A Brief History of Europe is a free content online book published on English Wikibooks.

Preface

A Brief History of Europe covers European history from the fall of Rome to the present day.

This period can roughly be divided into the Middle Ages, and the modern period. The modern period includes the contemporary period.

Author(s)

Jules (Mrjulesd)

Sources

Primarily articles on the English Wikipedia.

For this reason it should not be directly cited. It is recommended instead to search for the italicized term on Wikipedia, and refer to the citations on the relevant article.

Notes

c. = circa or century.

Comments

Any comments? Please comment here.

See also

Part 1 Middle Ages

The Middle Ages (or medieval period) lasted roughly from the 5th to the 15th century. It can be considered as from the period from the end of classical antiquity with the fall of Rome in 476, to the fall of Constantinople in 1453. It followed Classical antiquity, which was circa 8th –7th century BC to the fall of Rome. Medium aevum (Latin for middle age) gave rise to the term “medieval”.

It can be divided into:

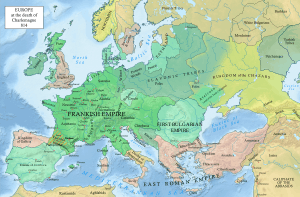

- Early Middle Ages, which was circa AD 500–1000, and sometimes referred to as the Dark Ages, although this is controversial. It was a time of new empire building, most importantly Francia (the Frankish empire). The rise of Islam created a rivalry with the Byzantine Empire, and Iberia would soon be conquered by them.

- High Middle Ages, which was circa AD 1000–1300, or 1000–1250. After the Norman conquest of England, the English Plantagenet dynasty would rival the French kings for France. The Holy Roman Empire would get established as a powerful Germanic empire. There was religious turmoil with the crusades, and with the Great Schism the Catholic and Orthodox churches would separate.

- Late Middle Ages was circa AD 1300–1500 or 1250–1500. The Crisis of the Late Middle Ages was a series of famines, plagues, peasant revolts, and wars, that devastated European populations. It was also the period of the rise of the Ottoman Empire, who would overthrow the Byzantine Empire and come to dominate the Balkans.

See also Wikipedia:Middle Ages.

Chapter 1 Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages was Circa AD 500–1000; it is sometimes referred to as the Dark Ages, as there was a relative scarcity of literary and cultural output in Western Europe.

See also Wikipedia:Early Middle Ages

Peoples of the Early Middle Ages

Germanic peoples

Germanic peoples can be divided into West, East and North:

West Germanic peoples included:

- Anglo-Saxons, the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes; they inhabited Jutland and northern Europe, and founded Anglo-Saxon England (c. 500–1066).

- Franks, that spread across Europe from the north, to form Francia/Carolingian Empire (from 481, divided in 843).

- Lombards, who inhabited the Kingdom of the Lombards (568–774), which covered much of the Italian Peninsula.

- Suebi, who inhabited the Iberian Kingdom of the Suebi (409–585).

- Frisii, who inhabited the Frisian Kingdom (c. 600–734) near the North Sea.

Other West Germanic peoples included: Chatti/Hessians (who inhabited Hesse in Roman times); Alemanni (who inhabited Alamannia/Swabia); Bavarii (who inhabited Bavaria); and Thuringii (who inhabited Thuringia).

East Germanic peoples included, most importantly, Vandals, Goths, and Burgundians:

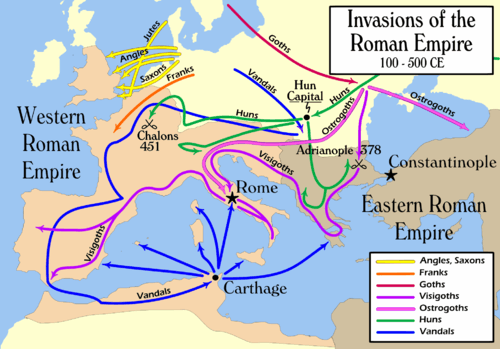

- Vandals (an East Germanic people) spread across Western Europe, Iberia, Carthage, and across the Mediterranean Sea to Rome; the Vandal Kingdom (435–534) included North Africa and Carthage; Corsica; Sardinia; Sicily. Eventually fell to the Byzantines.

- Goths (an East Germanic people) included Visigoths and Ostrogoths. Visigoths spread across the Balkan Peninsula, Italy, Rome, southern France; the Visigothic Kingdom (418–c. 720) included much of Iberia and southern France. Eventually fell to Islam, Asturias and Francia. Ostrogoths spread across Europe to Rome to form the Ostrogothic Kingdom (493–553), of Italy and the west Balkans, after the murder of Odoacer. Eventually fell to the Byzantines and the Avar Khaganate.

- Burgundians (an East Germanic people) formed the Kingdom of the Burgundians/Burgundy (411–534), before falling to the Franks.

Other East Germanic peoples and territories included: Gepids (and the Kingdom of the Gepids); and Rugii (and Rugiland).

North Germanic peoples included: Danes, Swedes, Geats, Gutes and Norsemen.

- Danes: inhabited the province of Scania, now in southern Sweden.

- Geats (Götar) and Swedes (Svear) were north of the Danes; Gutes (Gutar) inhabited the island of Gotland. They would gave rise to modern Swedes. The Geats may have given rise to the Goths.

- Norsemen (also called Norwegians) inhabited the petty kingdoms of Norway.

Non-Germanic peoples

Indo-European speaking peoples, other than Germanic peoples, included:

- Greco-Romans, who ruled the Byzantine Empire, and who spoke Ancient Greek (a Hellenic language) and Latin (an Italic language).

- Celts: were once widespread across Europe, but by the 5th century CE they had been mostly conquered. Celtic Britons inhabited England and Wales, and also Brittany. Celtic Gaels (also know as Scoti) inhabited Ireland and later Scotland. Picts (who may have been Celtic) inhabited Scotland. Other Celtic peoples included Gauls (of Gaul, present day France); Celtiberians (of Iberia); and Galatians (of ancient Anatolia). Britain was abandoned by its Roman garrison in AD 410, paving the way for Anglo-Saxon invasions from the east.

- Slavs: could be divided into North Slavs (which includes East and West Slavs); and South Slavs. West Slavs would settle in Eastern Europe areas south of the Baltic Sea. East Slavs would settle in areas that correspond to present-day Belarus, central and northern Ukraine, and parts of western Russia. South Slavs would settle in the Balkans. Early Slavic kingdoms included Samo's Empire (631–658) and Carantania (658–828).

- Balts, lived near the Baltic Sea, and are related to Slavs. Peoples included the Lithuanians, Latvians, and Old Prussians.

- Iranians: included the Eastern Iranian Alans and Pashtuns (ethnic Afghans); in the Middle East there were the Western Iranian Persians and Kurds.

Apart from the Indo-European speakers, Europe included:

- Turkic peoples: they may have included Huns; early Turkic peoples included Khazars and Bulgars. Also see the section Turkic migration.

- Uralic peoples: included Magyars (of the Principality of Hungary), Sami (of northern Scandinavia), and Finns (of Finland); related to the Finns were the Livonians (Latgalians) and Estonians.

- Northeast Caucasian people: Pannonian Avars would form the Avar Khaganate in the 6th century, before falling to the Bulgars.

- Afroasiatic peoples: Berbers (of North Africa) and Arabs (of Arabia) would latter press north into Iberia, and would be known as Moors.

Roman Empire and movements of peoples

.jpg)

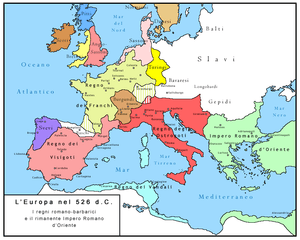

The Fall of the Western Roman Empire, in AD 476, when non-Roman Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustulus and became King of Italy (476–493). Later on it became part of the Ostrogothic Kingdom (493–553), before Italy fell to the Byzantines. The fall of Rome can in part be attributed to the migration of peoples, mainly from the east. The Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire, survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Migration Period and other migrations

Migration Period (c. AD 375 to 538): was a period of barbarian invasions of Europe. Invasions by the Huns, and also Avars, Slavs and Bulgars, caused movements in Germanic peoples, particularly Goths (including the Visigoths and the Ostrogoths), Vandals, Anglo-Saxons, and Franks. Other Germanic peoples affected included Lombards, Burgundians, Suebi, Frisii, and Alemanni.

Turkic migration: between the between the 6th and 11th centuries, there was an expansion of Turkic tribes over Asia and Eastern Europe. Early Turkic peoples in Europe were mainly Oghurs, such as Khazars and Bulgars. Later on Turks (from the Oghuz branch) and Tatars (mainly from the Kipchak branch) became prominent. Today Turkic peoples are mainly represented by Turks, Azerbaijanis and Turkmen (from the Oghuz branch); Uzbeks and Uyghurs (from the Karluk branch); and Kazakhs and Tatars (from the Kipchak branch).

Huns may have been Turkic: the Hunnic Empire (370s–469) included much of Eastern Europe and western Asia, and was unified under Attila.

Viking Age (793–1066): began with the raid on Lindisfarne (793). Vikings were North Germanic peoples, which included Danes, Swedes, and Norsemen (Norwegians). In this period they settled in Greenland, Newfoundland, and present-day Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Normandy, Scotland, England, Ireland, Isle of Man, the Netherlands, Germany, Ukraine, Russia, and Turkey. The Varangians (also known as Rus') were Viking Swedes that traveled along the Volga and Dnieper rivers, and may have founded Kievan Rus', an early Russian federation.

