The early modern period was circa 1500–1750 AD, or ending at the French Revolution (1789), or at 1800.

See also: Wikipedia:Early modern period

States and territories of the early modern period

States and territories of the early modern period included:

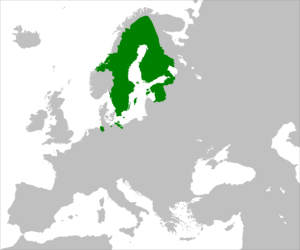

- Northern Europe

- The Kingdom of England (which included Wales from 1284) would later become the Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1800) by including the Kingdom of Scotland; the Kingdom of Ireland (1542–1801) was a client state of the British. The end of the Kalmar Union (1397–1523) led to two states: Denmark–Norway (1523–1533 & 1537–1814); and the Swedish Empire (1611–1721), which included Finland.

- Western and Central Europe

- Included France; and the Holy Roman Empire, with lands of Brandenburg-Prussia and the lands of the Austrian Monarchy. The Habsburg Netherlands (1482–1794) would become the Seventeen Provinces (1549–1581), covering the Low Countries. The Seventeen Provinces gave rise to the Dutch Republic, an independent state from 1581–1795; and the Southern Netherlands (until 1794). The Old Swiss Confederacy (c. 1300 – 1798) gained de facto independence from the Holy Roman Empire after the Swabian War (1499), where it fought against them and the Swabian League; it formally gained independence after the Thirty Years' War (1648).

- Eastern Europe

- The Grand Duchy of Lithuania created a bi-confederation with the Kingdom of Poland to create the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795). The Terra Mariana (of present day Estonia and Latvia between 1207–1561) collapsed into separate states. The Duchy of Prussia (1525–1701) was a Protestant secularization of the earlier Teutonic State. The Balkans were dominated by the Ottoman Empire, with vassals such as Wallachia and Moldavia; there were also the Habsburg lands of the Hungarian crown, Venetian possessions and the Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro (1516–1852). Further east was the Tsardom of Russia/Russian Empire (1547–1721 & 1721–1917).

- Iberian Penisinula

- The Spanish Empire included present day Spain (Castile and Aragon); but extended over Europe, including much of Italy and the Habsburg Netherlands. Possessions in Italy and the Netherlands were lost during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714). It would also include Portugal during the Iberian Union (1580-1640).

- Italian Peninsula

- Included the Papal States and Venice. Other northern Italian states were nominally within the Holy Roman Empire, but many Italian city-states had de facto independence: important ones (in the 16th century) included Genoa, Florence, and Savoy; the Duchy of Milan became part of the Spanish Empire, as well as the southern states of Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia. Lesser northern Italian states at that time included Siena, Modena, Ferrara, Lucca, Montferrat, Saluzzo, Asti, and Mantua.

Russia, Sweden, and Poland

Russian Tsardom and Empire

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_15939.tif.jpg)

Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721) became a new name for Muscovy, also known as the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Ivan the Terrible (Ivan IV Vasilyevich) the grandson of Ivan III, was declared "Tsar of All Rus'" (1547–1584), after ruling as Grand Prince of Moscow (1533–1547). Ivan the Terrible conquered the Khanate of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Sibirean khanates. Later on, the rest of Siberia would fall to the Russians, and by the mid-17th century Russia had expanded to the Pacific Ocean.

The Rurik dynasty were rulers of Kievan Rus' (after 882), as well as the successor principalities of Galicia-Volhynia (after 1199), Chernigov, Vladimir-Suzdal, and the Grand Duchy of Moscow; they also ruled the Tsardom of Russia. The Time of Troubles was between the death of Feodor I in 1598 and the accession of Michael I in 1613; during this time the Russian famine of 1601–1603 devastated Russia. Vasili IV was tsar between 1606 and 1610, but this was disputed, and there was numerous other usurpers and imposters. After the Time of Troubles, the House of Romanov ruled Russia, beginning with Michael I, and ending with Nicholas II, the last tsar of Russia who was deposed in 1917. By the 18th century, many Cossacks (an East-Slavic people) had been transformed into a special military estate of Russia.

Russian Empire (1721–1917): was declared by Peter the Great (Peter I), who reigned 1682–1725; as well as being emperor he retained the title of tsar. Peter the Great moved the capital to St. Petersburg in 1712, which remained there until 1917; he also won the Great Northern War in 1721. The Empress Catherine the Great (Catherine II), who reigned 1762–1796, presided over a golden age, with rapid expansion of the empire, and the Russian Enlightenment with advancement particularly in the arts. Alexander Suvorov was an outstanding general for the Russians, particularly during the Russo-Turkish Wars during the late 18th century; the Russo-Turkish Wars continued from the 16th to 20th centuries.

The Russian Empire continued until the 20th century, until the Russian monarchy was deposed, and the empire was succeeded by the Russian Republic (1917). It then became the Russian SFSR (Soviet Federative Socialist Republic) (1917–1991), which became a part of the Soviet Union or USSR (1922–1991).

Sweden and the Northern Wars

Before the Swedish Empire, Russia and Sweden had fought in two Northern Wars: the Russo-Swedish War of 1554–1557, and the Livonian War (1558–1583). After Russia was defeated, Terra Mariana (also called Old Livonia) was divided between the victors: Sweden, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and Denmark–Norway. With the Northern Seven Years' War (1562–1570), Sweden had clashed with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Denmark–Norway, without territorial changes.

Swedish Empire (1611–1721) was a great power in Europe and a rival to Russia in Eastern Europe. The Swedish Empire was founded by Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (or Gustav II Adolf, who reigned 1611–1632); he led Sweden to military supremacy during the Thirty Years' War, including great victories such as the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631), before dying at the Battle of Lützen (1632).

During the Second Northern War (1655–1660), Sweden and its allies fought against many opponents; these included the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Russia (Muscovy), Brandenburg-Prussia (at times an ally), the Austrian Monarchy, and Denmark–Norway. NB that the term "First Northern War" can refer to a number of conflicts, including the Second Northern War. Major aspects included:

- Russo-Swedish War of 1656–1658, without territorial changes.

