The Spanish Civil War (Spanish: Guerra Civil Española) took place from 1936 to 1939. Republicans loyal to the left-wing Second Spanish Republic, in alliance with the anarchists, socialists and communists, fought against the Nationalists, in alliance with the Carlists, Catholics, Falangists and Aristocrats led by General Francisco Franco. The Nationalists won the war in early 1939 and ruled Spain until Franco's death in November 1975.

Top left: Members of the International Brigade Top right: Nationalist BF-109A Middle left: HMS Royal Oak Middle right: Bombings in Spanish West Africa Bottom left: Nationalist soldiers at the Battle of Madrid Bottom right: Republican soldiers at the Siege of the Alcázar of Toledo.

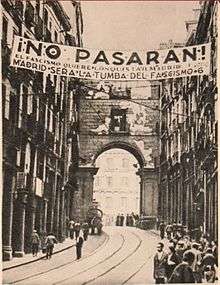

¡No pasarán! (They shall not pass!) Republican banner in Madrid reading "Fascism wants to conquer Madrid. Madrid shall be fascism's grave." during the siege of 1936–1939.

Republican forces during the Battle of Irún in 1936.

Members of the Condor Legion, a unit composed of volunteers from the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) and from the German Army (Heer) training in Ávila.

They gave up everything, their homes, their country, home and fortune- fathers, mothers, wives, brothers, sisters and children, and they came and told us: "We are here, your cause, Spain's cause, is ours." ~ Isidora Dolores Ibárruri Gómez

Junkers Ju-87A of the Condor Legion over Spain.

Early flag of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion

Francisco Franco in 1930

Say of them,

They are no longer young, they never learned

The arts, the stealth of peace, this peace, the tricks of fear;

And what they knew, they know

And what they dared they dare. ~ Genevieve Taggard

They are no longer young, they never learned

The arts, the stealth of peace, this peace, the tricks of fear;

And what they knew, they know

And what they dared they dare. ~ Genevieve Taggard

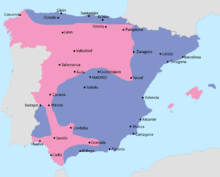

Map of the Spanish Civil War in September 1936; Republican territory = Blue; Nationalist territory = Pink.

Ruins of Guernica after the bombing, 31 December 1936.

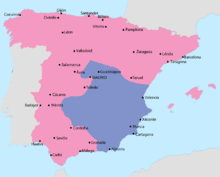

Map of the Spanish Civil War in February 1939; Republican territory = Blue; Nationalist territory = Pink.

Heinkel He-111 of the Condor Legion between bombing missions.

The cruiser Almirante Cervera, a key part of the Nationalist fleet

Quotes

- Those Americans who went to Spain to fight Franco and stave off World War II have never minded being called "premature anti-fascists." They were proud of the label.

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of Americans in Spain (1939), Foreword to the 1954 reprint.

- We have long memories. We have developed a relative immunity to the endless barrage of propaganda, slander and outright lies that has been laid upon us. And especially, we are immune to the Big Lie that destroyed Spain and which Hitler developed to such a point of perfection that it was necessary for millions of human beings to die to achieve the defeat of the Axis. Yet the Big Lie survives and flourishes mightily in our own country today. As it is promulgated daily, hourly and every minute of the day through every medium of communication, so it must be answered- until our own people see it for what it is and explode it in their own good time.

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of Americans in Spain (1939), Foreword to the 1954 reprint.

- Whenever we hear it said that Communism threatens us from within and without; whenever we are told that the Soviet Union menaces our "way of life" and wants to conquer the world; whenever we are summoned to a Holy Crusade that- if it is allowed to begin- will ravish the entire earth, we recall the following simple facts of history:

- Mussolini killed whatever democracy existed in Italy by claiming that Italy was threatened by Communism;

- Hitler destroyed the German Republic with the same weapon;

- Tojo broke the resistance of the people of Japan by using the identical thesis;

- Franco murdered the Spanish Republic in the name of the "Red menace";

- The Axis launched World War II under the slogan of saving the world from Communism.

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of Americans in Spain (1939), Foreword to the 1954 reprint.

- Here were students, dock-workers, clerks and labor-organizers, farmers. Most were unacquainted with each other, but they came together now with the warmth and familiarity of old friends; they told each other of their work in their respective countries; of their friends and families. They spoke of the European political scene, of the imperative necessity for the Loyalist Government to drive the foreign invader from Spain; you felt that with each of them, no matter how diverse his previous training, the Spanish struggle was a personal issue, something deep and close. This in itself, considering the disparity of their origin, was a major political phenomenon. They spoke no word of the actual business of war; they did not speculate on the nature of artillery or air attacks, of machine-gun fire. You felt: many of these men will never see their friends or families again; they don't know what they're getting into; their idealism has blinded them to the reality of what they will have to face. And you knew immediately that you were wrong; that they were so far from being blind that it might be said of them that they were among the first soldiers in the history of the world who really knew what they were about, what they were going to fight for- and that they were ready and eager to fight. Their very presence on the French frontier was an earnest of their understanding and their clarity; no one had made them come, no force but an inner force had brought them.

