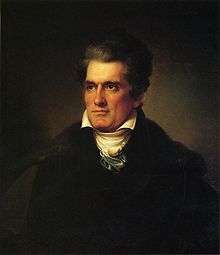

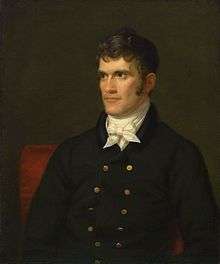

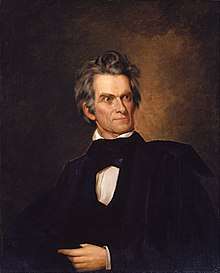

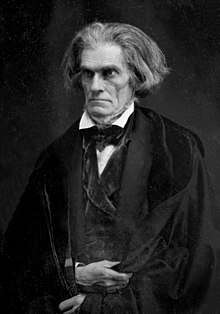

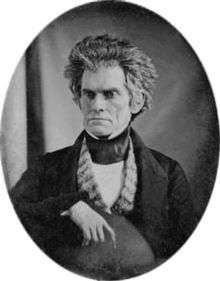

John Caldwell Calhoun (18 March 1782 – 31 March 1850) was an American politician from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. A Democrat who supported slavery, he served as the seventh Vice President of the United States, first under John Quincy Adams (1825–1829) and then under Andrew Jackson (1829–1832), but resigned the Vice Presidency to enter the United States Senate, where he had more power. He also served in the United States House of Representatives (1810–1817) and was both Secretary of War (1817–1824) and Secretary of State (1844–1845).

Quotes

1810s

- Protection and patriotism are reciprocal.

- Speech in the House of Representatives (12 December 1811)

- The neighboring tribes are becoming daily less warlike, and more helpless and dependent on us … [T]hey have, in a great measure, ceased to be an object of terror, and have become that of commiseration.

- Speech to the House of Representatives (5 December 1818)

1830s

- The Government of the absolute majority instead of the Government of the people is but the Government of the strongest interests; and when not efficiently checked, it is the most tyrannical and oppressive that can be devised.

- Speech to the U.S. Senate (15 February 1833)

- The very essence of a free government consists in considering offices as public trusts, bestowed for the good of the country, and not for the benefit of an individual or a party.

- Speech (13 February 1835)

- A power has risen up in the government greater than the people themselves, consisting of many and various and powerful interests, combined into one mass, and held together by the cohesive power of the vast surplus in the banks.

- Speech (27 May 1836); this is the source of the phrase, "Cohesive power of public plunder"

- I hold that the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding states between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good. A positive good.

- Many in the South once believed that slavery was a moral and political evil. That folly and delusion are gone. We see it now in its true light, and regard it as the most safe and stable basis for free institutions in the world.

- Regarding slavery (1838), as quoted in Brother Against Brother: The War Begins, (The Civil War series) vol. 1, William C. Davis, New York, NY, Time-Life Books, (1983) p. 40

1840s

- I cannot think in the present state of parties of entering again on the political arena. I would but waste my strength and exhaust my time, without adding to my character, or rendering service to the country, or advancing the cause for which I have so long contended. I feel no disgust nor do I feel disposed to complain of any one. On the contrary, I am content, and willing to end my public life now. In looking back, I see nothing to regret, and little to correct. My interest in the prosperity of the country, and the success of our peculiar and sublime political system when well understood, remain without abatement, and will do so till my last breath; and I shall ever stand prepared to serve the country, whenever I shall see reasonable prospect of doing so.

- Letter to Duff Green (10 February 1844), in Correspondence of John C. Calhoun (1900) edited by William Pinkney Starke, p. 569

- Our well-founded claim, grounded on continuity, has greatly strengthened, during the same period, by the rapid advance of our population toward the territory — its great increase, especially in the valley of the Mississippi — as well as the greatly increased facility of passing to the territory by more accessible routes, and the far stronger and rapidly-swelling tide of population that has recently commenced flowing into it.

