There are no great men, there are only great challenges that ordinary men are forced by circumstances to meet.

Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey, Jr., GBE (October 30, 1882 – August 16, 1959) (commonly referred to as "Bill" or "Bull" Halsey), was an American Fleet Admiral in the United States Navy. He commanded the South Pacific Area during the early stages of the Pacific War against Japan. Later he was commander of the Third Fleet through the duration of hostilities.

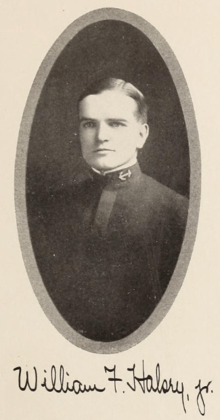

Midshipman William F. Halsey, Jr

Admiral William F. Halsey

This is Blackjack himself. Your work so far has been superb. I expect even more. Keep the bastards dying!

Quotes

- Dear Ernie,

It has been an education, and a very pleasant one, to serve under you this past winter. May I thank you for your patience of me personally and for the professional lessons you have given me- I should be proud to serve under you any time- anywhere, & under any conditions. The best of luck always- may your new job be to your liking- and here's hoping for more stars afloat.

Always sincerely yours,

Bill Halsey.- Handwritten note from Halsey to Ernest King on 22 June 1939, as quoted by Walter R. Borneman in The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy, and King: The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea (2012), p. 180

- Before we're through with them, the Japanese language will be spoken only in hell.

- Remark in December 1941, after the attack of Pearl Harbor, as quoted in Roger Parkinson, Attack on Pearl Harbour (1973), p. 117; James Bradley, Flyboys (2004), p. 138.

- Never before in the history of warfare has there been a more convincing example of the effectiveness of sea power than when, despite this undefeated, well armed, and highly efficient army, Japan surrendered her homeland unconditionally to the enemy without even a token resistance. The devastation wrought by past bombings plus the destruction of the atomic bombs spelled nothing less than the extinction of Japan. The bases from which these attacks were launched- Saipan, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa- were to have been the spring boards for the mightiest sea-borne invasion yet conceived by man. The "fighting fleets" of the United States which had made possible every invasion victory for America were ready and waiting. The Japanese had two alternatives; to fight and face destruction, or to surrender. The Imperial Japanese Empire chose to surrender.

- Battle Stations! Your Navy in Action (1946), "The Surrender of Japan", p. 360

- There are no great men, there are only great challenges, which ordinary men like you and me are forced by circumstances to meet.

- Quoted in the Congressional Record, 11 December 1971.

- Missing the Battle of Midway has been the greatest disappointment of my career, but I am going back to the Pacific where I intend personally to have a crack at those yellow bellied sons of bitches and their carriers.

- Speech at the Naval Academy, as quoted in James C. Bradford, Quarterdeck and Bridge: Two Centuries of American Naval Leaders (1997), p. 350.

- Kill Japs, kill Japs, kill more Japs!

- Reported in James Bradley, Flyboys (2004), p. 138; Thomas Evans, Sea of Thunder (2006), p. 1; Paul Fussell, Wartime (1990), p. 119.

Admiral Halsey's Story (1947)

- This book was co-written by Halsey and J. Bryan, III, the latter of whom wrote the introduction. The rest of the book is written from Halsey's point of view.

- I'll take it! If anything gets in my way, we'll shoot first and argue afterwards.

- p. 76.

- This is Blackjack himself. Your work so far has been superb. I expect even more. Keep the bastards dying!

- p. 242

Quotes about Halsey

- Alphabetized by author

Halsey was dubbed "Bull" by the press, but he hated that nickname as much as he hated all pretense and showmanship. What he did not hate, he loved, and chief among the latter were his men. ~George M. Hall

- FLEET ADMIRAL WILLIAM FREDERICK HALSEY, JR., USN. Born New Jersey 1882. Annapolis Class of 1904. First command, USS DuPont, 1909. Commanded USS Flusser, 1912; Jarvis, 1913. Awarded Navy Cross, 1918, for services as Comdr., USS's Benham and Shaw. Commanded USS Saratoga, 1935-7. As Rear Admiral, commanded Carrier Divisions 2 and 1, 1938-9. Designated Comdr., Aircraft, Battle Force, 1940. Awarded DSM, 1942, as Comdr., Marshall Raiding Force. Appointed Comdr., South Pacific Force, Oct. 1942. Awarded Army DSM, second Navy DSM for services, 1942-4. Assumed command famous Third Fleet, 1944; won third, fourth Navy DSM's for services, 1944-5. Holds numerous foreign Decorations. On Dec. 11, 1945, achieved highest rank, Fleet Admiral.

