Freedom and power bring responsibility.

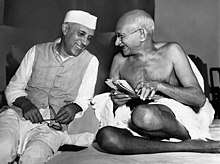

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian politician and the first Prime Minister of India .

Quotes

The most effective pose is one in which there seems to be the least of posing, and Jawahar had learned well to act without the paint and powder of an actor … What is behind that mask of his?

Crises and deadlocks when they occur have at least this advantage, that they force us to think.

We must constantly remind ourselves that whatever our religion or creed, we are all one people.

Peace is not only an absolute necessity for us in India in order to progress and develop but also of paramount importance to the world.

War itself is not the objective; victory is not the objective; you fight to remove the obstruction that comes in the way of your objective. If you let victory become the end in itself then you've gone astray and forgotten what you were originally fighting about.

Ultimately what we really are matters more than what other people think of us.

I have become a queer mixture of the East and the West … Out of place everywhere, at home nowhere.

Without peace, all other dreams vanish and are reduced to ashes.

Democracy and socialism are means to an end, not the end itself.

Culture is the widening of the mind and of the spirit. It is never a narrowing of the mind or a restriction of the human spirit or the country's spirit.

- We believe that it is the inalienable right of the Indian people, as of any other people, to have freedom and to enjoy the fruits of their toil and have the necessities of life, so that they may have full opportunities of growth. We believe also that if any government deprives a people of these rights and oppresses them the people have a further right to alter it or abolish it. The British government in India has not only deprived the Indian people of their freedom but has based itself on the exploitation of the masses, and has ruined India economically, politically, culturally and spiritually. We believe therefore, that India must sever the British connection and attain Purna Swaraj or complete independence.

- Nehru wrote this resolution of Purna Swaraj (Complete Independence), which was adopted in the Congress session at Lahore on 26 January 1930; this was later celebrated as Independence Day until August 1947, and after 26 January 1950 as Republic Day; as quoted in India (1999) by Stanley A. Wolpert

- Religion is not familiar ground for me, and as I have grown older, I have definitely drifted away from it. I have something else in its place, something older than just intellect and reason, which gives me strength and hope. Apart from this indefinable and indefinite urge, which may have just a tinge of religion in it and yet is wholly different from it, I have grown entirely to rely on the workings of the mind. Perhaps they are weak supports to rely upon, but, search as I will, I can see no better ones.

- Letter to Mahatma Gandhi (1933), as quoted in "Nehru's Faith" by Sunil Khilnani, in The New Republic (24 May 2004), p. 27

- The most effective pose is one in which there seems to be the least of posing, and Jawahar had learned well to act without the paint and powder of an actor … What is behind that mask of his? … what will to power? … He has the power in him to do great good for India or great injury … Men like Jawaharlal, with all their capacity for great and good work, are unsafe in a democracy.

He calls himself a democrat and a socialist, and no doubt he does so in all earnestness, but every psychologist knows that the mind is ultimately slave to the heart … Jawahar has all the makings of a dictator in him — vast popularity, a strong will, ability, hardness, an intolerance for others and a certain contempt for the weak and inefficient … In this revolutionary epoch, Caesarism is always at the door. Is it not possible that Jawahar might fancy himself as a Caesar? … He must be checked. We want no Caesars.- Article in Modern Review (1936) by a pseudonymous author signing himself "Chanakya", later revealed to have been Nehru himself; as quoted in TIME magazine : "Clear-Eyed Sister" (3 January 1955) & "The Uncertain Bellwether" (30 July 1956)

- Great causes and little men go ill together.

- The Indian Annual Register Vol.1 (January-June 1939)

- Most of us seldom take the trouble to think. It is a troublesome and fatiguing process and often leads to uncomfortable conclusions. But crises and deadlocks when they occur have at least this advantage, that they force us to think.

- The Unity of India : Collected Writings, 1937-1940 (1942), p. 94

- Because we have sought to cover up past evil, though it still persists, we have been powerless to check the new evil of today.

Evil unchecked grows, Evil tolerated poisons the whole system. And because we have tolerated our past and present evils, international affairs are poisoned and law and justice have disappeared from them.- The Unity of India : Collected Writings, 1937-1940 (1942), p. 280

- They fought because they were paid for it; they were not interested very much in the conquest of Greece. The Athenians on the other hand, fought for their freedom. They preferred to die rather than lose their freedom, and those who are prepared to die for any cause are seldom defeated.

