.jpg)

Few men are willing to brave the disapproval of their fellows, the censure of their colleagues, the wrath of their society. Moral courage is a rarer commodity than bravery in battle or great intelligence. Yet it is the one essential, vital quality for those who seek to change a world that yields most painfully to change.

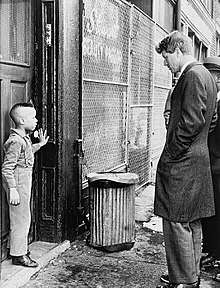

Robert Francis Kennedy (20 November 1925 – 6 June 1968), often referred to by his initials RFK, was an American politician and lawyer. Kennedy was the U.S. Attorney General (1961–1964) and a Senator (1965–1968); he was the brother of President John F. Kennedy and Senator Edward "Ted" Kennedy

Quotes

The United States Government has taken steps to make sure that the constitution of the United States applies to all individuals.

A revolution is coming — a revolution which will be peaceful if we are wise enough; compassionate if we care enough; successful if we are fortunate enough — But a revolution which is coming whether we will it or not. We can affect its character; we cannot alter its inevitability.

- The Irish were not wanted there [when his grandfather came to Boston]. Now an Irish Catholic is president of the United States … There is no question about it. In the next 40 years a Negro can achieve the same position that my brother has. … We have tried to make progress and we are making progress … we are not going to accept the status quo. … The United States Government has taken steps to make sure that the constitution of the United States applies to all individuals.

- AP report with lead summarizing of remarks stating "Robert F. Kennedy said yesterday that the United States — despite Alabama violence — is moving so fast in race relations a Negro could be President in 40 years." "Negro President in 40 Years?" in Montreal Gazette (27 May 1961)

- I thought they'd get one of us, but Jack, after all he'd been through, never worried about it.... I thought it would be me.

- After hearing that his brother John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas, TX, on 22 November 1963, as reported by Ed Guthman in Peter Collier & David Horowitz's The Kennedys: An American Drama (1984), ISBN 1893554317, p. 249

- To say that the future will be different from the present is, to scientists, hopelessly self-evident. I observe regretfully that in politics, however, it can be heresy. It can be denounced as radicalism, or branded as subversion. There are people in every time and every land who want to stop history in its tracks. They fear the future, mistrust the present, and invoke the security of a comfortable past which, in fact, never existed. It hardly seems necessary to point out in California - of all States -- that change, although it involves risks, is the law of life.

- The Opening to the Future (1964)

- One-fifth of the people are against everything all the time.

- Address at the University of Pennsylvania (6 May 1964), quoted in [http://www.thisdayinquotes.com/2011/05/about-one-fifth-of-people-are-against.html The Philadelphia Inquirer (7 May 1964)

- The problem of power is how to achieve its responsible use rather than its irresponsible and indulgent use — of how to get men of power to live for the public rather than off the public.

- "I Remember, I Believe," The Pursuit of Justice (1964)

- In the words of the old saying, every society gets the kind of criminal it deserves. What is equally true is that every community gets the kind of law enforcement it insists on.

- The Pursuit of Justice pt. 3, "Eradicating Free Enterprise in Organized Crime," (1964)

- Alexander Lacassange Attribution of original quote

- What is objectionable, what is dangerous about extremists is not that they are extreme, but that they are intolerant. The evil is not what they say about their cause, but what they say about their opponents.

- "Extremism, Left and Right," The Pursuit of Justice, pt. 3 (1964)

- Ultimately, America's answer to the intolerant man is diversity, the very diversity which our heritage of religious freedom has inspired.

- "Extremism, Left and Right," pt. 3, (1964)

- The free way of life proposes ends, but it does not prescribe means.

- "Berlin East and West," The Pursuit of Justice, pt. 5, (1964), p. 108

- Just because we cannot see clearly the end of the road, that is no reason for not setting out on the essential journey. On the contrary, great change dominates the world, and unless we move with change we will become its victims.

- Farewell statement, Warsaw, Poland, reported in The New York Times (2 July 1964)

- When there were periods of crisis, you stood beside him. When there were periods of happiness, you laughed with him. And when there were periods of sorrow, you comforted him.

