2013 Berlin helicopter crash

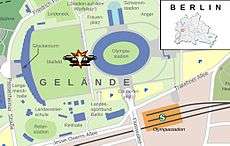

Map of the crash site | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 21 March 2013 |

| Summary | Two German Federal Police helicopters collided during training exercise |

| Site |

Olympic Stadium, Berlin, Germany 52°30′49″N 13°14′10″E / 52.513492°N 13.23614°ECoordinates: 52°30′49″N 13°14′10″E / 52.513492°N 13.23614°E |

| Total fatalities | 1 |

| Total injuries | 8 |

| First aircraft | |

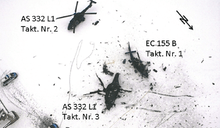

The wreck of aircraft D-HLTM after the crash | |

| Type | Eurocopter EC 155 |

| Operator | Federal Police |

| Registration | D-HLTM[1] |

| Passengers | 8 |

| Crew | 2 |

| Fatalities | 1 |

| Survivors | 9 |

| Second aircraft | |

The wreck of aircraft D-HEGB after the crash | |

| Type | Eurocopter AS332 Super Puma |

| Operator | Federal Police |

| Registration | D-HEGB[2] |

| Passengers | 13 |

| Crew | 2 |

| Survivors | 15 |

On 21 March 2013 around 10:30 CET, two helicopters of the German Federal Police collided in front of the Olympic Stadium in Berlin. Amid a large-scale training exercise, one helicopter apparently touched the other while landing in snowy weather. The accident left one pilot dead and injured several other persons.

Event

During a large police exercise against football hooliganism on 21 March 2013 at the Olympic Stadium of Berlin, three helicopters of the federal German police force were scheduled to land on the Maifeld sports field in front of the stadium. Their task was the delivery of reinforcements for police at the nearby railway station. The flight comprised two Eurocopter AS332 Super Pumas and one Eurocopter EC 155.[3]

Landing zone crash

The final investigation report describes the event as follows: The first aircraft, an EC 155, landed successfully around 10:28 but raised large amounts of snow from the ground. This helicopter carried the pilot, an engineer, seven police officers, and one journalist. It was followed by the Super Puma, which approached the landing zone at a steep angle and hovered back and forth above the ground for about 30 seconds, raising ever more snow that fully engulfed the first helicopter. During this manoeuvre, the third helicopter, also a Super Puma, approached the landing zone, carrying the pilot, an engineer, and 13 officers. This third aircraft also raised a large cloud of snow from the ground while landing, causing the pilot to lose sight of the marshalling officer on the ground. The third helicopter then touched the ground which caused the aircraft to roll over. Thereby its main rotor and tail section collided with the EC155's main rotor. The pilot of the EC155 was killed by a piece of rotor blade. Apart from a landing report made by helicopter number one and a brief report on changing positions during the landing approach of aircraft number two and three, no radio communication took place between the three aircraft during the entire landing phase.[4][5]

Apart from a report about the successful landing of aircraft No. 1 and brief announcements of shifting positions during their approach, no radio messages had been exchanged between the three helicopters. Helicopter No. 1 (EC 155) was equipped with a cockpit voice recorder and a flight data recorder. The crashed Super Puma was equipped with a cockpit voice recorder but did not carry a flight data recorder since that was not a legal requirement when the type was first certified in 1989. Voice recorder data did not indicate any warnings about potential technical problems during the landing approach.[3]

Meteorological conditions

Visibility of 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) had been reported at 10:20 a.m. from Tegel Airport, three nautical miles from the stadium. Cloud coverage was broken with winds of 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph) from 310 degrees. Air temperature was −1 °C (30 °F), air pressure was 1015 hPa. Investigators measured a layer of snow of 17 centimetres (6.7 in) outside the crash site. During the morning, the air temperature had further decreased, so that the old snow cover was frozen with fresh snow lying on top. The total snow thickness at the crash site was recorded as 15 centimetres (5.9 in).[3]

The interim investigation report and the final assessment noted that helicopter landings on snow-covered terrain are not something unusual and that there are standard procedures for preventing a so-called whiteout. The final report, however, marked that the federal police did not have any such standards in their flying instructions.[3][4]

Immediate reactions

After the disaster, the police exercise was criticised by members of the state parliament of Berlin. Delegates of Alliance '90/The Greens and The Left questioned the use of helicopters during the bad weather conditions on the day of the exercise, and called the training scenario "unrealistic" and "disproportionate".[6] Members of the Federal Police and politicians of the SPD and CDU stated, however, that such exercises were especially useful even in bad weather conditions, since real missions still have to be carried out in bad weather. The Greens and The Left also announced that they would debate the topic in the interior committee of the state parliament.[6][7]

Hans-Peter Friedrich, Federal Minister of the Interior, and Berlin senator of the interior Frank Henkel visited the site of the crash on 21 March and offered their condolences to the victims and their families.[8] Chancellor Angela Merkel announced her commiserations via her press officer Steffen Seibert.[9]

Wolfgang Bosbach, head of the interior commission of the parliament of Germany, announced that the helicopter crash would be added to the list of subjects in a planned debate about the future structure of the federal police forces.[6][10]

Investigation

The German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Investigation and federal attorneys investigated the accident, and a special homicide commission was routinely established at the Berlin State Office of Criminal Investigation.[11][12][13] In the night of 22 March, the wrecked aircraft were hauled to a police facility in Ruhleben. A post-mortem examination of the dead pilot concluded that he had obviously been killed by extraneous causes resulting from the crash.[11] Following these findings, the special homicide commission was dissolved.[6]