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of Americans in Spain (1939), p. 13

- "Bring us Franco's balls!" the men shouted. "'e ain't got no bloody balls," a voice replied.

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of Americans in Spain (1939), p. 63

- "You know what I got half a mind to do?" the driver said. "What?" "Head this damn junk for the border." "Have a cigarette," I said. I wondered if he would head for the border and what I would do if he did, but he didn't. "The detail's all fucked-up," he said. "Where's the Lincoln? Where's the Macpap? The British? The Franco-Belge? Nobody's seen fuck-all of 'em. The bastards are driving to the sea," he said. "Maybe they've got to Tortosa already; we'll find out. If France don't come in now, we're fucked ducks. Mucho malo," he said. "Mucho fuckin malo."

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of Americans in Spain (1939), p. 133

- Every town along the Mediterranean shore was empty and deserted. The road was jam-packed with peasants evacuating toward the north, on mule-back, in donkey-carts, afoot. They looked at us in the cab of the truck, moving against the stream they made, and they kept moving. Hundreds were camped along the roads; hundreds were plodding north toward Barcelona, their few possessions, mattresses, blankets, household utensils, domestic stock, on their backs, in wheelbarrows or on their burros' backs. Little children were walking, holding onto their mother's skirts; women carried babies; older children were driving goats, sheep; old men were helping old women along the road; their faces were impassive, dark with the dust of the roads and fields, lined and worn. Their eyes alone were bright but there was no expression in their eyes. Looking at them you knew what they were thinking: 'Franco is coming; Franco is coming.'

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of Americans in Spain (1939), p. 134

- Then near-by Tarragona was bombed; the Spanish, British, and American nurses went about their work as the windowpanes rattled and the hideous drumming reverberated throughout the house. We all ran out onto the flagstone terrace to watch the black smoke rise over Terragona, and by morning of the next day the word had come that the Italian Fascist troops had reached the sea at Vinaroz, below Tortosa, cutting Loyalist Spain away from Catalonia, and all traffic had been cut between Barcelona and Valencia. (In Rome, the Pope gave is apostolic benediction to the sacred cause of General Franco.)

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of American in Spain (1939), p. 146

- We heard- a shithouse rumor?- that we dominated the heights surrounding Lerida and Balaguer (this was different); the newspapers reported that the offensive was gaining ground everywhere; the Non-Intervention Committee met again and issued another of its 'decisions.' This time it was decided once more to withdraw all foreign 'volunteers' from Spain, but England's perfidious hand could be seen as plain as day, for wasn't Mr. Chamberlain interested in concluding an agreement with Banjo-Eyes? And wasn't the 'withdrawal' contingent upon British and French concession of belligerent rights to Franco, which would tip the scales even farther in his favor by legalizing what already existed- the shipment of arms, munitions, planes and tanks and men into his territory?

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of American in Spain (1939), p. 170

- North's news of Europe was disheartening. Hitler had mobilized a million and a half men on the Czech and French borders, presumably for 'maneuvers'; probably for aggression against Czechoslovakia if the democracies, as they are euphemistically described, remained supine. Roosevelt and Hull had, it is true, made strong speeches against Fascist aggression within the week, and called for united democratic opposition, but when would the talking end and what good would it do? Franco, unlike the Spanish Loyalist Government, had given a categorical refusal to the Non-Intervention Committee's alleged plan for evacuation of foreign volunteers; he did worse, he said he would accept it in exchange for belligerent rights, immediately granted.

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of American in Spain (1939), p. 297

- "If you lose [a war," the great American novelist of the civil war, Ernest Hemingway, exclaimed in 1939, "you lose everything and your ideology won't save you." The Lincoln volunteers- whom Hemingway disparaged as the "ideology boys"- clung to the opposite view. Although they "lost the war," their last commander, Milton Wolff, insisted that "neither the Spaniards nor the [international volunteers], nor anti-fascists of any mettle, lost their ideology, much less 'everything.'" To Wolff, writing twenty years after Hemingway's suicide, it was precisely ideology that had "saved us. And may yet save the world." Indeed, it was this spirit of commitment- an unyielding optimism in the face of defeat- that distinguished the Lincoln veterans. For them, Spain lived not as the landscape for a novel or as a place of metaphysical inspiration. "Spain"- the word, the country, the cause- embodied ideology and political passion, anguish and hope; the ordeal of Spain became the essential continuity of their lives. Anticipating this half-century's commitment, the poet Genevieve Taggard composed "To the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade" in 1941:

Say of them,

They are no longer young, they never learned

The arts, the stealth of peace, this peace, the tricks of fear;

And what they knew, they know

And what they dared they dare.- Peter N. Carroll, The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1994), p. 4-5

