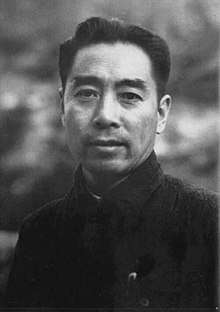

Zhou Enlai (5 March 1898 – 8 January, 1976), a prominent Chinese Communist leader, was the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, from 1949 until his death.

Quotes

- All diplomacy is a continuation of war by other means.

- As quoted in Saturday Evening Post (27 March 1954); this is a play upon the famous maxim of Clausewitz: "War is the continuation of politics by other means".

- For us, it is all right if the talks succeed, and it is all right if they fail.

- On President Richard Nixon’s visit to China (5 October 1971), as quoted in Simpson's Contemporary Quotations (1988) edited by James Beasley Simpson

- China is an attractive piece of meat coveted by all … but very tough, and for years no one has been able to bite into it.

- To the Chinese Communist Party Congress, as quoted in The New York Times (1 September 1973)

- We shall use only peaceful means and we shall not permit any other kind of method.

- Concluding his summary of his government’s approach to boundary settlement at Bandung, with a pledge and a warning, as quoted in "How the Sino-Russian Boundary Conflict Was Finally Settled : From Nerchinsk 1689 to Vladivostok 2005 via Zhenbao Island 1969" by Neville Maxwell

- It is too soon to say.

- Often thought to refer to the significance of the French Revolution of 1789, it has been argued that he was actually indicating the French protests of 1968, as quoted in "Zhou’s cryptic caution lost in translation" by Richard McGregor in Financial Times (10 June 2011)

Disputed

- The more troops they send to Vietnam, the happier we will be, for we feel that we shall have them in our power, we can have their blood. So if you want to help the Vietnamese you should encourage the Americans to throw more and more soldiers into Vietnam. We want them there. They will be close to China. And they will be in our grasp. They will be so close to us, they will be our hostages. … We are planting the best kind of opium especially for the American soldiers in Vietnam.

- Reported in Christian Crusade Weekly (March 3, 1974) as having been said be Zhou to Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1965; reported as a likely misattribution in Paul F. Boller, Jr., and John George, They Never Said It: A Book of Fake Quotes, Misquotes, & Misleading Attributions (1989), p. 133.

Quotes about Zhou

Chou En-lai to me appears as the most superior brain I have so far met in the field of foreign politics… ~ Dag Hammarskjöld

- Sorted alphabetically by author or source

- There is nothing to suggest that Zhou was filled with blood lust, enjoyed killing supposed counter-revolutionaries, plotted to imprison tens of millions of regime opponents, or was indifferent to the mass starvation and hardship around him. Indeed, he counseled colleagues and protected them, to the degree possible, from the madness of the Cultural Revolution, essentially an intra-party civil war which ruined the lives of millions of people, including many loyal communist apparatchiks. Like Stalin’s purges, the Cultural Revolution was bloody — estimates of the number of dead start at around 500,000 and top out at three million — and was no less mad, convulsing China for years.

Throughout everything, however, Zhou acted as Mao’s chief retainer, a state functionary who helped turn his impoverished nation into a vast prison camp. To have resisted obviously would have been dangerous, but Zhou’s influence within the party was enormous and he could have allied with other critics of Mao, especially after the evident disaster of the Great Leap Forward. But to do so would have been risky, and risk was something Zhou avoided at all costs. … He seemed to embody a sense of personal decency, treating his family, friends, and colleagues well, in contrast to the vindictive, licentious, and unpredictable Mao. Zhou also sought prosperity and stability for China — a communist China, to be sure, but nevertheless one in which people would no longer be starving. A perception that Zhou cared about those ruled by Beijing generated spontaneous popular mourning after his death, even though Mao did not attend the funeral.

- As a student of acting, he knew how to master the role he was handed. For years, he had been performing the important part of the indispensable servant to perfection, much to the annoyance of Mao, his master. He was almost entirely self-effacing. He knew how to mend the broken pieces of crockery that Mao shattered from time to time. Zhou’s genius for self-abnegation and the deft and artful way that he had of cleaning up a nasty mess aggravated Mao, the master, and piqued his pride. They were the odd couple, but this was no domestic comedy.

- Gao Wenqian, in Zhou Enlai: The Last Perfect Revolutionary (2007)

- It is a little bit humiliating when I have to say that Chou En-lai to me appears as the most superior brain I have so far met in the field of foreign politics... so much more dangerous than you imagine because he is so much better a man than you have ever admitted.

- Dag Hammarskjöld, in a letter to a friend, as quoted in Hammarskjöld (1972) by Brian Urquhart

- Mao dominated any gathering; Zhou suffused it. Mao's passion strove to overwhelm opposition; Zhou's intellect would seek to persuade or outmaneuver it. Mao was sardonic; Zhou penetrating. Mao thought of himself as a philosopher; Zhou saw his role as an administrator or a negotiator. Mao was eager to accelerate history; Zhou was content to exploit its currents.

- Henry Kissinger, in On China (2011)

- He's the truest friend I've ever had. What's more, he's an exquisite man, full of kindness and sophistication, the most aristocratic aristocrat one can meet. To those who can't understand how I, a non-communist, could be friends with Zhou Enlai, I say: "But he's a prince more princely than I am!"

- Norodom Sihanouk, as quoted in interview with Oriana Fallaci (June 1973), published in Intervista con la Storia (sixth edition, 2011), p. 109

- Through the ups and downs of the unpredictable Chinese Revolution, Zhou Enlai’s reputation has seemed to stand untarnished. The reasons for this are in part old-fashioned ones: in a world of violent change, not noted for its finesse, Zhou Enlai stood out as elegant, courteous, even courtly; and with his remarkable good looks and fluent intelligence, he seemed to personify the mannerisms of diplomats from a gentler age. At the same time, Zhou’s reputation benefited from the apparently profound contrasts with Mao Zedong, who loved to thrust himself forward into the limelight, and never shrank from taking credit for China’s perpetual upheavals.

The title of Gao Wenqian’s book, Zhou Enlai: The Last Perfect Revolutionary, is deliberately sardonic, and is designed to show that far from being perfect, Zhou was in fact fallible, often devious, and capable of great cruelty to his friends and fellow revolutionaries.

External links

- Zhou Enlai Biography From Spartacus Educational

- Zhou Enlai, Stephan Landserger's Chinese Propaganda Pages

- "The Mystery of Zhou Enlai" by Jonathan Spence, reviewed in The New York Review of Books

- Interview with Zhou En Lai (1965)

- Zhou Enlai on IMDb

- Works by or about Zhou Enlai in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

This article is issued from

Wikiquote.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.