A politician is a person with whose politics you don't agree; if you agree with him he's a statesman.

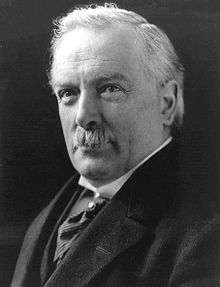

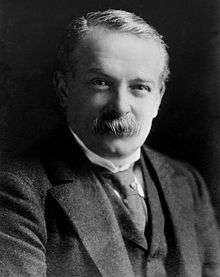

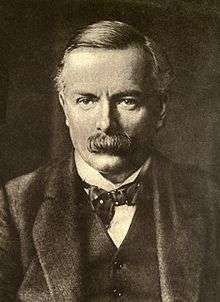

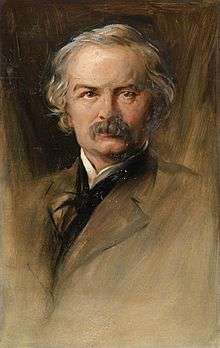

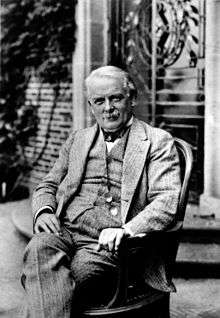

David Lloyd George (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was a British politician, who served as Prime Minister of United Kingdom (1916–1922).

Quotes

1880s

- I will not say but that I eyed the assembly in a spirit similar to that in which William the Conqueror eyed England on his visit to Edward the Confessor, as the region of his future domain. Oh, vanity!

- Diary entry (12 November 1881) after visiting the House of Commons, quoted in W. R. P. George, The Making of Lloyd George (1976), p. 101.

Backbench MP

A free religion and a free people in a free land.

- A free religion and a free people in a free land.

- Speech in Merthyr Tydfil (November 1890), quoted in Thomas Jones, Lloyd George (London: Oxford University Press, 1951), p. 11.

- Why had Wales made sacrifices in the face of unexampled difficulties and intimidation from squires and agents? It was not to install one statesman in power. It was not to deprive one party of power in order to put another party in power. It was not to transfer the emoluments of office from one statesman to another. No; it was done because Wales had by an overwhelming majority demonstrated its determination to secure its own progress. ... Welsh members wanted nothing for themselves but something for their country, and I do not think they would support a Liberal Ministry, I do not care how illustrious the Minister might be who led it, unless it pledged itself to concede to Wales those great measures of reform on which Wales had set its heart.

- Speech in Conway (c. late July 1892) after the 1892 general election, quoted in Thomas Jones, Lloyd George (London: Oxford University Press, 1951), pp. 16-17.

- [I believe in Oliver Cromwell] because he was a great fighting Dissenter. He was perhaps the first statesman to recognize that as soon as the Government became a democracy the Churches became directly responsible for any misgovernment. His great idea was to make Christ's law the law of the land, and any obstacle to this he ruthlessly swept away. How he would have dealt with Romish practices now! He said to the priest who babbled his Paternosters in Peterborough Cathedral, "Leave off your fooling and come down, sir." There was the man for the Ritualists (cheers)—worth a wagon-load of Bishops. How he would have dealt with the House of Lords! From the House of Commons he would have removed many a bauble, and he would have shaken his head and said, "The Lord deliver us from Joseph Chamberlain."

- Speech to the National Council of the Evangelical Free Churches at the City Temple, London (25 April 1899) for the 300th anniversary of Oliver Cromwell's birth, quoted in The Times (26 April 1899), p. 12.

- Mr. Chamberlain is right in so far as he says that things are not well in this country. We cannot feed the hungry with statistics of national prosperity, or stop the pangs of famine by reciting to a man the prodigious number of cheques that pass through the clearing-house. We must therefore propose something better than Mr. Chamberlain.

- Speech in the House of Commons (6 January 1904)

President of the Board of Trade

- I believe there is a new order coming for the people of this country. It is a quiet but certain revolution.

- Speech in Bangor, Wales (January 1906), quoted in Thomas Jones, Lloyd George (London: Oxford University Press, 1951), p. 34.

- [The House of Lords] is the right hon. Gentleman's poodle. It fetches and carries for him. It barks for him. It bites anybody that he sets it on to. And we are told that this is a great revising Chamber, the safeguard of liberty in the country. Talk about mockeries and shams. Was there ever such a sham as that?

- Speech in the House of Commons (26 June 1907)

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Liberty has restraints but no frontiers.

- Free Trade is a great pacificator. We have had many quarrels, many causes of quarrels, during the last fifty years, but we have not had a single war with any first-class Power. Free Trade is slowly but surely cleaving a path through the dense and dark thicket of armaments to the sunny land of brotherhood amongst nations.

- Speech in Manchester (21 April 1908), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 43.

- Free Trade may be the alpha, but it is not the omega, of Liberal policy.

- Speech in Manchester (21 April 1908), quoted in Thomas Jones, Lloyd George (London: Oxford University Press, 1951), p. 35.

- When I talk about trade and industry, it is not because I think trade and industry are more important than social reform. It is purely because I know that you must make wealth in the country before you can distribute it.

- Speech in Manchester (21 April 1908), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 46.

- I am a man of the people, bred amongst them, and it has been the greatest joy of my life to have had some part in fighting the battles of the class from whom I am proud to have sprung.

- Speech in Manchester (21 April 1908), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 46.

- ...the question of civil equality. We have not yet attained to it in this country—far from it. You will not have established it in this land until the child of the poorest parent shall have the same opportunity for receiving the best education as the child of the richest. ... It will never established so long as you have 500 men nominated by the lottery of birth to exercise the right of thwarting the wishes of the majority of 40 millions of their countrymen in the determination of the best way of governing the country.

- Speech in Swansea (1 October 1908), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 50.

- British Liberalism is not going to repeat the errors of Continental Liberalism. The fate of Continental Liberalism should warn them of that danger. It has been swept on one side before it had well begun its work, because it refused to adapt itself to new conditions. The Liberalism of the Continent concerned itself exclusively with mending and perfecting the machinery which was to grind corn for the people. It forgot that the people had to live whilst the process was going on, and people saw their lives pass away without anything being accomplished. But British Liberalism has been better advised. It has not abandoned the traditional ambition of the Liberal party to establish freedom and equality; but side by side with this effort it promotes measures for ameliorating the conditions of life for the multitude.

- Speech in Swansea (1 October 1908), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 51.

- All down history nine-tenths of mankind have been grinding the corn for the remaining tenth, and been paid with the husks and bidden to thank God they had the husk.

- Remark to Lucy Masterman (early 1909), quoted in Lucy Masterman, C. F. G. Masterman (Nicholson and Watson, 1939), p. 150.

- This, Mr. Emmot, is a war Budget. It is for raising money to wage implacable warfare against poverty and squalidness. I cannot help hoping and believing that before this generation has passed away, we shall have advanced a great step towards that good time, when poverty, and the wretchedness and human degradation which always follows in its camp, will be as remote to the people of this country as the wolves which once infested its forests.

- Budget speech in the House of Commons (29 April 1909)

- There have been two or three meetings held in the City of London...attended by the same class of people, but not ending up with a resolution promising to pay. On the contrary, we are spending the money, but they won't pay. What has happened since to alter their tone? Simply that we have sent in the bill. We started our four Dreadnoughts. They cost eight millions of money. We promised them four more; they cost another eight millions. Somebody has got to pay, and then these gentlemen say: "Perfectly true; somebody has got to pay, but we would rather that somebody were somebody else". We started building; we wanted money to pay for the building; so we sent the hat round. We sent it round amongst workmen, and the miners and weavers of Derbyshire and Yorkshire, and the Scotchmen of Dumfries, who, like all their countrymen, know the value of money, they all dropped in their coppers. We went round Belgravia, and there has been such a howl ever since that it has well-nigh deafened us.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 144.