- Biographical Notes on Halsey in Battle Stations! Your Navy in Action (1946), p. 396

- The only man in the class who can compete with General in the number of offices he has held. Started out in life to become a doctor and in the process gained several useful hints. Honorary member of the S.P.C.A. for having so many times saved Shutuby from persecution. A real old salt. Looks like a figurehead of Neptune. Strong sympathizer with the Y.M.C.A. movement. Everybody's friend and Brad's devoted better half.

- Description of Halsey in Lucky Bag (1904), yearbook of the United States Naval Academy, p. 41

- William F. Halsey, Jr., wasn't destined for academic stardom at the Naval Academy, but he applied himself just enough to make respectable marks without adversely affecting his preferred social and athletic pursuits. Once, when Halsey came dangerously close to failing theoretical mechanics, his father strongly advised him to drop football. That, of course, was out of the question. Instead, Bill recruited the scholars in his class to tutor him and a few others similarly challenged. When the exam was over, Bill went to his father's quarters for lunch and was immediately asked if the results had been posted. "Yes, sir," Bill answered, and then reported that he had made 3.98 out of 4.0. His father stared at him for a full minute and finally asked incredulously, "Sir, have you been drinking?"

- Walter R. Borneman, The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy and King- The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea (2012), p. 45

- King was never shy about promoting his talents, but despite his role as COMINCH, it was Nimitz and his principal deputies who got more press attention. And while King usually held the respect of even his critics, he was simply too aloof and lacked the likability and follow-you-anywhere personality that radiated from both Nimitz and Halsey. From Nimitz, it came from studied calm; Halsey's resulted more from his volcanic "hit em again harder" football mentality. If Marshall and King had agreed on only one thing, it would have been that each of them had their public heroes to nurture and attempt to control: MacArthur for Marshall and Halsey for King. And in the end, it was this recognition of Halsey's place in the public consciousness that seems to have tipped King from Spruance to Halsey in recommending that fourth set of five stars. Halsey was too much of an institution in the American press to be denied. Had Spruance been of a similar ilk as Halsey and sought the spotlight rather than shunned it, the result might have been different. As it was, Spruance passed off attempts to be called the hero of Midway by recognizing the staff he had inherited from Halsey and Frank Jack Fletcher's commanding role.

- Walter R. Borneman, The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy and King- The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea (2012), p. 416

- Heat-of-battle decisions at Leyte and typhoons aside, it is difficult to argue that Bill Halsey didn't deserve the five stars of a fleet admiral, although with King's procrastination, he didn't receive them until December 11, 1945. But there is convincing evidence that of the remaining American admirals of World War II, Raymond A. Spruance was no less deserving of five stars than Halsey. Indeed, with the exception of Spruance, it is difficult to imagine another of their contemporaries on the same level as Leahy, King, Nimitz, and Halsey. In 1950, Congress resolved a similar dilemma in the army when it accorded Omar Bradley a fifth set of army five stars, in part for his postwar role. It could have done Spruance similar justice by making a similar provision for the navy.

- Walter R. Borneman, The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy and King- The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea (2012), p. 417

- Even after they were checked at Midway and Guadalcanal in 1942, many Japanese remained convinced that the Anglo-American enemy was indeed psychologically incapable of recovering In actuality, the contrary was true, for the surprise attack provoked a rage bordering on the genocidal among Americans. Thus, Admiral William Halsey, soon to become commander of the South Pacific Force, vowed after Pearl Harbor that by the end of the war the Japanese language would be spoken only in hell, and rallied his men thereafter under such slogans as "Kill Japs, kill Japs, kill more Jap." Or as the U.S. Marines put it in a well-known variation on Halsey's motto: "Remember Pearl Harbor- keep 'em dying."

- John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War (1986), p. 37

- Indeed, in wartime jargon, the notion of "good Japanese" came to take on an entirely different meaning than that of "good Germans," as Admiral William F. Halsey emphasized at a news conference early in 1944. "The only good Jap is a Jap who's been dead for six months," the commander of the U.S. South Pacific Force declared, and he did not mean just combatants. "When we get to Tokyo, where we're bound to get eventually," Halsey went on, "we'll have a little celebration where Tokyo was." Halsey was improvising on a popular wartime saying, "the only good Jap is a dead Jap," and his colleagues in the military often endorsed this sentiment in their own fashion.

- John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War (1986), p. 79

- Among the Allied war leaders, Admiral Halsey was the most notorious for making outrageous and virulently racist remarks about the Japanese enemy in public. Many of his slogans and pronouncements bordered on advocacy of genocide. Although he came under criticism for his intemperate remarks, and was even accused of being drunk in public, Halsey was immensely popular among his men and naturally attracted good press coverage. His favorite phrase for the Japanese was "yellow bastards," and in general he found the color allusion irresistible.