- On the defeat of the forces of Darius the Great of Persia at the Battle of Marathon, in Glimpses of World History; Being Further Letters to His Daughter, Written In Prison, And Containing A Rambling Account of History For Young People (1942); also in Nehru on World History (1960} edited by Saul K. Padover, p. 14

- We must constantly remind ourselves that whatever our religion or creed, we are all one people. I regret that many recent disturbances have given us a bad name. Many have acquiesced to the prevailing spirit. This is not citizenship. Citizenship consists in the service of the country. We must prevail on the evil-doers to stop their activities. If you, men of the Navy, the Army and the Air Force, serve your countrymen without distinction of class and religion, you will bring honour to yourselves and to your country.

- Radio address to the Defence Services (1 December 1947)

- In times of crisis it is not unnatural for those who are involved in it deeply to regard calm objectivity in others as irrational, short-sighted, negative, unreal or even unmanly. But I should like to make it clear that the policy India has sought to pursue is not a negative and neutral policy. It is a positive and vital policy that flows from our struggle for freedom and from the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. Peace is not only an absolute necessity for us in India in order to progress and develop but also of paramount importance to the world. How can that peace be preserved? Not by surrendering to aggression, not by compromising with evil or injustice but also not by the talking and preparing for war! Aggression has to be met, for it endangers peace. At the same time, the lesson of the past two wars has to be remembered and it seems to me astonishing that, in spite of that lesson, we go the same way. The very processes of marshaling the world into two hostile camps precipitates the conflict that it had sought to avoid. It produces a sense of terrible fear and that fear darkens men's minds and leads them to wrong courses. There is perhaps nothing so bad and so dangerous in life as fear. As a great President of the United States said, there is nothing really to fear except fear itself.

- Speech at Columbia University (1949); published in Speeches 1949 - 1953 p. 402; as quoted in Sources of Indian Tradition (1988) by Stephen Hay, p. 350

- Wars are fought to gain a certain objective. War itself is not the objective; victory is not the objective; you fight to remove the obstruction that comes in the way of your objective. If you let victory become the end in itself then you've gone astray and forgotten what you were originally fighting about.

- Interview by James Cameron, in Picture Post (28 October 1950)

- If in the modern world wars have unfortunately to be fought (and they do, it seems) then they must be stopped at the first possible moment, otherwise they corrupt us, they create new problems and make our future even more uncertain. That is more than morality; it's sense.

- Interview by James Cameron in Picture Post (28 October 1950)

- "I am the last Englishman to rule India"

- Nehru to Prof Galbraith. Quoted from Nehru: The Hero That Was

- Ultimately what we really are matters more than what other people think of us. One has to face the modern world with its good as well as its bad and it is better on the whole, I think, that we give even licence than suppress the normal flow of opinion. That is the democratic method. But having laid that down, still I would beg to say that there is a limit to the licence that one can allow, more so in times of great peril to the State.

- Parliamentary Debates [Parliament of India] Pt.2 V.12-13 (1951); also quoted in Glorious Thoughts of Nehru (1964), p. 146

- [When asked in 1963 that "now that there is Communist government in Kerala, what would happen if communists came to power at the Centre?"] - Communists, communists! Why are you all so obsessed with communism and communists? What is that the communists can do what we cannot do and have not done?... Why do you imagine the communists will ever be voted to power at the Centre? The danger to India, mark you, is not Communism. It is Hindu right-wing communalism.

- (Jawaharlal Nehru, a Biography; by Sankar Ghose, p 180.) Also quoted in part in Nehru: The Invention of India: Shashi Tharoor, and in S. Balakrishna, Seventy years of secularism.

- Communalism of the majority is far more dangerous than that of a minority. The majority, by virtue of it's being a majority, has the strength to have its way: it requires no protection. It is a most undesirable custom to give statutory protection to minorities. It is sometimes for example, to backward classes, but it is not good in the long run. I do not say that the majority should accept the wrong things done by the minority. How can it do so? (But) It is the duty and responsibility of the majority community, whether in the matter of language or religion, to pay particular attention to what the minority wants and to win it over. The majority is strong enough to crush the minority, which might not be protected.

- The majority community must show generosity in the matter to allay the fear and suspicion that minorities, even though unreasonably, might have.

- When the minority communities are communal, you can see that and understand it. But the communalism of a majority community is apt to be taken for nationalism.