Vikings would give rise to Normans, descendants of Vikings who settled in Normandy, and would conquer England and south Italy in the High Middle Ages.

Other movement of peoples included Magyars, Moors (Arabs and Berbers), and Mongols (during the 13th century).

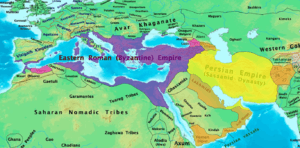

Byzantine Empire

Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire (395–1453), continued after the fall of the West. Crises of third century had led to the Roman Empire divisions of east and west. In AD 330, Constantine moved the seat of the Empire from Nicomedia to Constantinople (formerly called Byzantium, later called Istanbul), which was sometimes characterised as the "New Rome". Theodosius I (379–395) was the last Emperor to rule both East and West. The empire was oriented towards Greek rather than Latin culture, and characterised by Orthodox Christianity.

Under the Justinian Dynasty (518–602), the Byzantine Empire reached its greatest extent since the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The expansion resulted largely from the Wars of Justinian the Great (Justinian I), who ruled between 527–565, and expanded it over North Africa, southern Spain, and Italy (including Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica). It also included the Balkan peninsula, Anatolia, and the Holy Land. In this period, the Plague of Justinian (541–542 AD) had a profound effect on the population of the empire, with an estimated 25–50 million deaths.

Many territories were later lost to the Islamic Caliphates during the early Muslim conquests (622–750). The Byzantine Empire had been weakened by the ongoing Byzantine–Sasanian wars (285 to c. 628), against the Persian Sasanian Empire; this included the 626 siege of Constantinople. The Sasanian Empire itself was toppled in 651 by the Rashidun Caliphate. But at the first and second Arab sieges of Constantinople, 674–678 and 717–718, the Umayyad Caliphate was defeated by the Byzantine Empire.

Italian Peninsula in the Early Middle Ages

Odoacer's Kingdom Of Italy (476-493), which included some surrounding territory, had been conquered to form the Ostrogothic Kingdom (493–553). Theodoric the Great was the King of the Ostrogoths 475 to 526; would rule the Ostrogoths of Italy, but he would also rule the Visigoths. Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily became part of the Vandal Kingdom (435–534), along with some of North Africa and Carthage. Both the Ostrogothic and Vandal kingdoms were conquered by the Byzantine Empire under Justinian I (527–565), after the Gothic War (535–554) and the Vandalic War (533–534); and Italy and surrounding islands became part of the Byzantine Empire under the Justinian dynasty (518–602).

Starting in the 6th century, much of Italy was eventually conquered by Lombards (a West Germanic people), their Kingdom of the Lombards being at its greatest extent around 749–756. They conquered territories from the Byzantine Empire, who in the 8th century remained in the southern extremes, the territory around Rome, Sicily and Sardinia. The Kingdom of the Lombards included:

- Langobardia Major, which was the northern Lombards, which included (i) Neustria (in the north-west, later called Lombardy); (ii) Austria (in the north-east, later called the March of Verona); and (iii) Tuscia (south of Neustria, later called Tuscany).

- Langobardia Minor, which was the central and southern Lombards, which included the Duchies of Spoleto and Benevento.

Charlemagne (of Francia) conquered the northern Lombard Kingdom in 774, but never took Benevento. Venice and the Papal States were also to remain independent of Francia. In the 9th century, Moors captured Sicily from the Byzantines, to form the Muslim Emirate of Sicily (831–1091).

Later on, Normans would conquer southern Italy and Sicily between 999 and 1139. Roger II of Sicily consolidated the Norman Italian kingdoms into one, the Kingdom of Sicily, which included Sicily, southern Italy and some of north Africa. The Norman kingdom fell in 1194 to the House of Hohenstaufen, and to Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1198.

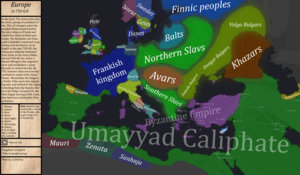

Francia and the Carolingian Empire

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks and Frankish Empire, grew from 481 onwards as the Franks were united by Clovis I (who ruled c. 481–511). Clovis was a member of the Merovingian dynasty of Frankish kings, between 450 and 751. The Battle of Tours (732) in Aquitaine, where the Franks defeated the Umayyad Caliphate, helped to establish Frankish dominance. Charles Martel commanded the Franks at Tours, and established the Carolingian dynasty of Frankish kings.

On Christmas Day in 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne (Charles I, the Great) Holy Roman Emperor, as a revival of the Western Roman Emperor. Charlemagne was King of Francia 768–814; King of the Lombards 774–814; and Emperor 800–814. As Charlemagne was a member of the Carolingian dynasty, Francia from 800 is known as the Carolingian Empire.

Charlemagne expanded the kingdom into Bavaria/Carinthia, and Lombard, Saxon and Spanish March territories. Francia by 800 covered much of the former Western Roman Empire, with most of Western and Central Europe; but not including Iberia, Britain, Jutland, Brittany, southern Italy, Venice and the Papal States. Sometimes considered to be the first Holy Roman Empire, but more often called the Carolingian Empire, and it was distinct from the Holy Roman Empire of 962–1806.

Charlemagne was succeeded as Holy Roman Emperor by his son Louis the Pious (813–840). On the death of Louis, civil war erupted (840–43), followed by the Treaty of Verdun; Francia was then divided among the three surviving sons of Louis the Pious:

- West Francia was first ruled by Charles the Bald (who later became Holy Roman Emperor and King of Italy). West Francia is considered to be the Kingdom of France with the rule of the Capetian dynasty (987 onwards).

- Middle Francia was ruled by Lothair I (who was Holy Roman Emperor); it was a short lived state of territory between West and East Francia.

- East Francia was first ruled by Louis the German; it had four stem duchies at the time: Swabia/Alamannia; Franconia; Saxony; and Bavaria (with Carinthia). East Francia would later form the nucleus of the Holy Roman Empire (962–1806) founded by Otto the Great.

With the Treaty of Prüm (855), the sons of Lothair I divided Middle Francia into:

- Lotharingia, which would later became Lorraine and Upper Burgundy, ruled by Lothair II.

- Provence, also known as Lower Burgundy, ruled by Charles of Provence.

- Italy, the northern peninsula, ruled by Louis II of Italy.

By the time of the Treaty of Meerssen (870), Charles of Provence and Lothair II had both died, and Francia had become:

- West Francia, which contained parts of Lotharingia, and some of Provence; ruled by Charles the Bald at that time.

- East Francia, which contained most of Lotharingia; ruled by Louis the German at that time.

- Italy, the northern peninsula, which had expanded to include most of Provence; ruled by Louis II of Italy at that time.

With the Treaty of Ribemont (880), some Lotharingia territory was returned to East Francia from West Francia. Francia was reunited briefly, between 884–887, under Charles III (the Fat), Emperor between 881–888; after that it then divided again. Charles was the last of the Carolingian dynasty of Holy Roman Emperors, with the exception of the disputed Holy Roman Emperor Arnulph (896–899).

Europe from 814

After the death of Charlemagne (814), Europe during the Early Middle Ages included the following states:

- British Isles

- Alfred the Great, the Anglo-Saxon King of the West Saxons, defeated the Great Heathen Army of the Danish King Guthrum at the Battle of Edington (878) to become first unified King of the Anglo-Saxons. The House of Wessex, which included Alfred, would eventually conquer all of England from the Danes under Æthelstan (c. 927). But there were also Danish kings after this, including Cnut the Great, who reigned over England 1016–1035, as well as Denmark and Norway, as the North Sea Empire. Other tribes of the British Isles included the Welsh and West Welsh (who were Celtic Britons); the Picts; and the Celtic Gaels/Scoti.

- Scandinavia and to the east

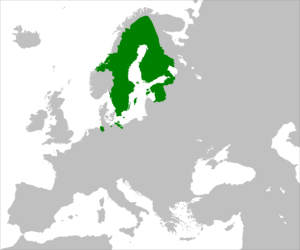

- Scandinavia was inhabited by North Germanic peoples, with Danes (in Jutland and Scania), Swedes, Geats, and Gutes. In the Unification of Norway (860s–1020s), the Norwegian Norsemen unified from the petty kingdoms of Norway. Lands of Finns (a Uralic people) lay to the east.

- Western and Central Europe

- Was dominated by Francia (with West Germanic Franks), which remained undivided until 840. Brittany was inhabited by Celtic Britons.

- Slavic states and Balts

- Included Bohemia, with West-Slavic Bohemians, the ancestors of Czechs. Great Moravia (833–c. 907) was a short lived state of the West-Slavic Moravians. Kievan Rus' principalities (882–1240) would form from East Slavic peoples, Finns and Vikings. Serbia (with South-Slavic Serbs) existed as a state between 8th century up to 1371, and then fell to the Ottomans. The Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102) of South-Slavic Croats, developed from the earlier Duchy, and would enter personal union with Hungary in 1102. Carantania (658–828) was a South-Slavic state. The Bulgarian Empire was partly South Slavic. Balts lived near the Baltic Sea, and may have ruled the territory of the Aesti (Esthland or Estonia).

- First Bulgarian Empire (681–1018)

- The First Bulgarian Empire was established by Bulgars (a Turkic people) after defeating the Byzantines at the Battle of Ongal (680); earlier Bulgar nations included Old Great Bulgaria (632–668). After defeating the Byzantines at the Battle of Achelous (917) it achieved hegemony over much of the Balkans. It was eventually subjugated by the Byzantine Empire. Much later on in the High Middle Ages, the Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396) was established after uprisings, which eventually fell to the Ottomans.