- But they say, "It is not so much the Dreadnoughts we object to, it is pensions". If they objected to pensions, why did they promise them? They won elections on the strength of their promises. It is true they never carried them out. Deception is always a pretty contemptible vice, but to deceive the poor is the meanest of all.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 145.

Deception is always a pretty contemptible vice, but to deceive the poor is the meanest of all.

- The Budget...is introduced not merely for the purpose of raising barren taxes, but taxes that are fertile, taxes that will bring forth fruit—the security of the country which is paramount in the minds of all. The provision for the aged and deserving poor—was it not time something was done? It is rather a shame for a rich country like ours—probably the richest in the world, if not the richest the world has ever seen—should allow those who have toiled all their days to end in penury and possibly starvation. It is rather hard that an old workman should have to find his way to the gates of the tomb, bleeding and footsore, through the brambles and thorns of poverty. We cut a new path for him—an easier one, a pleasanter one, through fields of waving corn. We are raising money to pay for the new road—aye, and to widen it, so that 200,000 paupers shall be able to join in the march. There are so many in the country blessed by Providence with great wealth, and if there are amongst them men who grudge out of their riches a fair contribution towards the less fortunate of their fellow-countrymen they are very shabby rich men.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 145.

- There is another little tax called the increment tax. For the future what will happen? We mean to value all the land in the kingdom. And here you can draw no distinction between agricultural land and other land, for the simple reason that East and West Ham was agricultural land a few years ago. And if land goes up in the future by hundreds and thousands an acre through the efforts of the community, the community will get 20 per cent. of that increment.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 147.

- Take cases like Golder's Green and other cases of a similar kind where the value of land has gone up in the course, perhaps, of a couple of years through a new tramway or a new railway being opened. ... A few years ago there was a plot of land there which was sold at £160. Last year I went and opened a tube railway there. What was the result? This year that very piece of land has been sold for £2,100—£160 before the railway was opened—before I was there—£2,100 now. My Budget demands 20 per cent. of that.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 148.

- There are many cases where landlords take advantage of the needs of municipalities and even of national needs and of the monopoly which they have got in land in a particular neighbourhood in order to demand extortionate prices. Take the very well-known case of the Duke of Northumberland, when a county council wanted to buy a small plot of land as a site for a school to train the children who in due course would become the men labouring on his property. The rent was quite an insignificant thing; his contribution to the rates I think it was on the basis of 30s. an acre. What did he demand for it for a school? £900 an acre. All we say is this—if it is worth £900, let him pay taxes on £900.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 148.

- Now, all we say is this: "In future you must pay one halfpenny in the pound on the real value of your land. In addition to that, if the value goes up, not owing to your efforts—if you spend money on improving it we will give you credit for it—but if it goes up owing to the industry and the energy of the people living in that locality, one-fifth of that increment shall in future be taken as a toll by the State".

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 150.

- Who is the landlord? The Landlord is a gentleman … who does not earn his wealth. He does not even take the trouble to receive his wealth. He has a host of agents and clerks that receive it for him. He does not even take the trouble to spend his wealth. He has a host of people around him to do the actual spending for him. He never sees it until he comes to enjoy it. His sole function, his chief pride is stately consumption of wealth produced by others.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), pp. 150-151.

- The landlords are receiving eight millions a year by way of royalties. What for? They never deposited the coal in the earth. It was not they who planted these great granite rocks in Wales. Who laid the foundations of the mountains? Was it the landlord? And yet he, by some divine right, demands as his toll—for merely the right for men to risk their lives in hewing these rocks—eight millions a year.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), pp. 153-154.

The question will be asked whether five hundred men, ordinary men, chosen accidentally from among the unemployed, should override the judgment of millions of people who are engaged in the industry which makes the wealth of the country.

- ...yet when the Prime Minister and I knock at the door of these great landlords, and say to them: "Here, you know these poor fellows who have been digging up royalties at the risk of their lives, some of them are old, they have survived the perils of their trade, they are broken, they can earn no more. Won't you give them something towards keeping them out of the workhouse?" they scowl at us. We say, "Only a ha'penny, just a copper". They retort, "You thieves!" And they turn their dogs on to us, and you can hear their bark every morning. If this is an indication of the view taken by these great landlords of their responsibility to the people who, at the risk of life, create their wealth, then I say their day of reckoning is at hand.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), pp. 154-155.

- They go on threatening that if we proceed, they will cut down their benefactions and discharge labour. What kind of labour? What is the labour they are going to choose for dismissal? Are they going to threaten to devastate rural England by feeding and dressing themselves? Are they going to reduce their gamekeepers? Ah, that would be sad! The agricultural labourer and the farmer might then have some part of the game that is fattened by their labour. Also what would happen to you in the season? No week-end shooting with the Duke of Norfolk or anyone.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 155.

- The ownership of land is not merely an enjoyment, it is a stewardship. It has been reckoned as such in the past, and if the owners cease to discharge their functions in seeing to the security and defence of the country, looking after the broken in their villages and in their neighbourhoods, the time will come to reconsider the conditions under which land is held in this country.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 155.

- We are placing burdens on the broadest shoulders. Why should I put burdens on the people? I am one of the children of the people. I was brought up amongst them. I know their trials; and God forbid that I should add one grain of trouble to the anxieties which they bear with such patience and fortitude. When the Prime Minister did me the honour of inviting me to take charge of the National Exchequer at a time of great difficulty, I made up my mind, in framing the Budget which was in front of me, that at any rate no cupboard should be barer, no lot would be harder. By that test I challenge you to judge the Budget.

- Speech in Limehouse, East London (30 July 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 156.

- I lay down as a proposition that most of the people who work hard for a living in the country belong to the Liberal Party. I would say, and I think, without offence, that most of the people who never worked for a living at all belong to the Tory Party.

- Speech in Newcastle (9 October 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 160.

- A fully equipped Duke costs as much to keep up as two Dreadnoughts, and Dukes are just as great a terror, and they last longer.

- On the peers of the House of Lords, in a speech in Newcastle (9 October 1909), quoted in printed in the Manchester Guardian (11 October 1909)

- When I come along [to the landlord] and say, "Here, gentlemen, you have escaped long enough, it is your turn now, I want you to pay just 5 per cent. on the £10,000 odd," they reply:—"Five per cent? You are a thief; you are worse, you are an attorney; worst of all, you are a Welshman." That always is the crowning epithet. I do not apologize, and I do not mind telling you that if I could, I would not; I am proud of the little land among the hills...Whenever they hurl my nationality at my head, I say to them, "You Unionists, you hypocrites, Pharisees, you are the people who in every peroration...always talk about our being one kith and kin throughout the Empire...and yet if any man dares to aspire to any position, if he does not belong to the particular nationality which they have dignified by choosing their parents from, they have no use for him." Well, they have got to stand the Welshman now.

- Speech in Newcastle (9 October 1909), quoted in The Times (11 October 1909), p. 6

Who ordained that a few should have the land of Britain as a perquisite, who made 10,000 people owners of the soil and the rest of us trespassers in the land of our birth?

- Landlords have no nationality; their characteristics are cosmopolitan.

- Speech in Newcastle (9 October 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 168.