- Dano-Swedish Wars of 1657–1658 and 1658–1660, with territorial changes between Denmark–Norway and Sweden.

- Russo-Polish War of 1654–1667, also called the Thirteen Years' War, coincided with the Second Northern War to some extent; it ended with significant Russian territorial gains from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

- The Swedish-Russian Deluge (Potop szwedzko-rosyjski) was the occupation of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during these wars, mainly by Sweden, Russia (Muscovy), Brandenburg-Prussia, and Khmelnytsky's Cossacks; it caused widespread destruction and looting, and a huge loss of life.

Sweden mostly gained territories as a result of this war. With the Scanian War (1674–1679), also called "Swedish-Brandenburgian War", Sweden ceded some Pomeranian areas to Brandenburg-Prussia.

Great Northern War (1700–1721) had a Russian coalition fighting against a Swedish coalition, for supremacy in Northern Europe. It began when Russia, Denmark–Norway, Saxony, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth sensed an opportunity and declared war on the Sweden, then ruled by the young Charles XII. The Caroleans (the soldiers of the Swedish kings Charles XI and Charles XII) had some great victories against Russia and other countries during this period, in many cases defeating far larger armies. But eventually there was victory by the Russian coalition; Russia, Prussia, Denmark-Norway, and other states would gain territories.

After the Great Northern War, both Sweden and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth would decline, while Russia and Prussia would continue to rise. In 1809 eastern Sweden would be lost to Russia, which became the highly autonomous Grand Principality of Finland. During the Napoleonic Wars, Sweden allied itself with France; and after the Battle of Leipzig (1813), and a military campaign, the Swedish King Charles XIII managed to force Denmark–Norway, an ally of France, to cede Norway, in exchange for northern German provinces; Sweden–Norway lasted from 1814 to 1905. The 1814 campaign was the last time Sweden was at war.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Kingdom of Poland created a bi-confederation with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to create the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795). During this period the King of Poland would also be the Grand Duke of Lithuania, although this personal union had existed since 1386. The "Golden Liberty" meant that the king was elected, and that the nobles held considerable power. The Poles were mostly West-Slavic, and the Lithuanians were mostly Balts.

During the Polish–Muscovite War (1605–1618), the Poles occupied Moscow between 1610 and 1612. During the Swedish-Russian Deluge (1648–1667), approximately one third of its population was lost, as well as its status as a great power, due to invasions by Sweden and Russia. The Polish King John III Sobieski allied with Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I; in 1683, at the Battle of Vienna, they defeated the Ottomans Empire, marking a turning point in the Ottoman–Habsburg Wars and Polish–Ottoman Wars.

After the Great Northern War, the Commonwealth would further decline, becoming a protectorate of the Russian Empire in 1768. The Partitions of Poland (1772–1795) was the partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth between Russia, Prussia, and the Austrian Monarchy; it was instigated by Catherine the Great of Russia, Frederick the Great of Prussia, and Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor. Poland would cease to be, until resurrected by Napoleon as the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807; after a tumultuous history it finally became the present-day Third Polish Republic, established 1989–1991. Lithuania would not become finally independent of Russia until 1990.

Decline of the Holy Roman Empire

.svg.png)

In 1500 and 1512, within the Holy Roman Empire, Imperial Circles where created. These included Bavarian, Franconian, Upper and Lower Saxon, Swabian, Upper Rhenish, Lower Rhenish–Westphalian, Austrian, Burgundian, and Electoral Rhenish Circles. Outside the Imperial Circles were the lands of the Bohemian Crown (included Silesia), the Old Swiss Confederacy (1291–1798), as well as the Italian territories.

Imperial Circles consisted of Imperial Estates, ruled by Imperial Princes. The Imperial Diet, the highest representative assembly, consisted of three colleges: an Electoral College of seven Prince-electors, who elected the emperor; a college of Imperial Princes; and a college of Free and Imperial Cities. Charles V was the last Holy Roman Emperor to be crowned by a pope, Pope Clement VII in 1530.

Since the 13th century the Holy Roman Emperor had began to lose power and territory. Gradually, the Holy Roman Emperor's power became largely nominal, with real power going to the rulers of the highly autonomous Imperial Estates; they held "immediacy", meaning that they were answerable only to the emperor. Two major power-bases within the Holy Roman Empire grew in influence:

- Brandenburg (as a Margraviate or Province, 1157–1945): which would provide the basis for Brandenburg-Prussia and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia would de facto lead the North German Confederation of 1867, which gained a new constitution as the German Empire in 1871, under the permanent presidency of Prussia.

- Austria (as a Duchy or Archduchy, 1156–1918): which would provide the basis of the Austrian Monarchy, which would later become the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary. After 1440, the Austrian monarch usually held the office of Holy Roman Emperor.

Both Brandenburg and Austria would gain territories both inside and outside of the Holy Roman Empire. The rest of the Holy Roman Empire power-base was split between miscellaneous states: larger ones in the early modern period included Bavaria (north was formerly Franconia), Saxony, Hanover, and Lorraine.

During the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), religious divisions in Holy Roman Empire would further weaken it as a unified entity. The Habsburg Austrian Monarchy, which dominated the office of Holy Roman Emperor, would lose territories, although there would be territorial gains for Brandenburg-Prussia. Austria would fight against Prussia in the Silesian wars (1740–1763), and Silesia was a theater in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). Voltaire quipped “... the Holy Roman Empire was in no way holy, nor Roman, nor an empire”, and the empire had become greatly fragmented between the semi-autonomous states by the late nineteenth century. The German mediatisation (1802–1814) reduced the number of German states from almost 300 to just 39.

The Holy Roman Empire would eventually be dissolved after the Austrian defeat by France under Napoleon in the War of the Third Coalition (1803–1806); and Prussia would be defeated by Napoleon in the War of the Fourth Coalition (1806–1807).