- Tribute to John F. Kennedy, 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City (27 August 1964)

- Now I can go back to being ruthless again.

- Remark on his reputation for "ruthlessness" after winning his race for a seat in the United States Senate, quoted in Esquire (April 1965)

- About one-fifth of the people are against everything all the time.

- Speech at the University of Pennsylvania (6 May 1964)

- A revolution is coming — a revolution which will be peaceful if we are wise enough; compassionate if we care enough; successful if we are fortunate enough — But a revolution which is coming whether we will it or not. We can affect its character; we cannot alter its inevitability.

- Speech in the United States Senate (9 May 1966)

- Few will have the greatness to bend history itself; but each of us can work to change a small portion of events, and in the total of all those acts will be written the history of this generation.

- Day of Affirmation, address delivered at the University of Cape Town, South Africa (June 6, 1966); reported in the Congressional Record (June 6, 1966), vol. 112, p. 12430

- In my judgment, the slogan "black power" and what has been associated with it has set the civil rights movement back considerably in the United States over the period of the last several months.

- Remark during testimony of Floyd McKissick before a Senate subcommittee of which Kennedy was a member (December 8, 1966); reported in Federal Role in Urban Affairs, hearings before the Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization of the Committee on Government Operations, United States Senate, 89th Congress, 2d session, part 11, p. 2312 (1967)

- I expect one of the prices we pay for democracy is there are going to be differences. We pay a price but we get something very important in return.

- Speaking on his support for President Johnson in the upcoming presidential election (17 March 1967), as quoted in "I'll Campaign For Johnson," Says Kennedy"

- He has borne the burdens few other men have borne in the history of the world, without hope or desire or thought to escape them. He has sought consensus but he has never shrunk from controversy. He has gained huge popularity but he has never failed to spend it in the pursuit of his beliefs or in the interest of his country.

- On LBJ (June 3, 1967); quoted in "The World Turned Upside Down"

- Tragedy is a tool for the living to gain wisdom, not a guide by which to live.

- "Conflict in Vietnam and at Home" speech at Kansas State University on March 18, 1968 as part of the Alfred M. Landon Lectures on Public Issues.

- Gross National Product counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl. It counts napalm and counts nuclear warheads and armored cars for the police to fight the riots in our cities. It counts Whitman's rifle and Speck's knife, and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children. Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.

- Speech at the University of Kansas at Lawrence (18 March 1968)

- Every dictatorship has ultimately strangled in the web of repression it wove for its people, making mistakes that could not be corrected because criticism was prohibited.

- "Value of Dissent" speech Nashville, Tennessee (21 March 1968)

- He has called on the best that was in us. There was no such thing as half-trying. Whether it was running a race or catching a football, competing in school—we were to try. And we were to try harder than anyone else. We might not be the best, and none of us were, but we were to make the effort to be the best. "After you have done the best you can", he used to say, "the hell with it".

- Tribute to his father, Joseph P. Kennedy, read at Joseph Kennedy's funeral by Senator Ted Kennedy, November 20, 1969. Reported in Congressional Record (25 November 1969), vol. 115, p. 35877

- Something about the fact that I made some contribution to either my country, or those who were less well off. I think back to what Camus wrote about the fact that perhaps this world is a world in which children suffer, but we can lessen the number of suffering children, and if you do not do this, then who will do this? I'd like to feel that I'd done something to lessen that suffering.

- In an interview shortly before he was killed, responding to a question by David Frost about how his obituary should read.

- Are we like the God of the Old Testament, that we in Washington can decide which cities, towns, and hamlets in Vietnam will be destroyed? Do we have to accept that? I don't think we do. I think we can do something about it.

- About the Vietnam War, in his last speech at the Senate on the subject

- I called him because it made me so damned angry to think of that bastard sentencing a citizen for four months of hard labor for a minor traffic offense and screwing up my brother's campaign and making our country look ridiculous before the world.