- We want money for the defence of the country, to provide pensions for the old people who have been spending their lives tilling the soil at a very poor pittance, in sinking those mines, and risking their lives, and when they are old we do not want to starve them or humiliate them—and we say what better use can you make of wealth than to use it for the purpose of picking up the broken, healing, curing the sick, bringing a little more light, comfort, and happiness to the aged? These men ought to feel honoured that Providence has given them the chance to put a little into the poor box. And since they will not do it themselves we have got to do it for them.

- Speech in Newcastle (9 October 1909), quoted in The Times (11 October 1909), p. 6

- If there is one thing more than another better established about the British Constitution it is this, that the Commons, and the Commons alone, have the complete control of supply and ways and means. And what our fathers established through centuries of struggles and of strife, even of bloodshed, we are not going to be traitors to. Who talks about altering and meddling with the Constitution? The Constitutional Party...As long as the Constitution gave rank and possession and power it was not to be interfered with. As long as it secured even their sports from intrusion, and made interference with them a crime; as long as the Constitution forced royalties and ground-rents and fees, premiums and fines, the black retinue of extraction; as long as it showered writs, and summonses, and injunctions, and distresses, and warrants to enforce them, then the Constitution was inviolate, it was sacred, it was something that was put in the same category as religion, that no man ought to touch, and something that the chivalry of the nation ought to range in defence of. But the moment the Constitution looks round, the moment the Constitution begins to discover that there are millions of people outside the park gates who need attention, then the Constitution is to be torn to pieces. Let them realize what they are doing. They are forcing revolution.

- Speech in Newcastle (9 October 1909), quoted in The Times (11 October 1909), p. 6

- The question will be asked, "Should 500 men, ordinary men, chosen accidentally from among the unemployed, override the judgment...of millions of people who are engaged in the industry which makes the wealth of the country?"

- On the House of Lords, speech in Newcastle (9 October 1909), quoted in The Times (11 October 1909), p. 6

- Who ordained that a few should have the land of Britain as a perquisite, who made 10,000 people owners of the soil and the rest of us trespassers in the land of our birth?

- Speech in Newcastle (9 October 1909), quoted in The Times (11 October 1909), p. 6

- Who is it who is responsible for the scheme of things whereby one man is engaged through life in grinding labour to win a bare and precarious subsistence for himself, and when, at the end of his days, he claims at the hands of the community he served a poor pension of eightpence a day, he can only get it through a revolution, and another man who does not toil receives every hour of the day, every hour of the night, whilst he slumbers, more than his poor neighbour receives in a whole year of toil? Where did the table of that law come from? Whose finger inscribed it? These are the questions that will be asked. The answers are charged with peril for the order of things the Peers represent; but they are fraught with rare and refreshing fruit for the parched lips of the multitude who have been treading the dusty road along which the people have marched through the dark ages which are now merging into the light.

- Speech in Newcastle (9 October 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), pp. 174-175.

- ...yet we are told that this great nation, with such a record of splendid achievements in the past and in the present, is unfit to make its own laws, is unfit to control its own finance, and that it is to be placed as if it were a nation of children or lunatics, under the tutelage and guardianship of some other body—and what body? Who are the guardians of this mighty people? Who are they? With all respect, I shall have to make exceptions; but I am speaking of them as a whole. ... They are men who have neither the training, the qualifications, nor the experience which would fit them for such a gigantic task. They are men whose sole qualification—speaking in the main, and for the majority of them—they are simply men whose sole qualification is that they are the first born of persons who had just as little qualification as themselves.

- Speech to the National Liberal Club (3 December 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), pp. 178-179.

- To invite this Imperial race; this, the greatest commercial nation in the world; this, the nation that has taught the world in the principles of self-government and liberty; to invite this nation itself to sign the decree that declares itself unfit to govern itself without the guardianship of such people, is an insult which I hope will be flung back with ignominy. This is a great issue. It is this: Is this nation to be a free nation and to become a freer one, or is it for all time to be shackled and tethered by tariffs and trusts and monopolies and privileges? That is the issue, and no Liberal will shirk it.

- Speech to the National Liberal Club (3 December 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 179.

Is this nation to be a free nation and to become a freer one, or is it for all time to be shackled and tethered by tariffs and trusts and monopolies and privileges? That is the issue, and no Liberal will shirk it.

- You must handle [the House of Lords] a little more firmly, and the time has come for unflinching and resolute action. For my part, I would not remain a member of a Liberal Cabinet one hour unless I knew that the Cabinet had determined not to hold office after the next General Election unless full powers are accorded to it which would enable it to place on the Statute Book of the realm a measure which will ensure that the House of Commons in future can carry, not merely Tory Bills, as it does now, but Liberal and progressive measures in the course of a single Parliament either with or without the sanction of the House of Lords.

- Speech to the National Liberal Club (3 December 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), pp. 179-180.

- But they have not rejected the Budget; they have only referred it to the people. On what principle do they refer Bills to the people? I remember the election of 1900, when a most powerful member of the Tory Cabinet said that the Nonconformists could vote with absolute safety for the Government, because no question in which they were interested would be raised. In two years there was a Bill destroying the School Boards. There was a Bill which drove Nonconformists into the most passionate opposition. What did the House of Lords do? Did they refer it to the people? Oh no, there was a vast difference between protecting the ground landlords in towns and protecting the village Dissenter. After all, the village Dissenter is too low down in the social scale for such exalted patronage, so he was left to the mercy of a Tory House of Commons without any of this high and powerful protection. Well, the Dissenters, despised as they may be, once upon a time taught a lesson to the House of Lords, and ere another year has passed they will be able to say, "Here endeth the second lesson" .

- Speech to the National Liberal Club (3 December 1909), quoted in Better Times: Speeches by the Right Hon. D. Lloyd George, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910), p. 189.

- Four spectres haunt the Poor — Old Age, Accident, Sickness and Unemployment. We are going to exorcise them. We are going to drive hunger from the hearth. We mean to banish the workhouse from the horizon of every workman in the land.

- Speech in Reading (1 January 1910)

- Personally I am a sincere advocate of all means which would lead to the settlement of international disputes by methods such as those which civilization has so successfully set up for the adjustment of differences between individuals.

But I am also bound to say this — that I believe it is essential in the highest interests, not merely of this country, but of the world, that Britain should at all hazards maintain her place and her prestige amongst the Great Powers of the world. Her potent influence has many a time been in the past, and may yet be in the future, invaluable to the cause of human liberty. It has more than once in the past redeemed Continental nations, who are sometimes too apt to forget that service, from overwhelming disaster and even from national extinction. I would make great sacrifices to preserve peace. I conceive that nothing would justify a disturbance of international good will except questions of the gravest national moment. But if a situation were to be forced upon us in which peace could only be preserved by the surrender of the great and beneficent position Britain has won by centuries of heroism and achievement, by allowing Britain to be treated where her interests were vitally affected as if she were of no account in the Cabinet of nations, then I say emphatically that peace at that price would be a humiliation intolerable for a great country like ours to endure.- Speech at Mansion House (21 July 1911) during the Agadir Crisis, quoted in The Times (22 July 1911), p. 7

- What has happened to the monastery? There it was planted in the hills, not merely looking after the spiritual needs of the people, but also their temporal needs...They have all gone. One of these parishes I find to-day with a tithe, and probably the land was owned by gentlemen who, when I was down there twenty years ago, was the anti-disestablishment candidate for that district. What is the good of talking about it? Whoever else has got a right to complain of Parliament not being authorised to deal with this trust; the present Establishment has no right, and the present House of Lords has no right. Property which was used for the sick, for the lame, for the poor, and for education, where has it gone to? ...the bulk of it went to the founders of great families. It is one of the most disgraceful and discreditable records in the history of this country.