House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern was a German dynasty from Hechingen in Swabia, who took their name from Hohenzollern Castle in the Swabian Alps. Most importantly, the Brandenburg-Prussian branch would rule Brandenburg-Prussia, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the German Empire

The first branch was the Swabian branch who ruled Zollern, a county in the Holy Roman Empire which from 1218 was called Hohenzollern, and whose capital became Hechingen. At first they ruled as Counts of Zollern (1061–1204) and Hohenzollern (1204–1575). They would then rule Hohenzollern-Haigerloch, Hohenzollern-Hechingen, and Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen during the period of 1576 to 1849. After 1849 to the present day they continued as Heads of the Princely House of Hohenzollern.

Other than the Swabian branch, other ruling branches were:

- Brandenburg-Prussian branch, which included the Electors and Margraves of Brandenburg, 1415 to 1806. They also included the rulers of Prussia (1525–1918), and the German Emperors (1871–1918): these were the Dukes of Prussia (1525–1701), the Kings in Prussia (1701–1772), and the Kings of Prussia (1772–1918). They also included Margraves of Brandenburg-Küstrin, and Brandenburg-Schwedt.

- Franconian branch, which included some Burgraves of Nuremberg; Margraves of Brandenburg-Kulmbach, Brandenburg-Ansbach, and Brandenburg-Bayreuth; and Dukes of Jägerndorf.

- Kings of the Romanians (1866–1947), of the Kingdom of Romania (1881–1947).

Brandenburg-Prussia and Frederick the Great

Brandenburg-Prussia (1618–1701): was formed from territories that initially included, within the Holy Roman Empire, the Margraviate of Brandenburg, the Duchy of Cleves, and the counties of Ravensberg and Ravenstein. Outside of the Holy Roman Empire it initially included the Duchy of Prussia. It would later considerably expand its territories, both inside and outside the Holy Roman Empire. Prussia had developed from the State of the Teutonic Order, a state founded after the Teutonic Knights had conquered the lands of the Old Prussians (who were pagan Balts), after the Prussian Crusade of 1217–1274 (one of the Northern Crusades). It then became the Duchy of Prussia (1525–1701), a protestant state; it then entered personal union with Brandenburg in 1618, when John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, became Duke of Prussia.

Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918) succeeded Brandenburg-Prussia, and was established after Frederick III, Elector of Brandenburg, crowned himself "King in Prussia" as Frederick I on 18 January 1701. Early kings would be styled as "King in Prussia" rather than "King of Prussia"; this continued until 1772. It would gain much territory both inside and outside of the Holy Roman Empire and successors. It would eventually form the nucleus of the German Empire (1871–1918).

Frederick the Great (or Frederick II or "The Old Fritz") ruled the Kingdom of Prussia 1740–1786; he was the first Elector of Brandenburg to claim to be "King of Prussia" in 1772, rather than "King in Prussia". He had many military successes, particularly in the Silesian Wars (of 1740–1763) where he gained Silesia (a Bohemian territory) from the Austrian Monarchy. He also acquired Polish territories during its partition. Apart from his military successes, he was seen as a leading monarch of the Enlightenment.

Frederick fought in three Silesian wars against Austria:

- The First Silesian War (1740–1742) and the Second Silesian War (1744–1745) were theaters of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), in which Prussia fought against Austria and its allies. This led to the annexation of Silesia from the Habsburgs.

- The Third Silesian War (1756–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), where Prussia was part of the Great Britain coalition, and was opposed by Saxony (who he occupied), and Austria, France, Russia and Sweden. The Prussians maintained all their territories, and it was considered as the "Miracle of the House of Brandenburg".

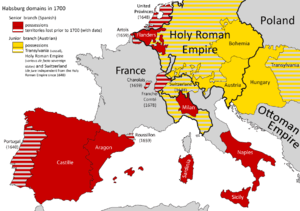

Houses of Habsburg and Habsburg-Lorraine

.svg.png)

The House of Habsburg (or House of Austria) was a one of the most important dynastic royal houses in the history of Europe. Named after Habsburg Castle (in present-day Switzerland), they were powerful monarchs of many dominions across Europe during the Middle Ages and modern period. It was succeeded by the House of Habsburg-Lorraine (a branch of the House of Lorraine) with the extinction of the male line but the continuation of the female line.

The key monarchies for the Houses of Habsburg and Habsburg-Lorraine were the following:

- Monarchs of Austria between 1282 and 1918, as dukes, archdukes or emperors, or female equivalents. The Austrian branch gained many dominions both inside and outside of the Holy Roman Empire.

- Monarchs of Spain (Castile and Aragon) between 1516 and 1700. The Spanish branch was mostly separate from the Austrian branch, and would have a significant presence in the New World, the Netherlands (then covering the Low Countries), and Italy and its surrounding islands.

- Holy Roman Emperors for most of the period 1440 to 1806. It was an elective monarchy, and usually held by the Austrian monarch.

Austrian Monarchy

Austrian Monarchy, or Habsburg Monarchy (1282–1804), is an unofficial umbrella term for lands held in personal union with the monarchs of Austria (of the House of Hapsburg and later Habsburg-Lorraine). After 1804 it would be known as the Austrian Empire (as the Archduke of Austria also became Emperor of Austria); and then from 1867 to 1918 as Austria-Hungary (after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867). Lands would be gained from both within and outside of the Holy Roman Empire. The Austrian Monarchy would include:

- Within the Holy Roman Empire: the Hereditary Lands, which included the Archduchy of Austria (1453–1806), Inner Austria, County of Tyrol, and Further Austria. It also included the Lands of the Bohemian Crown (1526–1918), which early on included Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, and Lusatia.

- Outside of the Holy Roman Empire: it included the Lands of the Hungarian Crown (1527–1918): Hungary, Croatia, Slavonia (after 1699), and the Principality of Transylvania (after 1711), as well as some military frontiers. N.B. that Croatia today is Croatia proper, Slavonia, Istria and Dalmatia. They also gained the Spanish Netherlands, Naples, Milan and Sardinia after the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714). Later on, during the Partitions of Poland (1772–1795), they gained some of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Holy Roman Emperors during the modern period

The House of Habsburg were Holy Roman Emperors between 1440 and 1740, beginning with Frederick III, the Peaceful. During this period the Holy Roman Emperor was also the Archduke of Austria, although Charles V was only archduke for two years. This ended in 1740 after the reign of the emperor Charles VI. The next two Holy Roman Emperors were:

- Charles VII (emperor 1742–1745) was also Elector of Bavaria, and House of Wittelsbach, and the first non-Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor for three centuries.