- We have thus communalism ingrained in us and it comes out quickly even at the slightest provocation and even decent people begin to behave like barbarians when communalism is aroused in them.

- We still have these ideas of casteism and communalism with us, whether we are Hindus or Muslims or Sikhs. The communal and caste weaknesses of the people had been deprecated in numerous resolutions of the Congress Working Committee and AICC. 'These resolutions were against these caste and communal tendencies.' Yet, in our daily life, we do not understand them fully. If a lot is said about these weaknesses, it hurts people.

- If we cannot forget these caste and communal weaknesses, which erupt in us at the slightest provocation, and cannot tolerate other communities, then to hell with Swarajya.

- During his various speeches; taken from: "The Muslims of India: A Documentary Record", A.G. Noorani ; Jawaharlal Nehru's Speeches Vol. 3 (1953-1957); Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru Vol. 7.

- I want to go rapidly towards my objective. But fundamentally even the results of action do not worry me so much. Action itself, so long as I am convinced that it is right action, gives me satisfaction. In my general outlook on life I am a socialist and it is a socialist order that I should like to see established in India and the world.

- Statement of 1951, in Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru Vol. 5 (1987), p. 321

- Sir...In the early hours of this morning Marshal Stalin passed away... When we think of Marshal Stalin, all kinds of thoughts come to...my mind...looking back at these 35 years or so, many figures stand out, but perhaps no single figure has moulded and affected and influenced the history of these years more than Marshal Stalin. He became gradually almost a legendary figure, sometimes a man of mystery, at other times a person who had an intimate bond not with a few but with vast numbers of persons. He proved himself great in peace and in war. He showed an indomitable will and courage which few possess...here was a man of giant stature...who ultimately would be remembered by the way he built up his great country...but the fact remains of his building up that great country, which was a tremendous achievement, and in addition to that the remarkable fact...is that he was not only famous in his generation but...he was in a sense ‘intimate’...with vast numbers of human beings, not only the vast numbers in the Soviet Union with whom he moved in an intimate way, in a friendly way, in an almost family way...So here was this man who created in his life-time this bond of affection and admiration among vast numbers of human eings...But every one must necessarily agree about his giant stature and about his mighty achievements. So it is right that we should pay our tribute to him on this occasion because the occasion is not merely the passing away of a great figure but...in the sense of the ending of a certain era in history...Some...describe him as...[a] gentle person... Marshal Stalin was something much more than the head of a State. He was great in his own right way, whether he occupied the office or not. I believe that his influence was exercised generally in favour of peace... May I also suggest, Sir, that the House might adjourn in memory of Marshal Stalin?

- Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru addressing the Parliament of India on 6 March 1953 on the occasion of Vladimir Stalin’s death.Parliamentary Debates, House of the People’, Official Report – Volume 1, No. 18, 6 March 1953, Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi

- In practice the Hindu is certainly not tolerant and is more narrow-minded than almost any person in any other country except the Jew.

- Nehru, 1953,letter to Home Minister Dr. Nailash Nath Katju. Quoted from Hinduism and Judaism compilation

- We have done no better thing than this [agreeing that Tibet belongs to China] since we became independent.

- Nehru to the Indian Parliament (1954). Quoted from Upadhya, S. (2015). Nepal and the geo-strategic rivalry between China and India. London : Routledge, 2015.

- I have become a queer mixture of the East and the West … Out of place everywhere, at home nowhere. Perhaps my thoughts and approach to life are more akin to what is called Western than Eastern, but India clings to me, as she does to all her children, in innumerable ways … I am a stranger and alien in the West. I cannot be of it. But in my own country also, sometimes I have an exile's feeling.

- As quoted in Ambassador's Report (1954) by Chester Bowles, p. 59

- Every little thing counts in a crisis and we want our weight felt and our voice heard in quarters which are for the avoidance of world conflict.

- Jawaharlal Nehru's Speeches 1949 - 1953 (1954), p. 144

- Theoretical approaches have their place and are, I suppose, essential but a theory must be tempered with reality.

- Jawaharlal Nehru's Speeches 1949 - 1953 (1954), p. 235

- Without peace, all other dreams vanish and are reduced to ashes.

- Address to the United Nations (28 August 1954); as quoted in The Macmillan Dictionary of Political Quotations (1993) by Lewis D. Eigen and Jonathan Paul Siegel, p. 698

- The only alternative to coexistence is codestruction.

