nature, 2010, 466, 1006 (V15).

- ↑ For example: a) Die inhärente Potentialität materieller (chemischer) Systeme, A. Müller, Philosophia naturalis, 1998, Bd. 35, Heft 2, 333; b) Naturgesetzlichkeiten – Chemie lediglich ein Bereich zwischen Physik und biologischem Geschehen? A. Müller, Philosophia naturalis, 2000, Bd. 37, Heft 2, 351; c) Chemie und Ästhetik - die Formenvielfalt der Natur als Ausdruck ihrer Kreativität, A. Müller, ZiF (Center for Interdisciplinary Research), Mitteilungen, 1999, 4, 7; d) Science, Society, and Hopes of a Renaissance Utopist, A. Müller, Science & Society, 2000, 1, 23.

- ↑ http://www.leopoldina.org/en/members/list-of-members/member/548/ Nationale Akademie der Wissenschaften Leopoldina.

- ↑ http://www.rsc.org/ScienceAndTechnology/Awards/CentenaryPrizes/Prevwinner1.asp

- ↑ Molecular growth from a Mo176 to a Mo248 cluster, A. Müller, S. Q. N. Shah, H. Bögge, M. Schmidtmann, Nature, 1999, 397, 48.

- ↑ Picking up 30 CO2 Molecules by a Porous Metal Oxide Capsule Based on the Same Number of Receptors, S. Garai, E. T. K. Haupt, H. Bögge, A. Merca, A. Müller, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2012, 51, 10528.

- ↑ a) Self-assembly in aqueous solution of wheel-shaped Mo154 oxide clusters into vesicles, T. Liu, E. Diemann, H. Li, A. W. M. Dress, A. Müller, Nature, 2003, 426, 59; b) Hierarchic patterning: architectures beyond 'giant molecular wheels', A. Müller, E. Diemann, C. Kuhlmann, W. Eimer, C. Serain, T. Tak, A. Knöchel, P. K. Pranzas, Chem. Commun., 2001, 1928; c) Polyoxomolybdate Clusters: Giant Wheels and Balls, A. Müller, S. K. Das, E. Krickemeyer, C. Kuhlmann (checked by: M. Sadakane, M. H. Dickman, M. T. Pope), Inorganic Syntheses, Editor J. R. Shapley, 2004, 34, 191.

- ↑ Guests on Different Internal Capsule Sites Exchange with Each Other and with the Outside, O. Petina, D. Rehder, E. T. K. Haupt, A. Grego, I. A. Weinstock, A. Merca, H. Bögge, J. Szakacs, A. Müller, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 410.

- ↑ Mimicking Biological Cation-Transport Based on Sphere-Surface Supramolecular Chemistry: Simultaneous Interaction of Porous Capsules with Molecular Plugs and Passing Cations, A. Merca, E. T. K. Haupt, T. Mitra, H. Bögge, D. Rehder, A. Müller, Chem. Eur. J., 2007, 13, 7650.

- ↑ a) Hydrophobic Interactions and Clustering in a Porous Capsule: Option to Remove Hydrophobic Materials from Water, C. Schäffer, A. M. Todea, H. Bögge, O. A. Petina, D. Rehder, E. T. K. Haupt, A. Müller, Chem. Eur. J., 2011, 17, 9634; b) Densely Packed Hydrophobic Clustering: Encapsulated Valerates Form a High-Temperature-Stable {Mo132} Capsule System, S. Garai, H. Bögge, A. Merca, O. A. Petina, A. Grego, P. Gouzerh, E. T. K. Haupt, I. A. Weinstock, A. Müller, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2016, 55, 6634 (front cover picture).

- ↑ Soluble Molybdenum blues - "des Pudels Kern", A. Müller, C. Serain, Acc. Chem. Res., 2000, 33, 2.

- ↑ a) A Nanosized Molybdenum Oxide Wheel with a Unique Electronic-Necklace Structure: STM Study with Submolecular Resolution, D. Zhong, F. L. Sousa, A. Müller, L. Chi, H. Fuchs, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2011, 50, 7018; b) From Scheele and Berzelius to Müller: Polyoxometalates (POMs) revisited and the "missing link" between the bottom up and top down approaches, P. Gouzerh, M. Che, l’actualité chimique, 2006, June Issue, No. 298, 9.

- ↑ Water Repellency in Hydrophobic Nanocapsules - Molecular View on Dewetting, A. Müller, S. Garai, C. Schäffer, A. Merca, H. Bögge, A. J. M. Al-Karawi, T. K. Prasad, Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 6659 (front cover picture).