- Carpathian Basin

- In the Carpathian Basin (or Pannonian Basin), the Avars (a North-east Caucasian people) would form the Avar Khaganate (567–after 822). After being conquered by East Francia and the First Bulgarian Empire, the Magyars (a Uralic people) would establish the Principality (later Kingdom) of Hungary (895–1301).

- Iberian Peninsula

- Included the Islamic Emirate (later Caliphate) of Córdoba in southern Iberia. In the north was the Kingdom of Asturias (718–924, named after the Celtic Astures), which took over Galicia. Later on the Kingdom of Navarre, at first called Pamplona, was traditionally founded in 824; and Asturias would become the Kingdom of León (910–1230).

- Italian Peninsula

- Francia dominated the northern peninsula, and had hegemony over the Papal States. The Republic of Venice (697–1797) was within the Byzantine sphere of influence. Benevento (571–1077) was ruled by the Lombards, with the Byzantine Empire in the south. Later on the Moors would conquer Sicily from the Byzantines, and the Normans would then conquer Sicily and southern Italy.

- Byzantine Empire and to the east

- The Byzantine Empire ruled the southern Balkans and Anatolia. East of the Byzantines was ruled by the Abbasid Caliphate. Khazars (a Turkic people) and Magyars ruled Europe north of the Black Sea.

Islam and the Caliphates

Islam is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion: the central message is that there is only one God (called Allah), and that Muhammad is his prophet, whose scriptures called the Quran are the word of God; later teachings, called the sunnah, are composed of hadiths (sayings). Followers are usually called Muslims.

Shia–Sunni divide: soon after the death of Muhammad, the Muslims were divided into Shia and Sunni branches. Shias (also called Shi'ites) believed that the early caliphs should only have been members of Muhammad's family; so they only recognise the imams as being legitimate. The Battle of Karbala (680), where the supporters and relatives of Husayn ibn Ali (Muhammad's grandson and Shia imam), were defeated by a larger force of the caliph Yazid I (of the Sunni Umayyad caliphate), solidified the Shia-Sunni split. The Shias were instrumental in the Abbasid Revolution (747–750), the overthrow of the Umayyads by the Abbasids. Today the majority of Muslims are Sunni, with Shia majorities only in Iran, Iraq, Bahrain, Lebanon, and Azerbaijan.

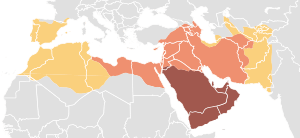

A caliphate is a state under the leadership of a caliph, an Islamic steward who claims to be a successor to Muhammad. Islamic rulers also include sultans (who rule over sultanates), and emirs (who rule over emirates). There were four main caliphates post Muhammad (who lived c. 570 to 632):

- Rashidun Caliphate (632–661), with early Muslim conquests, including the conquest of the neo-Persian Sasanian Empire.

- Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), with early Muslim conquests, including the conquest of Hispania (al-Andalus).

- Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258), and the Islamic Golden Age.

- Ottoman Caliphate (1517–1924), a later caliphate of the Ottoman Empire (1299–1922), an empire of the Late Middle Ages and modern period.

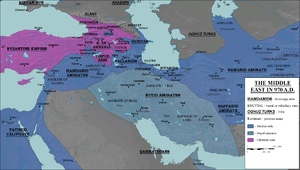

Early Muslim conquests (622–750): Muhammad, between 622 and 632, captured much of Arabia. Under the Rashidun Caliphate the Muslim conquest of Persia from the Sasanian Empire occurred, as well as conquering some lands of the Byzantine Empire. The Umayyad Caliphate, founded by Muawiyah I, greatly expanded the empire, particularly over North Africa, Iberia, and east of Persia, including some lands of the Byzantine Empire.

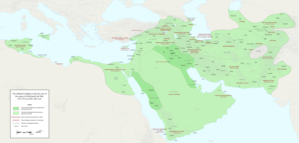

Islamic Golden Age

.png)

The Islamic Golden Age occurred during the time of the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258), a Sunni caliphate that succeeded the Umayyad Caliphate; for many years they ruled from the city of Baghdad. Early splinter states included:

- Córdoba (756–1031): the Umayyads held on to al-Andalus (Iberia) as the Emirate of Córdoba, which became a caliphate in 939. It then split into smaller states called taifas, and was later ruled by the Almoravid dynasty and Almohad Caliphate. The Reconquista was the reconquest of Iberia by Christians.

- Smaller dynasties, such as the Idrisids (788–974) who gained Morocco, and the Aghlabids (800–909) who gained Ifriqiya (north-central Africa).

During the Islamic Golden Age, science, economic development and cultural works flourished in the Middle East, with Baghdad as a central hub. The translation movement continued, which was the translation of texts into Arabic, especially from Persian and Greek. Great scholars of the Islamic Golden Age include:

- Al-Khwarizmi was a Persian scholar who made great advances in algebra, the Arabic being "al-jabr". He also developed and popularized Hindu–Arabic numerals.

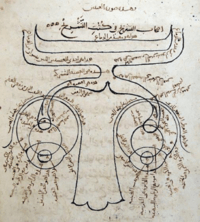

- Ibn al-Haytham was an Arab scholar described as the "father of modern optics"; he was the first to describe sight as light reflecting from an object and then entering the eyes.

- Jabir ibn Hayyan was known as the "father of chemistry", making advances in alchemy, cosmology, numerology, astrology, medicine, magic, mysticism and philosophy.

- Ibn al-Nafis was an Arab physician who first to described the pulmonary circulation of the blood.

- Avicenna (Ibn Sina) was a Persian polymath who wrote the hugely influential The Canon of Medicine and The Book of Healing.

- Al-Zahrawi was an Arab physician, surgeon and chemist, and is considered as the "father of surgery". He described over 200 surgical instruments, and used catgut for internal stitching.

- Al-Razi was a Persian polymath and physician, and an early proponent of experimental medicine.

- Omar Khayyam was a Persian mathematician, astronomer, and poet, who devised a very accurate solar calendar.

- Ismail al-Jazari was an Arab polymath who wrote The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, describing many mechanical devices.

- Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Al-Battani greatly advanced trigonometry.

By about 892 and the death of Al-Mu'tamid, the Abbasid's direct rule was reduced mostly to Mesopotamia and western Arabia, with other autonomous rulers adhering to nominal Abbasid suzerainty. Later on Abbasid political power would further diminish, especially with the rise of the Iranian Buyids and Seljuk Turks. But the Abbasids would be recognized as caliphs by most dynasties that followed, and there were also later political revivals.

Islam during the ninth and tenth centuries

Arab and Berber dynasties included the Abbasids, but the Hamdanid dynasty and Fatimid Caliphate would also gain prominence:

- Hamdanid dynasty (890–1004) was a Shia Muslim Arab dynasty of northern Mesopotamia and Syria. It would fall to the Uqaylid dynasty (990–1096), a Shia Arab dynasty.

- Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171) was an Arab and Berber Caliphate of the Isma'ili-Shia. Starting in North Africa and Sicily, it spread to Egypt, the Holy Land, and western Arabia. It was eventually reduced mostly to Egypt, and would later be taken over by the Ayyubid dynasty.

The "Shia Century" was the period of vitality by Shia Muslim dynasties starting in the tenth century, such as the Hamdanids, Uqaylids, Fatimids, and Buyids; although many Iranian dynasties were Sunni Islam. It ended with the "Sunni Revival", with the rise of Turkic dynasties of Sunni Islam.

The Iranian Intermezzo was an interlude of ethnic Iranian dynasties (mainly Persians and Kurds), between the dominance of the Arab and Berber dynasties in the Middle East, and the rise of Turkic dynasties:

- Buyid dynasty (934–1062) was a Shia Iranian dynasty, which would rule lands in Mesopotamia and Persia during this time.

- Other Iranian dynasties tended to be more Sunni Islam, and included the Samanids (819–999), Tahirids (821–873), Saffarids (861–1003), Sajids (889–929), Ziyarids (930–1090), and Sallarids (942–979).

Turkic dynasties, of Sunni Islam, ended the Iranian Intermezzo, such as the Ghaznavids, Seljuk Turks, and Khwarazmians.

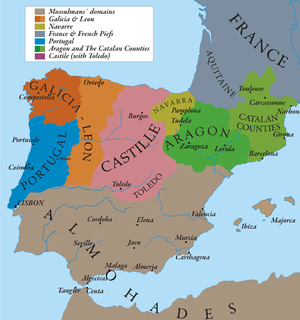

Reconquista

The Umayyad conquest of Hispania (711–788) was the capture of Iberia by the Umayyad Caliphate from the Visigoths, who by 624 had gained control of all of Iberia. Hispania was the Roman name for Iberia, which is now Spain and Portugal. The Islamic dominions of Iberia were known as al-Andalus; they were ruled by Muslim Arabs and Berbers known as Moors. The Emirate of Córdoba (756–939) was a splinter state ruled by the Umayyads, after al-Andalus separated from the Abbasid Caliphate. Córdoba would later became a caliphate (939–1031), before splitting into many independent states, called taifas.

The Reconquista was the reconquest of Iberia by Christians, began after the Battle of Covadonga (either 718 or 722), where the Visigoth Pelagius of Asturias defeated the Moors. The Christian Kingdom of Asturias was founded after it. The Franks were successful in early battles against the Moors; at the Battle of Tours (732), also known as the Battle of Poitiers, the Frankish leader Charles Martel defeated the Umayyad Caliphate. After Barcelona was conquered by the Moors, the city was retaken by Franks, led by Louis the Pious, in 801. Almanzor, the Umayyad vizier between 978 and 1002, waged many campaigns against the northern Christian kingdoms.