- John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War (1986), p. 85

- Simian metaphors, however, ran a close second in his diatribes. Even in his postwar memoirs, Halsey described the Japanese as "stupid animals" and referred to them as "monkeymen." During the war he spoke of the "yellow monkeys," and in one outburst declared that he was "rarin' to go on a new naval operation "to go get some more Monkey meat." He also told a news conference in early 1945 that he believed the "Chinese proverb" about the origin of the Japanese race, according to which "the Japanese were a product of mating between female apes and the worst Chinese criminals who had been banished from China by a benevolent emperor." These comments were naturally picked up in Japan, as Halsey fully intended them to be, and on occasion prompted lame responses in kind. A Japanese propaganda broadcast, for example, referred to the white Allies as "albino apes." Halsey's well-publicized comment, after the Japanese Navy had been placed on the defensive, that "the Japs are losing their grip, even with their tails" led a zookeeper in Tokyo to announce he was keeping a cage in the monkey house reserved for the admiral.

- John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War (1986), p. 85

- Shortly before the Pearl Harbor attack his CarDiv was returning from delivering aircraft to Wake Island, already on full war alert (Halsey was one of several officers who understood the meaning of "this is considered to be a war warning"). During the war he had an active, varied, and distinguished career: the raids on the Mandates, the Doolittle Raid, the Guadalcanal Campaign, the Solomons Campaign, and finally as leader of the Third Fleet in the Central Pacific. After the war he retired as a fleet admiral, and entered business. Shortly before his death he led an ultimately futile campaign to preserve the carrier Enterprise as a war memorial. Halsey was a tough, aggressive officer who made surprisingly few mistakes (the most glaring being his failure to adequately cover the "jeep carriers" off Samar during the Battle of Leyte Gulf).

- James F. Dunnigan & Albert A. Nofi, The Pacific War Encyclopedia, Volume 1: A-L (1998), p. 260-261

- Behind the sixty-year-old admiral was a distinguished career first in destroyers and latterly as a carrier commander. His more than medium height, broad shoulders, and barrel chest gave him a strong presence and "a wide mouth held tight and turned down at the corners and exceedingly bushy eyebrows gave his face, in a grizzled sea dog way, an appearance of good humor." He was not so impulsive as the nickname "Bull" (which was not used by his friends) suggested, but he always displayed a certain indifference to detail that looked like carelessness.

- Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (1990), p. 335

- Although agreeing with Ghormley's current dispositions, within hours of taking command Halsey put his personal stamp on operations. First he simply seized a headquarters ashore from sensitive Free French officials whom Ghormley had never confronted, despite desperate conditions of crowding on Argonne. Within forty-eight hours he scuttled the Ndeni operation, as should have been done weeks before. But this same day Halsey was forcefully reminded of one of the sources of displeasure with Ghormley's stewardship when I-176 torpedoed heavy cruiser Chester in the stretch of waters frequented by American task forces called "Torpedo Junction", in a wry play upon the title of the popular song "Tuxedo Junction". On his third day in command, Halsey decided to move the main fleet base from Auckland to Noumea, and he did not merely ask for but demanded a million square feet of covered storage space.

- Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (1990), p. 335

- One simple order revealed more about his attitude than any rhetorical flourish: henceforth naval officers in the South Pacific would remove ties from tropical uniforms. Halsey said he gave this order to conform to Army practice and for comfort, but to his command it viscerally evoked the image of a Brawler stripping for action and symbolized a casting off of effete elegance no more appropriate to the tropics than to war. His national popularity would endure, but later events would put his effectiveness into serious doubt. Indeed, one of his ablest subordinates would observe that by 1944 "the war simply became too complicated for Halsey." But in mid-October 1942 with his country at bay and locked in mortal combat with a relentless foe, Halsey was in his element. Within one week of taking command, Halsey sent an order to Admiral Kinkaid that would electrify the entire Navy: "Strike, repeat, strike."

- Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (1990), p. 335-336

- While in Pensacola, Halsey earned what was known as "the flying jackass" award. Whenever a pilot taxied over a runway light, he was obliged to wear a piece of medal shaped like a jackass across his chest except when actually flying, at least until the next student earned it. Although he was a captain among mostly ensigns, he wore the jackass without complaint. When he time came to pass it on, he took it off but declined to part with it. He said: "I want to keep it. When I take command of the Saratoga, I'm going to put it on the bulkhead of my cabin. If anybody aboard does anything stupid, I'll take a look at the jackass before I ball him out and say to myself 'Wait a minute, Bill Halsey, you're not so damn good yourself.'"