- On calling Judge Oscar Mitchell for sentencing Martin Luther King, Jr., as quoted in Robert Kennedy: Brother Protector (2000), p. 173

Day of Affirmation Address (1966)

- Speech in Cape Town, South Africa (6 June 1966); with slight variants as quoted in Ripples of Hope : Great American Civil Rights Speeches (2003), edited by Josh Gottheimer

It is from numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped. Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

"Give me a place to stand," said Archimedes, "and I will move the world." These men moved the world, and so can we all.

- This is a Day of Affirmation, a celebration of liberty. We stand here in the name of freedom.

At the heart of that Western freedom and democracy is the belief that the individual man, the child of God, is the touchstone of value, and all society, groups, the state, exist for his benefit. Therefore the enlargement of liberty for individual human beings must be the supreme goal and the abiding practice of any Western society.

The first element of this individual liberty is the freedom of speech: the right to express and communicate ideas, to set oneself apart from the dumb beasts of field and forest; to recall governments to their duties and obligations; above all, the right to affirm one's membership and allegiance to the body politic — to society — to the men with whom we share our land, our heritage, and our children's future.

- Hand in hand with freedom of speech goes the power to be heard, to share in the decisions of government which shape men's lives. Everything that makes man's life worthwhile — family, work, education, a place to rear one's children and a place to rest one's head — all this depends on the decisions of government; all can be swept away by a government which does not heed the demands of its people, and I mean all of its people. Therefore, the essential humanity of men can be protected and preserved only where government must answer — not just to the wealthy, not just to those of a particular religion, or a particular race, but to all its people.

And even government by the consent of the governed, as in our own Constitution, must be limited in its power to act against its people; so that there may be no interference with the right to worship, or with the security of the home; no arbitrary imposition of pains or penalties by officials high or low; no restrictions on the freedom of men to seek education or work or opportunity of any kind, so that each man may become all he is capable of becoming.

These are the sacred rights of Western society.

- The road toward equality of freedom is not easy, and great cost and danger march alongside us. We are committed to peaceful and nonviolent change, and that is important for all to understand — though all change is unsettling. Still, even in the turbulence of protest and struggle is greater hope for the future, as men learn to claim and achieve for themselves the rights formerly petitioned from others.

And most important of all, all of the panoply of government power has been committed to the goal of equality before the law, as we are now committing ourselves to the achievement of equal opportunity in fact. We must recognize the full human equality of all of our people before God, before the law, and in the councils of government. We must do this, not because it is economically advantageous, although it is; not because the laws of God command it, although they do; not because people in other lands wish it so. We must do it for the single and fundamental reason that it is the right thing to do.

- All do not develop in the same manner, or at the same pace. Nations, like men, often march to the beat of different drummers, and the precise solutions of the United States can neither be dictated nor transplanted to others. What is important is that all nations must march toward increasing freedom; toward justice for all; toward a society strong and flexible enough to meet the demands of all its own people, and a world of immense and dizzying change.

- Only earthbound man still clings to the dark and poisoning superstition that his world is bounded by the nearest hill, his universe ends at river shore, his common humanity is enclosed in the tight circle of those who share his town or his views and the color of his skin.

It is — It is your job, the task of young people in this world, to strip the last remnants of that ancient, cruel belief from the civilization of man.

- Each nation has different obstacles and different goals, shaped by the vagaries of history and of experience. Yet as I talk to young people around the world I am impressed not by the diversity but by the closeness of their goals, their desires and their concerns and their hope for the future.

- I think that we could agree on what kind of a world we would all want to build. it would be a world of independent nations, moving toward international community, each of which protected and respected the basic human freedoms. It would be a world which demanded of each government that it accept its responsibility to insure social justice. It would be a world of constantly accelerating economic progress — not material welfare as an end in itself, but as a means to liberate the capacity of every human being to pursue his talents and to pursue his hopes. It would, in short, be a world that we would be proud to have built.

- The help and the leadership of South Africa or of the United States cannot be accepted if we, within our own country or in our relationships with others, deny individual integrity, human dignity, and the common humanity of man. If we would lead outside our borders, if we would help those who need our assistance, if we would meet our responsibilities to mankind, we must first, all of us, demolish the borders which history has erected between men within our own nations — barriers of race and religion, social class and ignorance.