- As quoted in The Observer [London] (29 August 1954)

- You know that I have had strong leanings towards Communism and have many friends among Communists.

- Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Second Series, Volume 8, p. 302

- Democracy and socialism are means to an end, not the end itself. We talk of the good of society. Is this something apart from, and transcending, the good of the individuals composing it? If the individual is ignored and sacrificed for what is considered the good of the society, is that the right objective to have?

It was agreed that the individual should not be sacrificed and indeed that real social progress will come only when opportunity is given to the individual to develop, provided "the individual" is not a selected group but comprises the whole community. The touchstone, therefore, should be how far any political or social theory enables the individual to rise above his petty self and thus think in terms of the good of all. The law of life should not be competition or acquisitiveness but cooperation, the good of each contributing to the good of all.- As quoted in World Marxist Review : Problems of Peace and Socialism (1958), p. 40

- You don't change the course of history by turning the faces of portraits to the wall.

- Statement to Nikita Khrushchev, as quoted in The New York Post (1 April 1959), and in The Cynic's Lexicon : A Dictionary of Amoral Advice (1984) by Jonathon Green, p. 184

- We talk about a secular state in India. It is perhaps not very easy even to find a good word in Hindi for "secular". Some people think it means something opposed to religion. That obviously is not correct. What it means is that it is state which honours all faiths equally and gives them equal opportunities; that, as a state, it does not allow itself to be attached to one faith or religion, which then becomes the state religion.

- Statement of 1961, as quoted in Locked Minds, Modern Myths (1997) by T. N. Madan

- Democracy is good. I say this because other systems are worse. So we are forced to accept democracy. It has good points and also bad. But merely saying that democracy will solve all problems is utterly wrong. Problems are solved by intelligence and hard work.

- As quoted in The New York Times (15 January 1961), and in Lifetime Speaker's Encyclopedia (1962) by Jacob Morton Braude, p. 173

- Culture is the widening of the mind and of the spirit. It is never a narrowing of the mind or a restriction of the human spirit or the country's spirit.

- The Quintessence of Nehru (1961) edited by K. T. Narasimhachar, p. 120

- Time is not measured by the passing of years but by what one does, what one feels, and what one achieves.

- As quoted in Al Arab Vol. 9 (1970) by the League of Arab States, p. 9

- America is a country no one should go to for the first time.

- As quoted in The Traveling Curmudgeon: Irreverent Notes, Quotes, and Anecdotes on Dismal Destinations, Excess Baggage, The Full Upright Position, and Other Reasons Not To Go There (2003) by Jon Winokur, p. 5

- We live in a wonderful world that is full of beauty, charm and adventure. There is no end to the adventures that we can have if only we seek them with our eyes open.

- As quoted in Building A Life Of Value : Timeless Wisdom to Inspire and Empower Us (2005) by Jason A. Merchey, p. 74

- The Bhagavad Gita deals essentially with the spiritual foundation of human existence. It is a call of action to meet the obligations and duties of life; yet keeping in view the spiritual nature and grander purpose of the universe.

- As quoted in A Tribute to Hinduism : Thoughts and Wisdom Spanning Continents and Time about India and Her Culture (2008) by Sushama Londhe, p. 191

- To be successful in life what you need is education.

- Quotations by 60 Greatest Indians. Dhirubhai Ambani Institute of Information and Communication Technology.

- The general Muslim outlook was thus one of Muslim nationalism or Muslim internationalism, and not of true nationalism. ... On the other hand, the Hindu idea of nationalism was definitely one of Hindu nationalism. It was not easy in this case (as it was in the case of the Muslims) to draw a sharp line between this Hindu nationalism and true nationalism. The two overlapped, as India is the only home of the Hindus and they form a majority there.

- Nehru, quoted in Religion, Caste, and Politics in India by C. Jaffrelot

- Every war waged by imperialist powers will be an imperialist war whatever the excuses put forward; therefore we must keep out of it.

- At the Lucknow session of the Congress in April 1936, in his presidential address. Quoted from Elst, Koenraad (2018). Why I killed the Mahatma: Uncovering Godse's defence. New Delhi : Rupa, 2018.

The Discovery of India (1946)

.jpeg)

War is the negation of truth and humanity. War may be unavoidable sometimes, but its progeny are terrible to contemplate. Not mere killing, for man must die, but the deliberate and persistent propagation of hatred and falsehood, which gradually become the normal habits of the people.