- The battle for Madrid commenced on a gray, misty morning, November 7, 1936. As a cavalry column of Moorish mercenaries, bolstered by the rhythm of heavy drumbeats, rode toward the Toledo bridge, a hastily organized group of young men and women fired from behind rough barricades at the advancing troops. Their antique pistols and hunting rifles scarcely interrupted the charge. But suddenly, a motorcyclist appeared with a machine gun and sent the horsemen into retreat. Italian tanks then forged ahead of Franco's professional legionnaires and mercenaries; and, after the fog had lifted, German Junkers rained bombs through the cloudy skies. Again and again, the unpracticed Republican militia, emboldened by individual heroics, met the attack valiantly, using small arms against the troops and sticks of dynamite against the tanks. The fascists made small progress that day. At dawn of the next day, as Madrid girded for a second ground assault, the city's frantic residents witnessed a remarkable parade down the broad Gran Via: a neat procession of nearly 2,000 soldiers, dressed in corduroy uniforms and steel helmets. Assuming the men were Soviet allies, the Madrilenos raised their fists in the Popular Front salute and shouted, "Long live the Russians!" Their error was understandable. Few citizens of Spain knew of the existence of the newly formed International Brigades, a contingent of foreign volunteers who had come to Spain to defend the Republic. These recruits had left their homes in Great Britain and France, Yugoslavia and Poland, Belgium and Austria; many were political refugees from fascist Italy and Germany. Despite scant military training, they exuded enthusiasm. And under the leadership of Soviet general Emil Kleber, a Hungarian Jew trained in the Soviet Union, they brought much more than a military presence to the Republican cause. These Internationals- ultimately they would number 40,000 troops from 52 countries- symbolized a political camaraderie that linked the Spanish civil war to the titanic ideological conflicts of the 1930's: the struggles of fascism, communism, and democracy. In the days and weeks and months that followed, these volunteers would join the Spanish militia to face the fascist tide.

- Peter N. Carroll, The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1994), p. 11-12

- News of the creation of the International Brigades raced through the Communist grapevines around the globe: the very existence of a multinational army promised to fulfill the Marxist prophesy that one day the "workers of the world" would unite against their common oppressors. In every country, such optimism encouraged the enlistment of volunteers eager to fight in Spain. When the American Communist party spread the word about recruitment through a network of district organizers, the response was immediate. From the waterfront docks and the fur trades, from union halls and ethnic associations, from bread lines and Communist party cells, dozens of men came forward within weeks to join the fight for Republican Spain. Viewing themselves as part of an international proletariat, American radicals welcomed this opportunity to take the struggle against fascism to another stage of history: it was possible now, in Spain at least, to fight back with arms.

- Peter N. Carroll, The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1994), p. 12

- As word of recruitment for the International Brigades began to filter through the American Communist network in the autumn of 1936, large numbers of volunteers came forward to enlist. The party's organizing committee soon realized that its responsibility had shifted. Instead of having to locate a few trusted volunteers to send to Spain, they now had to worry about screening any undesirable elements from the diverse recruits who were offering their services. In this unique military crusade, symbolic of the unity of the international working classes, party leaders wanted to exclude mere adventurers who lacked a political understanding of the anti-fascist struggle. They also feared that government or enemy spies might attempt to subvert the project. The party insisted on secrecy, therefore, not because Communists harbored a devious conspiracy to overthrow a government- after all, they always boasted of their initiatives on behalf of the Spanish Republic- but because party members did not wish to be caught violating American recruitment laws. In any event, the leadership decided that each volunteer would have to be interviewed personally by a special committee.

- Peter N. Carroll, The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1994), p. 64

- The Spanish Civil War and the fight against it did, in part, alert the world to the nature of fascism. The story of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade is generally known. It was a contingent of committed Black and White Americans, three thousand in number, who went to fight against fascism. Had the circumstances been different, some of the Black Americans would have been willing to fight in the Italian-Ethiopian War. Ethiopia was overrun in a matter of months, and there was no organized effort to get Black Americans to fight in this war. Those who were willing to go were left with their frustrations. To some of them fighting with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the war against fascism in Spain was an alternative.

- John Henrik Clarke, Foreword to Mississippi to Madrid: Memoir of a Black American in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1989), p. xi

- The events in which we had participated at home had had a direct influence on our decision to go to Spain. We were trade unionists. We had worked with the unemployed and the poor. In many ways, we viewed the Spanish struggle as an extension of our fight against reaction at home. Most significantly, we wanted to focus the nation's attention on the growing threat of fascism, and the danger it posed to international peace. We were later to be called "premature anti-fascists," and we accepted this title proudly, though it was not meant as a compliment by the State Department spokesman who first coined the term. After all, we had bucked the system- the U.S. government, even under Franklin Delano Roosevelt, had remained neutral in the various worldwide struggles against fascism, right up until the time World War II began. But in 1937 many people around the world did recognize the threat fascism brought to world peace, and it was our fervent hope that by aborting the fascist takeover in Spain, we might prevent a second world war.

- Harry Fisher, Comrades: Tales of a Brigadista in the Spanish Civil War (1998), p. xx

- We weren't going to win the war, that was clear by now. But there had been a purpose to our fight, and that was what had given us our strength. Otherwise, the war would have been an unending horror, a tragic waste of precious life. But Spain's struggle was a different kind of war- a people's fight for its democratic rights. I felt proud to have been part of the International volunteer army that had come to Spain to put an end to fascism.

- Harry Fisher, Comrades: Tales of a Brigadista in the Spanish Civil War (1998), p. 158

- They gave up everything, their homes, their country, home and fortune- fathers, mothers, wives, brothers, sisters and children, and they came and told us: "We are here, your cause, Spain's cause, is ours. It is the cause of all advanced and progressive mankind." Today they are going away. Many of them thousands of them, are staying here with the Spanish earth for their shroud, and all Spaniards remember them with the deepest feeling.