Our answer is the world's hope; it is to rely on youth. The cruelties and the obstacles of this swiftly changing planet will not yield to obsolete dogmas and outworn slogans. It cannot be moved by those who cling to a present which is already dying, who prefer the illusion of security to the excitement and danger which comes with even the most peaceful progress. This world demands the qualities of youth: not a time of life but a state of mind, a temper of the will, a quality of the imagination, a predominance of courage over timidity, of the appetite for adventure over the love of ease.

- First, is the danger of futility: the belief there is nothing one man or one woman can do against the enormous array of the world's ills — against misery, against ignorance, or injustice and violence. Yet many of the world's great movements, of thought and action, have flowed from the work of a single man. A young monk began the Protestant Reformation, a young general extended an empire from Macedonia to the borders of the earth, and a young woman reclaimed the territory of France. It was a young Italian explorer who discovered the New World, and 32-year-old Thomas Jefferson who proclaimed that all men are created equal. "Give me a place to stand," said Archimedes, "and I will move the world." These men moved the world, and so can we all.

- Few will have the greatness to bend history, but each of us can work to change a small portion of the events, and then the total — all of these acts — will be written in the history of this generation.

- It is from numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped. Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

- The second danger is that of expediency: of those who say that hopes and beliefs must bend before immediate necessities. Of course, if we must act effectively we must deal with the world as it is. We must get things done. But if there was one thing that President Kennedy stood for that touched the most profound feeling of young people around the world, it was the belief that idealism, high aspirations, and deep convictions are not incompatible with the most practical and efficient of programs — that there is no basic inconsistency between ideals and realistic possibilities, no separation between the deepest desires of heart and of mind and the rational application of human effort to human problems. It is not realistic or hardheaded to solve problems and take action unguided by ultimate moral aims and values, although we all know some who claim that it is so. In my judgment, it is thoughtless folly. For it ignores the realities of human faith and of passion and of belief — forces ultimately more powerful than all of the calculations of our economists or of our generals. Of course to adhere to standards, to idealism, to vision in the face of immediate dangers takes great courage and takes self-confidence. But we also know that only those who dare to fail greatly, can ever achieve greatly.

- And a third danger is timidity. Few men are willing to brave the disapproval of their fellows, the censure of their colleagues, the wrath of their society. Moral courage is a rarer commodity than bravery in battle or great intelligence. Yet it is the one essential, vital quality of those who seek to change a world which yields most painfully to change.

- For the fortunate amongst us, the fourth danger, my friends, is comfort, the temptation to follow the easy and familiar paths of personal ambition and financial success so grandly spread before those who have the privilege of an education. But that is not the road history has marked out for us. There is a Chinese curse which says, "May he live in interesting times." Like it or not we live in interesting times. They are times of danger and uncertainty; but they are also more open to the creative energy of men than any other time in history. And everyone here will ultimately be judged — will ultimately judge himself — on the effort he has contributed to building a new world society and the extent to which his ideals and goals have shaped that effort.

Speech on the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1968)

What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black.

- Speech on the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (4 April 1968), delivered in Indianapolis, Indiana. Inscribed on the Robert F. Kennedy gravesite at Arlington National Cemetery

- Ladies and Gentlemen, I'm only going to talk to you just for a minute or so this evening, because I have some very sad news for all of you, and, I think, sad news for all of our fellow citizens, and people who love peace all over the world; and that is that Martin Luther King was shot and was killed tonight in Memphis, Tennessee.

- Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and to justice between fellow human beings. He died in the cause of that effort. In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it's perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are black -- considering the evidence evidently is that there were white people who were responsible -- you can be filled with bitterness, and with hatred, and a desire for revenge.

We can move in that direction as a country, in greater polarization -- black people amongst blacks, and white amongst whites, filled with hatred toward one another. Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand, and to comprehend, and replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand, compassion, and love. [...] But we have to make an effort in the United States. We have to make an effort to understand, to get beyond, or go beyond these rather difficult times.

- My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He wrote: "In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God."

- What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black.

- And let's dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world. Let us dedicate ourselves to that, and say a prayer for our country and for our people.