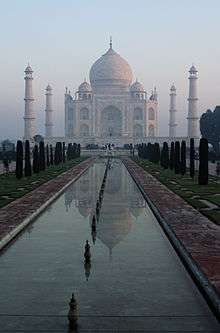

- The discovery of India — what have I discovered? It was presumptuous of me to imagine that I could unveil her and find out what she is today and what she was in the long past. Today she is four hundred million separate individual men and women, each differing from the other, each living in a private universe of thought and feeling. If this is so in the present, how much more so to grasp that multitudinous past of innumerable successions of human beings. Yet something has bound them together and binds them still. India is a geographical and economic entity, a cultural unity amidst diversity, a bundle of contradictions held together by strong but invisible threads. Overwhelmed again and again her spirit was never conquered, and today when she appears to be a plaything of a proud conqueror, she remains unsubdued and unconquered. About her there is the elusive quality of a legend of long ago; some enchantment seems to have held her mind. She is a myth and an idea, a dream and a vision, and yet very real and present and pervasive.

- The world of today has achieved much, but for all its declared love for humanity, it has based itself far more on hatred and violence than on the virtues that make one human. War is the negation of truth and humanity. War may be unavoidable sometimes, but its progeny are terrible to contemplate. Not mere killing, for man must die, but the deliberate and persistent propagation of hatred and falsehood, which gradually become the normal habits of the people. It is dangerous and harmful to be guided in our life's course by hatreds and aversions, for they are wasteful of energy and limit and twist the mind and prevent it from perceiving truth.

- History is almost always written by the victors and conquerors and gives their view. Or, at any rate, the victors' version is given prominence and holds the field.

- A study of Marx and Lenin produced a powerful effect on my mind and helped me to see history and current affairs in a new light. The long chain of history and of social development appeared to have some meaning, some sequence and the future lost some of its obscurity. The practical achievements of the Soviet Union were also tremendously impressive. Often I disliked or did not understand some development there and it seemed to me to be too closely concerned with the opportunism of the moment or the power politics of the day. But despite all these developments and possible distortions of the original passion for human betterment, I had no doubt that the Soviet Revolution bad advanced human society by a great leap and had lit a bright flame which could not be smothered, and that it had laid the foundation for the 'new civilisation' towards which the world would advance. I am too much of an individualist and believer in personal freedom to like overmuch regimentation. Yet it seemed to me obvious that in a complex social structure individual freedom had to be limited, and perhaps the only way to real personal freedom was through some such limitation in the social sphere. The lesser liberties may often need limitation in the interest of the larger freedom.

- We realized in our hearts that we could not do much till conditions were radically changed-hence our overwhelming desire for independence-and yet the passion for progress filled us and the wish to emulate other countries which had gone so far ahead in many ways. We thought of the United States of America and even of some eastern countries which were forging ahead. But most of all we had the example of the Soviet Union which in two brief decades, full of war and civil strife and in the face of what appeared to be insurmountable difficulties, had made tremendous progress. Some were attracted to communism, others were not, but all were fascinated by the advance of the Soviet Union in education and culture and medical care and physical fitness and in the solution of the problem of nationalities-by the amazing and prodigious effort to create a new world out of the dregs of the old.

A Tryst With Destiny (1947)

- Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance. It is fitting that at this solemn moment, we take the pledge of dedication to the service of India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity.

- In: Quicktime excerpt and in: Rediscovery of India, The: A New Subcontinent, Orient Blackswan, 1 January 1999, p. 191

- Excerpts from his speech delivered on the eve of declaration of Independence, on 14 August 1947, at the midnight hour declaring Independence of India on 15 August 1947.

- Freedom and power bring responsibility.

- The ambition of the greatest men of our generation has been to wipe every tear from every eye. That may be beyond us, but so long as there are tears and suffering, so long our work will not be over.

And so we have to labour and to work, and work hard, to give reality to our dreams. Those dreams are for India, but they are also for the world, for all the nations and peoples are too closely knit together today for any one of them to imagine that it can live apart. Peace has been said to be indivisible; so is freedom, so is prosperity now, and so also is disaster in this One World that can no longer be split into isolated fragments.

The Light Has Gone Out (1948)

- Speech after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi (30 January 1948) Full text online

The light has gone out, I said, and yet I was wrong. For the light that shone in this country was no ordinary light...

- Friends and Comrades, the light has gone out of our lives and there is darkness everywhere. I do not know what to tell you and how to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the Father of the Nation, is no more.