Alfonso III of Asturias (866–910) would consolidate power and have numerous victories over Islamic and Christian opponents. It is assumed that the old Asturian kingdom was divided between the three sons of Alfonso III of Asturias, into the kingdoms of León, Asturias and Galicia. The Kingdom of León was so named as the capital was shifted from the city of Oviedo to the city of León in 910. The Kingdom of León would unite with the Kingdom of Asturias in 924; and the Kingdom of León would at times be in personal union with the Kingdom of Galicia, with this becoming permanent with the Crown of Castile of 1230 to 1715.

Iberia during the High Middle Ages

During the High Middle Ages, Al-Andalus (that is, Islamic Iberia) rulers would include the Almoravid dynasty (1040–1147), and Almohad Caliphate (1121–1269).

During the High Middle Ages, the Kingdom of León would give rise to two new kingdoms:

- Kingdom of Castile (1065–1230): in 931 the County of Castile separated from the Kingdom of León; Castile became a kingdom in 1065. Between 1037 and 1065, and 1072 and 1157, Castile and León would be in personal union. With the Crown of Castile of 1230 to 1715, Castile and León and would be permanently united. With Castile and León, the crown would eventually unite the kingdoms of Galicia, Toledo, Seville, Córdoba, Jaén, Murcia, Granada, and Navarre; and the Principality of Asturias and Lordship of Biscay.

- Kingdom of Portugal (1139–1910): the County of Portugal (1093–1139), in 1128 with the Battle of São Mamede, achieved independence from the Kingdom of León, and then became a kingdom.

The Kingdom of Navarre, traditionally founded in 824 as the Kingdom of Pamplona, was a northern Basque-based kingdom. Sancho III of Pamplona was King of Pamplona/Navarre (1004–1035); he gained suzerainty of many lands, including the counties of Aragon, Castile and Barcelona, as well as León and the French Duchy of Gascony. His son Ferdinand I of León would rule both Castile and León; his other sons were García Sánchez III of Pamplona, and Gonzalo of Sobrarbe and Ribagorza, and Ramiro I of Aragon.

The County of Aragon would become the Kingdom of Aragon (1035–1707), first ruled by Ramiro I; later the Crown of Aragon (1162–1716) would be result from the Union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of Barcelona, El Cid (Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar) took Valencia from Muslims in 1094; it would later be retaken by Muslims before being conquered by Aragon.

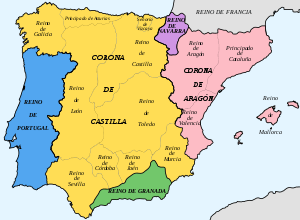

After the Siege of Córdoba (1236) and Siege of Seville (1247-1248), the cities fell to Castile. By 1250 only the Emirate of Granada remained Islamic; the northern Christian states consisted of the crowns of Castile and Aragon, and the kingdoms of Portugal and Navarre.

Iberia during the Late Middle Ages

King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile were later called the Catholic Monarchs; they were both from the House of Trastámara, and their marriage in 1469 marked the de facto unification of Spain (as Aragon and Castile). In 1478, Ferdinand and Isabella launched the Spanish Inquisition primarily to identify heretics, especially among the conversos, those who converted to Catholicism from Judaism and Islam; Tomás de Torquemada was the first Grand Inquisitor between 1483 and 1498.

Ferdinand and Isabella completed the Reconquista with a victorious war against the Emirate of Granada (1482–1492). After the Reconquista, the Alhambra Decree (1492) led to the expulsion of Jews from Spain, although Jews who converted to Christianity escaped expulsion. It was followed by forced conversions and expulsions of Muslims; even some Moriscos (i.e. Muslims who had converted to Christianity) experienced expulsion.

In 1512, most of the Kingdom of Navarre was annexed to the Crown of Castile. In 1519 the crowns of Aragon and Castile would join in personal union with Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and from then onwards they remained in personal union, finally becoming a unified crown of Spain in 1715. But Portugal would remain independent of Spain, except for the period of the Iberian Union (1580-1640).

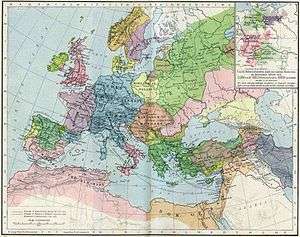

Chapter 2 High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages was circa AD 1000–1300, or 1000–1250.

See also Wikipedia:High Middle Ages.

States and territories of the High Middle Ages

States and territories of the High Middle Ages included:

- Northern Europe

- Britain Isles included England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. Nordic countries included Norway, Denmark, and Sweden, and lands of the Sami and Finns. Valdemar I of Denmark saw his country becoming a leading force in northern Europe.

- Western and Central Europe

- Consisted of the Kingdom of France and the Holy Roman Empire.

- Eastern Europe

- In the Kingdom of Poland (1025–1569), Casimir III of Poland doubled the size of kingdom by the end of his reign (1333–1370) and considerably strengthened the nation. Around the Baltic Sea there were Finnic Estonians and Livonians; and Baltic Tribes, composed of Balts, including Old Prussians, Lithuanians, and Latvians. Further east was Kievan Rus' (882–1240; founded by the Rus' people), and the Novgorod Republic (1136–1478). The Balkans were dominated by five states: Hungary (which gained hegemony over Croatia, Bosnia, Slavonia, Dalmatia and Transylvania); Grand Principality of Serbia (1091–1217, which expanded over what is today Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and southern Dalmatia); the Second Bulgarian Empire; and the Byzantine Empire (which included Greece and some of Anatolia); and the Cuman-Kipchak confederation (a Turkic state also known as Cumania, of the 10th century to 1241).

- Iberian Peninsula

- Included the Christian kingdoms of Castile, León, Navarre, Aragon, Portugal. The Muslim Caliphate of Córdoba was, after 1031, replaced by taifa (independent Muslim states). The Reconquista (722–1492) was the reconquest of Iberia by Christians.

- Italian Peninsula

- Included the Kingdom of Sicily, which was under Norman rule from 1091, which included southern Italy by 1130. The Republic of Venice, Papal States, and the Holy Roman Empire were in the north.

Normans

Normans: came from Normandy, a northern region of France, and were descended from Vikings and indigenous Gallo-Romans and Franks. They gained gained political legitimacy in 911 when the Viking leader Rollo agreed to swear allegiance to King Charles III of West Francia, in exchange for ceding them lands. Culturally, they were known for their Norman architecture (also known as Romanesque architecture); they adopted a Gallo-Romance language called Norman French.

From the 11th century onwards they conquered the Kingdom of England, and the Kingdom of Sicily (which was mainly in southern Italy and Sicily), as well as other territories, including in the Middle East. The Norman conquest of England, under William the Conqueror, began with the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Later on their influence would spread to the rest of the British Isles (Wales, Scotland, and Ireland).

The Kingdom of Sicily (1130–1816) was formed, between 999 and 1139, as a Norman kingdom in southern Italy, Sicily, northern Africa and Malta. Conquered territories in southern Italy included (based on Italy at around 1000 AD): territory held by the Byzantine Empire (roughly modern day Calabria and Apulia); Salerno (roughly Basilicata); Benevento (except for the city); Capua; Amalfi; the southern region of Spoleto; and the Muslim-held Emirate of Sicily. Later on southern Italy would cede from Sicily to form the Kingdom of Naples (1282–1816).

England and the Angevin Empire

After the Norman conquest of England, which began with the Battle of Hastings (1066), England was ruled by the House of Normandy; the reign of William the Conqueror (1066–1087), was followed by that of his sons William II (1087–1100) and Henry I (1100–1135). But after the death of Henry I, a succession crisis between the Empress Matilda (Henry I's daughter), and Stephen of Blois (Henry I's nephew), brought about the Anarchy (1135–1153), a period of civil war between the claimants. The Anarchy was ended by the Treaty of Wallingford (1153), where Stephen recognized Matilda's son Henry II as heir to the crown.

King Henry II (who reigned 1154–1189) was the first of the Plantagenet dynasty of English kings (1154–1485), named after his father Geoffrey Plantagenet, the Count of Anjou. Henry II would inherit the following titles:

- King of England, from his mother's claim, the Empress Matilda

- Duke of Normandy, and Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine, from his father

- Duke of Aquitaine, from his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, Duchess of Aquitaine

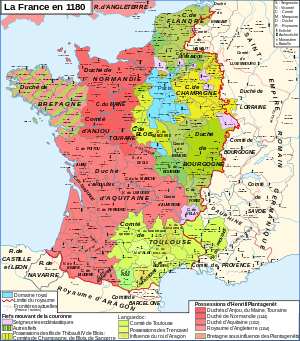

Henry II also partially controlled the Duchy of Brittany, as well as Scotland and Wales. After the Norman invasion of Ireland (1169–1171), Henry II became Lord of Ireland. Henry II's empire became known as the Angevin Empire (1154–1214), named after the county of Anjou. The Angevin kings of England were the kings who ruled the Angevin Empire, the first three Plantagenets: Henry II, and his sons King Richard I (Richard the Lionheart) and King John. As well as the Angevin Empire, France consisted of the domaine royal (directly controlled by the king), ecclesiastical lordships, and various other fiefs (including those of the Languedoc province).

