1872 Cavite mutiny

| Cavite mutiny | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Philippine revolts against Spain | |||||||

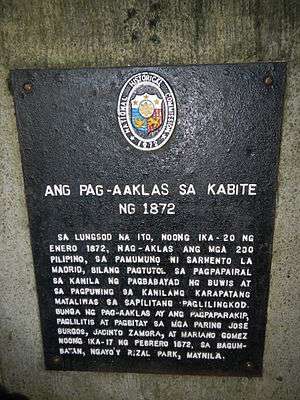

"Ang Pag-aaklas sa Kabite ng 1872" historical marker for the Cavite mutiny at Fort San Felipe in Cavite City, 1872 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Spanish Empire |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| One regiment, four cannons | Around 200 soldiers and laborers | ||||||

The Cavite mutiny of 1872 was an uprising of Filipino military personnel of Fort San Felipe, the Spanish arsenal in Cavite,[1]:107 Philippine Islands (then also known as part of the Spanish East Indies) on January 20, 1872. Around 200 locally recruited colonial troops and laborers rose up in the belief that it would elevate to a national uprising. The mutiny was unsuccessful, and government soldiers executed many of the participants and began to crack down on a burgeoning Philippines nationalist movement. Many scholars believe that the Cavite Mutiny of 1872 was the beginning of Filipino nationalism that would eventually lead to the Philippine Revolution of 1896.[2]

Causes

The primary cause of the mutiny is believed to be an order from Governor-General Rafael de Izquierdo to subject the soldiers of the Engineering and Artillery Corps to personal taxes, from which they were previously exempt. The taxes required them to pay a monetary sum as well as to perform forced labor called, polo y servicio. The mutiny was sparked on January 20, when the laborers received their pay and realized the taxes as well as the falla, the fine one paid to be exempt from forced labor, had been deducted from their salaries.

Battle

Their leader was Fernando La Madrid, a mestizo sergeant with his second in command Jaerel Brent Pedro, a moreno. They seized Fort San Felipe and killed eleven Spanish officers. The mutineers thought that fellow Filipino indigenous soldiers in Manila would join them in a concerted uprising, the signal being the firing of rockets from the city walls on that night.[1]:107 Unfortunately, what they thought to be the signal was actually a burst of fireworks in celebration of the feast of Our Lady of Loreto, the patron of Sampaloc. News of the mutiny reached Manila, the Spanish authorities feared for a massive Filipino uprising. The next day, a regiment led by General Felipe Ginovés besieged the fort until the mutineers surrendered. Ginovés then ordered his troops to fire at those who surrendered, including La Madrid. The rebels were formed in a line, when Colonel Sabas asked who would not cry out, "Viva España", and shot the one man who stepped forward.[1]:107 The remainder were sent to prison.[1]:107

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath of the mutiny, some Filipino soldiers were disarmed and later sent into exile on the southern island of Mindanao. Those suspected of directly supporting the mutineers were arrested and executed. The mutiny was used by the colonial government and Spanish friars to implicate three secular priests, Mariano Gómez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, collectively known as Gomburza. They were executed by garrote on the Luneta field, also known in the Tagalog language as Bagumbayan, on 17th February 1872.[1]:107 These executions, particularly those of the Gomburza, were to have a significant effect on people because of the shadowy nature of the trials. José Rizal, whose brother Paciano was a close friend of Burgos, dedicated his work, El filibusterismo, to these three priests.

On January 27, 1872, Governor-General Rafael Izquierdo approved the death sentences on forty-one of the mutineers. On February 6, eleven more were sentenced to death, but these were later commuted to life imprisonment. Others were exiled to other islands of the colonial Spanish East Indies such as Guam, Mariana Islands, including the father of Pedro Paterno, Maximo Paterno, Antonio M. Regidor y Jurado, and José María Basa.[1]:107–108 The most important group created a colony of Filipino expatriates in Europe, particularly in the Spanish capital of Madrid and Barcelona, where they were able to create small insurgent associations and print publications that were to advance the claims of the seeding Philippine Revolution.

Finally, a decree was made, stating there were to be no further ordinations /appointments of Filipinos as Roman Catholic parish priests.[1]:107 In spite of the mutiny, the Spanish authorities continued to employ large numbers of native Filipino troops, carabineros and civil guards in their colonial forces through the 1870s–1890s until the Spanish–American War of 1898.[3]

Back story

During the short trial, the captured mutineers testified against José Burgos. The state witness, Francisco Saldua, declared that he had been told by one of the Basa brothers that the government of Father Burgos would bring a navy fleet of the United States to assist a revolution with which Ramón Maurente, the supposed field marshal, was financing with 50,000 pesos. The heads of the friar orders held a conference and decided to dispose Burgos by implicating him to a plot. One Franciscan friar disguised as Burgos and suggested a mutiny to the mutineers. The senior friars used an una fuerte suma de dinero or a banquet to convince Governor-General Rafael de Izquierdo that Burgos was the mastermind of the coup. Gómez and Zamora were close associates of Burgos, so they too were included in the allegations.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Foreman, J., 1906, The set course for her patrol area off the northeastern coast of the main Japanese island Honshū. She arrived, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

- ↑ Chandler, David P. In search of Southeast Asia: a modern history. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1110-0.

- ↑ Field, Ron. Spanish–American War 1898. pp. 98–99. ISBN 1-85753-272-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1872 Cavite mutiny. |