- George M. Hall, The Fifth Star: High Command in an Era of Global War (1994), p. 108

- In time, Halsey was moved up to commander of the entire Pacific-fleet carrier force- coupled with a promotion to vice admiral. It was in this capacity that he sailed into Pearl Harbor shortly after the Japanese attack and began to emerge from an obscure officer into the most popular admiral in American history. Simply put, he was a natural fighter- at the only time in the history of the United States Navy that there was a prolonged struggle in an ocean-based theater of war.

- George M. Hall, The Fifth Star: High Command in an Era of Global War (1994), p. 108

- Halsey immediately conducted raids on a few of the outermost Japanese-held islands. The actual damage was not great, but it put Japan on notice that the United States was assuming the offensive. He also accepted the carrier support mission for the famed Doolittle raid over Tokyo in April 1942. The raid was a grave risk, not only to Halsey but to the U.S. fleet. If the fleet were spotted by the Japanese- which is what happened- and then sunk, it would have left the United States with only two carriers. Halsey's adroit maneuver tactics during the withdrawal avoided those consequences. However, the successful raid and subsequent getaway motivated the Japanese to attempt to put the American fleet out of action once and for all. To do this, they planned a decisive battle near Midway, and Halsey itched for it. Unfortunately he had to give priority to another type of itch, this one a dermatitis so painful that he was hospitalized for several months. The disappointment planted a seed that would later engender serious problems at Leyte Gulf.

- George M. Hall, The Fifth Star: High Command in an Era of Global War (1994), p. 108-109

- In the interim, Halsey was sent on an inspection trip of the Southwest Pacific, or so he thought. At the time, the navy and marine corps were fighting desperately to retain their toehold on Guadalcanal and thus prevent the Japanese from cutting their line of communications from the United States to New Zealand and Australia. As mentioned in previous chapters, the commander of this mission, Admiral Ghormley, was not up to the job. So just as Halsey's seaplane landed at Ghormley's headquarters, Halsey was handed a classified message telling him to assume command immediately. Morale shot up, and sailors were sometimes overheard arguing whether Halsey was worth two or three carriers. That hyperbole is not as fanciful as it seems and comes under the expression "leadership as a combat force multiplier." A competent admiral will make much better use of his fleet, inflict more damage on his opponent, and suffer less damage to his own. Hence, in a very real way, Halsey was worth a carrier or two, if not three. It all depends on the consideration given to the factor of time. This is not to say that his leadership in the Solomons was perfect. He lost too many ships in various tactical battles without exacting a commensurate price on the Japanese. Yet like Grant at the Battle of the Wilderness, he persevered and that meant success.

- George M. Hall, The Fifth Star: High Command in an Era of Global War (1994), p. 109

- Halsey was dubbed "Bull" by the press, but he hated that nickname as much as he hated all pretense and showmanship. What he did not hate, he loved, and chief among the latter were his men.

- George M. Hall, The Fifth Star: High Command in an Era of Global War (1994), p. 111

- On the afternoon of 28 February 1939 King and Halsey went together on board Houston where some twenty or more flag officers of the United States Fleet had been summoned to pay their respects to the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy. President Roosevelt was in high spirits, for he loved the Navy and always visibly expanded when at sea. As the admirals greeted him, he would have some pleasant, half-teasing personal message for each. King, when his turn came, shook hands and said that he hoped the President liked the manner in which naval aviation was improving month by month, if not day by day. Mr. Roosevelt seemed pleased by this, and, after a brief chat, admonished King, in his bantering way, to watch out for the Japanese and the Germans. King made no attempt to hold further conversation with the President, even though Admiral Bloch urged him to do so. He had never "greased" anyone during his forty-two years of service and did not propose to begin, particularly at a moment when many of the admirals were trying so hard to please Mr. Roosevelt that it was obvious. He had paid his respects civilly; he was in plain sight, and felt that the President could easily summon him if there were anything more to say. He believed that his record would speak for itself, and that it was not likely to be improved by anything that he might say at this moment. It seemed that the die was already cast, although the President's decision would not be made known for some weeks.