- Francis I and Maria Theresa (emperor and empress 1745–1765). Francis I was of the House of Lorraine; he was also Archduke of Austria through his marriage to Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria and daughter of the Habsburg emperor Charles VI.

The uncertainty over the Austrian succession through the female-lineage of Maria Theresa led to the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). The last three Holy Roman Emperors were House of Habsburg-Lorraine and archdukes of Austria:

- Joseph II (emperor 1765–1790) was the son of Francis I, and the brother of Marie Antoinette (who would marry the King of France Louis XVI). He was a leading proponent of enlightened absolutism, and a supporter of the arts, such as the composers Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri.

- Leopold II (emperor 1790–1792) briefly succeeded his brother Joseph II.

- Francis II (emperor 1792–1806) was the son of Leopold II, and the last Holy Roman Emperor. He proclaimed himself Emperor of Austria in 1804, and later archdukes of Austria would also be emperors of Austria.

After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, as both emperors and archdukes of Austria, would rule the the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary. This ended in 1918 when Austria-Hungary declared itself to be the Republic of German-Austria, which became the First Austrian Republic in 1919, a much reduced state in terms of territory.

Ottoman–Habsburg wars and Suleiman the Magnificent

Ottoman–Habsburg wars (1526–1791) began with the Ottoman victory at the Battle of Mohács (1526); Suleiman the Magnificent, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, defeated Louis II of Hungary, King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia, who died soon after. This ended the Ottoman–Hungarian wars, and would eventually result in the partition of Hungary between:

- Royal Hungary (1526–1867), the Kingdom of Hungary of the Habsburg Monarchy, first ruled by Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor

- Eastern Hungarian Kingdom (1526–1551 and 1556–1570), which would become the semi-independent Principality of Transylvania (1570–1711)

- Ottoman Hungary (1541–1699), of the Ottoman Empire, after the seizure of Buda by the Ottomans in 1541

It also marked the beginnings of the Ottoman–Habsburg wars, a 250-year struggle between the Habsburgs and the Ottoman Empire for European territories. It also marked the end of Hungary as an independent territory until the 20th century.

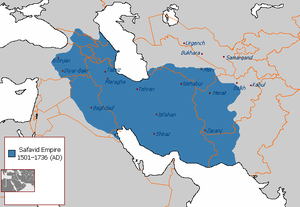

Suleiman the Magnificent was the Ottoman Sultan 1520 to 1566. He conquered the Christian strongholds of Belgrade (1521) and Rhodes (1522); but after the Battle of Mohács, he was curtailed by the Austrians at the unsuccessful Siege of Vienna of 1529. He finally captured and occupied Buda (the Hungarian capital) following a siege in 1541. He also fought with the French against the Habsburgs in the Italian Wars. With the successful Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555) he gained territories from the Iranian Safavid dynasty; he also expanded the North African territories. His reign ended the Classical Age of the Ottoman Empire (1453–1566), characterized by a large expansion of territories.

Great Turkish War (1683–1699): was a campaign in the Ottoman–Habsburg wars that followed a period of peace after the Long Turkish War (1593–1606). At the Battle of Vienna (1683), the Ottomans were defeated after a two month siege of the city. John III Sobieski, the King of the Poland, helped the Austrians in the battle, along with a Holy Roman Empire army; the Winged Hussars, an elite Polish cavalry, delivered a final deadly blow. The Holy League of 1684–1699 that formed afterwards eventually ended the Great Turkish War; with the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) most of Hungary, and Slavonia, were gained by the Habsburgs. Transylvania fell to the Habsburgs in 1711.

The Great Turkish War was followed by the Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718), Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739), and Austro-Turkish War (1788–91). The Ottoman–Habsburg wars ended Ottomans expansion into Europe.

Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain (1516–1700) began with Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor 1519–1556. His other titles included:

- King of Spain (Castile and Aragon, 1516–1556) as Carlos I (Charles I of Spain)

- Archduke of Austria, but only between 1519 and 1521

- Duke of Burgundy (1506–1555), and therefore Lord of the Netherlands

- By being Holy Roman Emperor he also had the titles King of Germany, and King of Italy (the last Holy Roman Emperor to claim the title)

The Crown of Aragon consisted of Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Naples, Sicily and Sardinia. Aragon had previously controlled Milan, and this was recaptured by Charles V, and later recognised by the French in 1559. The Crown of Castile would encompass a huge colonial empire. After the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) Castile and Aragon would be unified. Burgundy included what would become the Seventeen Provinces (covering the present-day Low Countries), and the Free County of Burgundy (also known as Franche-Comté).

Charles V inherited the Spanish House of Trastámara bloodline through his mother Joanna of Castile (who was nominally a co-monarch, but was imprisoned after being pronounced insane); who had married his father Philip I of Castile (by right of his wife King of Castile for a short time before dying). But he actually succeeded his mother's parents, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon; Ferdinand II ruled Aragon as king, and Castile as Governor and Administrator after the death of Isabella. As king of both Castile and Aragon, he was the first monarch of both crowns (if you ignore his mother), with his grandparents being the first co-monarchs. Charles V was heir to Austria through his father's father Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor; but after two years this passed to his brother Ferdinand I. He was Duke of Burgundy through his father Philip I of Castile, who had inherited his dukedom from his mother Mary of Burgundy.

Charles V was involved in three major conflicts: the Italian Wars (with France), the Ottoman–Habsburg wars, and the Protestant Reformation (which he opposed). He also quelled some rebellions. Charles V brought about the divergence of two ruling branches of the Habsburgs:

- The junior branch of the Austrian Monarchy, with Charles being succeeded by his brother Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I (1556–1564), who was also Archduke of Austria after 1521, and king of Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia.

