bandura

English

WOTD – 24 August 2019

Etymology

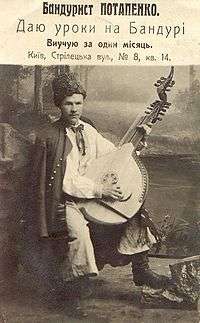

A Kharkiv-style bandura

Borrowed from Ukrainian банду́ра (bandúra), possibly through Italian pandura and Polish pandura, from Late Latin pandura (“musical instrument with three strings”), from Ancient Greek πανδοῦρα (pandoûra, “three-stringed lute; zither”), perhaps from Lydian.[1]

Pronunciation

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /bænˈduːɹə/

- (General American) IPA(key): /bænˈduɹə/

- Hyphenation: ban‧du‧ra

Noun

bandura (plural banduras)

- (music) A Ukrainian plucked stringed instrument with a tear-shaped body, like an asymmetrical lute or a vertical zither, which is played with both hands while held upright on the lap.

- 1871, [Nikolai Nikolaevich] Muraviev, “Return”, in Philipp Strahl and W[illiam] S[tephen] A[lexander] Lockhart, transl., Muraviev’s Journey to Khiva through the Turcoman Country, 1819–20. Translated from the Russian […]; and from the German […], Calcutta: Printed at the Foreign Department Press, […], OCLC 563009218, page 81:

- Shah Sanam was the lovely daughter of a very rich and eminent man. The young Karib, renowned for his song and his bandura, fell in love with her, and she, to test his faith, demanded that he should not approach her for seven years, but travel in foreign lands for that period. […] Time and travels have changed his features, and no one recognizes him. He touches the strings and pours forth a song descriptive of his live, his wanderings, his anguish, and is discovered by the magic tones of the bandura, his adventures, above all, by his voice and passionate fire. The joy of union now takes the place of the bitterness of separation. Shah Sanam falls into his arms, and papa agrees to confirm their bliss.

- 1886, Nikolaï Vasilievitch Gogol, chapter III, in Isabel F[lorence] Hapgood, transl., Taras Bulba [...] Translated from the Russian, New York, N.Y.: Thomas Y[oung] Crowell & Co. […], OCLC 7547528, page 75:

- The whole night passed amid shouts, songs, and rejoicings; and the rising moon gazed long at troops of musicians traversing the streets with bandouras, flutes, round balalaikas, and the church choir, who were kept in the Setch to sing in church and glorify the deeds of the Zaporozhtzi.

- 1887, Vladímir Korolénko, “The Forest Soughs. A Forest Legend.”, in Aline Delano, transl., The Vagrant and Other Tales [...] Translated from the Russian, New York, N.Y.: Thomas Y[oung] Crowell & Co. […], OCLC 2400165, page 50:

- They say that bandura-players are growing scarce; that they are no longer to be found at fairs. I have an old bandura hanging up on the wall in the hut. Opanás taught me to play on it, but there is no one to play it after me; and when I die, and that may be soon, perhaps nowhere in the wide world will one be found to play the bandura.

- 1913, Bernard Pares, Maurice Baring, and Samuel N[orthrup] Harper, editors, The Russian Review: A Quarterly Review of Russian History, Politics, Economics and Literature, volume 2, Paris; New York, N.Y.: Thomas Nelson and Sons, OCLC 863808856, page 177:

- 'Thank you, master, for your lesson. I will sing you a song if you will listen;' and he touched a string of the bandura.

- 1988, Commission on the Ukraine Famine, quoting Oleksander Honcharenko, interviewee, “Appendix I: Translations of Selected Oral Histories [Case History LH38: Translated from Ukrainian by Darian Diachok]”, in Investigation of the Ukrainian Famine 1932–1933: Report to Congress […], Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, OCLC 20596207, page 337:

- It was only at this time that bandura players emerged from underground. They had been banned from playing under the Tsar, and then they emerged and began to remind everyone openly about their Cossack past and to awaken feelings of nationalism in young children. […] Once, it was in 1922, in the village of Ol'shanytsia, he walked into our classroom, played several songs and then explained what kind of instrument the bandura was, where it had come from, how long it had been in existence, and how it had been a pleasant diversion in the Cossack encampments of the past. We became quite interested in the bandura for its beautiful, pleasant sound and its fine timber. Afterwards, when we came home, the first thing we set out to do was make our own banduas.

- 1997, David [Benedict] Reck, Music of the Whole Earth, New York, N.Y.: Da Capo Press, →ISBN, page 133:

- In the Ukraine of Russia the large bandoura with its almost circular face and as many as thirty strings (combining a zither function with fingered lute technique) is a popular short-necked lute, […]

- 1999 November, Alexis Kochan; Julian Kytasty, “Ukraine: The Bandura Played On”, in Simon Broughton, Mark Ellingham, and Richard Trillo, with Orla Duane and Vanessa Dowell, editors, World Music: Volume 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East (The Rough Guide), London: Rough Guides, published October 2000, →ISBN, page 309:

- The bandura, a kind of zither, is unique to Ukraine and is considered the national instrument. Unlike the Scandinavian and Baltic zithers, it is plucked held upright and has a lute-like neck for the longest bass strings. The bandura owes its position in Ukrainian culture to its association with a tradition of epic songs – dumy – that survived into the twentieth century.

- 2007, John Radzilowski, “Bringing Ukrainian Traditions to North America”, in Robert D. Johnston, editor, Ukrainian Americans (The New Immigrants), New York, N.Y.: Chelsea House, Infobase Publishing, →ISBN, page 91:

- The bandura is a stringed instrument with an ancient history. Early forms of the bandura existed as far back as the sixth century. Modern banduras come in several forms with 20 to 65 strings. The classical bandura is tuned diatonically and has 20 strings and wooden pegs; the Kharkiv bandura is tuned diatonically or chromatically and has a single string mechanism and 34 to 65 strings; and the Kyiv bandura, which has 55 to 64 strings, is tuned chromatically.

-

Alternative forms

Derived terms

Translations

Ukrainian plucked stringed instrument

See also

- Appendix:Glossary of chordophones

References

- Melʹnyčuk O. S., editor (1982–2012), “бандура”, in Etymolohičnyj slovnyk ukrajinsʹkoji movy [Etymological Dictionary of the Ukrainian Language] (in Ukrainian), Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

This article is issued from

Wiktionary.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.