- ↑ Chemical Adaptability: The Integration of Different Kinds of Matter into Giant Molecular Metal Oxides, A. Müller, A. Merca, A. J. M. Al-Karawi, S. Garai, H. Bögge, G. Hou, L. Wu, E. T. K. Haupt, D. Rehder, F. Haso, T. Liu, Chem. Eur. J., 2012, 18, 16310 (front cover picture).

- 1 2 a) Spherical (Icosahedral) Objects in Nature and Deliberately Constructable Molecular Keplerates: Structural and Topological Aspects, O. Delgado, A. Dress, A. Müller, in: Polyoxometalate Chemistry: From Topology via Self-Assembly to Applications (Eds.: M. T. Pope, A. Müller), Kluwer, Dordrecht, 2001, 69; b) A chemist finds beauty in molecules that resemble an early model of the Solar System, A. Müller, Nature, 2007, 447, 1035; c) The Beauty of Symmetry, A. Müller, Science, 2003, 300, 749.

- ↑ Tunable Keplerate Type-Cluster "Mo132" Cavity with Dicarboxylate Anions, T.-L. Lai, M. Awada, S. Floquet, C. Roch-Marchal, N. Watfa, J. Marrot, M. Haouas, F. Taulelle, E. Cadot, Chem. Eur. J., 2015, 21, 13311.

- ↑ Reduction-Triggered Self-Assembly of Nanoscale Molybdenum Oxide Molecular Clusters, P. Yin, B. Wu, T. Li, P. V. Bonnesen, K. Hong, S. Seifert, L. Porcar, C. Do, J. K. Keum, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2016, 138, 10623.

- ↑ X-ray and Neutron Scattering Study of the Formation of Core-Shell-Type Polyoxometalates, P. Yin, B. Wu, E. Mamontov, L. L. Daemen, Y. Cheng, T. Li, S. Seifert, K. Hong, P. V. Bonnesen, J. K. Keum, A. J. Ramirez-Cuesta, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2016, 138, 2638.

- ↑ Spontaneous self-assembly of a giant spherical metal-oxide Keplerate: addition of one building block induces "immediate" formation of the complementary one from a constitutional dynamic library, C. Schäffer, A. M. Todea, P. Gouzerh, A. Müller, Chem. Commun., 2012, 48, 350.

- ↑ Polyoxometalate Chemistry: An Old Field with New Dimensions in Several Disciplines, M. T. Pope, A. Müller, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1991, 30, 34.

- ↑ Like Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Die Welt, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Handelsblatt, Göttinger Tagesblatt, The Hindu, El Pais, Gazeta Wyborcza, Situs Kimia Indonesia, Times of India, Science in Siberia, Scientific American, American Mathematical Society, New Scientist, Chemistry World, Chemistry in Britain, Materials Today, Spektrum der Wissenschaft, Bild der Wissenschaft, Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau, Chem. i. u. Zeit, La Recherche, Der Spiegel. For details see and Reference 6 c) Mitteilungen.

- ↑ {Nb288O768(OH)48(CO3)12}: A Macromolecular Polyoxometalate with Close to 300 Niobium Atoms, Y.-L. Wu, X.-X. Li, Y.-J. Qi, H. Yu, L. Jin, S.-T. Zheng, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2018, 57, 8572.

Bibliography

- Honorary Issue of Inorganica Chimica Acta (Biography) with a dedication by E. Diemann and B. Krebs, 2010, 363, 4145.

- Honorary Issue of Journal Cluster Science with Foreword by M. T. Pope, 2003, 14, 189.

- Honorary Issue of Journal of Molecular Structure with a Dedication by A. J. Barnes, E. Diemann, and H. Ratajczak, 2003, 656, 1.

- Prof. Achim Müller awarded 2001 Sir Geoffrey Wilkinson Prize, S. Migchielsen, G. Férey, Solid State Sciences, 2002, 4, 753 ; past winners include: M. F. Hawthorne (1993), F. A. Cotton (1995), Lord Jack Lewis (1997).

- In a section about Achim Müller of F. A Cotton’s book (pp 310/11): My Life in the Golden Age of Chemistry: More Fun Than Fun, the author writes: “'The Most Unforgetable Character I Have Met.' For me Achim Müller could be that man."

See also the following titles:

- Inorganic Molecular Capsules: From Structure to Function, L. Cronin, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2006, 45, 3576.

- Bringing inorganic chemistry to life, N. Hall, Chem. Commun., 2003, 803 (focus article).

- Author Profile, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2013, 52, 800.

- See additionally Reference 16 b) l’actualité chimique.