- The Duke of Devonshire issues a circular applying for subscriptions to oppose this Bill, and he charges us with the robbery of God. Why, does he not know—of course he knows—that the very foundations of his fortune are laid deep in sacrilege, fortunes built out of desecrated shrines and pillaged altars...I say that charges of this kind brought against a whole people...ought not to be brought by those whose family trees are laden with the fruits of sacrilege. I am not complaining that ancestors of theirs did it, but they are still in the enjoyment of the same property, and they are subscribing out of that property to leaflets which attack us and call us thieves. What is their story? Look at the whole story of the pillage of the Reformation. They robbed the Catholic Church, they robbed the monasteries, they robbed the altars, they robbed the almshouses, they robbed the poor, and they robbed the dead. Then they come here when we are trying to seek, at any rate to recover some part of this pillaged property for the poor for whom it was originally given, and they venture, with hands dripping with the fat of sacrilege, to accuse us of robbery of God.

- They were now as a party engaged in carrying laboriously uphill the last few columns out of the Gladstonian quarry. ... Foremost among the tasks of Liberalism in the near future was the regeneration of rural life and the emancipation of the land of this country from the paralysing grip of an effete and unprofitable system. ... [The reports into rural life] were startling. When they were published they would prove conclusively that there were hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of men, women, and children dependent upon the land in this country and engaged in cultivating it, hardworking men and women, who were living under conditions with regard to wages, to housing, as well as hours of labour—conditions which ought to make this great Empire hang its head in shame that such things could be permitted to happen in any corner of its vast dominions, let alone in this country, the centre and source of all its glory.

- Speech to the National Liberal Club (31 January 1913), quoted in The Times (1 February 1913), p. 8.

- This rich, proud Empire did not pay its children, who had maintained and built up its glory and upon whom they had to depend in future against every foe, enough to keep themselves, their wives, and their children above a state of semi-starvation. (Cries of "Shame.") The land of Britain, which ought to be rearing a virile, healthy, independent, prosperous people, was held under conditions which positively discouraged capital, enterprise, and brains, sapped independence and undermined vitality. The condition of things was one which demanded the immediate attention of every man who loved his native land and who had any heart to sympathize with humanity in despair.

- Speech to the National Liberal Club (31 January 1913), quoted in The Times (1 February 1913), p. 8.

- I could multiply instances of men, women, and children who have been just snatched from the jaws of the grave by this Act of Parliament, and yet whilst it is walking the streets, hurrying about on its errand of mercy, visiting the sick, healing those who are afflicted with disease, feeding hungry children whose parents have been prostrated by sickness and cannot look after them—whilst it is doing the work of the Man of Nazareth in the stricken homes of Britain, it is being stoned by Tory speakers, reviled, insulted, and spat upon. Their reckoning is piling up. It will soon be demanded at their hands to the last penny by a people who have been misled by them into disdaining one of the greatest gifts the Imperial Parliament has ever delivered to the people of this land.

- Speech to the Nottinghamshire Miners' Association (10 August 1913) on the National Insurance Act 1911, quoted in The Times (11 August 1913), p. 10.

- Success to your meetings. Future of this country depends on breaking up the land monopoly—it withers the land, depresses wages, destroys independence, and drives millions into dwellings which poison their strength. Godspeed to every effort to put an end to this oppression.

- Telegram to a national conference to promote the taxation and rating of land held in Cardiff (13 October 1913), quoted in The Times (14 October 1913), p. 10

- Labourers had diminished, game had tripled. The landlord was no more necessary to agriculture than a gold chain to a watch.

- Speech (late 1913), quoted in Thomas Jones, Lloyd George (London: Oxford University Press, 1951), p. 45.

- There are always clouds in the international sky. You never get a perfectly blue sky in foreign affairs. And there are clouds even now. But we feel confident that the common sense, the patience, the good-will, the forbearance which enabled us to solve greater and more difficult and more urgent problems last year will enable us to pull through these difficulties at the present moment.

- Speech at the City of London (17 July 1914), quoted in The Times (18 July 1914), p. 10

- The right hon. Gentleman the Member for West Birmingham said, in future what are you going to tax when you will want more money? He also not merely assumed but stated that you could not depend upon any economy in armaments. I think that is not so. I think he will find that next year there will be substantial economy without interfering in the slightest degree with the efficiency of the Navy. The expenditure of the last few years has been very largely for the purpose of meeting what is recognised to be a temporary emergency. ... It is very difficult for one nation to arrest this very terrible development. You cannot do it. You cannot when other nations are spending huge sums of money which are not merely weapons of defence, but are equally weapons of attack. I realise that, but the encouraging symptom which I observe is that the movement against it is a cosmopolitan one and an international one. Whether it will bear fruit this year or next year, that I am not sure of, but I am certain that it will come. I can see signs, distinct signs, of reaction throughout the world. Take a neighbour of ours. Our relations are very much better than they were a few years ago. There is none of that snarling which we used to see, more especially in the Press of those two great, I will not say rival nations, but two great Empires. The feeling is better altogether between them. They begin to realise they can co-operate for common ends, and that the points of co-operation are greater and more numerous and more important than the points of possible controversy.

- Speech in the House of Commons on the day the Austrian ultimatum was sent to Serbia (23 July 1914); The "neighbour" mentioned is Germany.

- The stern hand of fate has scourged us to an elevation where we can see the great everlasting things which matter for a nation — the great peaks we had forgotten, of Honor, Duty, Patriotism, and clad in glittering white, the great pinnacle of Sacrifice pointing like a rugged finger to Heaven.

- Speech, Queen's Hall, London (19 September 1914)

- What are ten, twenty, or thirty millions when the British Empire is at stake? This is an artillery war. We must have every gun we can lay hands upon.

- Quoted in Lord Riddell's diary entry (13 October 1914), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 92

- A ramshackle old empire.

- Speech of 1914; quoted in The Brunswick and Coburg Leader (16 October 1914). The "empire" mentioned is Austria-Hungary.

- [Lloyd George] was still pessimistic about the war—said we were fighting better brains than our own—that there was not one really first-class man on our side. The Germans had shown that they had better training than we, and he knew the value of training—he had seen examples of it in the House of Commons, when Labour members competed against men of better education than themselves—they were just as good fellows, but they hadn't the training. And [Lloyd George] says that it is training that is wanting on our side—among the generals. He says our soldiers are the best in Europe, but they are being wantonly sacrificed because those in authority do not know how to make the best use of them.

- Frances Stevenson's diary entry (16 December 1914), A. J. P. Taylor (ed.), Lloyd George: A Diary (London: Hutchinson, 1971), p. 17

- The Government were on the look-out for a good, strong business man, with some push and go in him, who will be able to put the thing through.

- Speech in the House of Commons (9 March 1915) on the Defence of the Realm (Amendment) Bill, quoted in The Times (10 March 1915), p. 14

Minister of Munitions

It is a strange irony, but no small compensation, that the making of weapons of destruction should afford the occasion to humanise industry.

- We won and saved our liberties in this land on more than one occasion by compulsory service. France saved the liberty she had won in the great Revolution from the fangs of tyrannical military empires purely by compulsory service; the great Republic of the West won its independence and saved its national existence by compulsory service, and two of the greatest countries of Europe to-day—France and Italy—are defending their national existence and liberties by means of compulsory service. It has been the greatest weapon in the hands of Democracy many a time for the winning and preservation of freedom.