- Letter to Richard Pakenham, British minister to the United States, concerning the boundary dispute between the two countries (3 September 1844)

- I am a Southern man and a slaveholder. A kind and merciful one, I trust, and none the worse for being a slaveholder. I say, for one, I would rather meet any extremity upon earth than give up one inch of our equality, one inch of what belongs to us as members of this republic! What! Acknowledged inferiority! The surrender of life is nothing to sinking down into acknowledged inferiority!

- Speech in the U.S. Senate (19 February 1847)

- It is harder to preserve than to obtain liberty.

- Speech in the Senate (January 1848)

- The cords that bind the States together are not only many, but various in character. Some are spiritual or ecclesiastical; some political; others social... The strongest are those of a spiritual and ecclesiastical nature, consisted in the unity of the great religious denominations, all of which originally embraced the whole Union. All these denominations, with the exception, perhaps, of the Catholics, were organized very much upon the principle of our political institutions. Beginning with smaller meetings, corresponding with the political divisions of the country, their organization terminated in one great central assemblage, corresponding very much with the character of Congress. At these meetings the principal clergymen and lay members of the respective denominations, from all parts of the Union, met to transact business relating to their common concerns. It was not confined to what appertained to the doctrines and discipline of the respective denominations, but extended to plans for disseminating the Bible, establishing missionaries, distributing tracts, and of establishing presses for the publication of tracts, newspapers, and periodicals, with a view of diffusing religious information, and for the support of the doctrines and creeds of the denomination. All this combined contributed greatly to strengthen the bonds of the Union.

- Speech on the Oregon Bill, 1848

- With us the two great divisions of society are not the rich and the poor, but white and black, and all the former, the poor as well as the rich, belong to the upper class, and are respected and treated as equals, if honest and industrious, and hence have a position and pride of character of which neither poverty nor misfortune can deprive them.

- Speech in the U.S. Senate (12 August 1849)

1850s

- The interval between the decay of the old and the formation and establishment of the new constitutes a period of transition which must always necessarily be one of uncertainty, confusion, error, and wild and fierce fanaticism.

- A Disquisition on Government (1851), p. 90

- I assume, as an incontestable fact, that man is so constituted as to be a social being. His inclinations and wants, physical and moral, irresistibly impel him to associate with his kind; and he has, accordingly, never been found, in any age or country, in any state other than the social. In no other, indeed, could he exist; and in no other—were it possible for him to exist—could he attain to a full development of his moral and intellectual faculties, or raise himself, in the scale of being, much above the level of the brute creation. I next assume, also, as a fact not less incontestable, that, while man is so constituted as to make the social state necessary to his existence and the full development of his faculties, this state itself cannot exist without government. The assumption rests on universal experience. In no age or country has any society or community ever been found, whether enlightened or savage, without government of some description.

- A Disquisition on Government (1851)

- To the Infinite Being, the Creator of all, belongs exclusively the care and superintendence of the whole. He, in his infinite wisdom and goodness, has allotted to every class of animated beings its condition and appropriate functions; and has endowed each with feelings, instincts, capacities, and faculties, best adapted to its allotted condition. To man, he has assigned the social and political state, as best adapted to develop the great capacities and faculties, intellectual and moral, with which he has endowed him; and has, accordingly, constituted him so as not only to impel him into the social state, but to make government necessary for his preservation and well-being.

- A Disquisition on Government (1851)

- It is a great and dangerous error to suppose that all people are equally entitled to liberty. It is a reward to be earned, not a blessing to be gratuitously lavished on all alike—a reward reserved for the intelligent, the patriotic, the virtuous and deserving—and not a boon to be bestowed on a people too ignorant, degraded and vicious, to be capable either of appreciating or of enjoying it. Nor is it any disparagement to liberty, that such is, and ought to be the case. On the contrary, its greatest praise—its proudest distinction is, that an all-wise Providence has reserved it, as the noblest and highest reward for the development of our faculties, moral and intellectual. A reward more appropriate than liberty could not be conferred on the deserving—nor a punishment inflicted on the undeserving more just, than to be subject to lawless and despotic rule.