- Isidora Dolores Ibárruri Gómez, popularly known as "La Pasionara", in a speech in Barcelona on 15 November 1938, as quoted by Hugh Thomas in The Spanish Civil War (1961), p. 558

- Comrades of the International Brigades! Political reasons, reasons of State, the welfare of that same cause for which you offered your blood with boundless generosity, are sending you back, some of you to your own countries and others to forced exile. You can go proudly. You are history. You are legend. You are the heroic example of democracy's solidarity and universality. We shall not forget you, and when the olive tree of peace puts forth its leaves again, mingled with the laurels of the Spanish Republic's victory- come back!

- Isidora Dolores Ibárruri Gómez, in a speech in Barcelona on 15 November 1938, as quoted by Hugh Thomas in The Spanish Civil War (1961), p. 558

- When the smouldering powder keg of south-west Europe finally exploded into life in July, 1936, and civil war broke out in Spain, a number of far more powerful and certainly much wealthier nations grasped at the unexpected opportunity to try out their latest military aircraft and other equipment under operational conditions, in the belief that invaluable battle experience with modern weapons would thus be gained. Had the Spanish people been left to fight out their quarrel among themselves much unnecessary bloodshed and distress would probably have been saved, with part of the small Spanish Air Force flying with the Government forces and part with the Revolutionary forces, but unfortunately both sides soon began to receive aid from foreign countries. The Communist Government armies were sent quantities of I-15 and I-16 fighters and some SB-2 bombers from Russia, as well as a continuous flow of new aircraft from France. However, following the example of Mussolini, Adolf Hitler decided to give active assistance to General Francisco Franco Bahamonde, the principle leader of the insurgents, and thousands of men and hundreds of tons of supplies were sent to Spain in the course of the next three years, including the Luftwaffe "Volunteer" Corps identified officially by its unit number of "88" and popularly known as the Legion Kondor.

- John Killen, A History of the Luftwaffe (1968), p. 67

- The Spanish Civil War, which had afforded such a fortuitous opportunity for the Luftwaffe to try out its strength under actual battle conditions, served just as useful a purpose for the Soviet Air Force, and soon awakened the Red aircraft industry to the plain fact that it was falling badly behind the times. The standard Russian fighters sent to Spain, mainly I-15 and I-153 biplanes and I-16 monoplanes, held their own against the Heinkel He 51s initially supplied to the Legion Kondor, but proved to be outclassed in every way by the Messerschmitt Bf 109s later sent against them. The Russian SB-2 aircraft, the so-called "fast bombers" needing no fighter escort, turned out to have all the disadvantages of the Dornier Do 17s in the same class with none of the advantages of the German machines, and for reconnaissance the Russians could provide nothing better than the archaic R-5 biplanes. No dive-bombing ground support aircraft comparable to the German Henschel Hs 123 or Junkers 87 were available. By 1939, the Russian aircraft designers were showing the world that the lessons of the Spanish Civil War had been heeded. Lavochkin was introducing the first of his highly-successful LA series of single-seater fighters, soon to be followed by the even more famous LAGG series; Petlyakov's twin-engine PE-2 was about to enter service, and subsequently become one of the outstanding medium bombers of the Second World War; and Ilyushin had just designed the Il-2 Sturmovik ground-support aircraft later to prove unequalled in its class anywhere in the world.

- John Killen, A History of the Luftwaffe (1968), p. 178

- The Madrid victory parade took place on May 19. This time we formed the letters "F-R-A-N-C-O," a still more difficult flying maneuver. We flew straight up the Castellana, high in the clear sky, while thousands of troops, tanks, and guns moved through the city. The enthusiasm was unsurpassed. A few months later I retired from the air force, but I remain in the reserve to this day. On October 19, 1939, Paz and I were married in Seville's magnificent cathedral. We now have six children, two girls and four boys, age eight to twenty-four. We had won the war, yet our troubles were not over by any means. A major work of reconstruction lay ahead for a ruined but vigorous and proud country. But a new World War was looming up menacingly and was to delay and hinder the steep uphill climb; also ahead lay the years of isolation by a hostile world. The years have flown and hate's sharp and bitter edge has been dulled and blunted by the healing balm of time. New generations have sprung up to fill the ranks where once stood veterans, united, shoulder to shoulder, to save Spain, our beloved country, from national death. Reconstruction has, in truth, flourished under the warm sun of social justice and twenty-five years of peace, our hard-won peace. The firm and steady hand of a great captain and patriot, in my view one of the greatest in Spain's long history, has held the tiller of the ship of state through fierce gales and in and out of sharp reefs, to steer it to a calm and prosperous anchorage. If the spirit, courage, and overwhelming national enthusiasm born on July 18, 1936, can be kept alive by present generations and kindled in succeeding ones Spain need have no fear from any internal foes nor from inveterate enemies beyond her frontiers.