- Speech in Manchester (3 June 1915), quoted in The Times (4 June 1915), p. 9

- We are are a very individualistic nation. ... Individualism has its merits in producing strong, independent, virile nations; but in war individualism has its manifold defects. ... [T]he nation has not yet concentrated one-half of its industrial strength on the problem of carrying this great conflict through successfully. It is a war of munitions. We are fighting against the best organized community in the world—the best organized, whether for war or for peace—and we have been employing too much of the haphazard, leisurely, go-as-you-please methods which, believe me, would not have enabled us to maintain our place as a nation, even in peace, very much longer.

- Speech in Manchester (3 June 1915), quoted in The Times (4 June 1915), p. 9

- Practically the whole of the engineering establishments of this country were controlled by the State. He had seen resolutions passed by the Trades Congress about the nationalization of industry, but the Government had done it.

- Speech to the Trades Union Congress in Bristol (9 September 1915), quoted in The Times (10 September 1915), p. 10

- It is a strange irony, but no small compensation, that the making of weapons of destruction should afford the occasion to humanise industry. Yet such is the case. Old prejudices have vanished, new ideas are abroad; employers and workers, the public and the State, are favourable to new methods. This opportunity must not be allowed to slip. It may well be that, when the tumult of war is a distant echo, and the making of munitions a nightmare of the past, the effort now being made to soften asperities, to secure the welfare of the workers, and to build a bridge of sympathy and understanding between employer and employed, will have left behind results of permanent and enduring value to the workers, to the nation and to mankind at large.

- Speech (February 1916), quoted in War Memoirs: Volume I (London: Odhams, 1938), pp. 209-210

- I have been told that I am a traitor to Liberal principles because I supported Conscription. ... Every great democracy which has been challenged, which has had its liberties menaced, has defended itself by resort to compulsion, from Greece downwards. Washington won independence for America by compulsory measures; they defended it in 1812 by compulsory measures. Lincoln...proclaimed the principle of "Government of the People, by the People, for the People," and he kept it alive by Conscription. In the French Revolution the French people defended their newly-obtained liberties against every effort of the Monarchists by compulsion. ... France is defending her country to-day by Conscription. In Italy the Italian Democracy are seeking to redeem their enthralled brethren by compulsion.

- Speech in the House of Commons (4 May 1916) during the Second Reading of the Bill introducing compulsory military service

Secretary of State for War

- The British soldier is a good sportsman. He enlisted in this war in a sporting spirit—in the best sense of that term. He went in to see fair play to a small nation trampled upon by a bully. He is fighting for fair play. He has fought as a good sportsman. By the thousands he has died a good sportsman. He has never asked anything more than a sporting chance. He has not always had that. When he couldn't get it, he didn’t quit. He played the game. He didn’t squeal, and he has certainly never asked anyone to squeal for him. Under the circumstances the British, now that the fortunes of the game have turned a bit, are not disposed to stop because of the squealing done by Germans or done for Germans by probably well-meaning but misguided sympathizers and humanitarians...During these months when it seemed the finish of the British Army might come quickly, Germany elected to make this a fight to a finish with England. The British soldier was ridiculed and held in contempt. Now we intend to see that Germany has her way. The fight must be to a finish—to a knock-out.

- Interview with Roy Howard of the United Press of America (28 September 1916), quoted in The Times (29 September 1916), p. 7

- Any intervention now would be a triumph for Germany! A military triumph! A war triumph! Intervention would have been for us a military disaster. Has the Secretary of State for War no right to express an opinion upon a thing which would be a military disaster? That is what I did, and I do not withdraw a single syllable. It was essential. I could tell the hon. Member how timely it was. I can tell the hon. Member it was not merely the expression of my own opinion, but the expression of the opinion of the Cabinet, of the War Committee, and of our military advisers. It was the opinion of every ally. I can understand men who conscientiously object to all wars. I can understand men who say you will never redeem humanity except by passive endurance of every evil. I can understand men, even—although I do not appreciate the strength of their arguments—who say they do not approve of this particular war. That is not my view, but I can understand it, and it requires courage to say so. But what I cannot understand, what I cannot appreciate, what I cannot respect, is when men preface their speeches by saying they believe in the war, they believe in its origin, they believe in its objects and its cause, and during the time the enemy were in the ascendant never said a word about peace; but the moment our gallant troops are climbing through endurance and suffering up the path of ascendancy begin to howl with the enemy.

- Speech in the House of Commons (11 October 1916)

- He won't fight the Germans but he will fight for Office.

- His opinion of Asquith's attempts to stay in power during the political crisis that ousted him from the premiership, quoted in Frances Stevenson's diary entry (5 December 1916), A. J. P. Taylor (ed.), Lloyd George: A Diary (London: Hutchinson, 1971), p. 133

Prime Minister

The correspondents don't write and the censorship wouldn't pass the truth. What they do send is not the war, but just a pretty picture of the war with everybody doing gallant deeds. The thing is horrible and beyond human nature to bear and I feel I can't go on with this bloody business.

- Haig does not care how many men he loses. He just squanders the lives of these boys. I mean to save some of them in the future. He seems to think they are his property. I am their trustee. I will never let him rest. I will raise the subject again & again until I nag him out of it—until he knows that as soon as the casualty lists get large he will get nothing but black looks and scowls and awkward questions...I should have backed Nievelle against Haig. Nievelle has proved himself to be a Man at Verdun; & when you get a Man against one who has not proved himself, why, you back the Man!

- Quoted in Frances Stevenson's diary entry (15 January 1917), A. J. P. Taylor (ed.), Lloyd George: A Diary (London: Hutchinson, 1971), p. 139

- The old hide-bound Liberalism was played out; the Newcastle programme [of 1891] had been realised. The task now was to build up the country.

- Quoted by C. P. Scott in his diary (26 January 1917), in Trevor Wilson (ed.), The Political Diaries of C. P. Scott, 1911-1928 (London: Collins, 1970), p. 257

- Do these things for the sake of your country during the war. Do them for the sake of your country after the war. When the smoke of this great conflict has been dissolved in the atmosphere we breathe there will reappear a new Britain. It will be the old country still, but it will be a new country. Its commerce will be new, its trade will be new, its industries will be new. There will be new conditions of life and of toil, for capital and for labour alike, and there will be new relations between both of them and for ever. (Cheers.) But there will be new ideas, there will be a new outlook, there will be a new character in the land. The men and women of this country will be burnt into fine building material for the new Britain in the fiery kilns of the war. It will not merely be the millions of men who, please God! will come back from the battlefield to enjoy the victory which they have won by their bravery—a finer foundation I would not want for the new country, but it will not be merely that—the Britain that is to be will depend also upon what will be done now by the many more millions who remain at home. There are rare epochs in the history of the world when in a few raging years the character, the destiny, of the whole race is determined for unknown ages. This is one. The winter wheat is being sown. It is better, it is surer, it is more bountiful in its harvest than when it is sown in the soft spring time. There are many storms to pass through, there are many frosts to endure, before the land brings forth its green promise. But let us not be weary in well-doing, for in due season we shall reap if we faint not. (Loud cheers.)

- Speech in his constituency of Carnavon Boroughs (3 February 1917), quoted in The Times (5 February 1917), p. 12

- [Lloyd George] was very pleased last night, for he had given the soldiers a dressing-down in the morning. He was dealing with Haig's demand for more men & informed them that Haig would get no more than had already been decided upon. 'He does not make the best use of his men. Let him learn to make better use of them. There is no danger now on land. The danger is on sea'.