- The light has gone out, I said, and yet I was wrong. For the light that shone in this country was no ordinary light. The light that has illumined this country for these many years will illumine this country for many more years, and a thousand years later, that light will be seen in this country and the world will see it and it will give solace to innumerable hearts. For that light represented something more than the immediate past, it represented the living, the eternal truths, reminding us of the right path, drawing us from error, taking this ancient country to freedom.

- A great disaster is a symbol to us to remember all the big things of life and forget the small things of which we have thought too much. In his death he has reminded us of the big things of life, the living truth, and if we remember that, then it will be well with India.

The Unity of India (1948)

- In trying to analyse the various elements in the Congress, the dominating position of Gandhiji must always be remembered. He dominates to some extent the Congress, but far more so he dominates the masses. He does not easily fall in any group and is much bigger than the so-called Gandhian group. That is one of the basic factors of the situation. The conscious and thinking Leftists in the country recognise it and, whatever their ideological or temperamental differences with him, have tried to avoid anything approaching a split. Their attempt bas been to leave the Congress under its present leadership, which means under Gandhiji's guidance, and at the same time to push it as far as they could more to the left to radicalise it, and to spread own ideology."

- I had been considerably upset by the course of events in the Soviet Union, the trials and the repeated purges of vast numbers of Communists. I think the trials were generally bonafide and there bad been a definite conspiracy against the regime and widespread attempts at sabotage. Nevertheless, I could not reconcile myself to what was happening there, and it indicated to me ill-health in the body politic, which necessitated an ever-continuing use of violence and suppression. Still the progress made in Russian economy, the advancing standards of the people, the great advance in cultural matters and many other things continued to impress me. I was eager to visit the Soviet Union, but unfortunately my daughter's illness prevented me from going there.

- Whatever doubts I had about internal happenings in Russia, I was quite clear in my mind about her foreign policy. This had been consistently one of peace and, unlike England and France, of fulfilling international obligations and supporting the cause of democracy abroad. The Soviet Union stood as the one real effective bulwark against Fascism in Europe and Asia. Without the Soviet Union what could be the state of Europe today? Fascist reaction would triumph everywhere and democracy and freedom would become dreams of a past age.

Glimpses of World History (1949)

- Japan had come to terms with Russia because of her difficulties, but this did not mean approval of communism. Communism meant the end of emperor-worship, and feudalism and the exploitation of the masses by the ruling class, and indeed almost everything that the existing order stood for... But communism is the outcome of widespread misery due to social conditions, and unless these conditions are improved, mere repression can be no remedy. There is a terrible misery in Japan at present. The peasantry, as in China and India, are crushed under a tremendous burden of debt. Taxation, especially because of heavy military expenditure and war needs, is very heavy. Reports come of starving peasants trying to live on grass and roots, and of selling even their children. The middle classes are also in a bad way owing to unemployment and suicides have increased.

- The year you were born in - 1917 - was one of the memorable years of history.... In the very month you were born, Lenin started the great Revolution which has changed the face of Russia and Siberia.

- About his daughter Indira.

- Marx did not preach class conflict. He showed that in fact it existed, and had always existed in some form or other. His object in writing Capital was 'to lay bare the economic law of motion of modern society', and thus uncovering these fierce conflicts between different classes in society. These conflicts are not always obvious as class struggles, because the dominant class always tries to hide its own class character. But when the existing order is threatened, then it throws away all pretence and its real character appears, and there is open warfare between the classes. Forms of democracy and ordinary laws and procedures all disappear when this happens. Instead of these class struggles being due to misunderstanding or the villainy of agitators, as some people say, they are inherent in society, and they actually increase with better understanding of the conflict of interests.

- Russia today is a Soviet country, and its government is run by representatives of the workers and peasants. In some ways it it the most advanced country in the world. Whatever actual conditions may be, the whole structure of government and society is based on the principle of social equality.

- Apart from its effect on the war, the Revolution was in itself a tremendous event, unique in world history. Although it was the first revolution of its kind, it may not long remain the only one of its type, for it has become a challenge to other countries and an example for many revolutionaries all over the world... The March Revolution had been a spontaneous unorganized one, the November one had been carefully planned out. For the first time in history the representatives of the poorest classes, and especially of the industrial workers, were at the head of a country.