On the Mindless Menace of Violence (1968)

- This speech was given the day after the Martin Luther King, Jr. assassination. Delivered at the City Club of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio, April 5, 1968.

- The victims of the violence are black and white, rich and poor, young and old, famous and unknown. They are, most important of all, human beings whom other human beings loved and needed. No one — no matter where he lives or what he does — can be certain who will suffer from some senseless act of bloodshed. And yet it goes on and on and on in this country of ours.

- What has violence ever accomplished? What has it ever created? No martyr's cause has ever been stilled by an assassin's bullet. No wrongs have ever been righted by riots and civil disorders. A sniper is only a coward, not a hero; and an uncontrolled, uncontrollable mob is only the voice of madness, not the voice of reason. Whenever any American's life is taken by another American unnecessarily — whether it is done in the name of the law or in the defiance of the law, by one man or a gang, in cold blood or in passion, in an attack of violence or in response to violence — whenever we tear at the fabric of the life which another man has painfully and clumsily woven for himself and his children, the whole nation is degraded.

- Yet we seemingly tolerate a rising level of violence that ignores our common humanity and our claims to civilization alike. We calmly accept newspaper reports of civilian slaughter in far-off lands. We glorify killing on movie and television screens and call it entertainment. We make it easy for men of all shades of sanity to acquire whatever weapons and ammunition they desire.

- Too often we honor swagger and bluster and wielders of force; too often we excuse those who are willing to build their own lives on the shattered dreams of others. Some Americans who preach non-violence abroad fail to practice it here at home. Some who accuse others of inciting riots have by their own conduct invited them. Some look for scapegoats, others look for conspiracies, but this much is clear: violence breeds violence, repression brings retaliation, and only a cleansing of our whole society can remove this sickness from our soul.

- For there is another kind of violence, slower but just as deadly destructive as the shot or the bomb in the night. This is the violence of institutions; indifference and inaction and slow decay. This is the violence that afflicts the poor, that poisons relations between men because their skin has different colors. This is the slow destruction of a child by hunger, and schools without books and homes without heat in the winter. This is the breaking of a man's spirit by denying him the chance to stand as a father and as a man among other men. And this too afflicts us all.

- When you teach a man to hate and fear his brother, when you teach that he is a lesser man because of his color or his beliefs or the policies he pursues, when you teach that those who differ from you threaten your freedom or your job or your family, then you also learn to confront others not as fellow citizens but as enemies, to be met not with cooperation but with conquest; to be subjugated and mastered. We learn, at the last, to look at our brothers as aliens, men with whom we share a city, but not a community; men bound to us in common dwelling, but not in common effort. We learn to share only a common fear, only a common desire to retreat from each other, only a common impulse to meet disagreement with force.

- Yet we know what we must do. It is to achieve true justice among our fellow citizens. The question is not what programs we should seek to enact. The question is whether we can find in our own midst and in our own hearts that leadership of humane purpose that will recognize the terrible truths of our existence. We must admit the vanity of our false distinctions among men and learn to find our own advancement in the search for the advancement of others. We must admit in ourselves that our own children's future cannot be built on the misfortunes of others. We must recognize that this short life can neither be ennobled or enriched by hatred or revenge.

- Our lives on this planet are too short and the work to be done too great to let this spirit flourish any longer in our land. Of course we cannot vanquish it with a program, nor with a resolution. But we can perhaps remember, if only for a time, that those who live with us are our brothers, that they share with us the same short moment of life; that they seek, as do we, nothing but the chance to live out their lives in purpose and in happiness, winning what satisfaction and fulfillment they can. Surely, this bond of common faith, this bond of common goal, can begin to teach us something. Surely, we can learn, at least, to look at those around us as fellow men, and surely we can begin to work a little harder to bind up the wounds among us and to become in our own hearts brothers and countrymen once again.

Misattributed

- There are those that look at things the way they are, and ask why? I dream of things that never were, and ask why not?