- Frances Stevenson's diary entry (14 February 1917), A. J. P. Taylor (ed.), Lloyd George: A Diary (London: Hutchinson, 1971), p. 144

- ...in the northeastern portion of Ireland you have a population as hostile to Irish rule as the rest of Ireland is to British rule, yea, and as ready to rebel against this as the rest of Ireland is against British rule. ... As alien in blood, in religious faith, in traditions, in outlook—as alien from the rest of Ireland in this respect as the inhabitants of Fife or Aberdeen. It is no use mincing words. Let us have a clear understanding. To place them under national rule against their will would be as glaring an outrage on the principles of liberty and self-government as the denial of self-government would be for the rest of Ireland.

- Speech in the House of Commons (7 March 1917)

- [Proportional representation is a] device for defeating democracy, the principle of which was that the majority should rule, and for bringing faddists of all kinds into Parliament, and establishing groups and disintegrating parties.

- Quoted by C. P. Scott in his diary (3 April 1917), in Trevor Wilson (ed.), The Political Diaries of C. P. Scott, 1911-1928 (London: Collins, 1970), p. 274

- "I warn you", said Lloyd George, "that I am in a very pacifist temper". I listened last night, at a dinner given to Philip Gibbs on his return from the front, to the most impressive and moving description from him of what the war really means that I have heard. Even an audience of hardened politicians and journalists was strongly affected. The thing is horrible and beyond human nature to bear and "I feel I can't go on with this bloody business: I would rather resign."

- Quoted by C. P. Scott in his diary (28 December 1917), in Trevor Wilson (ed.), The Political Diaries of C. P. Scott, 1911-1928 (London: Collins, 1970), p. 324

- The statistics given me by Sir Auckland Geddes are most disquieting. They show that the physique of the people of this country is far from what it should be, particularly in the agricultural districts where the inhabitants should be the strongest. That is due to low wages, malnutrition and housing. It will have to be put right after the war. I have always stood during the whole of my life for the under-dog. I have not changed, and am going still to fight his battle.

- Quoted in Lord Riddell's diary entry (13/14 August 1918), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 233

- ...we must profit by the lessons of the war. ... the first lesson it has taught is the immense importance of maintaining the solidarity of the British Empire. (Cheers.) It has rendered a service to humanity the magnitude of which will appear greater and greater as this generation recedes into the past. ... This Empire has never been such a power for good. To suggest that such an organization could fall to pieces after the war would be a crime against civilization. ... The British Empire will be needed after peace to keep wrongs in check. Its mere word will count more next time than it did the last. For the enemy know now what they have got to deal with.

- Speech in Manchester (12 September 1918), quoted in The Times (13 September 1918), p. 8

- What is the next great lesson of the war? It is that if Britain has to be thoroughly equipped to meet any emergencies of either war or peace it must take a more constant and a more intelligent interest in the health and fitness of the people. ... I solemnly warn my fellow-countrymen that you cannot maintain an A1 Empire with a C3 population. (Cheers.) Unless this lesson is learned the war is in vain. Remember that the health of the people is the secret of national efficiency and national recuperation.

- Speech in Manchester (12 September 1918), quoted in The Times (13 September 1918), p. 8

- The State must help to promote and encourage production. ... There must be none of that shrinking from national organization, national production, and national assistance. Germany never made that mistake. Take the most important of national industries, agriculture. Agriculture in the past has been overlooked in this country. It has been neglected, with the result that we have been dependent very largely on lands across the seas for our food. We have realized during the war the perils of this position. ... It is in the highest interests of the community that the land in this country should be cultivated to its fullest capacity, and I doubt whether there is a civilized country in the whole world where agriculture has received less attention at the hands of the State. ... The cultivation of the land is the basis of national strength and prosperity.

- Speech in Manchester (12 September 1918), quoted in The Times (13 September 1918), p. 8

- ...the shielding of industries which have been demonstrated by the war to be essential to the very life of the nation. I remember when I was appointed Minister of Munitions I found there were industries essential to national defence which had been very largely captured by our enemies. ... these essential key industries shall be preserved after the war, not because we anticipate another war, but because we are less likely to have another war if they know that we are quite ready for any challenge on a just ground.

- Speech in Manchester (12 September 1918), quoted in The Times (13 September 1918), p. 8

- Wilson is adopting a dangerous line. He wants to pose as the great arbiter of the war. His Fourteen Points are very dangerous. He speaks of the freedom of the seas. That would involve the abolition of the right of search and seizure, and the blockade. We shall not agree to that. Such a change would not suit this country. Wilson does not see that by laying down terms without consulting the Allies, he is making their position very difficult. He had no right to reply to the German Note without consultation, and I insisted upon a cablegram being sent to him. The position is very disturbing.

- Quoted in Lord Riddell's diary entry (10 October 1918), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 240

- I have already accepted the policy of Imperial preference...to the effect that a preference will be given on existing duties and on any duties which may subsequently be imposed. On this subject I think there is no difference of opinion between us. ... I am prepared to say that the key industries on which the life of the nation depends must be preserved. I am prepared to say also that, in order to keep up the present standard of production and develop it to the utmost extent possible, it is necessary that security should be give against the unfair competition to which our industries have been in the past subjected by the dumping of goods below the actual cost of production. ... I shall look at every problem simply from the point of view of what is the best method of securing the objects at which we are aiming without any regard to theoretical opinions about Free Trade or Tariff Reform.

- Letter to Andrew Bonar Law (2 November 1918), quoted in The Times (18 November 1918), p. 4

- Great Britain would spend her last guinea to keep a navy superior to that of the United States or any other power.

- Quoted in Colonel Edward House's diary entry (4 November 1918), quoted in Charles Seymour (ed.), The Intimate Papers of Colonel House. Volume IV (Boston, 1928), p. 180

The finest eloquence is that which gets things done; the worst is that which delays them.

- At eleven o’clock this morning came to an end the cruellest and most terrible War that has ever scourged mankind. I hope we may say that thus, this fateful morning, came to an end all wars.

- Speech in the House of Commons (11 November 1918)

- Diplomats were invented simply to waste time.

- On preparation for the Paris Peace Conference (November 1918)

- What is our task? To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in.

- Speech in Wolverhampton (23 November 1918), quoted in The Times (25 November 1918), p. 13

- ...what about those people whom we received without question for years to our shores (Voices.—“Send them back”), who, after we did so and gave them equal rights with the sons and daughters of our own households, abused hospitality to betray the land that received them; to plot against its security, to spy upon it, and to supply information and weapons that enabled the Prussian War Lords to inflict, not punishment, but to inflict damage and injury, on the land which had received them. Never again! (Mr. Lloyd George here banged the table in front of him, and the audience cheered vociferously.)

- Speech in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (29 November 1918), quoted in The Times (30 November 1918), p. 6

- There is one point I had overlooked as to the question of the responsibility for the invasion of Belgium and the conduct of the war. The Government asked the Attorney-General to refer the question to some of the greatest jurists in this country. They have investigated it, and have come finally to the conclusion quite unanimously that in their judgment the Kaiser was guilty of an indictable offence for which he ought to be held responsible.

- Speech in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (29 November 1918), quoted in The Times (30 November 1918), p. 6

- Trial of the Kaiser; punishment of those responsible for atrocities; fullest indemnities from Germany; Britain for the British, socially and industrially; rehabilitation of those broken in the war; and a happier country for all.

- Election programme contained in a foreword to an official list of Coalition candidates, quoted in The Times (11 December 1918), p. 8

- ...the question of indemnity. (Cheers.) Who is to foot the bill? (A voice—“Germany.”) I am again going to talk to you quite frankly about this. By the jurisprudence of every civilized country in the world, in any lawsuit the loser pays. It is not a question of vengeance, it is a question of justice.