- José Larios, Combat Over Spain (1966), p. 266-267

- I find it difficult to define my feelings when peace came at last. The immediate reaction was one of great joy, tremendous feeling of relief. I had survived the long-drawn-out struggle unscathed and was back again once more with the people I most loved, Paz and my family. I could not quite believe it. It seemed too good to be true, and I expected to wake up any morning and find myself back at the front on operations. Soon the anticlimax set in. I suddenly felt very tired; the prolonged physical and spiritual effort left me momentarily exhausted. I felt much older and, probably, wiser. I looked forward to a happy married life. But the future again loomed up uncertain, black, and foreboding; sparks were flying and Europe was about to burst into flames at any moment. And who could tell if we were to be forced into the conflict? No one at the time could predict. We were to suffer long years of uncertainty during the World War while Spain slowly but proudly recovered from her deep wounds, unaided and isolated. Our not being drawn into war (which would have completed Spain's ruin), was, as everyone knows now, entirely due to General Franco's inflexible firmness of purpose. Not even Hitler, at the height of his power, was able to sway him to his side or alter his determination to keep Spain out of it- a remarkable feat. From the conclusion of the Spanish Civil War to this day, much has happened and much good has come to this country. Her astounding and heroic effort has not gone unrewarded, as fifteen million tourists (in 1964) can testify.

- José Larios, Combat Over Spain (1966), p. 268-269

- From America, Marion watched the Spanish Republic fall, Franco seize total power, Hitler wage war against freedom throughout Europe, and, ultimately, America, England, France, and Russia fight as allies against Germany and Italy. She recollected sadly her admonition to the Rotary Club of Reno that Americans everywhere must take a stand against fascism in Spain or watch their sons die later in Germany. Marion noted the irony that America, France, and England finally did exactly what she and Bob Merriman and the Abraham Lincoln Battalion had done voluntarily- join internationally in a commitment to defeat fascism.

- Warren Lerude, in American Commander in Spain: Robert Hale Merriman and the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1986) by Marion Merriman and Warren Lerude, p. 235

- The men of the Lincoln Brigade, the "premature antifascists," those who were physically able, volunteered early in our armed forces, gave their blood and their lives. On the roster of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade there are the names of 331 men who survived Spain to serve honorably in the U.S. Army or American medical services. This does not include those veterans who served in the Merchant Marine, many of whom were killed when their ships were attacked. These are the men and women I salute, my "compadres," my dearest friends throughout these long years. Now, at the end of 1985, like Janus I can look back at the lessons of the past, to the heroes- and forward to a better world. There will always be fighters for freedom, men and women of the highest moral resolve.

- Marion Merriman, in American Commander in Spain: Robert Hale Merriman and the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1986) by Marion Merriman and Warren Lerude, p. xiii

- Último aviso: he decidido terminar rápidamente la guerra en el Norte de España. Quienes no sean autores de asesinatos y depongan las armas o se entreguen serán respetados en vidas y haciendas. Si vuestra sumisión no es inmediata arrasaré Vizcaya empezando por las industrias de guerra. Tengo medios sobrados para ello.

- Last warning: I have decided to end the war in the North of Spain quickly. Those who have not committed murders and who lay down their arms or turn themselves in will see their lives and property respected. If your submission is not immediate, I will wipe out Vizcaya, beginning with the industries of war. I have more than enough means to do it.

- General Emilio Mola [citation needed]

- Guernica fue Punto Hoy no es más que brasa cenizas Punto En este momento arde todavía pueblo tres horas bombardeo intensísimo bombas incendiarias lo han destrozado totalmente Punto Aldasoro, Torre, yo llegamos allí espantados Punto Diez mil mujeres niños huyen carreteras temiendo ser ametrallados por aviación mañana al amanecer como lo fueron esta tarde Punto Ante esta catástrofe con amenaza hecha hoy mismo destrozar incendiar Bilbao esta semana sólo suplicamos háganse cargo situación angustiosa

- Guernica was Stop Today it is no more than embers ashes Stop In this moment town still burning three hours intense bombardment incendiary bombs have totally destroyed it Stop Aldasoro, Torre, I arrived there horrified Stop Ten thousand women children fleeing highways fearing being machine-gunned by aircraft tomorrow at dawn as they were this afternoon Stop Before this catastrophe with threat made just today to destroy burn Bilbao this week we entreat only take charge dreadful situation

- Telesforo Monzón, telegram to the President of the Council of Ministers, 27 April 1937 [citation needed]

- When one thinks of the cruelty, squalor, and futility of war - and in this particular case of the intrigues, the persecutions, the lies and the misunderstandings - there is always the temptation to say: "One side is as bad as the other. I am neutral." In practice, however, one cannot be neutral, and there is hardly such a thing as a war in which it makes no difference who wins. Nearly always one side stands more or less for progress, the other more or less for reaction. The hatred which the Spanish Republic excited in millionaires, dukes, cardinals, play-boys, blimps, and what-not would in itself be enough to show one how the land lay. In essence it was a class war. If it had been won, the cause of the common people everywhere would have been strengthened. It was lost, and the dividend-drawers all over the world rubbed their hands. That was the real issue; all else was froth on its surface.

- George Orwell, "Looking on the Spanish War" (1942)

- The outcome of the Spanish war was settled in London, Paris, Rome, Berlin - at any rate, not in Spain.

