superman

English

WOTD – 26 October 2016

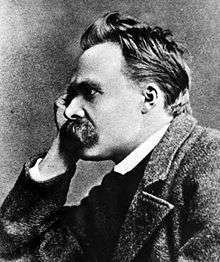

German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who introduced the term Übermensch in an 1883 work. The word was first translated into English as superman in the early 20th century.

Etymology

A calque of German Übermensch; super- + man. The German word was introduced by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) in his work Also sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 1883), and rendered in English as superman by Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) in the play Man and Superman (1903) and by Thomas Common (1850–1919) in his 1909 translation of Nietzsche’s work. Some scholars regard this word as not properly conveying the meaning of Übermensch, and prefer to use the German word or overman.

The “person of extraordinary powers” sense was reinforced by the DC Comics’ character Superman, who first appeared in Action Comics #1 dated June 1938.

Pronunciation

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /ˈs(j)uːpəmæn/

- (General American) IPA(key): /ˈsupɚmæn/

Audio (AU) (file) - Hyphenation: su‧per‧man

Noun

superman (plural supermen)

- (chiefly philosophy) An imagined superior type of human being representing a new stage of human development; an übermensch, an overman. [from 1903.]

- Nietzsche wrote of the coming of the superman.

- 1903, [George] Bernard Shaw, “Man's Objection to His Own Improvement”, in The Revolutionist's Handbook and Pocket Companion, appendix to Man and Superman: A Comedy and a Philosophy, Westminster, London: Archibald Constable & Co., Ltd., OCLC 903618586, page 194:

- Man does desire an ideal Superman with such energy as he can spare from his nutrition, and has in every age magnified the best living substitute for it he can find. His least incompetent general is set up as an Alexander; his King is the first gentleman in the world; his Pope is a saint. He is never without an array of human idols who are all nothing but sham Supermen.

- 1909, Friedrich Nietzsche; Thomas Common, transl., “Zarathustra's Prologue”, in Thus Spake Zarathustra; a Book for All and None (Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche; 4), Edinburgh, T. N. Foulis, OCLC 1210069; republished as Thus Spake Zarathustra, New York, N.Y.: The Modern Library, [1940s?], OCLC 11993131, page 6:

- And Zarathustra spake thus unto the people: / I teach you the Superman. Man is something that is to be surpassed. What have ye done to surpass man? / […] What is the ape to man? A laughing-stock, a thing of shame. And just the same shall man be to the Superman: a laughing-stock, a thing of shame.

- A person of extraordinary or seemingly superhuman powers.

- He worked like a superman to single-handedly complete the project on time.

- 1931, P[yotr] D[emianovich] Ouspensky; R[eginald] R. Merton, transl., “Superman”, in A New Model of the Universe: Principles of the Psychological Method in Its Application to Problems of Science, Religion, and Art, New York, N.Y.: Alfred A. Knopf, OCLC 1431250, pages 113–114:

- [page 113] The idea of superman is as old as the world. Through all the centuries, through hundreds of centuries of its history, humanity has lived with the idea of superman. Sayings and legends of all ancient peoples are full of images of a superman. Heroes of myths, Titans, demi-gods, Prometheus, who brought fire from heaven; prophets, messiahs and saints of all religions; heroes of fairy tales and epic songs, knights who rescue captive princesses, awake sleeping beauties, vanquish dragons, and fight giants and ogres—all these are images of a superman. […] [page 114] People dreamt of, or remembered times long past when their life was governed by supermen, who struggled against evil, upheld justice and acted as mediators between men and the Deity, governing them according to the will of the Deity, giving them laws, bringing them commandments.

- 2010 August, A[lex] E[chevarria] Roman, chapter 25, in The Superman Project: A Chico Santana Mystery, New York, N.Y.: Thomas Dunne Books, St. Martin's Press, →ISBN, page 218:

- I had a vision of what the ideal man should be. I wanted someone whose income combined with mine could afford us a family, an apartment, a car, and all the travel, luxury, and fun we could possibly tolerate. I wanted a Superman.

- 2016, Patrick J. Reider, “How Batman Cowed a God”, in Nicolas Michaud, editor, Batman, Superman, and Philosophy: Badass or Boyscout? (Popular Culture and Philosophy; 100), Chicago, Ill.: Open Court Publishing Company, →ISBN:

- What type of human weakness might a being of unfathomable power—a superman—inadvertently expose to the keen analytic mind of an avenging dark knight? Would he discover that a superhuman being who cannot be overcome, who is loved and adored by most, and who awes the commoner, desires to be overcome?

- 2016, A Study Guide for Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” (Novels for Students), Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale; Cengage Learning, →ISBN:

- Early in Crime and Punishment, [Rodion] Raskolnikov has become obsessed with the notion that he himself is a "superman." Therefore, he thinks, he is not subject to the laws that govern ordinary people. […] However, his indecision and confusion throughout the novel indicate that he is not a superman. Moreover, in the course of the novel, [Fyodor] Dostoyevsky seeks to prove that there is no such thing as a superman. Dostoyevsky believes that every human life is precious, and no one is entitled to kill.

Alternative forms

Antonyms

Translations

übermensch

|

|

person of extraordinary or superhuman powers

See also

Further reading

French

Pronunciation

- IPA(key): /sy.pɛʁ.man/

See also

- superwoman, superfemme, surfemme

- surhomme

Further reading

- “superman” in le Trésor de la langue française informatisé (The Digitized Treasury of the French Language).

Italian

This article is issued from

Wiktionary.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.