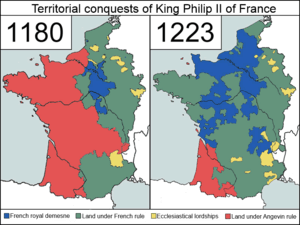

Capetian–Plantagenet rivalry (1159-1259), between the French House of Capet and the English House of Plantagenet, resulted from the Angevin Empire, and a series of wars over the territory is sometimes considered to be the "First Hundred Years War". King John (who reigned 1199–1216) lost control of most of his French possessions to King Philip II of France (Philippe Auguste), who reigned 1180 to 1223. It included the successful French invasion of Normandy (1202–1204). The Anglo-French War of 1213 to 1214 culminated in French victory against the Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV at the Battle of Bouvines, who had allied with the English. Only Gascony in southern Aquitaine would remain English.

The Magna Carta ("Great Charter") was then forced upon John by the English barons; it guaranteed certain rights, and was agreed at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. This was followed by the First Barons' War (1215–1217), after John reneged on the Great Charter, which he had annulled by Pope Innocent III. The future Louis VIII of France (the son of Philip II) backed the rebellious barons, and claimed the English throne between 1216 and 1217. In 1216 John was succeeded by his son Henry III, who reissued a modified Great Charter in 1216 to try to appease the barons; Louis was eventually defeated as the barons defected to Henry III. Great Charters were also issued in 1217, 1225, and 1297.

Henry III was succeeded by his son Edward I (also called Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots); and then by his son Edward II (also called Edward of Carnarvon). Power was wrestled from Edward II by his son Edward III (1327–1377), backed by Edward III's mother Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer. During the reign of Edward III, the loss of Gascony (1337), and Edward's rival claim to the French crown, triggered the Hundred Years' War.

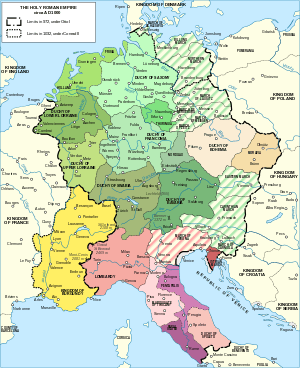

Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire (962–1806), of Emperor Otto I the Great, was a union of East Francia and Italy. Otto was a Saxon, and Duke of Saxony and King of East Francia from 936; King of Italy from 961; and Holy Roman Emperor between 962–973, after a large interregnum (gap) between 924–962 (38 years). The Nazis considered it to be the first German Reich (Deutsches Reich), where reich is roughly comparable to "realm". Before their coronation as emperors, or as heir-apparents, their rulers were designated as kings, most commonly as "King of the Romans".

By 947, the former Francia had divided into four kingdoms: West Francia; East Francia; Kingdom of Italy; Kingdom of Arles. East Francia and the Kingdom of Italy initially formed the Holy Roman Empire; later on Bohemia (which was never part of Francia) and the Kingdom of Arles joined. West Francia would go on to form the Kingdom of France.

- 1. East Francia by 962 had six stem duchies: (i) Franconia; (ii) Swabia (former Alamannia); (iii) Saxony; (iv) Bavaria; (v) Upper Lorraine (in south); (vi) Lower Lorraine (in north). It remained the centre of the Holy Roman Empire for its lifetime, and is sometimes considered as the Kingdom of Germany.

- 2. The Kingdom of Italy was roughly the Italian Republic north. At about 1000 it included Lombardy, the March of Verona and Aquileia, the March of Tuscany, and the Duchy of Spoleto; but excluded Venice and the Papal States. Holy Roman Emperors were also kings of Italy between 962–1493 and 1519–1556 (Charles V). After that Italy was nominally within the Holy Roman Empire until 1801, but power was lost.

Later territories gained by Holy Roman Empire (East Francia and Italy) were Bohemia and the Kingdom of Arles:

- 3. Duchy/Kingdom of Bohemia, a Holy Roman Empire state between 1002–1806. Now roughly the Czech Republic (with Moravia and Silesia). Raised to a kingdom between 1198–1918; sometimes the Emperor was also king.

- 4. Kingdom of Arles/Arelat of 933–1378; part of the Holy Roman Empire between 1032–1378. The Kingdom of Upper Burgundy established from 888, was composed of Transjurania and the County of Burgundy. The Kingdom of Lower Burgundy, which was composed of Cisjurania and Provence, joined in 933 to form Arles. Now partly Swiss, French and Italian. Distinct from the French Duchy of Burgundy, which was a separate territory.

Also, the Kingdom of Sicily (of southern Italy and Sicily) was in personal union with the Holy Roman Empire between 1194–1254.

The Holy Roman Empire achieved its greatest extent during the Hohenstaufen dynasty of kings, who were emperors between 1155–1250, except for 1198–1215. Frederick I Barbarossa (Emperor 1155–1190) held great power, despite defeats by the Lombard League. But under Frederick II (Emperor 1220–1250), the rule of the emperor was weakened with the Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis ("Treaty with the princes of the church") of 1220, and the Statutum in favorem principum ("Statute in favour of the princes"), confirmed in 1232. Frederick II was also king of Sicily (1198–1250).

Later, large interregnums (gaps) of Emperors occurred between the years of 1245–1312 (67 years) and 1378–1433 (55 years). The Golden Bull of 1356 named seven Prince-electors who chose the Emperor: Archbishops of Mainz, Cologne and Trier; King of Bohemia; Count Palatine of the Rhine; Duke of Saxony-Wittenberg; Margrave of Brandenburg.

Christianity and the Great Schism

Christianity: is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the teachings of Jesus Christ as described in the New Testament. Christians, the members of the faith, believe that Jesus is the Messiah as prophesied in the Old Testament; and, apart from Nontrinitarians, that God is a Holy Trinity of the Father, the Son of God (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit. Early Christianity was from its origins (c. 30–36) until the First Council of Nicaea (325); this created the Nicene Creed and was the first ecumenical council. Constantine the Great (who reigned East 306–324, and East and West 324–337) was the first Christian Roman Emperor. By the time of the 6th century, Christianity was dominate throughout Europe, but not including northern and eastern Europe, and Scandinavia. By the time of the 11th century, the majority of Europe was Christianised, with the exception of some Baltic states and eastern Scandinavia, and Islamic Iberia.

Great Schism, or East–West Schism, of 1054: the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches separated, after the mutual excommunication of the Michael I Cerularius (the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople) and Cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida, papal legate of Pope Leo IX. There were many reasons for the schism, including doctrinal, theological, linguistic, political, and geographical reasons. A particular issue was the question of the authority of Constantinople and Rome over the other three seats of the Pentarchy; that is, Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria.

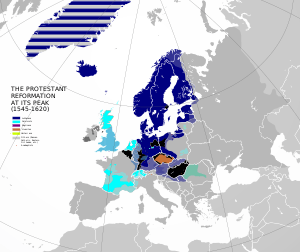

Since that time the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches have remained separate. The Roman Catholic Church consists of the western Latin Church, and 23 Eastern Catholic Churches. The Holy See is the jurisdiction of the pope, and includes the Diocese of Rome (as the Bishop of Rome), the worldwide Roman Catholic Church (as leader in full communion with), and the Vatican City state (as sovereign). During the pre-Protestant Bohemian Reformation (after the Hussite Wars, 1419–1434) and the Protestant Reformation (1517 onwards), some churches in the west seceded from the Catholics.

The present-day Eastern Orthodox church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, is a communion that includes many Orthodox churches. The Greek Orthodox Church includes the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, and the Greek Orthodox Patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem, and the Churches of Greece, Albania, Crete and Sinai. Other major Orthodox Churches include those of Russia, Ukraine, Romania, Serbia, and Bulgaria. The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople has the status of primus inter pares (first among equals) among the other Eastern Orthodox prelates (bishops and patriarchs).

Oriental Orthodoxy has been separate to Eastern Orthodoxy since the Council of Chalcedon (451), and includes churches in Alexandria (the Coptic Orthodox Church), Antioch (Syriac Orthodox), Armenia (Apostolic), India (Malankara Orthodox Syrian), and the Orthodox Tewahedo Churches of Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Islam, Crusades, and Mongol invasions

The Islamic Golden Age continued into the High Middle Ages. Although the influence of the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258) would wane, they would continue to be recognized as caliphs by most Islamic dynasties, and would survive until the Mongol invasions. The Iranian Intermezzo ended with the rise of some Islamic Turkic dynasties in the Middle East; these included:

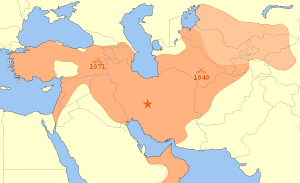

- Ghaznavid dynasty (977–1186) was a Turkic Sunni Muslim dynasty that gained territories, including from both the Iranian Samanids and Saffarids. At its greatest extent about 1030, it fell across modern-day Iran and Afghanistan, and all the way to the Indian subcontinent. It would fall mainly to the Seljuk Empire and the Ghurid dynasty.

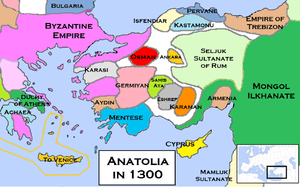

- Seljuk Empire (1037–1194) was a Turko-Persian Sunni Muslim empire, founded by the Oghuz Turkic warlord Seljuk Beig. They took lands from other dynasties, including from the Iranian Buyid dynasty and the Turkic Ghaznavid dynasty. With its greatest extent in about 1092, it covered a vast area, including Palestine, and much of Anatolia, the Levant, Persia and beyond. The Battle of Manzikert (1071) was decisive in their capture of much of Anatolia from the Byzantines.