- Though Kennedy stated that he was quoting George Bernard Shaw when he said this, he is often thought to have originated the expression, which actually paraphrases a line delivered by the Serpent in Shaw's play Back To Methuselah: “You see things; and you say, ‘Why?’ But I dream things that never were; and I say, ‘Why not?’". This phrase was first used by his brother John F. Kennedy in 1963 (June 28th), during his visit to Ireland, in his address to the Irish Dail (Government): "George Bernard Shaw, speaking as an Irishman, summed up an approach to life, 'Other people, he said, see things and say why? But I dream things that never were and I say, why not?" (Address on YouTube). Robert's other brother Edward famously quoted it (paraphrasing it even further), to conclude his eulogy to his late brother after his assassination (8 June 1968): Some men see things as they are and say why? I dream things that never were and say why not? - (Eulogy in CBS news video)

Quotes about Kennedy

The young man never says please. He never says thank you, he never asks for things, he demands them. ~ Adlai Stevenson.

- The young man never says please. He never says thank you, he never asks for things, he demands them.

- Adlai Stevenson referring to RFK. Cited in 1960: LBJ Vs. JFK Vs. Nixon : the Epic Campaign that Forged Three Presidencies (2008), p. 63.

- McCarthy was a Republican. The Democrats, however, have skeletons in their own closet and it's worth remembering them, too. For example, Democrat Woodrow Wilson's Attorney General, A. Mitchell Palmer, who was just as rabid an anti-Communist as McCarthy, did far more to repress free speech and political freedom than McCarthy ever attempted. It wasn't a Republican president who locked up thousands of loyal Americans of Japanese descent in concentration camps for years. It was Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt. And it wasn't a Republican who wiretapped and snooped on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., but Democrats John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert, who signed the order as Attorney General.

- Bruce Bartlett, as quoted in Wrong on Race: The Democratic Party's Buried Past (2008), by B. Bartlett, p. xi

- He sat down there on the side of the bed in an old broken-down building. Tears were running down his cheeks. I knew he cared. I can just see him sitting there and crying. The man had no vanity.

- Charles Evers on RFK, as quoted in the article "RFKennedy: Bobby, as We Knew Him" (6 June 1988)

- I wish people would stop turning him into Mother Theresa.

- Adam Walinsky on RFK in the article "RFKennedy: Bobby, as We Knew Him" (6 June 1988)

- The thing is, John and Bobby Kennedy are eternally young. The Democrats are trying to show us how young, and with it they are by reminding us of how things were 30 years ago.

- He never had a case in his life. He never argued in a courtroom. If you make him assistant secretary of defense, he'll have a lot of power. It's an appropriate job for a guy who has never done a damn thing.

- Senator, former U.S. attorney and Kennedy intimate George Smathers to JFK when told that RFK would be appointed attorney general. Recounted in an interview with Seymour Hersh and cited in The Dark Side of Camelot (1997)

- We had the impression that Bobby was simply Jack's ruffian. Jack could sit above it. Bobby was the one who wanted action. There was an intense dislike in CIA for Bobby.

- Former CIA official Walter Elder in an interview with Seymour Hersh, cited in The Dark Side of Camelot (1997)

- Bobby, in my view, was an unprincipled sinister little bastard.

- Former CIA official Thomas A. Parrot in a 1995 interview with Seymour Hersh, cited in The Dark Side of Camelot (1997)

- A child playing in a Dresden china shop.

- J. Edgar Hoover referring to RFK. Cited in Bobby and J. Edgar (2008) by Burton Hersh

- I was the East Coast distributor of involved. I ate it, drank it, and breathed it. Then they killed Martin, then they killed Bobby, elected Tricky Dick twice, and people like you must think I'm miserable because I'm not involved anymore. Well, I've got news for you. I spent all my misery years ago. I have no more pain for anything. I gave at the office.

- "Terence Mann" in Field of Dreams (1989), in the screenplay by Phil Alden Robinson, based upon the book Shoeless Joe (1982) by W. P. Kinsella

- He would dare us to leave yesterday and embrace tomorrow.

- Bill Clinton on Kennedy on the 25th anniversary of his death, as quoted in "Years. The Vision of Robert Kennedy Lives On." (6 June 1993)

- We still strive to answer his insistent challenge to do good and to do better.