- There was no doubt or vagueness in Lenin's mind. His were the penetrating eyes which detected the moods of the masses; the clear head which could apply and adapt well-thought-out principles to changing situations; the inflexible will which held on to the course he had mapped out, regardless of immediate consequences... It is not many years since he died, and already Lenin has become a mighty tradition, not only in his native Russia, but in the world at large. As time passes he grows greater; he has become one of the chosen company of the world's immortals. Petrograd has become Leningrad, and almost every house in Russia has a Lenin corner or a Lenin picture. But he lives, not in monuments or pictures, but in the mighty work he did, and in the hearts of hundreds of millions of workers today who find inspiration in his example and the hope of a better day.

- What are the outstanding events, then, of these past fourteen years? First in importance, I think, and most striking of all, has been the rise and consolidation of the Soviet Union, the U.S.S.R. or the Union of Socialist and Soviet Republics, as it is called. I have told you already something of the enormous difficulties which Soviet Russia had to face in its fight for existence. That it won in spite of them is one of the wonders of this century. The Soviet system spread all over the Asiatic parts of the former Tsarist Empire, in Siberia right up to the Pacific and in Central Asia to within hail of the Indian frontier. Separate Soviet republics were formed, but they federated together into one Union, and this is now the U.S.S.R. This Union covers an enormous area in Europe and Asia, which is about one-sixth of the total land area of the world. The area is very big, but bigness by itself does not mean much, and Russia, and much more so Siberia and Central Asia, were very backward. The second wonder that the Soviets performed was to transform great parts of this area out of all recognition by prodigious schemes of planning. There is no instance in recorded history of such rapid advance of a people. Even the most backward areas in Central Asia have gone ahead with a rush which we in India might well envy.

- But the conflict has not ended and the fight between the two rival forces-capitalism and socialism-goes on. There can be no permanent compromise between the two although there have been, and there may be in the future, temporary arrangements and treaties between the two. Russia and communism stand at one pole, and the great capitalist countries of Western Europe and America stand at the other. Between the two, the liberals, the moderates, and the centre parties are disappearing everywhere.

- I have not included the Soviet Union in the above list of dictatorships, because the dictatorship there, although as ruthless as any other, is of a different type. It is not the dictatorship of an individual or a small group, but of a well-organised political party basing itself especially on the workers. They call it the 'dictatorship of the proletariat'.

- I have referred to democracy as 'formal' in the preceding paragraph. The communists say that it was not real democracy: it was only a democratic shell to hide the fact that one class ruled over the others. According to them democracy covered the dictatorship of the capitalist class. It was plutocracy, government by the wealthy. The much-paraded vote given to the masses gave them only the choice of saying once, in four. or five years, whether a certain person, X, might rule over them and exploit them or another person, Y, should do so. In either event the masses were to be exploited by the ruling class. Real democracy can only come when this class rule and exploitation end and only one class exists. To bring about this socialist State, however, a period of the dictatorship of the proletariat is necessary so as to keep down all capitalist and bourgeois elements in the population and prevent them from intriguing against the workers' State. In Russia this dictatorship is exercised by the Soviets in which all the workers and peasants and other 'active' elements are represented. Thus it becomes a dictatorship of the 90per cent over the remaining 10 or 5 per cent. That is the theory. In practice the Communist Party controls the Soviets and the ruling clique of communists controls the party. And the dictatorship is as strict, so far as censorship and freedom of thought or action are concerned, as any other. But as it is based on goodwill of the workers it must carry the workers with it. And, finally, there is no exploitation of the workers or any other class for the benefit of another. There is no exploiting class left. If there is any exploitation, it is done by the State for the benefit of all.

- Soviet policy with other nations was one of peace at almost any cost, for they wanted time to recuperate, and the great task of building up a huge country on socialistic lines absorbed their attention. There seemed to be no near prospect of social revolution in other countries, and so the idea of a 'world revolution' faded out for the time being. With Eastern countries Russia developed a policy of friendship and co-operation, although they were governed under the capitalist system.

- This Soviet solution of the minorities problem has interest for us, as we have to face a difficult minority problem ourselves. The Soviets' difficulties appear to have been far greater than ours, for they had 182 different nationalities to deal with. Their solution of the problem has been very successful. They went to the extreme length of recognizing each separate nationality and encouraging it to carry on its work and education in its own language. This was not merely to please the separatist tendencies of different minorities, but because it was felt that real education and cultural progress could take effect for the masses only if the native tongues were used. And the results achieved already have been remarkable.