A first report by the Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Investigation was published in May 2013. It listed the known facts of the accident without identifying a cause.[14] The cause of the accident was still unclear as of September 2013.[15]

Final report and criticism

The final investigation report was published in September 2014. The investigators stated that all pilots had ample flying experience including landings in snow, dust and sand. The pilot of helicopter No. 2 had also been flying search-and-rescue missions in mountainous areas so he was familiar with landing on unprepared snowy ground.[4]

According to the investigation, a number of circumstances led to the fatal crash: the federal police aviation did not have any distinctive procedure for landings on snowy ground, the distances between the three individual aircraft during the landing phase had been too small, and communication between the personnel involved in the landing operation had been too scarce. The final investigation report also criticised that while the German federal police helicopter squadron was the nation's biggest non-military helicopter operator, it was not bound to the legal framework of similar civilian aviation companies. Notably European Union directive No. 216/2008 was criticised for exempting police aviation from such legal control. Also safety recommendations for police helicopter aviation issued by the Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Investigation to the federal ministry of transport in 2006 had not been legally implemented.[4][6]

The president of the German federal police rejected the report and claimed that own investigations had shown different results. The distance between the aircraft had been sufficient, and the communication had been reduced to a minimum according to the planned mission. Police pilots unofficially criticised the chief investigator who is a military pilot and had allegedly used inapplicable standards for the investigation. A motion to disqualify the investigator was however rejected.[16]

Aftermath

Following the crash, the federal police introduced special training units and new rules for helicopter landings in snow.[17] In February 2017, it was reported that NATO was prompted by the 2013 Olympiastadion crash to initiate a multinational trials campaign for new technologies in low-visibility helicopter flights.[18]

References

- ↑ "Hubschrauber-Absturz auf dem Berliner Maifeld" [Helicopter Crash at the Berlin Maifeld]. Berliner Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Helikopter-Wracks abtransportiert" [Helicopter Wrecks hauled off]. Berliner Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 2013-03-31. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Zwischenbericht" [Interim Report]. Bulletin: Unfälle und Störungen beim Betrieb ziviler Luftfahrzeuge. März 2013 (in German). German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Investigation (1303): 43–59. May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Untersuchungsbericht BFU 3X010-13" (PDF) (in German). Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Investigation. 23 September 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ↑ During, Rainer W. (9 October 2014). "Bundespolizeipräsident distanziert sich von kritischem Absturzbericht". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hasselmann, Jörn; Hense, Kerstin; During, Rainer (22 March 2013). "Hubschrauber-Unglück am Olympiastadion. Berlin Grüne und Linke: Übung hätte abgebrochen werden müssen" [Helicopter Accident at Olympic Stadium. Greens and Left: Exercise should have been called off]. Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ Nibbrig, Hans H. (24 March 2013). "Helikopterabsturz wird Thema im Berliner Parlament" [Helicopter crash will become an issue in the Berlin parliament]. Berliner Morgenpost (in German). Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ Witte, Jens (21 March 2013). "Hubschrauber-Unglück in Berlin: Tod im Schneetreiben" [Helicopter Disaster in Berlin: Death in a Snow Flurry]. Der Spiegel (in German). Deutsche Presse-Agentur, Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Merkel bestürzt über Hubschrauberunglück in Berlin" [Merkel dismayed over Helicopter Crash]. Die Welt (in German). Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 22 March 2013. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Die letzten Momente im Heli-Cockpit" [Last Moments in the Helo Cockpit]. B.Z. (in German). 22 March 2013. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- 1 2 Schnedelbach, Lutz (22 March 2013). "Hubschrauber-Absturz am Olympiastadion. Monatelange Suche nach Ursache beginnt" [Helicopter Crash at Olympic Stadium. Months-long Search for Cause has started]. Berliner Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ Greenwood, Faine; Phelan, Jessica (21 March 2013). "Two Helicopters Crashed In Mid-Air In Berlin". Business Insider. GlobalPost. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Pilot stirbt bei Hubschrauber-Crash" [Pilot dies in Helicopter Crash]. Mittelbayerische Zeitung (in German). 21 March 2013. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Zwischenbericht schildert Hubschrauber-Absturz in Berlin" [Interim report describes Helicopter Crash in Berlin]. Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (in German). 29 May 2013. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ "Ursache für tödlichen Hubschrauber-Absturz noch nicht bekannt". Berlin Aktuell (in German). City of Berlin. Deutsche Presseagentur. 20 September 2013. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013.

- ↑ Behrendt, Michael; Gandzior, Andreas (9 October 2014). "Gutachterstreit um tödlichen Hubschrauberabsturz". Berliner Morgenpost (in German). Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ↑ Schöbel, Sebastian (9 October 2014). "Hubschrauberabsturz hätte verhindert werden können". Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (in German). Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ↑ Pehl, Bernhard (9 February 2017). "Blindflug durch Blau und Orange". Donaukurier (in German). Retrieved 3 March 2017.

Auch Unfälle kommen immer wieder vor, wie etwa im März 2013 bei einer Großübung im Berliner Olympiastadion, was die eigentliche Initialzündung für die Kampagne war. [Also accidents tend to happen, e. g. in March 2013 during a large-scale exercise at the Berlin Olympiastadion, which actually sparked the trials campaign.]

External links

![]()