- In a time of division, more than any American, he bridged those gaps, reaching out to starving families in the Mississippi Delta and to factory workers in Chicago, to migrant workers in Northern California and struggling teens in Harlem. He touched their lives. And just as important, they touched his.

- Bill Clinton on Kennedy on the 30th anniversary of his death, as quoted in "Clinton Urges Americans To Celebrate RFK's Legacy" (6 June 1998)

- Every four years, we've been bitterly frustrated by the failure of our candidates for the White House to live up to RFK's standards. Now that I am much older, I realize what I should have known in 1968 -- that Robert Kennedy was irreplaceable.

- Philip W. Johnston on Kennedy in the article "RFK: what we lost" (20 November 2005)

- As a U.S. Senator from New York and a presidential candidate, Robert F. Kennedy had the rhetorical ability to distill complex social ills into coherent moral stands. Whether he was talking about apartheid in South Africa during his trip there in June 1966, breaking a fast with Cesar Chavez in Delano, California, expressing the nation’s grief after Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed, or calling for an end to the Vietnam War, Robert Kennedy’s words could cut through social boundaries and partisan divides in a way that seems nearly impossible today.

- Joseph A. Palmero in article "Robert F. Kennedy Would Be 90 Years Old Today" (20 November 2015)

- His death left a vacuum that has not been filled. He had a capacity to reach out to disparate groups in our society: black and white, young and old, middle‐class and poor, blue‐collar workers and intellectuals. There is no political figure now, and none on the horizon, with whom so many Americans can identify.

- Robert Kennedy rejected comfort. He chose to be an uncomfortable man. It would have embarrassed him to hear such things said about himself. But he believed that individuals can make a difference if they care, and people knew he did. I think much would be different if he had lived.

- Anthony Lewis on RFK, as quoted in "Making a Difference" (4 June 1978)

- My father never retreated from shining a light on racial injustice. He forced hard conversations to play out in public, and pursued policies like the Voting Rights Act to specifically address the systemic racism plaguing our society. He realized that racism itself divided our country.

- Kerry Kennedy in article "Robert F. Kennedy and Racial Justice" (10 March 2016)

- His message, his voice, his attitude, his every appearance and intent were clear. He sought to make America great again.

- Mike Barnicle referring to RFK in article "What Bobby Kennedy Would Say To Trump" (13 March 2016)

- Robert Kennedy accomplished an extraordinary feat in his last campaign by uniting blacks and working whites in a way that no American politician has since been able to replicate.

- Kick Kennedy in article "How My Grandfather, RFK, Stopped a Riot" (4 April 2016)

- I come to this with tremendous humility. I was only seven when Bobby Kennedy died. Many of the people in this room knew him as brother, as husband, as father, as friend. I knew him only as an icon.

- People who believe that while evil and suffering will always exist, this is a country that has been fueled by small miracles and boundless dreams – a place where we’re not afraid to face down the greatest challenges in pursuit of the greater good; a place where, against all odds, we overcome. Bobby Kennedy was one of these people.

- And Kennedy’s was not a pie-in-the-sky-type idealism either. He believed we would always face real enemies, and that there was no quick or perfect fix to the turmoil of the 1960s. Rather, the idealism of Robert Kennedy – the unfinished legacy that calls us still – is a fundamental belief in the continued perfection of American ideals.

- Barack Obama at the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award ceremony commemorating the eightieth anniversary of RFK's birth (20 November 2005)

External links

- Annotated Bibliography for Robert F. Kennedy from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Text, Audio, and Video of Robert Kennedy's Address at Ball State University

- American Experience: RFK (PBS)

- Robert Kennedy's Remarks on the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr

- Excerpt of Robert Kennedy's Address at Cape Town University

- Edward Kennedy eulogy to Robert Kennedy (text and audio)

- Robert F. Kennedy on IMDb

- Profile at Find a Grave

- "My Father's Stand on Cuba Travel" by Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, The Washington Post (23 April 2009)

- Photos, videos, audio-clips and other RFK source materials from the U.S. National Archives.

References

This article is issued from

Wikiquote.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.