- The senior branch of Habsburg Spain (1516–1700), with Charles being succeeded by his son Philip II of Spain.

Philip II of Spain: was King of Spain (1556–98), Duke of Burgundy, King of Portugal (1581–1598), and King of England and Ireland (during his marriage to Queen Mary). In Europe, Philip's empire included the Spanish Netherlands, and the Italian states of Naples, Sicily, Milan and Sardinia. He also had hegemony over all of Italy, with only Savoy and Venice having true independence. His colonial empire included, most importantly, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which included the Spanish East Indies, Spanish West Indies, and a substantial portion of North and Central America; South America included the Viceroyalties of New Granada, Peru and Rio de la Plata. In 1714, long after his reign, the Spanish Netherlands, Naples, Milan and Sardinia were ceded to Austria, and Sicily was ceded to Savoy.

Philip II presided over the start of the Spanish Golden Age (1556–1659), a period of flourishing in arts and literature in Spain. Philip financed the Holy League, who would have a great naval victory against the Ottomans at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. During his reign the Iberian Union (1580-1640) temporarily united Portugal and Spain, which would last until the Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1668). He sent the Spanish Armada to invade Protestant England in 1588, which ended in failure; several state bankruptcies also occurred during his reign.

Philip II was succeeded by Philip III of Spain, Philip IV of Spain, and Charles II of Spain, the last Habsburg ruler of Spain.

Italian Wars and Eighty Years' War

Italian Wars (also called the Habsburg–Valois Wars, 1494–1559): were principally the Habsburgs against the French Valois kings for Italian possessions, principally the Duchy of Milan and the Kingdom of Naples. It stemmed from the claim to the Kingdom of Naples of Charles VIII of France, with the death of Ferdinand I of Naples.

The leaders for the Habsburgs were the Holy Roman Emperors Maximilian, Charles V and Ferdinand I; and King Philip II of Spain; their supporters included Henry VIII of England and Mary I of England. The French Valois kings opposing them were Charles VIII, Louis XII, Francis I, and Henry II; their supporters included Suleiman the Magnificent. Various Italian states supported the factions. The wars began with Charles VIII's Italian War (1494–1498), Louis XII's Italian War (1499–1504), the War of the League of Cambrai (1508–1516), the War of Urbino (1517), and the Four Years' War (1521–1526). During the War of the League of Cognac (1526–1530), the Sack of Rome (1527) was by mutinous troops of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. It was followed the Italian War of 1536–1538, the Italian War of 1542–1546, and the Last Italian War (1551–1559).

The Italian Wars were largely unsuccessful for the French. The Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559) ended the Italian Wars, and was between France, Spain, England, and the Holy Roman Empire. In the treaty the French recognized Philip II as heir to Milan, Naples, Sicily and Sardinia, among other agreements.

Eighty Years' War, or the Dutch War of Independence (1568–1648): resulted in the Dutch Republic gaining independence from Spain. The Southern Netherlands (of roughly modern day Belgium and Luxembourg) remained under Spanish rule; it later became the Austrian Netherlands (1714–1794) until annexed by the French.

House of Bourbon and France

The House of Bourbon was a branch of the Capetian dynasty; it succeeded the House of Capet (987–1328) and Valois kings (1328–1589) as French monarchs. Branches would also become Spanish monarchs (see below), and Grand Dukes of Luxembourg (1964–present), as well as holding many other titles.

Henry IV, the Great (1589–1610) was the first Bourbon monarch, who ascended during the turmoil surrounding the French Wars of Religion. He was succeeded by Louis XIII, Louis XIV, Louis XV, and Louis XVI. Louis XVI was deposed in 1792 by the Great French Revolution (1789–1799). The Bourbons were later restored 1815–1830, with Louis XVIII and Charles X; and Louis-Philippe I (of the House of Orléans cadet branch) ruled 1830–1848. Cardinal Richelieu, King Louis XIII's chief minister between 1624–1642, helped transform France into a modern state.

Louis XIV (the Great or the Sun King) ruled France between 1643–1715. An absolute monarch, he greatly expanded the Palace of Versailles, and revoked the Edict of Nantes (leading to persecution of Protestants). Louis fought the Habsburgs and Dutch in the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678), which resulted in some territorial gains for France. Louis also fought the Grand Alliance (of the Habsburgs, English and Dutch) in the Nine Years' War (1688–97), which resulted in some territorial changes. He also fought in the War of the Spanish Succession (see below).

Second Hundred Years' War: the French had a great rivalry with the British during this period, mirroring that of the Habsburgs. As well as the Nine Years' War and War of the Spanish Succession, they also fought the British in the War of the Austrian Succession (1742–1748), Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), 2nd Carnatic War (1749–1754), Seven Years' War (1756–1763) and Anglo-French War (1778–1783). These wars, along with later wars after the fall of the Bourbons, the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802) and Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), are sometimes considered to be the Second Hundred Years' War. With the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette married, and Austria went from an ally of Britain to an ally of France, while Prussia became an ally of Britain.

Bourbon Spain

Bourbon Spain: from 1700, members of the House of Bourbon dynasty ruled Spain, beginning with Philip of Anjou, who would rule as Philip V of Spain; the Spanish Empire included territories in the New World and Europe. The Bourbons would be Spanish monarchs for much of its subsequent history, continuing to the present-day.

War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) had France (under Louis XIV) and their allies fighting the Grand Alliance, which included Austria, England and the Dutch Republic. The war was precipitated by the Habsburg ruler Carlos II of Spain (or Charles II) dying childless, and naming his successor as Philip of Anjou (later Philip V), the Bourbon grandson of Louis XIV and Carlos's half-sister Maria Theresa of Spain. The caused consternation for the Habsburgs, and the risk of a France–Spain superstate if both monarchies fell to a single ruler; therefore the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI claimed the throne. The Battle of Blenheim (1704) was a notable victory for the Grand Alliance. The war confirmed the Bourbon rule of Spain over the previous Habsburg monarchs; but Philip V had to renounce his place in the French succession; he also lost the Spanish Netherlands, Naples, Milan and Sardinia to Austria, and Sicily to Savoy.