- Seljuk Sultanate of Rum (1077–1308) was a Seljuk Turk splinter state in Anatolia. Surviving long after the Seljuk Empire, it declined after defeat by Mongols.

- Zengid dynasty (1127–1250) was a Turkic state of Sunni and Shia Islam. Originally a Seljuk Turk vassal, it continued for a while after the Seljuk Empire, before falling to the Mongols and Ayyubids.

- Khwarazmian dynasty (1077–1231) was a Persianate Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic origin, that gained much of Persia and beyond, mainly from the Seljuks and Ghurid dynasty. It ended after the Mongol conquest of Khwarezmia (1219–1221), with a heavy toll on life.

As well as the Turkic dynasties, the Ghurid dynasty (before 879–1215) was an Iranian dynasty from the Ghor region of present-day central Afghanistan, gaining its greatest extent around 1200, including territories from the Ghaznavids and Seljuks. The dynasty converted to Sunni Islam from Buddhism. It fell across modern-day Iran and Afghanistan, and the northern Indian subcontinent all the way to Bengal. It would fall mainly to the Delhi Sultanate and Khwarazmian dynasty.

At around 1200, when the Abbasid, Seljuk Rum, Khwarazmian, and Zengid dynasties were still active in the Middle East, there was two major Islamic dynasties in northern Africa:

- Ayyubid Sultanate (1171–1260), overthrew the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. Ayyub's son Saladin was their first sultan (1174–1193), a Kurdish Sunni Muslim who switched allegiance to the Abbasid caliphs. It conquered Jerusalem from the crusaders (1187) and other lands in the Middle East. They eventually fell to the Mamluk Sultanate.

- Almohad Caliphate (1147–1269) was a Moroccan Berber Sunni caliphate. It ruled much of western north Africa and southern Iberia. It was overthrown by the Marinid dynasty.

Later on there would be Islamic dynasties such as the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo, and the beginnings of the Ottoman Empire.

Crusades and crusaders

.jpg)

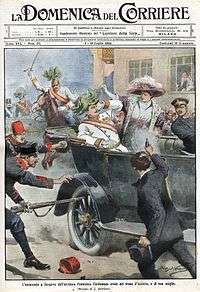

The crusades were a series of holy wars, predominantly Christians against Muslim-held territories. The immediate cause was the Byzantine–Seljuk wars (1048–1308), an ongoing conflict over Anatolia, and in 1095 the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos requested military aid from Pope Urban II; Urban II responded by calling for war against the Seljuk Turks in the Holy Land.

The crusaders opened trade routes which enabled the merchant republics of Genoa and Venice to become major economic powers. It led to the establishment of diverse religious-military orders; they included:

- Knights Templar (the Order of Solomon's Temple), who built a network of nearly 1,000 commanderies and fortifications across Europe and the Holy Land, before being disbanded by Philip IV of France and Pope Clement V

- Knights Hospitaller (the Order of Saint John), who later became knights of Cyprus, Rhodes, and Malta, and are now the Sovereign Military Order of Malta

- Teutonic Order (the German Order): formed to aid Christians on their pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and took part in the Prussian Crusade (a Northern Crusade), and merged with the Livonian Brothers of the Sword

- Livonian Brothers of the Sword: they took part in the Livonian Crusade (a Northern Crusade), and later merged with the Teutonic Order as the Livonian Order

As well as the Crusades to the Holy Land, other crusades included:

- Northern Crusades (1147–1410) were primarily against pagans, from the Baltic, Finnic and West Slavic peoples; Baltic states that resulted included the State of the Teutonic Order (Prussia) and Terra Mariana (of present day Estonia and Latvia).

- Crusades against Christians occurred between 1235 and 1434: they included the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229) against Cathars in southern France.

- Between 1291 and 1481 there were was then a number of additional crusades against Muslims that didn't target Jerusalem. There was also some anti-Muslim crusades during the Reconquista (718–1492).

Crusades to the Holy Land and Latin Empire

There were nine numbered Crusades to the Holy Land (1095–1291), but there were many additional ones. The popular crusades (1096–1320) were unsanctioned by the Church, and were minor crusades which achieved very little; they included the People's Crusade (1096), Children's Crusade (1212), Shepherds' Crusade (of 1251 and 1320), and Crusade of the Poor (1309).

The Seljuks held Jerusalem, from 1073–1098; before that it had been held by the Byzantines (to 638) and the Caliphates. After that, Jerusalem was held by the Fatimid Caliphate (1098–1099); Crusaders (1099–1187); the Ayyubid Sultanate (of Saladin), Christians and Khwarezmian Tatars (at various times between 1187 and 1260); the Mamluk Sultanate (1260–1517); the Ottoman Empire (1517–1917).

Notable crusades included:

- First Crusade (1095–1099) resulted in the conquest of Jerusalem and the Holy Land. It was preceded by the People's Crusade (1096), and followed by the Crusade of 1101 (Crusade of the Faint-Hearted), which were both Turkish victories.

Crusader states were then established, and included the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli and the County of Edessa. Nicaea and much of western Anatolia was also restored to the Byzantine Empire.

- Venetian Crusade (1122–24), in which the Republic of Venice succeeded in capturing Tyre.

- Second Crusade (1147–1149) was a failed attempt to reclaim of Edessa after its fall in 1144.

Jerusalem was retaken by Muslims led by Saladin of the Ayyubid Sultanate in 1187, reverting to Christian control in 1229.

- Third Crusade (1189–1192) included as crusaders Philip II of France, Richard I of England, and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. It failed to retake Jerusalem, but a treaty provided that unarmed Christian pilgrims and traders could visit Jerusalem. Crusader territories were reclaimed, including the key towns of Acre and Jaffa; the crusader state of the Kingdom of Cyprus was established.

- Crusade of 1197, of Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, resulted in the capture Beirut and Sidon from the Muslims in 1198.

- Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) primarily resulted in the Sack of Constantinople (1204) by crusaders and the Republic of Venice. The Catholic city of Zara was also sacked by crusaders.

After that the Byzantine Empire was partitioned: the Latin Empire of Constantinople was a crusader state, which had crusader vassal fiefs such as Thessalonica, Achaea, Athens, and the Archipelago. Venice took control of some areas, such as Crete. Greek successor states were established in Nicaea, Epirus, and Trebizond. The Nicaean–Latin wars of Nicaea and the Latin Empire commenced, and as well as the Bulgarian–Latin wars.

- Fifth Crusade (1217–1221) was an unsuccessful attempt to conquer the powerful Ayyubid state in Egypt, to later regain Jerusalem.

- Sixth Crusade (1228–1229) resulted in a diplomatic crusader victory, who gained control of Jerusalem between 1229 and 1244.

- Barons' Crusade (1239–1241) enlarged the territory controlled by the crusaders, and was in territorial terms the most successful crusade since the First.

Reconquest of Constantinople: Nicea was later able to recapture much of the Latin Empire and Epirus, including Constantinople in 1261, and the Byzantine Empire continued as a weakened Greek state. Later on a Byzantine civil war (1341–1347) further weakened the empire. Eventually Constantinople would fall to the Ottomans in 1453.

Jerusalem was lost to Khwarezmian Tatars (1244–1247), the Ayyubids (1247–1260), and the Mamluk Sultanate (1260–1517). The Seventh (1248–1254), Eighth (1270), and Ninth (1271–1272) Crusades had varying degrees of success, but didn't retake Jerusalem.

Mongol Empire

Genghis Khan founded the Mongol Empire in 1206; it eventually covered most of central Asia from the west to east. The Mongols were a group of steppe nomads. Khan is a title for a sovereign or a military ruler, used by Mongols living to the north of China. An estimated 30 to 80 million people were killed under the rule of the Mongol Empire.

By c. 1294, with the death of Kublai Khan, it had fractured into independent states:

- Golden Horde (1242–1502), a khanate in the north-west, mostly north of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea. It would disintegrate to many other khanates in the fifteenth century.

- Ilkhanate (1256–1335) a short-lived khanate in the south-west, across the Middle East and Persia.

- Chagatai Khanate (1226–1705) in central Asia, centered on present-day Kyrgyzstan. It would decline to other dynasties.

- Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) in the east, based in modern-day Beijing; it included much of present-day China and Mongolia. It would fall to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

End of the Islamic Golden Age

The Siege of Baghdad (1258) was by the Mongols under the command of Hulagu Khan. They subsequently sacked the city and destroyed the copious libraries, including the House of Wisdom; hundreds of thousands of people were killed in the region. This ended the Abbasid Caliphate and Islamic Golden Age, and the region was made part of the Mongol Empire.

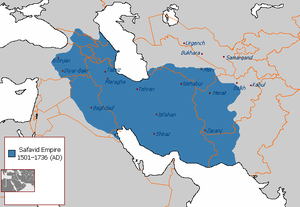

The Mongol Empire was in part succeeded by the Ilkhanate (1256–1335), the south-west sector of the Mongol Empire. In the 1330s, outbreaks of the Black Death ravaged the Ilkhanate, causing it to disintegrate. The Timurid Empire (1370–1507) was a latter large Turco-Mongol empire of the Middle East and beyond, which continued the Mongol legacy. In part it was succeeded by the Iranian Shia Muslim Safavid dynasty (1501–1736).

In Egypt and the Middle East, the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo (1261–1517), also known as the Realm of the Turks, overthrew the Ayyubids. It was an Arabic, Turkic and Circassian Sunni sultanate. With the fall of the Abbasids in 1258 and the end of the Islamic Golden Age, the Mamluks attempted to re-establish a Sunni Abbasid Caliphate with the Caliphs of Cairo; they were largely ceremonial caliphs under the patronage of the sultans. The Mamluk Sultanate eventually fell to the Ottoman Empire.