- George Orwell, "Looking on the Spanish War" (1942)

- Ante Dios y ante la Historia que a todos nos ha de juzgar, afirmo que durante tres horas y media los aviones alemanes bombardearon con saña desconocida la población civil indefensa de la histórica villa de Gernika reduciéndola a cenizas, persiguiendo con el fuego de ametralladora a mujeres y niños, que han perecido en gran número huyendo los demás alocados por el terror.

- Before God and before History which must judge us all, I affirm that for three and one-half hours, German planes bombarded with unheard-of fury the defenceless civilian population of the historic city of Gernika, reducing it to ashes, chasing with machine-gun fire women and children who perished in great number, fleeing the stampede of others driven mad by panic.

- José Antonio Aguirre, lehendakari of the Basque Country [citation needed]

- Aguirre miente. Nosotros hemos respetado Guernica, como respetamos todo lo español.

- Aguirre is lying. We have respected Guernica, as we respect everything Spanish.

- Francisco Franco [citation needed]

- The internationalization of the civil war through foreign aid, diplomacy and troops is indisputable, as is the fact that decisions made by foreign powers played an important role in the war's evolution. The two most important decisions affecting aid to the Republic were the Non-Intervention in Spain Agreement, signed by 27 European nations at the end of August 1936, and the Soviet decision in mid-September to assist the Republic. From the beginning of the war Britain declared neutrality and convinced the Popular Front French government to reverse its initial decision to aid its Spanish compatriots. France then suggested the non-intervention pact to prevent fascist support of the Nationalists. However, Germany and Italy, and to a lesser extent Portugal, continued to arm the Nationalists, while all the major democracies, including the United States, followed the pretense of non-intervention. The democracies' decision to abandon the Republic was a result of both domestic concerns and geo-strategic interests. Although their populations were deeply divided, none of the liberal democratic governments were comfortable with the Spanish left-leaning democracy of July 1936. They were even less so once news of the initial revolutionary experimentation and anti-clerical violence was reported, often by conservative Spanish diplomats in their countries who overwhelmingly defected to the rebel cause. Even so, the Nationalists' claim that they fought to save Spain from Bolshevism and for Christian civilization was much more compelling than anti-fascism in the mid-1930s. Thus, even after the Republican state could demonstrate that social revolution and anti-clerical violence had been contained, the democratic powers were more invested in appeasing Nazi Germany than in fighting fascism, a strategy that culminated in the Munich conference of September 1938.

- Pamela Beth Radcliff, Modern Spain: 1808 to the Present (2017), p. 196-197

- The military impact of foreign aid on the war's outcome continues to be debated, but the Republican cause was significantly undermined by both the low quality of material and the irregular timing of its arrival. The Republic was not poor, since it controlled the gold reserves, about a quarter of which were set to Paris early on and the rest to Moscow to pay for Soviet supplies. But most of the Soviet weapons and materiel were no match for the Nazi armaments that Hitler wanted to test before unleashing his own military ambitions. Because of the non-intervention pact, most of the rest of the materiel for the Republican side had to be purchased at high prices from private buyers. Finally, in terms of timing, the Republic was virtually starved of weapons at crucial points: during the summer of 1936 before the start of Soviet aid and from the end of 1938. Of the 66 shipments from the USSR, 52 arrived between October 1936 and the end of 1937. And, in contrast to more than 100,000 troops sent by Germany and Italy, the USSR sent only 2,000 advisers, in addition to the 31,000-32,000 volunteers of the International Brigades that were organized by the Communist International. The International Brigades have been attacked as Stalinist stooges and celebrated as heroic anti-fascists, with additional debates about their impact on the outcome of the war itself. Undoubtedly reflecting a variety of motives, the volunteers from over 50 countries probably played a positive role in several Republican battles, including the defense of Madrid, but overall, foreign troops contributed more to the Nationalist victory, especially if the Moroccan troops are included. In any case, the Brigades were sent home in September 1938, in hopes that the Nationalists would do the same with their larger contingent of foreign fighters. Instead, the departure of the Brigades marked the beginning of a precipitous slide toward final defeat.

- Pamela Beth Radcliff, Modern Spain: 1808 to the Present (2017), p. 197

- In addition to the Nationalists' effective internal unification, the foreign aid they received was certainly also a factor in their victory. Without foreign aid a rebel force with no access to government institutions or gold reserves would have had no chance of success. Although the Nationalist war effort was largely financed by loans, both sides spent about the same. However, the apparent parity of resources obscures the superiority of Germany and Italy's consistent and high-quality support of the Nationalist side, especially n the summer of 1936 and from mid-1937 until the end of the war, as the gap in aid continued to grow. From the use of German planes to airlift the Army of Africa to the mainland in July 1936, to the arrival of the Condor Legion air force in October of that year, followed by Italian troops in December, the fascist powers maintained their logistical aid until the end. The Condor Legion carried out perhaps the most notorious action of the war, the aerial bombing of the civilian population of Guernica on April 26, 1937, which killed at least 1,500 and came to symbolize the horrors of "total" war in Picasso's famous painting. The number of foreign fighters was definitely higher on the Nationalist side, including 19,000 Germans and over 78,000 Italians, in addition to the 70,000 native Moroccan Regulares. While foreign aid was superior, there is also evidence that the Nationalists utilized that aid more effectively than their enemies, thus securing their rearguard and keeping their army loyal.