The Spanish Bourbons were allies with the French Bourbons for some of their wars against the British: the War of the Spanish Succession, the War of the Austrian Succession, the Seven Years' War, and the Anglo-French War. But during the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718-1720) France fought against Spain (and Great Britain, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Dutch Republic).

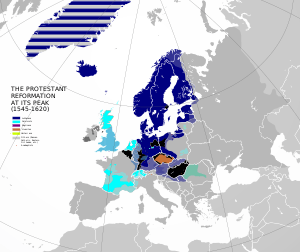

Reformation and religious turmoil

Protestant Reformation and earlier movements

_-_Portr%C3%A4t_des_Martin_Luther_(Deutsches_Historisches_Museum).jpg)

The Protestant Reformation was the establishment of Protestantism by in a 16th-century western Europe, whose religion was dominated by the Roman Catholic Church. The Protestant Reformation began in 1517, at Wittenberg, Saxony, when Martin Luther sent his Ninety-Five Theses to the Archbishop of Mainz; these protested against the sale of plenary indulgences by the clergy.

This was not the first time that the Catholic religion had been challenged. For example, in the High Middle Ages the Cathars of southern France had broken with Catholic doctrine; this led to the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229) and genocide of the Cathars.

Proto-Protestantism were similar movements that influenced the Protestant Reformation, and included:

- Hussites, a Christian movement of the pre-Protestant Bohemian Reformation who followed Jan Hus. They had established the Hussite religion in Bohemia after the Hussite Wars (1419–1434); this lasted for two centuries until their suppression after the Bohemian Revolt (1618–1620) of the Thirty Years' War.

- Waldensians. Founded in the 1170s by Peter Waldo, they would come to influence Anabaptism in particular.

- Lollards. Founded by John Wycliffe, a 14th century English theologian, they played a part in the English Reformation.

Early Protestant movements included:

- Calvinism, or the Reformed tradition, was based on the teachings of Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin and others; they included Presbyterians, Puritans, and Huguenots. Calvinism spread to the Dutch Republic, Scotland and southern France, and to a lesser extent in Germany, Hungary and England.

- Lutheranism was based on the teachings of Martin Luther, and Lutheran chutches became dominant in the north of Germany, and especially in the Scandinavian countries.

- Anglicanism was created by Henry VIII, and became the dominant religion of England as the Church of England; it incorporated aspects from the Reformed and Lutheran churches.

- Anabaptism was an early offshoot of Protestantism, and Anabaptist churches include the Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites fellowships.

- Unitarianism is an nontrinitarian theological movement, and Unitarian churches began in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Transylvania.

The Peace of Augsburg (1555) of Charles V allowed rulers within the Holy Roman Empire to choose either Lutheranism or Roman Catholicism as the official confession. Calvinism was not allowed in the Holy Roman Empire until the Peace of Westphalia (1648).

English Reformation and religious tensions

English Reformation: took place during the 16th century, when Henry VIII established the Anglican faith, followed by the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The Gunpowder Plot (1605) was an attempted assassination of the Protestant King James I of England by Catholics. The English Civil Wars (1642–1646, 1648–1649, 1649–1651) were partly religious in origin, and were part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (of England, Ireland and Scotland) between 1639–1651.

Anti-Catholic hysteria resulted in the Popish Plot (1678–81), a fictitious Catholic conspiracy to dethrone Charles II. The Glorious Revolution (1688) resulted in the ousting of the Catholic King James II by Parliament, who was replaced by the Protestant King William III and Queen Mary II. The Jacobite risings, especially prominent in 1715 and 1745, were failed Catholic uprisings that sought to reinstate James II and his descendants, including James Francis Edward Stuart ("The Old Pretender"), and Charles Edward Stuart ("the Young Pretender" or "Bonnie Prince Charlie").

Counter-Reformation

Counter-Reformation: was a period of Catholic resurgence in response to the Reformation. It began with the 25 sessions of the Council of Trent (1545–1563), which led to reform of Church doctrines and teachings, the foundation of seminaries for the training of priests, and new religious orders such as the Jesuits. The Inquisition was used to enforce the Counter-Reformation and suppress heresy; it included the Spanish Inquisition, the Roman Inquisition, and Portuguese Inquisition.

European wars of religion

European wars of religion of the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries, were largely a result of the religious differences stemming from reform.

The French Wars of Religion (1562–1598) were especially notable, with Roman Catholics against the Huguenots (French Protestants) following the death of Henry II of France; three millions deaths can be attributed to them. The Bartholomew's Day massacre (1572) was the massacre of between 30,000 and 100,000 Huguenots across France. Henry IV, a former Huguenot, issued the Edict of Nantes (1598) assuring conditional religious freedom. Later on, Huguenot rebellions (1621–1629) erupted after intolerance by Louis XIII. Louis XIV's Edict of Fontainebleau (1685) revoked the Edict of Nantes, and resulted in further persecution.

Other major European wars of religion include: the Thirty Years' War (see below); the War of the Three Kingdoms (1639–1651) of England, Scotland, and Ireland; the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) resulting in independence of the Dutch Republic from Spain; and the German Peasants' War (1524–1525) of the Holy Roman Empire. There was also a rise in witch trials between 1580 and 1630; over 50,000 people, mostly women, lost their lives, and religious tensions may have been a factor.

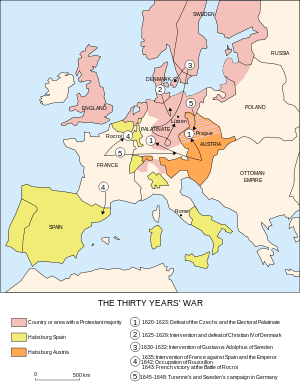

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) was an especially devastating European war of religion. It was fought roughly between two factions (although some allegiances would change during it). These included:

- The Catholic Habsburg states and allies, which included the Habsburg Austrian Monarchy and Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire Catholic League (mainly southern states which included Austria). The Holy Roman Emperors Ferdinand II and Ferdinand III, who reigned 1619–1637 and 1637–1657, spearheaded the Catholics.