- Speech in Colston Hall, Bristol (11 December 1918), quoted in The Times (12 December 1918), p. 6

- ...I have always said we will exact the last penny we can out of Germany up to the limit of her capacity, but I am not going to mislead the public on the question of the capacity until I know more about it, and I am not going to do it in order to win votes. It is not right; it is not fair; it is not straightforward; and it is not honest. If Germany has a greater capacity, she must pay to the very last penny.

- Speech in Colston Hall, Bristol (11 December 1918), quoted in The Times (12 December 1918), p. 6

- The finest eloquence is that which gets things done; the worst is that which delays them.

- Speech at the Paris Peace Conference (January 1919)

- I am making a good fight for the old country & there is no one but me who could do it.

- Quoted in Frances Stevenson's diary entry (11 March 1919), A. J. P. Taylor (ed.), Lloyd George: A Diary (London: Hutchinson, 1971), p. 171

- We must make, if we can, an enduring peace. That is why I feel so strongly regarding the proposal to hand over two million Germans to the Poles, who are an inferior people so far as concerns the experience and capacity for government. We do not want to create another Alsace-Lorraine.

- Quoted in Lord Riddell's diary entry (28 March 1919), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 262

- The truth is that we have got our way. We have got most of the things we set out to get. If you had told the British people twelve months ago that they would have secured what they have, they would have laughed you to scorn. The German Navy has been handed over; the German mercantile shipping has been handed over, and the German colonies have been given up. One of our chief trade competitors has been most seriously crippled and our Allies are about to become her biggest creditors. That is no small achievement. In addition, we have destroyed the menace to our Indian possessions.

- Quoted in Lord Riddell's diary entry (30 March 1919), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 263

- I had to tell him quite plainly that the Belgians had lost only 16,000 men in the war, and that, when all was said, Belgium had not made greater sacrifices than Great Britain. The truth is that we are always called upon to foot the bill. When anything has to be done it is "Old England" that has to do it. If the Rumanians have to be supplied with food and credits have to be given, in the final result England has to stand the racket. It is time that we again told the world what we have done. These things tend to be forgotten. Our policy is quite clear but imperfectly understood. We mean that the French shall have coal in the Saar Valley and that the Poles shall have access to the sea through Danzig; but we don't want to create a condition of affairs that will be likely to lead to another war. We don't want to place millions of Germans under the domination of the French and the Poles. That would not be for their benefit, and what is the use of setting up a lot of Alsace-Lorraines?

- Quoted in Lord Riddell's diary entry (31 March 1919), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), pp. 263-264

- Those insolent Germans made me very angry yesterday. I don't know when I have been more angry. Their conduct showed that the old German is still there. Your Brockdorff-Rantzaus will ruin Germany's chances of reconstruction. But the strange thing is that the Americans and ourselves felt more angry than the French and Italians. I asked old Clemenceau why. He said, "Because we are accustomed to their insolence. We have had to bear it for fifty years. It is new to you and therefore it makes you angry".

- Quoted in Lord Riddell's diary entry (8 May 1919), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 275. At the opening of a conference the day before, the German delegate Count Brockdorff-Rantzau unexpectedly made a speech that was regarded as tactless.

- Dumping is the exporting to this country of goods from a foreign land under the cost—beneath the price at which they are sold in their own country. There could be only one object in doing that, and that is to make war upon a particular industry in our country. That is unfair. ... In the interests of fairness, as well as in the interests of British industry as a whole, the Government have decided to submit to Parliament proposals which will effectively deal with dumping in the sense in which I have defined it.

- Speech in the House of Commons (18 August 1919)

- I sometimes wish that I were in the Labour Party. I would tear down all these institutions!

- Speaking of landlords, quoted in Frances Stevenson's diary entry (17 December 1919), A. J. P. Taylor (ed.), Lloyd George: A Diary (London: Hutchinson, 1971), p. 193

- Not badly, considering I was seated between Jesus Christ and Napoleon.

- Comment about Woodrow Wilson and Georges Clemenceau, when asked, in 1919 upon his return from the Paris Peace Conference, as to how he had done there; as quoted in the article "International Relations" in The New Encyclopaedia Britannica (1993)

Not badly, considering I was seated between Jesus Christ and Napoleon.

- Winston [Churchill] is the only remaining specimen of a real Tory.

- Quoted in Frances Stevenson's diary entry (17 January 1920), A. J. P. Taylor (ed.), Lloyd George: A Diary (London: Hutchinson, 1971), p. 197

- We have murder by the throat.

- On the Irish Republican Army, in a speech at Guildhall, London (9 November 1920), quoted in The Times (10 November 1920), p. 12

- We are offering Ireland not subjection but equality, not servitude but partnership.

- Speech at Guildhall, London (9 November 1920), quoted in The Times (10 November 1920), p. 12

- The League of Nations is the greatest humbug in history. They cannot even protect a little nation like Armenia. They do nothing but pass useless resolutions.

- Quoted in Lord Riddell's diary entry (18 December 1920), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 330

- [Lloyd George] said that Harding's speech on American naval aspirations made him feel that he would pawn his shirt rather than allow America to dominate the seas. If this was to be the outcome of the League of Nations propaganda, he was sorry for the world and in particular for America.

- Lord Riddell's diary entry (1 January 1921), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 332

- [Lloyd George] then went on to say that the Imperial Conference had had a meeting that morning, and that he, Smuts, Hughes and Massey did not intend to allow the British Empire to take a back seat. Gt Britain had won the war. She had made enormous sacrifices in men and money, and they were quite determined that she should not be overshadowed by America.

- Lord Riddell's diary entry (July 1921), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 330

- The B[ritish] E[mpire] is a sisterhood of nations—the greatest in the world. Look at this table: There sits Africa—English and Boer; there sits Canada—French, Scotch & English; there sits Australia, representing many races—even Maoris; there sits India; here sit the representatives of England, Scotland & Wales; all we ask you to do is to take your place in this sisterhood of free nations. It is an invitation, Mr. De Valera: we invite you here.

- Quoted in Frances Stevenson's diary entry (14 July 1921), A. J. P. Taylor (ed.), Lloyd George: A Diary (London: Hutchinson, 1971), pp. 227-228

- [Lloyd George] saw [Eamon de Valera] again on Friday [15 July]... He (DeV.) insisted that what the people of Ireland wanted was a republic, & asked [Lloyd George] if the name of republic could not be conceded at any rate. [Lloyd George] replied that that was just what they cold not have—that the people of this country would not tolerate it after all that had happened. 'There must be some other word', said [Lloyd George]. 'After all, it is not an Irish word. What is the word for republic in Irish?' 'Poblacht', was DeV.'s reply. 'That merely means "people",' said [Lloyd George]. 'Isn't there another word?' 'Saorstaat', said DeV. 'Very well', said [Lloyd George]. 'Why do you insist upon Republic? Saorstaat is good enough!' [Lloyd George] said that for the first time DeV. simply roared with laughter.

- Frances Stevenson's diary entry (18 July 1921), A. J. P. Taylor (ed.), Lloyd George: A Diary (London: Hutchinson, 1971), p. 228.

- [Lloyd George] had a not too satisfactory interview with [Eamon de Valera] yesterday. ... After DeV. had read the terms he told [Lloyd George] he could not advise his people to accept them. 'Very well, Mr. DeV.', was [Lloyd George]'s answer, 'then there is only one thing more left for us to discuss'. 'What is that?', asked DeV. 'The time for the truce to come to an end', said [Lloyd George]. [Lloyd George] says DeV. went perfectly white, and had difficulty controlling his agitation. ... [Lloyd George] says that if they refuse there is only one thing to be done—to reconquer Ireland.