- Pamela Beth Radcliff, Modern Spain: 1808 to the Present (2017), p. 203

- The Republican defeat in the Civil War was followed by nearly forty years of dictatorship that ended only with the death of the man whose name came to define the regime. While the Franco regime began and ended as a dictatorship, its adaptive survival over four decades has generated ongoing debates about its identity. Was it a fascist regime, a military dictatorship, a traditional authoritarian regime, or some hybrid type? The regime began as a de facto ally of the fascist powers during the Second World War and ended as an ally of the democratic "West" in the Cold War. Evolving along with its international alliances was the regime's economic and cultural policies, which began with an isolationist autarky designed both to promote national self-sufficiency and to keep out impure foreign ideas, and ended with a booming tourist industry and economic integration into cultural pluralism. And, while the political institutions of the regime never underwent a parallel evolution, there was a shift in leadership away from fascist ideologues and toward more "technocratic" modernizers, whose primary goal was to increase at least passive support for the regime through higher standards of living rather than indoctrination and mass terror.

- Pamela Beth Radcliff, Modern Spain: 1808 to the Present (2017), p. 209

- In my evaluation, the role of the Communist party wasn't much of a factor. The party was just there, doing its job, and, as far as I could see, doing a good job. The squabbles about leadership, how the various high-level political commissars had done their jobs in Spain hadn't really touched me. I had heard of the arguments, especially about individual commissars on top, but there wasn't any direct connection with my life or work. The party's key role in the International Brigades somehow didn't make itself felt overtly, not, at least, in the medical service, certainly not at my level. I had joined the Spanish party somewhere along the line, but I don't remember attending any meetings. It was just something American party members and YCLers did. My membership card had a picture of me wearing my heavy, knitted, gray wool scarf, the one that so often had lice. But as I was assessing what had happened, the role of party was not a very important part of my thinking. It was just a given in my thoughts, a necessary part of the struggle against fascism.

- Hank Rubin, Spain's Cause Was Mine: A Memoir of an American Medic in the Spanish Civil War (1997), p. 146

- To what purpose had so many given their lives, had I offered mine? The war in Spain was nearly lost. In fact, in the short space of three and a half months, it would end. Under the circumstances, it was hard to believe that my comrades had not died in vain. Yet I also knew that the battle in Spain had been necessary and worthwhile, that the struggle for decency in the world would and must continue. If we had not defeated fascism, we had at least demonstrated a will to resist. I knew, too, that after taking a short time to draw a fresh breath, I would be a part of that movement, even if I could not conceive of what form my contribution might take. So why did I volunteer, why did I go? There is no easy answer. But one thing is clear. I have never regretted my decision. Quite the contrary! To support what I believed in, to combat forces that stood for everything I considered evil, to have put myself at risk for something other than myself, was, and is, a source of great personal pride. That it was an instantaneous decision was consonant with many of the major decisions later in my life- buying homes, making investments, deciding to get married- all rarely burdened by the regret of hindsight. I knew that the civilian life I would return to would not be serene, but I was committed to a struggle for a better world. "Antifascist" and "prodemocracy" had become the words that I felt defined me. If I left one battlefield, I would find another one on which to fight for a better world. In a real sense, for me the fight in Spain had been more than a fight to save only Spain. I came to see it, as much as anything, as a fight against fascism and a struggle for greater democracy in our own country.

- Hank Rubin, Spain's Cause Was Mine: A Memoir of an American Medic in the Spanish Civil War (1997), p. 146-147

- We were pariahs to our government. When Brigaders volunteered for the armed forces in World War II, the official army line, at first, was that we were not to be sent outside of the continental limits, so that we would not have contact with European communists. This ruling was later successfully challenged. Even so, most of us were sent to the Pacific combat zone. But despite all of the government's fears about our politics, some of the Brigaders, because of their experience and skills, were needed for the war effort. Some, therefore, were sent across the Atlantic to assignments behind the German and Italian lines to work with the various resistance forces, which, ironically, were often communist or communist-led. More than six hundred American vets served in World War II, in addition to another three hundred more in the merchant marine. In all, about twenty-five Spanish vets gave their lives for their country in World War II. Many were decorated for bravery. Between sixty and seventy, including myself, were commissioned as officers. As a side note, many Spaniards-in-exile volunteered to fight with the French, and when the tanks of the Free French entered Paris for its liberation from the Germans, many were manned by Spanish personnel, and three tank turrets carried the names of Spanish battles- Madrid, Teruel, or Jarama- painted on their sides.