- The anti-Habsburg states were mainly Protestant, with the notable exception of Catholic France. It also included the Scandinavian states of Denmark–Norway and Sweden; the Dutch Republic; and England and Scotland. Some Holy Roman Empire states were included, like Bohemia, Electoral Palatinate, Saxony, and Brandenburg-Prussia; but Saxony and Brandenburg-Prussia would join the Habsburgs in the fight against France. France was ruled by Louis XIII (1610–1643) and Louis XIV (1643–1715), and Cardinal Richelieu was First Minister of State 1624–1642.

There were many aspects to the war, but important ones include:

- Bohemian Revolt (1618–1620); was a revolt of the Hussites; see earlier movements above. It ended in success for the Habsburgs with the decisive Battle of White Mountain (1620).

- Danish phase (1625 to 1629). Christian IV of Denmark, king of Denmark–Norway, invaded the Holy Roman Empire to support the Protestants, but was soon forced to retreat. With the Treaty of Lübeck (1929), Denmark–Norway participation ended, and their nation would then decline.

- Swedish phase (from 1630). Protestant Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden invaded the Holy Roman Empire with considerable success, with battles such as the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631); this helped to establish Sweden as a great power. But Adolphus was killed at the Battle of Lützen (1632). The Peace of Prague (1635) more or less ended Holy Roman Empire civil war aspects.

- French phase (from 1635). Bourbon France, allied with Sweden, fought against the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs, despite France being Catholic. The French had a great general in the Viscount of Turenne. It included the Battle of Rocroi (1643), a decisive French victory over the Spanish.

- War in the Iberian Peninsula began in 1640 and continued after 1648. The Reapers' War (1640–1659), or the Catalan Revolt, was a part of the Franco-Spanish War of 1635 to 1659; it included the French occupation of Roussillon in the Eastern Pyrenees (1642). The Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1668) resulted in the breaking up of the Iberian Union of Spain and Portugal.

Other aspects include: the Palatinate campaign, the Habsburg conquest of the Electoral Palatinate (1620–1623); Ottoman support for Protestant Transylvania and the Polish–Ottoman War of 1620–21; Protestant Huguenot rebellions in France (1621–1629); the Peasants' War in Upper Austria, whose goal was to free Upper Austria from Bavarian rule (1626); and the War of the Mantuan Succession in northern Italy (1628–31). There were a total of eight million fatalities, including soldiers and civilians. There was widespread famine and devastation of the Low Countries as a result of the war.

Peace of Westphalia (1648) ended the The Thirty Years' War, although warfare continued in Iberia. The war weakened the Holy Roman Emperor and the Habsburgs, with power returned to the Imperial Estates. There was formal independence for the Dutch Republic with the end of the Eighty Years' War (the Dutch War of Independence, 1568–1648); and also for Switzerland. Territorial changes included gains by France, Sweden, and Brandenburg-Prussia. Princes within the Holy Roman Empire could determine their state's religion from Catholicism and Lutheranism, and now Calvinism was also acceptable.

The Franco-Spanish War concluded with the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), and France gained some territories there from Spain. With the Treaty of Lisbon (1668), Spain lost Portugal, but still held the Spanish Netherlands, and a greater part of Italy. Conflict between France and Habsburg Spain would continue with later wars, the War of Devolution (1667–68), the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678), the War of the Reunions (1683–1684), and the Nine Years' War (1688–1697).

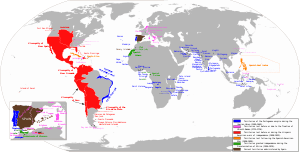

Age of Discovery and colonial empires

Age of Discovery: from circa 1400 to 1800. Lands include the Americas (the New World); southern Africa; Congo River; West Indies; India; Maluku Islands (Spice Islands); Australasia; New Zealand; Antarctica; Hawaii. Largely coincided with the Age of Sail (1571–1862).

Spanish Empire (1492–1975): Christopher Columbus landed in the New World in 1492. This was followed by La Conquista, the Spanish colonization of the Americas by the conquistadores. Cortes conquered the Aztecs after the Spanish–Aztec War (1519–21). In 1532 Pizarro conquered the Inca empire in Peru. The Maya and many other peoples were also conquered. Spanish lands in the Americas would be mainly divided into Viceroyalties: New Granada, New Spain, Peru, and Río de la Plata; and also Spanish Louisiana, and many other islands and territories.

Portuguese Empire (1415–1999): Vasco da Gama, during his voyage to India (1497–1499), performed the first navigation around South Africa, to connect the Atlantic and the Indian oceans. This would lead to Portuguese dominance in trade routes around Africa, particularly in the spice trade for around a century. Ferdinand Magellan and Juan Sebastián Elcano achieved the first global circumnavigation, 1519–1522. Portuguese influence in the East Indies and South Africa was curtailed by the Dutch–Portuguese War (1601–1663). In South America they ruled the Viceroyalty of Brazil.

The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) split the world between regions of Spanish and Portuguese influence, but this was ignored by other nations. This resulted in the Spanish being particularly active in Americas, while Portuguese influence in the Americas was limited to Brazil. The Portuguese established a large number of trading posts around the coasts of India, the East Indies, Africa and Arabia.

Major colonial empires that followed included the English (from 1583, which in 1707 became British); Dutch (from 1581); and French (1534–1980). In North America, the British, French and Spanish dominated. South and Central America was mainly Spanish, with the Portuguese in Brazil. Dutch colonies were split between the Dutch East India Company (particularly in the East Indies and South Africa) and Dutch West India Company (mainly on the east coast of the Americas). The Dutch discovered Australia in 1606, and New Zealand in 1642; both of these would later colonised by the British. Anglo-Dutch Wars: were a series of four wars fought in the 17th and 18th centuries; largely a result of English and Dutch rivalry, mainly over trade and overseas colonies; most battles were fought at sea.