- A Disquisition on Government (1851)

- Such a state [of individual freedom and equality] is purely hypothetical. It never did, nor can exist; as it is inconsistent with the preservation and perpetuation of the race. It is, therefore, a great misnomer to call it the state of nature. Instead of being the natural state of man, it is, of all conceivable states, the most opposed to his nature—most repugnant to his feelings, and most incompatible with his wants. His natural state is, the social and political—the one for which his Creator made him, and the only one in which he can preserve and perfect his race. As, then, there never was such a state as the, so called, state of nature, and never can be, it follows, that men, instead of being born in it, are born in the social and political state; and of course, instead of being born free and equal, are born subject, not only to parental authority, but to the laws and institutions of the country where born, and under whose protection they draw their first breath.

- A Disquisition on Government (1851)

Attributed to John C. Calhoun

- I never know what South Carolina thinks of a measure. I never consult her. I act to the best of my judgment, and according to my conscience. If she approves, well and good. If she does not, or wishes any one to take my place, I am ready to vacate. We are even.

- Reported in Walter J. Miller, "Calhoun as a Lawyer and Statesman"' part 2, The Green Bag (June 1899), p. 271. Miller states "I will cite his own words", but this quotation is reported as not verified in Calhoun's writings in Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations (1989).

Disputed

- Beware the wrath of a patient adversary.

- This has recently become attributed to Calhoun on the internet and in print, but seems to be a derivative of John Dryden's statement in Absalom and Achitophel (1681): Beware the Fury of a Patient Man.

Quotes about John C. Calhoun

- John Calhoun, if you secede from my nation I will secede your head from the rest of your body.

- Andrew Jackson, said to John C. Calhoun, in reference to his proposed secession of South Carolina from the United States during the Nullification Affair

This quotation is fraudulent. It comes with no attribution, and there is nothing like it anywhere in the actual record of Jackson's exchanges with Calhoun, both written and verbal. Further, the expression "my nation" is one that Jackson never did use or would have used --Daniel Feller, Editor/Director, The Papers of Andrew Jackson.

- Stephens' Constitutional View of the War Between the States, which was and remains probably the best defense of the Confederate cause. It is all about states' rights, and the defense of the minority against the tyranny of the numerical majority, although the 'silent minority', the four million slaves, are never counted. It is substantially the book that Calhoun would have written had he been alive to do so... Calhoun was the philosopher-king of the old south, the spiritual mentor of Stephens, Davis, and most of the political leaders of the Confederacy. Bradford and McClellan, following Willmoore Kendall, are obsessed with the utterly false notion that Lincoln was somehow responsible for the permissive egalitarianism of the contemporary welfare state. But equality as such was no less important to Calhoun than to Lincoln. It was just a different kind of equality... It never occurs to Calhoun that black human beings might also resent, with equal, or much greater, reason, 'acknowledged inferiority'. That is because he does not think of them as human. Calhoun simply assumes that blacks have neither the reason nor the passions that are characteristically human. They are chattels, that is, cattle, for all intents and purposes.

- Harry V. Jaffa, "Defending the Cause of Human Freedom" (15 April 1994), The Claremont Institute, The Claremont Institute

- Calhoun's last speech had a bitter attack on Mr. Jefferson for his amendment to the Ordinance of '87 prohibiting slavery in the Northwest Territory. Calhoun was in a dying condition – was too weak to read it. So James M. Mason, a Virginia Senator, read it in the Senate about two weeks before Calhoun's death, March 1850.

- John S. Mosby, letter to Samuel "Sam" Chapman (4 June 1907)

- The first protective tariff in American history was introduced by Calhoun and supported by Madison and Jefferson, and opposed by Webster... Calhoun divorced the idea of states' rights from natural rights, and invented the doctrine of legal or constitutional 'secession' to replace the natural right of revolution as the ground for independence. The South understood that to appeal to the right of revolution, as Jefferson had in the Declaration, was necessarily to appeal to the idea of individual natural rights. Southern leaders balked at such an appeal, because they understood that natural rights flew in the face of their fantastic justifications for slavery.

- Thomas L. Krannawitter, "Dishonest About Abe" (10 May 2002), Claremont Review of Books, The Claremont Institute

- Calhoun is remembered for what he did in the latter half of his adult life. In those years, he rationalized slavery, suppressed freedom of speech, and legitimized secession.

- James Loewen, "Celebrating John C. Calhoun in Minnesota!" (23 July 2015), History News Network