- Hank Rubin, Spain's Cause Was Mine: A Memoir of an American Medic in the Spanish Civil War (1997), p. 152-153

- A Nationalist victory in the Civil War in Spain would mean that France would be surrounded on three sides by potentially hostile countries. This would make it easier for Germany to attack Russia without being afraid of French attacks in her rear. For this torturous reason, the Soviet Government had a strong interest in the prevention of a Nationalist victory. The Spanish War also afforded the Communist Party, with its discipline, its skill at propaganda, and its prestige deriving from its connection with Russia, a great chance to secure in Spain the establishment of the second Communist State. But such a Communist victory wold have alarmed Britain and France, the two powers to whom, for diplomatic reasons, Russia wished to draw closer. It might even make a general war more likely. It might waste Russian war material. For these reasons, Stalin probably did not send orders to the Spanish Communist party, and his chief agents there, Cordovilla and Stepanov, to make full use of the opportunity to gain control of the Spanish Republic. Nor did he send arms to Spain.

- Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War (1961), p. 215

- The Spanish Civil War exceeded in ferocity most wars between nations. Yet the losses were less than had been generally feared. The total number of deaths caused by the war appears to have been approximately 600,000. Of these about 100,000 may be supposed to have died by murder or summary execution. Perhaps as many as 220,000 died of disease or malnutrition directly attributable to the war. About 320,000 probably died in action. The cost of the war, including both internal and external expenditures, was named later by the Nationalists at 30,000 million pesetas (£3,000 million in 1938 money). The chief cost was in labour, due on the one hand to the deaths and permanent disabilities caused, and on the other to the exile of 340,000 persons at the end of the war. Nationalist authorities estimated that approximately 4,250 million pesetas' worth of damage had been done to real property during the course of the war. Since this was supposed to be damage caused only by the Republicans, it is probably an under-estimation. 150 churches were totally destroyed and 4,850 damaged, of which 1,850 were more than half destroyed. 183 towns were so badly damaged that General Franco 'adopted' them- his Government, that is, undertook to pay the cost of restoration. This probably does not take into account another 250,000 which were partially damaged.

- Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War (1961), p. 606

- In July of 1936 General Francisco Franco led a revolt against the democratically elected government of Spain. Under his command was a well-trained army of mercenaries from Morocco. Italy's Benito Mussolini kept his pledge to Franco by sending one hundred thousand soldiers directly to Spain from the war in Ethiopia. From Germany Adolph Hitler sent artillery, technicians, a large air force and twenty-five thousand tanks. Meanwhile, the Portuguese government dispatched two divisions of soldiers to aid Franco. These events in Spain stunned and shocked the conscience of people throughout Europe and the world. The government of Spain, in its effort to withstand the attack of the fascist armies, appealed to the democratic governments of the world for their support. Instead of sending help, the governments of England, France and the United States placed an embargo on arms to Spain. Nevertheless, freedom-loving people from around the world answered Spain's call for help. Within a few months thousands of men and women from many countries flocked to Spain with the hope of stopping fascism. An estimated forty thousand volunteers served in the International Brigades. Of the three thousand from the United States, almost one hundred were Black. The number of people who fought in the International Brigades was only a small speck when measured against the thousands of Spaniards who fought in the Republican army. However, the role played by the internationals was very significant in preventing Franco from achieving the quick victory that he expected when his forces attacked Madrid. Madrid held out for three long years. The war ended in Spain by March, 1939. Poland was invaded by Hitler's Nazi army the following September, thus signalling the start of World War II.

- James Yates, Mississippi to Madrid: Memoir of a Black American in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1989), p. xiii-xiv

- I was just beginning to learn about the reality of Spain and Europe, but I knew what was at stake. There the poor, the peasants, the workers and the unions, the socialists and the communists, together had won an election against the big landowners, the monarchy and the right-wingers in the military. It was the kind of victory that would have brought Black people to the top levels of government if such an election had been won in the USA. A Black man would be Governor of Mississippi. The new government in Spain was dividing its wealth with the peasants. Unions were organizing in each factory and social services were being introduced. Spain was the perfect example for the world I dreamed of. Now all of it was about to be wiped out. The former rulers were determined to retake power. They were being supported by fascists all over the world, including, I was sure, many in the United States. How could I not volunteer?

- James Yates, Mississippi to Madrid: Memoir of a Black American in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1989), p. 96

- The capitalist newspapers painted the war as if we were losing. Several times they had eagerly reported that Madrid had fallen to Generalissimo Franco and Mussolini's troops, when it hadn't. They were aware that a quick fascist victory would obscure the one-sided nature of the embargo. While men, war materials and even medical supplies were being denied the Republicans, French and English capitalists were not only lending the fascists moral support, but supplying them with guns, planes and tanks. The fascists, including Hitler's Germany, received oil from the United States, and in particular from the large oil companies. Without that support they could not maintain their huge war machines. I didn't believe the newspapers. I knew from the experience of our march to Springfield just how falsely events were reported. Madrid would not fall. Republican Spain would not fall. We would go on to create other Republican states throughout the world. Perhaps even in Mississippi!

- James Yates, Mississippi to Madrid: Memoir of a Black American in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1989), p. 110

- Albacete by early 1937 had become a United Nations of a special kind. Men and women of all different tongues and nationalities, young and old, all came together to fight side by side with the Spanish people. The Spaniards were not only fighting to save themselves and their country from fascism but Europe and the whole world from plunging into the horror of war.

- James Yates, Mississippi to Madrid: Memoir of a Black American in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (1989), p. 123

External links

This article is issued from

Wikiquote.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.