The Ottoman Empire (c. 1299–1922) was founded by Osman I of the House of Osman. Starting from a small Anatolian beylik (state), and with the decline of the Sultanate of Rum, they would go on to build a vast empire, including territories in Anatolia, eastern Europe, the Middle East, and northern Africa.

Golden Horde

Golden Horde (1242–1502), or Kipchak Khanate, was originally a Mongol, and later Turkicized, khanate founded by Batu Khan, a Mongol warlord who followed the Tengrism religion. It originated as the north-western sector of the Mongol Empire. It had a geographic area roughly comparable to the earlier Cumania (the Cuman-Kipchak confederation), a Turkic state of the Cumans and Kipchaks; and that of Volga Bulgaria, a historic Bulgar state. It was majorly divided into Blue Horde (Kok Horde) and White Horde (Ak Horde). Öz Beg Khan assumed the throne in 1313, and adopted Islam as the state religion.

With the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus' (1237–1242), the last vestiges of the state finally disintegrated, and its former principalities became Mongol vassals; there was widespread destruction, but the Novgorod Republic remained relatively unscathed. The "Tatar Yoke" is a phrase often used to express their rule, as many of the rulers became Tatars, who were Turkic peoples who adopted the Kipchak language as a common tongue. With the breakup of Kievan Rus', the East Slavic peoples would eventually evolve three separate nations: modern-day Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. Russia would develop from the rise of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, also called Muscovy.

The Golden Horde would lose control of the Rus' principalities, and then disintegrate into a number of Turkic-speaking khanates: Tyumen Khanate (1468), later Khanate of Sibir; Khanate of Kazan (1438) – Qasim Khanate (1452); Khanate of Crimea (1441); Nogai Horde (1440s); Kazakh Khanate (1465); and Khanate of Astrakhan (1466). These would all fall to Russian expansion. See also the Rise of Muscovy for more about Kievan Rus' and the rise of Muscovy.

Medieval renaissances and cultural changes

Medieval renaissances can refer to various movements in the latter half of the Early Middle Ages, and during the High Middle Ages.

- Carolingian renaissance, of the 8th and 9th centuries, was a period of renewed cultural and intellectual movements associated with the rise of the Carolingian Empire, and the Carolingian court.

- Ottonian renaissance, of the 10th and 11th centuries, was a similar phenomenon associated with the Ottonian period of the Holy Roman Empire. Otto I, Otto II and Otto III ruled the culturally Germanic empire between 936–1002, and created a revival particularly in arts and architecture.

- Renaissance of the 12th century: included social, political and economic transformations; intellectual revitalization (philosophical and scientific). It included Latin translations of Arabic sources.

In the thirteenth century, Thomas Aquinas developed scholasticism (early critical thought in a religious context) with his Summa Theologica; written between 1265 and 1274, it was a treatise on theology that drew from a wide range of philosophical sources. It attempted to reconcile the philosophy of Aristotle with the theology of Augustine of Hippo, using both reason and faith. In 1202, in his Book of Calculation, the Italian mathematician Fibonacci helped to populise Arabic numerals.

Romanesque architecture (also known as Norman architecture) dominated 11th and 12th centuries; earlier architecture was known as Pre-Romanesque. Later on Gothic architecture was used widely between the 12th and 16th centuries.

The High Middle Ages was accompanied by a rapid increase in population; this would grind to a halt in the 14th century, as Europe would enter a period of crisis.

Chapter 3 Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages was circa AD 1300–1500 or 1250–1500.

See also Wikipedia:Late Middle Ages.

States and territories of the Late Middle Ages

States and territories of the Late Middle Ages included:

- Northern Europe

- British Isles included England and Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. The Kalmar Union (1397–1523) was of the three kingdoms of Denmark, Sweden (then including most of Finland), and Norway. There were also lands of Lapps and Finns.

- Western and Central Europe

- France with Gascony (in southern Aquitaine); Gascony precipitated the Hundred Years' War when it was lost by the English. The Holy Roman Empire was east of France.

- Eastern Europe

- Included Poland (including Mazovia) and Lithuania; Galicia–Volhynia was later divided between Poland and Lithuania. The State of the Teutonic Order (Prussia) and Terra Mariana (of present day Estonia and Latvia between 1207–1561) were Baltic crusader states. Further east: the Kievan Rus' principalities were vassals of the Golden Horde khanate; there was also the Novgorod Republic (1136–1478). Balkans states: included the Kingdom of Hungary, which included the Banate of Bosnia, Croatia, and Transylvania. The Danubian Principalities (Wallachia and Moldavia) were vassals of the Hungarians; after gaining independence they would become vassals of the Ottomans. Further south were the Byzantine Empire, the Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396), the Serbian Empire, crusader states (e.g. the Duchy of Athens), and possessions of Venice and Genoa. Louis I of Hungary was was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1342 and King of Poland from 1370; he had many military successes.

- Iberian Peninsula

- Was dominated by Castile, Portugal and Aragon. It also included Navarre, the Kingdom of Majorca (the Balearic Islands), and Islamic Granada. The fall of Granada in 1492 ended the Muslim rule in Iberia.

- Italian Peninsula

- In the north was the Holy Roman Empire; but Italian city-states, such as the Republics of Genoa and Pisa, were starting to assert de facto independence, as well as expanding their territories, including Genoese Corsica. There was also the Papal States and Venice, with Venice greatly expanding its territories along the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. In the south was the Kingdom of Naples (1282–1816) and Kingdom of Sicily (1130–1816).

Crisis of the Late Middle Ages

Around 1300, centuries of prosperity and growth in Europe came to a halt, and Europe entered a state of crisis. It resulted in a reduction of the population of Europe by about 50%; but this period was also the beginnings of the Italian Renaissance. Contributors included famines and plagues, revolts, and wars.

- Famines and plagues: includes the Great Famine of 1315–1317 (due to crop failures); and the Black Death (peaking 1347 to 1351), an outbreak of the plague.

- Peasant revolts: includes the Jacquerie (1358, France); and the Peasants' Revolt (England, 1381), Wat Tyler's Rebellion.

- Wars: includes the Hundred Years' War (1337 to 1453) and Wars of the Roses (1455–1487). They also included wars from the Rise of the Ottomans (1299–1453), Mongol and Tatar raids against Kievan Rus' (1223–1480), Polish–Teutonic Wars between the Kingdom of Poland and the State of the Teutonic Order, and Burgundian Wars (1474–1477).

France

France developed from West Francia (the Kingdom of the West Franks, 843–987) formed from division of the Carolingian Empire under the Treaty of Verdun (843). From 987, France was ruled by the Capetian dynasty, beginning with Hugh Capet, Duke of France and Count of Paris. This replaced the previous Carolingian kings (936–987). The Capetian dynasty of France, until dethroned by the French First Republic, was the following:

- House of Capet (987–1328).

- Valois kings of France (1328–1589): the houses of Valois, Valois-Orléans, and Valois-Angoulême.

- House of Bourbon (1589–1792).

Burgundian State

The Duke of Burgundy was an immensely powerful figure who ruled the Burgundian State (1384–1482). As well as the French Duchy of Burgundy, they would gain control of the Free County of Burgundy and the Burgundian Netherlands, as well as other lands. The Burgundian Netherlands roughly covered the present-day Low Countries (Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg). The dukedom had transferred from the House of Burgundy (1032–1361) to the House of Valois-Burgundy (1363–1482).

During the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War (1407–1435), the Burgundian State would clash with the Armagnac faction. During the Lancastrian War (1415–1453) phase of the Hundred Years' War, and after the assassination of John the Fearless (1419), they formed an alliance with the English between 1420 and 1435 with the Treaty of Troyes. In 1435, Charles VII of France concluded the Treaty of Arras with Philip the Good (the Duke of Burgundy 1419–1467), ending the civil war and gaining the support of the Burgundians against the English, which helped them win the Hundred Years' War.

After Philip the Good, the dukedom passed to:

- Charles the Bold, whose death ended the Burgundian Wars (1474–1477), a conflict between the Duke of Burgundy and the Old Swiss Confederacy and its allies.

- Mary of Burgundy. Mary had married the Maximilian I, the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, and the War of the Burgundian Succession (1477–1482) was a war over the partition of the Burgundian lands between Louis XI of France and the House of Habsburg.

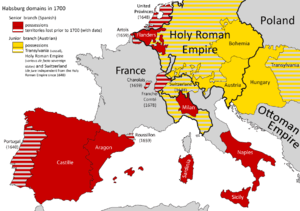

After the War of the Burgundian Succession and various treaties, territories including the Duchy of Burgundy would be lost to the French king. But the dukedom would continue with the Free County of Burgundy and the Burgundian Netherlands, passing to the Habsburgs and Habsburg Spain:

- Philip the Handsome, the first Duke of Burgundy of the House of Habsburg, who was also King Philip I of Castile.

- Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, who was also King Charles I of Spain (Castile and Aragon).

Charles V was succeeded by Philip II of Spain, Philip III of Spain, Philip IV of Spain, and Charles II of Spain, the last Habsburg ruler of Spain. After that the dukedom was claimed by the House of Bourbon, before returning to the House of Habsburg, and then to the House of Bourbon again.

Avignon Papacy

Avignon Papacy (1309–1376): was a period of during which the Popes resided in the Avignon, after manipulation by Philip IV of France. In all seven popes reigned during that period; they were all French, and heavily influenced by the French kings. During this period, the Antipope Nicholas V was crowned in Rome in 1328 at the behest of the Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV (Ludwig the Bavarian).

