Chapter 6

The Komiti

There is little or no reference that relates to the Macedonian hussars during the late 17th century; however the Macedonians called them "Komiti". The Komiti were Macedonian revolutionaries on horseback, and were part of a number of cheta. On December 24, 1751 an edict was issued by the Russian Senate, permitting the settling of Bulgarians, Macedonians, Serbians and Vlachs within the Russian Empire. Immigration to the Russian Empire was very common during the second half of the 18th century (1750-1800), and most of these immigrants were from the Ottoman Empire. Later the Russian royal edict of January 11, 1752 granted the formation of brigades from the Orthodox Serbian, Macedonian, Bulgarian and Vlach peoples. These brigades primarily were responsible in assisting the Russian Empire during certain battles against the Ottoman Empire.

On May 10, 1759, the Macedonian polevoy hussar regiment was founded, composed primarily of Macedonians, preceded by similar Serbian, Greek and Bulgarian regiments. The regiment had its own flag and its own coat of arms. There is also a mention of the Macedonian hussars in one of Aleksandar Matkovski's books, who is a Macedonian historian from the city of Krushevo, who has also written a book on Macedonian heraldry. He states that the formation of the Macedonian hussar regiment in Ukraine clearly set the Macedonians apart as a distinct Slavic ethnicity.[1] With the commencement of the Russo-Turkish War (1768-1774), the Russian Empire needed all the help they can get. It is unclear whether the Macedonian hussars assisted the Russian Empire in the battles located at Podolia, Ukraine. However the Macedonian Hussar Regiment assisted the Russian Empire during the Seven Years War. In 1773 the Macedonian Hussar Regiment was terminated.

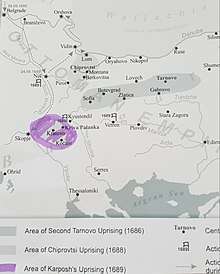

This was not the only war that involved the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire. Though a series of victories accrued by the Russian Empire led to substantial territorial conquests within the regions of Moldova, Yedisan and the Crimea. Looking back during 1750-1770's the situation among the Macedonian communities was a period that involved migration to other empires located within Europe. The reason for immigration was due to a number of factors : unemployment, forced changes in religion, the feeling of living a life without freedom, oppression, torture, and other factors such as discrimination and capitalism. In reference to capitalism this is referring to a form of agrarian capitalism, associated with landlords and peasants. Not just in the 17th century (1601-1700) but also into the following centuries, the crime rates increased due to high levels of unemployment. Unemployment was not also a growing factor, there was also the rise of homelessness which was mostly related to the effects of the agrarian capitalism. Some Slavic Macedonians, did well, acquired certain wealth, and began the gradual formation of a native middle class in places where Turks, Greeks, Jews, Vlachs and in some cases, Armenians had previously dominated crafts, trades and especially commerce and internal and foreign trade. Slavic Macedonians owned trading houses in Salonika, Kastoria (Kostur), Bansko, Seres, Edessa (Voden), and Ohrid with representation in Budapest, Vienna, Bucharest, Venice, Odessa, and Moscow. They would assist in the cultural and national awakening of Macedonian Slavs in the following century.[2] Anyway coming back to the late 17th century, foreign historians very rarely see or consider the Karposh uprising as a form of Macedonian nationalism. More appropriately historians from other countries also do not consider some revolutionaries to be of Macedonian origin, however Karposh is of Macedonian origin, as he was born in the region of North Macedonia. He's date of birth however is still unknown, what is also interesting is that he also shaped the history accounts for the overall battle up at Kumanovo. Regardless of whether or not foreign historians consider the Karposh uprising, as a form of Macedonian nationalism the Macedonian historians and archaeologists most definitely view or see the uprising as a form of nationalism or Macedonian awakening.

There is confusion as to when the Battle of Kumanovo occurred. Currently there are two sources that historians possibly regard as the most accurate. Before the Ottomans could assemble a number of troops to head for Kumanovo, they firstly were required to take back the town of Kriva Palanka. The Ottoman Council of war organized a meeting and on the 14th of November, 1689 a number of generals and officers met in Ottoman Bulgaria. A decision was made in Sofia, and that the uprising or revolt leaders should be caught and executed. Eventually Kriva Palanka was taken again by the Ottoman armies, the remaining rebels had fled from the town as the town was set on fire. Karposh was preparing for yet another confrontation between him, his revolutionaries and the might of the Ottoman Empire. Little did Karposh know that the Ottoman army would call on re-inforcements from the Crimean Khanate to assist in the conflict up at Kumanovo. The tatars were part of the belligerents and they according to the Ottoman sultan assisted the Ottoman Empire as they were a very important Ottoman vassal.

With Karposh's arrival at the Kumanovo fortress, many of his revolutionaries were ordered to prepare the fortifications with cannons, gunpowder and ammunition. Unfortunately for the rebels, the current situation did not last long and a reversal in military and political events played a decisive role in the fate of the uprising.[3] With less than 150 men, the Macedonian rebels were not as ready as the Ottoman forces, as Karposh was preparing the fortress the Ottoman forces advanced upon the surrounding area. It is unclear as to how many troops the Ottoman garrison had, but it was most likely an estimated number of more than 2,000 soldiers were heading towards the Macedonian fortress. The Macedonian forces were outnumbered and their hopes at winning this battle was no good.

In order for the Ottoman army to attack they firstly had to use a number of ladders, and if this was unsuccessful then they would use a battering ram. A battering ram is a siege engine that is designed to break open the masonry walls of fortifications or break down wooden walls or gates. In the process the Ottoman army used their heavy cannons at breaking down the fortifications. Eventually the Ottoman army made a large gap and the fortifications were now useless, an Ottoman chronicler known as "Rashid" describes the situation of the battle : " The Macedonian revolutionaries eventually began galloping out of the fortress, with their horses even before the Ottoman army could come so close. Some were also seen running out of the fortress ready to do battle." Karposh was eventually captured by the Crimean tatars who also captured many other revolutionaries that were surrounded. They placed chains around Karposh's arms and he was taken to a prison - like wagon. Unfortunately this was the end of the Karposh's uprising. The chances of a free Macedonia was once again overcome by the large Ottoman army.

- ↑ Makedonskiot polk vo Ukraina, Aleksandar Matkovski, Skopje 1985

- ↑ Istorija na Makedonskiot Narod, Author : Stojanovski, 11:298-340, Institut za nacionalna istorija, Istorija na Makedonskiot Narod, I 294-5

- ↑ History of the Macedonian people - Ottoman rule in Macedonia, Author : Risto Stefov, Part 19 pp.1-35.