- Ernest King and Walter M. Whitehill, Fleet Admiral King: A Naval Record (1952), p. 291-292

- World War II gave King the opportunity of putting in practice another conviction. His earliest studies of the Napoleonic campaigns had indicated to him that the great weakness of the French military system of the period was that it required the detailed supervision of Napoleon. His belief that one must do the opposite, and train subordinates for independent action, had been confirmed and strengthened through his years of association with Admiral Mayo. During World War II King would jokingly maintain that he managed to keep well by "doing nothing that I can get anybody to do for me," but in all seriousness he could not have survived the four years of war without having made full use of the decentralization of authority into the hands of subordinate commanders, who were considered competent unless they proved themselves otherwise, and who were expected to think, decide, and act for themselves. Upon Nimitz in the Pacific, Edwards, Cooke and Horne in Washington, Ingersoll in the Atlantic, Stark in London, Halsey, Spruance, Kinkaid, Hewitt, Ingram and many other flag officers at sea, King relied with confidence and was not disappointed.

- Ernest King and Walter M. Whitehill, Fleet Admiral King: A Naval Record (1952), p. 645

- History gives us ample precedence for making decisions at the speed of relevance. In 1941, General Douglas MacArthur was planning a landing in the Southwest Pacific. He wrote to Admiral William Halsey, in charge of the South Pacific, asking for a naval campaign to divert the Japanese forces. Only two days later, Halsey wrote back, pledging his support. There was no need for extended exchanges between staffs. The shared objective was to shatter the Japanese forces. All else was secondary. Two strong-willed commanders collaborated to unleash hell upon the enemy.

- James Mattis, Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead (2019), p. 57-58

- Halsey, the public's favorite in the Navy, will always remain a controversial figure, but none can deny that he was a great leader; one with the true "Nelson touch." His appointment as commander South Pacific Force at the darkest moment of the Guadalcanal campaign lifted the hearts of every officer and bluejacket. He hated the enemy with an unholy wrath, and turned that feeling into a grim determination by all hands to step up to hit hard, again and again, and win. His proposal to step up the Leyte operation by two months was a stroke of strategic genius which undoubtedly shortened the Pacific war. Unfortunately, in his efforts to build public morale in America and Australia, Halsey did what Spruance refused to do- built up an image of himself as an exponent of Danton's famous principle, "Audacity, more audacity, always audacity." That was the real reason for his fumble in the Battle for Leyte Gulf. For his inspiring leadership in 1942-1943, his generosity to others, his capacity for choosing the right men for his staff, Halsey well earned his five stars, and his place among the Navy's immortals.

- Samuel Eliot Morison, The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (1963), p. 582

- On Wednesday, January 7, the Enterprise force returned to Pearl from patrol, and its commander, crusty warrior Vice Admiral Halsey, came ashore. Halsey's ferocious scowl, which announced to all that he hated the enemy like sin, could not conceal the twinkle in his eye that bespoke his affection for his fellow sailors, particularly those who served under him. We lack eyewitness records of what happened next, but we know that Halsey barged into the CincCPac conference that day or the next and cleared the air by sounding off loudly, and no doubt profanely, against the defeatism he found. He then and there permanently endeared himself to his commander in chief by backing him and his raiding plan to the hilt. Because he was a vice admiral and Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force, and was liked and respected by all, his words carried decisive weight. Long afterward, when Halsey came under criticism, Nimitz recalled this difficult period and refused to participate in the general censure. "Bill Halsey came to my support and offered to lead the attack," he said. "I'll not be party to any enterprise that can hurt the reputation of a man like that."

- E.B. Potter, in Nimitz (1976), p. 288-289

- William F. Halsey was Commander of the South Pacific Fleet and the war's most colorful admiral.

- C.L. Sulzberger, in his book The American Heritage Picture History of World War II (1966), p. 335

- Halsey was a navy junior who spent three boyhood years at the academy while his father was an instructor there. His application for appointment was automatic.

- Jack Sweetman, The United States Naval Academy: An Illustrated History (1995), 2nd Edition, edited by Thomas J. Cutler, p. 150

- Halsey, who belonged to the last class to enter the academy less than 100 strong, was the most athletic [of the future five-star admirals]. A winner of the Thompson Trophy Cup, he was elected president of the Midshipmen's Athletic Association and was the starting fullback on the Navy teams of 1902 and 1903. In later life he liked to say he was the poorest fullback on the poorest teams Navy ever produced (their two-year record was 8-14). He also took an active part in class activities, serving on the class supper, crest, Christmas card, graduation ball, and cotillion committees. He was less active in the classroom and finished forty-third of sixty-seven, wearing the stripes of Second Battalion adjutant. At graduation, the academy's chief master-at-arms congratulated him with the words, "I wish you all the best luck in the world, Mr. Halsey, but you'll never be as good a naval officer as your father!"

- Jack Sweetman, The United States Naval Academy: An Illustrated History (1995), 2nd Edition, edited by Thomas J. Cutler, p. 152

External links

This article is issued from

Wikiquote.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.