Western Schism

The Avignon Papacy would eventually lead to the Western Schism (1378–1417) within Roman Catholic Church. Two, even three, men simultaneously claimed to be the true pope, with loyalties divided between them; the non-Roman ones are considered as being antipopes (illegitimate popes). It happened after the death of Gregory XI in 1378, who had moved back to Rome in 1376. Difficulties with the newly-elected Pope Urban VI in Rome resulted in the establishment of rival Antipope Clement VII in Avignon, who was succeeded by Antipope Benedict XIII in 1394. There were also rival antipopes in Pisa during the period 1409 to 1415, after the controversial Council of Pisa.

The Western Schism ended with the Council of Constance (1414–1418), held just north of Switzerland. Pope Gregory XII and the Pisa-based Antipope John XXIII stepped down in 1415; and in 1417 Pope Martin V was elected. Avignon-based Antipope Benedict XIII refused to step down and was excommunicated.

Hundred Years' War

Hundred Years' War (1337–1453): was a series of wars in France, primarily between the French and the English. It was triggered by a series of disagreements between the French monarch Philip VI "the Fortunate" (who reigned 1328–1350), and the English House of Plantagenet monarch Edward III (who reigned 1327–1377). This ended in Philip VI confiscating the Duchy of Aquitaine (then essentially corresponding to Gascony) from the Duke of Aquitaine Edward III. Philip VI was the first king of the House of Valois, and succeeded Charles IV "the Fair"; this created a rival claim to the French throne of Edward III through his mother Isabella, the sister of Charles IV. The war can be divided into three phases:

Edwardian War (1337–1360)

The English were led by Edward III and his son Edward the Black Prince. With the Battle of Sluys (1340), the English gained command of the seas. The English had a great victory at the Battle of Crécy (1346); and after the Siege of Calais (1346–1347) Calais was held by the English until 1558. The French King Philip VI was succeeded by his son John II (1350), who was captured by the English at the Battle of Poitiers (1356).

With the Treaty of Brétigny (1360), Edward III renounced the French crown, but became Lord of Aquitaine (1360–1362), with Aquitaine as an independent and much enlarged territory than before the war. Conflict was extended between the English and French in the War of the Breton Succession (1341–1365), the Castilian Civil War (1351-1369), and the War of the Two Peters (1356–1375).

Caroline War (1369–1389)

When the French King John II died in captivity in 1364, his son, Dauphin Charles, succeeded him as Charles V "the Wise"; he again claimed Aquitaine in 1369 from Edward the Black Prince, the son of Edward III and Prince of Aquitaine (1362–1372). The French had a capable general in Bertrand du Guesclin. The war was mostly characterized by a Fabian strategy by the French, avoiding open conflict and concentrating on skirmishes, although there was a series of battles. English command of the seas ended at the Battle of La Rochelle (1372). Conflict during this period included Despenser's Crusade (1382–1383), and the warfare during the 1383–1385 Portuguese interregnum crisis.

The French King Charles VI "the Beloved" (the son of Charles V) and the English King Richard II (the son of Edward the Black Prince) would agree the Truce of Leulinghem in 1389, with English-held lands in France much reduced.

Lancastrian War (1415–1453)

The English House of Lancaster King Henry V succeeded Henry IV in 1413, and reasserted the claim to the French throne of Edward III; Henry V would have a great victory against the French at the Battle of Agincourt (1415). In 1419, Rouen and Normandy fell to Henry V, and Henry V formed an alliance with Burgundy. In 1420, Henry V and Charles VI signed the Treaty of Troyes, that Henry V would marry Catherine of Valois (daughter of Charles VI of France), and that their heir would inherit both kingdoms, and that the Dauphin (the son of Charles VI) was disinherited.

In 1422 Henry V of England and Charles VI of France both died, creating rival claimants to the French throne:

- Henry VI, the nine-month-old son of Henry V, who was crowned king of France in 1431.

- Charles VII "the Victorious", the 19-year-old Dauphin (prince) and son of Charles VI. Charles VII would eventually be victorious over Henry VI.

At the Siege of Orléans (1428–1429), which was held by the French, Joan of Arc rallied the French troops, and the seige was lifted nine day later. Soon after a series of French victories, including the decisive Battle of Patay (1429), and the crowning of the Charles VII at Reims Cathedral (1429), further boosted the French. However Charles the Victorious and Joan of Arc were unsuccessful at the Siege of Paris (September 1429), which was held by the English; and subsequently Joan of Arc was captured by the Burgundians (March 1430), and then executed by the English (May 1431).

The resolution of the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War (1407–1435) gave Charles VII the support of the Burgundians. The French had major victories at the Battle of Formigny (1450) and Battle of Castillon (1453), resulting in the loss of all English territories in France by 1453, with the exception of the Pale of Calais.

War of the Roses

.jpg)

After the reign of English King Richard II (1377–1399), the Plantagenets would divide into two cadet branches; the House of Lancaster and the House of York. The House of Lancaster would rule first, with the reigns of Henry IV; and then his son Henry V; and then his son Henry VI. Henry VI's early reign was overseen by a Regency government (1422–1437). When Henry VI finally became ruler, his ineffective rule and mental instability contributed to the the loss of the Hundred Years' War (1453); and in England, a collapse of law and order. Henry VI's wife Margaret of Anjou became the de facto ruler. Henry VI's cousin, Richard of York (the 3rd Duke of York), began to oppose him and his wife's clique.

Wars of the Roses (1455–1487): began when civil war broke out between supporters of the the House of Lancaster and the House of York:

- The House of Lancaster, symbolised by the Red Rose of Lancaster, supported the continuing reign of Henry VI.

- The House of York, symbolised by the White Rose of York, supported Richard of York; and after Richard's death in 1460, his son Edward, who would later reign as Edward IV.

After a series of Yorkist victories, Edward IV became king between 1461–1470. But in 1469, the Earl of Warwick threw his support behind Henry VI; a series of battles ended with Edward IV fleeing to Flanders in 1470, and the restoration of Henry VI's reign. But at the Battle of Tewkesbury (1471), Henry VI's forces were again defeated by Edward IV, who then returned to London unopposed to resume his reign; with Henry VI, and his son Edward, Prince of Wales, dead.

Edward IV would reign for a further 12 years, before dying in 1483. He was succeeded by his 12-year-old son Edward V, who reigned for 78 days, but was never crowned. Edward V and his brother Richard were kept in the Tower of London, and they were later called the Princes in the Tower. Their fate is uncertain, but they were probably murdered by their uncle, who then reigned as Richard III (1483–1485). Richard III would later be defeated and killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field (1485), by Henry Tudor, who would reign as Henry VII (1485–1509). This ended the Plantagenet dynasty, and began the Tudor dynasty. Henry VII was distantly related to John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, through his mother; and he married Elizabeth of York, the daughter of Edward IV; his emblem, the Tudor rose, combined the red and white roses of Lancaster and York. The War of the Roses ended in 1487 with defeat of the Yorkist rebel John de la Pole, 1st Earl of Lincoln.

Holy Roman Empire and Hanseatic League

Rulers of states of the Holy Roman Empire around 1300 included the Houses of Wittelsbach, Luxembourg and Habsburg.

- The House of Wittelsbach lands included Bavaria (including the Upper Palatinate), Palatinate, Hainaut, Seeland, Holland and Friesland.

- The House of Luxembourg lands included Luxembourg, Bohemia (including Moravia and Silesia), Brabant and Brandenburg.

- The House of Habsburg lands included Inner Austria (Duchy of Austria, Styria, Carinthia and Carniola), Tyrol and Further Austria (Sundgau and Breisgau).

Hanseatic League (from 1358) was a league of guilds and market towns of Germanic origins, mostly south of the North Sea and Baltic Sea. The Hansa were a trade league, who were also committed to the mutual defense of the members, forming a political-economic alliance. Note that "Hanseatic" is the adjective for the noun Hansa, but also the adjective for hanse (historical for a merchant guild).

They consisted of:

- Hansa Proper: Hanseatic cities in territories divided into quarters. The quarters were the Wendish (Wendish and Pomeranian); Saxon (Saxon, Thuringian and Brandenburg); Baltic (Prussian, Livonian and Swedish); and Westphalian (Rhine-Westphalian and Netherlands, including Flanders).

- Kontore: Hanseatic foreign commercial enclaves, forming the Kontor quarter. Kontore is plural of kontor, literally "branch office". Spread throughout Europe, they were not Hanseatic members, but closely related to Hansa.

- Other ports with Hanseatic trading posts, and cities with a Hanseatic communities.

They would dominate trade in Northern Europe for the next three centuries, before gradually falling apart by the late 17th century. They were an early example of a trade bloc, and these would gradually become to dominate world trade; an example being the European Economic Community of the 20th century, that would become the present-day European Union.

Rise of Muscovy

Kievan Rus' (882–1240): was an early progenitor to Russia. A loose federation of East Slavic and Finnic peoples, it was founded by the Rus' people, who are thought to be Varangians (Vikings). It was composed of a number of principalities and other territories; the city of Kiev was the nucleus of the state, and it was ruled by the Grand Prince of Kiev. Vladimir the Great was a Prince of Novgorod who became Grand Prince of Kiev 980–1015; he consolidated the realm, and converted to Christianity in 988. Roman the Great (Roman Mstislavich) was another Prince of Novgorod and Grand Prince of Kiev 1170–1205, and had victories against Cumania (also known as the Cuman-Kipchak Confederation), a large Turkic confederation south-east of the Rus'.