The Danish empire (1536–1953) included Norway, Iceland and Greenland. The Swedish empire (1638–1663 and 1784–1878) mainly consisted of Finland and the Baltic states.

Atlantic slave trade was a major source of wealth to Europe and its colonies; beginning with the Portuguese in 1526, it reached a zenith between 1780 and 1800. In many cases it was a triangular trade; manufactured goods from Europe would be exchanged on the western coats of Africa for slaves; these slaves would be exported to North and South America, and the West Indies; and raw goods would be exported back to Europe. By volume, the empires trading slaves were the Portuguese, British, French, Spanish, and Dutch Empires. It is estimated that over 12 million Africans were shipped across the Atlantic, until it started being outlawed, firstly by Denmark in 1803, and then Britain in 1807. In 1888 Brazil became the last Western country to abolish slavery.

Golden Age of Piracy: spans the 1650s to the late 1720s. Main seas of piracy were the Caribbean Sea, the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea. It includes colorful pirates of the Caribbean such as Henry Morgan, William 'Captain' Kidd, 'Calico' Jack Rackham, Bartholomew Roberts and Blackbeard (Edward Teach).

Later on, in the late modern period (19th and early 20th centuries), Italy, Germany, Belgium, Japan and the USA established empires. The British Empire rapidly expanded in this period, and eventually included India, Australia and much of Africa. France colonized much of North Africa, and French Indochina (today Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia).

Rise of philosophy, the arts, science and trade

The Renaissance

The Renaissance began in Italy 14th century, and continued into the 17th century. It literally meant "rebirth", as it was seen as a rebirth of Classical learning and culture. There were developments in philosophy (particularly humanism), science, technology, and warfare. There were also artistic developments, including architecture, dance, fine arts, literature and music. There was renewed interest in Classical Roman and Greek texts, but also translations of Arabic texts. Early writers included Dante Alighieri, who wrote the Divine Comedy c. 1308 to 1320. Petrarch (1304–1374) was a particular proponent of humanism.

The High Renaissance, with Leonardo da Vinci, early Michelangelo, Raphael, and the architect Bramante, was between circa 1495 to 1520; it ended with the death of Raphael. Other artists included the sculptor Donatello, Titian, Sandro Botticelli, Masaccio, Giotto, Paolo Veronese, Tintoretto, Giovanni Bellini, Filippo Lippi, Paolo Uccello, and Antonio da Correggio. Filippo Brunelleschi was one of the foremost architects and engineers.

The House of Medici ruled Florence (as the Republic then Duchy of Florence, and as the Grand Duchy of Tuscany), for most of the period from 1434 to the early 18th century. They patronized many intellectuals associated with the Renaissance; these included Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Niccolò Machiavelli, Galileo Galilei and Sandro Botticelli. Lorenzo de’ Medici is particularly associated with this patronage.

The Roman Inquisition began in 1542, and suppressed some aspects of the Renaissance. It made some books forbidden, such as On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Sphere by Polish scientist Nicolaus Copernicus; first printed in 1543, it promoted the heliocentric theory of the Solar System. It also held trials against intellectuals; Galileo Galilei, who supported the work of Copernicus in his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), was put on trial.

Outside of Italy, Renaissance ideas soon spread across Europe to countries such as England, France, Germany, Hungary, the Low Countries, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Croatia, and Scotland. The invention of the printing press, which was greatly improved by the German Johannes Gutenberg circa 1439, helped in the dissemination of learning. In the English Renaissance, the works of William Shakespeare (1564–1616) are often regarded as the greatest in English literature. Other notable artists included: the German artists Hans Holbein the Younger, Hans Holbein the Elder, and Albrecht Dürer; the Dutch artists Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, and Jan van Eyck; and the Greek artist El Greco.

Baroque Period and Age of Enlightenment

Baroque Period (17th and 18th centuries) was characterised by highly ornate styles in architecture, music, painting, and sculpture. Artists included Velázquez, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Rubens, Poussin, and Vermeer. Baroque composers included Johann Sebastian Bach, Antonio Vivaldi, George Frideric Handel, Claudio Monteverdi, and Henry Purcell. It was followed by the Classical period of music; roughly between 1730 and 1820, it included Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Franz Schubert. Rococo, or "Late Baroque", spread across Europe in the mid-18th century.

Age of Enlightenment or Age of Reason was during the 18th century, and sometimes extended to the 17th century. Ideas that were developed were characterised by being secular, pluralistic, rule-of-law-based, with an emphasis on individual rights and freedoms. There was also an emphasis on science. Prominent scientists included Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, who built on the earlier work of Francis Bacon, the father of empiricism. Prominent philosophers included:

- French philosophers René Descartes (who contributed to rationalism), Voltaire (a particular advocate of freedom of speech and religion), Denis Diderot (and his Encyclopédie), and Montesquieu (and his theory of separation of powers).

- English philosophers John Locke and Thomas Hobbes, who both contributed to empiricism and social contract theory.

- Prussian-German philosopher Immanuel Kant, and the doctrine of transcendental idealism.

- Dutch-Portuguese philosopher Baruch Spinoza, a rationalist.

Voltaire and Benjamin Franklin greatly influenced the French Revolution and the American Revolution. The encyclopedia Encyclopédie (1751–72), edited by Denis Diderot, was a great success of the period.

Enlightened absolutism, the use of the the Enlightenment to espouse absolute monarchy, was a curious side effect; much later it was followed by the concept of the benevolent dictatorship. Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor 1765–1790, was a prominent monarch of the Enlightenment and enlightened absolutism, along with Catherine the Great of Russia, and Frederick the Great of Prussia.

Capitalism and mercantilism

Rise of capitalism: capitalism became a dominant force in the sixteenth century, with the abolition of feudalism. It took its name from capital, defined by Adam Smith as "that part of man's stock which he expects to afford him revenue". The investment of capital became the primary factor in the accumulation of wealth.

Mercantilism, the exporting goods from countries, also rose in importance, particularly as a result of colonialism, with the trade of slaves and goods across the Atlantic Ocean being particularly important.