- Frances Stevenson's diary entry (22 July 1921), A. J. P. Taylor (ed.), Lloyd George: A Diary (London: Hutchinson, 1971), pp. 230-231.

We are offering Ireland not subjection but equality, not servitude but partnership.

- I am not going to bind myself to the cart-tail of a lot of capitalists. It may be unpleasant to take the money of one plutocrat in exchange for an honour, but when all is said, nothing very serious happens. Whereas if a political party is financed by great trade interests, who want something for their money, the result is certain to be very serious, as no public question would be considered on its merits.

- Quoted in Lord Riddell's diary entry (2 July 1922), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 370.

- I shall make it quite plain that if there is to be an enquiry, it will have to begin with Lord Salisbury's administration, or at any rate with Arthur Balfour's. ... I don't defend the system, but I have done merely what other Prime Ministers have done, and I am going to make it clear that if I am going down, I am going to bring the temple down with me. I am not going to be sacrificed by people and the descendants of people who have been engaged in carrying on precisely the same system.

- On his sale of honours, quoted in Lord Riddell's diary entry (8 July 1922), J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908-1923 (London: The Athlone Press, 1986), p. 371.

- He is the best living embodiment of the Liberal doctrine that quality is not hereditary.

- Speech in Manchester (14 October 1922) on the son of W. E. Gladstone, Viscount Gladstone, quoted in The Times (16 October 1922), p. 17

- It is always a mistake to threaten unless you mean it, and it is because not merely we threatened, but we meant it, and the Turks knew that we meant it, that you have peace now.

- Speech in Manchester (14 October 1922) referring to the Chanak Crisis, quoted in The Times (16 October 1922), p. 17

Later life

- In the war we had got out of the danger of the military spirit in Europe trampling upon human liberty, and were now confronted with a menace from inside our own country—such a menace as had destroyed Russia. That menace was an attack upon the very life-blood of Britain, and unless it was arrested at the start, the whole fabric of the commerce, trade, and prosperity of this country would come down and Britain the mighty, whose name ringed round the earth, would become a poor thing.

- Speech in Haverfordwest (10 November 1922) during the general election campaign, quoted in The Times (11 November 1922), p. 12

- The issue was whether they were going to maintain our present economic structure, with improvements ameliorating its asperities gradually and cautiously, or whether they were going to pull the whole thing down, to put the whole of our commerce and industry into the melting-pot, at a moment when everything depended on credit and confidence, and absolutely destroy these things by committing the country to a wild series of proposals. Put compendiously, the proposal of the Labour Party was, "The nation is suffering from lack of capital; let us take what there is." (Laughter.) The old idea of bleeding a patient, abandoned by the medical profession, was taken up by the Labour Party. Even the doctors never bled a patient who was suffering from anaemia, yet that was what the Labour Party proposed. It was the stupidest programme ever put before the electorate.

- Speech in Bristol (14 November 1922), quoted in The Times (15 November 1922), p. 14

- Of all the bigotries that savage the human temper there is none so stupid as the anti-Semitic.

- Is it Peace (1923)

- [Lloyd George] had always felt that they thought that in him they had a kindred spirit. That was true. Their great men were the men he admired; some of their greatest men were the men from whom he had drawn inspiration, notably Abraham Lincoln. The next day he was to start on a journey to see a country which he regarded as the great miracle of the West, where man had risen from the dead past to a new hope.

- Speech to the American Society in London at the Savoy Hotel, London (28 September 1923) before his tour of the United States, quoted in The Times (29 September 1923), p. 6

- My right hon. Friend says she [Germany] is in such a condition that she cannot possibly pay [reparations]. No, she cannot pay us. She is to pay France in full. Everything goes to France, everything goes to Italy, everything goes to Belgium; but, forsooth, she has not the capacity to pay Great Britain. I object. We were equal in the sacrifices we had to make, and I think it is about time that someone should stand up for the rights of Great Britain.

- Speech in the House of Commons (6 March 1924)

- It was a treaty which might have been signed by a vanquished Power as far as British interests were concerned.

- Speech in the House of Commons (9 April 1924) against the Treaty of Lausanne, quoted in The Times (10 April 1924), p. 7

- The time has come for Liberalism to resume the leadership of progress—to lead away the masses from the chimeras of Karl Marx and the nightmares of Lenin, and to carry on the great task to which Gladstone and Bright devoted their noble lives.

- Speech in Queen's Hall, Langham Place (14 October 1924) opening the Liberal Party's election campaign, quoted in The Times (15 October 1924), p. 10

- This is a Government of to-morrow. ... It is all swagger and pose, and no action. Let it be done. No, he cannot do it, he is too busy doing other things. Russia must come first. No time to carry schemes for the unemployed, no time to deal with profiteering in food and in materials for building. ... Yet there was time for a Russian loan. Moscow first, and Camberwell afterwards.

- Speech in Camberwell, London (27 October 1924) attacking Ramsay MacDonald's Labour Government, quoted in The Times (28 October 1924), p. 8

- This is a Vote to spend £58,000,000 in protection of our trade routes. Our trade routes are in danger, but they are not in danger from navies. ... They are not naval, they are not military, they are not aerial; they are industrial, and the First Lord of the Admiralty has within the last few days been brought face to face with far and away the greatest danger to our trade routes. It is not in the Pacific; it is at home. It is no use sweeping the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean in order to see whether you can somehow or other find dangers to guard against. The danger is yawning in front of us, and the Government are marching into it, scanning the horizon with telescope glued to one eye, and the other closed.

- Speech in the House of Commons (29 July 1925)

- We are met together this afternoon under the shadow of a grave industrial conflict of unknown magnitude. Apart altogether from the merits of the dispute, every citizen will feel it his duty to support the Government of to-day in the maintenance of order and in the organizing and facilitating of the essential services of the nation. (Cheers.) The country must come first always and all the time. It is very deplorable and all the more deplorable because in my honest judgment it was unnecessary.

- Speech in Cambridge (1 May 1926) on the General Strike, quoted in The Times (3 May 1926), p. 9

- I am making no predictions and the Prime Minister is wise in taking that line, but I am perfectly certain that nothing will enable the German Empire for a generation or two to get anywhere near the same position of dominant force and menace that it was in before the War. I do not say they desire it—I do not believe there is any such desire in Germany at the present moment.

- Speech in the House of Commons (27 March 1928)

- Liberty is not merely a privilege to be conferred; it is a habit to be acquired.

- Speech in the House of Commons (10 May 1928)

- Liberty has restraints but no frontiers.

- International Liberal Conference (July 1928)

- Sincerity is the surest road to confidence.

- Speech at Aberystwyth (3 August 1928)

- Germany has carried out her obligations. She was to reduce her army to 100,000. She was to scrap her great artillery and all her machinery of war. ... Germany had carried out her obligations. That was over three years ago. What have we done? What have the Allies done to carry out that obligation? ... Disarmament is the only guarantee of safety. ... Germany is demanding, and rightly demanding, that we should now carry out our obligations, seeing that she has carried out her's. ... The whole of the British Empire signed that bond, every part of it. When it is asked to carry it out, what is it to say? Is it to say, "We are treating you exactly as we are treating France—you with your army of 100,000 and France with her army of millions"? Is the British Empire to say, "We are treating you impartially and fairly"? Shall Caesar send a lie?

- Speech in the House of Commons (13 November 1928)