- "In spite of this tendency to introduce lack of uniformity in the Union, the different parts are coming far nearer to each other than they ever did under the centralized government of the Tsars. The reason is that they have common ideals and they are all working together in a common enterprise. Each Union Republic has in theory the right to separate from the Union whenever it wants to, but there is little chance of its doing so, because of the great advantages of federation of socialist republics in the face of the hostility of the capitalist world…

- "These Central Asian republics have a special interest for us because of our age-old contact with Middle Asia. They are even more fascinating because of the remarkable progress they have made during the past few years. Under the Tsars they were very backward and superstitious countries with hardly any education and their women mostly behind the veil. Today they are ahead of India in many respects."

- This Five Year Plan had been drawn up after the most careful thought and investigation. The whole country had been surveyed by scientists and engineers, and numerous experts had discussed the problem of fitting in one part of the programme into another. For, the real difficulty came in this fitting in... But Russia had one great advantage over the capitalist countries. Under capitalism all these activities are left to individual initiative and chance, and owing to competition there is waste of effort. There is no co-ordination between different producers or different sets of workers, except the chance co-ordination which arises in the buyers and sellers coming to the same market... The Soviet Government had the advantage of controlling all the different industries and activities in the whole Union, and so it could draw up and try to work a single co-ordinated plan in which every activity found its proper place. There would be no waste in this, except such waste as might come from errors of calculation or working, and even such errors could be rectified far sooner with a unified control than otherwise.

- "For Russia, therefore, this building of heavy industries at a tremendous pace meant a very great sacrifice. All this construction, all this machinery that came from outside, had to be paid for, and paid for in gold and cash. How was this to be done? The people of the Soviet Union tightened their belts and starved and deprived themselves of even necessary articles so that payment could be made abroad. They sent their food-stuffs abroad, and with the price obtained for them paid for the machinery. They sent everything they could find a market for: wheat, rye, barley, corn, vegetables, fruits, eggs, butter, meat, fowls, honey, fish, caviare, sugar, oils, confectionery, etc. Sending these food articles outside meant that they themselves did without them. The Russian people had no butter, or very little of it, because it went abroad to pay for machinery. And so with many other goods...

- Nations have, in the past, concentrated all their efforts on the accomplishment of one great task, but this has been so in times of war only. During the World War, Germany and England and France lived for one purpose only - to win the war. To that purpose everything else was subordinated. Soviet Russia, for the first time in history, concentrated the whole strength of the nation in a peaceful effort to build, and not to destroy, to raise a backward country industrially and within a framework of socialism.

- But the privation, especially of the upper and middle-class peasantry, was very great, and often it seemed that the whole ambitious scheme would collapse, and perhaps carry the Soviet Government with it. It required immense courage to hold on. Many prominent Bolsheviks thought that the strain and suffering caused by the agricultural programme were too great and there should be a relaxation. But not so Stalin. Grin-fly and silently he held on. He was no talker, he hardly spoke in public. He seemed to be the iron image of an inevitable fate going ahead to the predestined goal. And something of his courage and determination spread among the members of the Communist Party and other workers in Russia.

- But, as I have told you, this Five Year Plan brought much suffering, and difficulties and dislocation. And people paid a terrible price willingly and accepted the sacrifices and sufferings for a few years in the hope of a better time afterwards; some paid the price unwillingly and only because of the compulsion of the Soviet Government. Among those who suffered most were the kulaks or richer peasants. With their great wealth and special influence, they did not fit into the new scheme of things. They were capitalistic elements which prevented the collective farms from developing on socialist lines. Often they opposed this collectivization, sometimes they entered the collectives to weaken them from inside or to make undue personal profit out of them. The Soviet Government came down heavily on them. The Government was also very hard on many middle-class people whom it suspected of espionage and sabotage on behalf of its enemies. Because of this, large numbers of engineers were punished and sent to gaol.

- The tremendous growth of the Soviet Union was in itself a remarkable sign of prosperity. It was not due, as in America, to immigration from outside. It showed that in spite of the privations and hardships of the people there was, as a general rule, no actual starvation. A severe system of rationing managed to supply the absolutely necessary articles of food to the population. Competent observers tell us that this rapid growth of population is largely due to a feeling of economic security among the people.

- Work remains, and must remain, though in the future it is likely to be pleasanter and lighter than in the trying early years of planning. Indeed, the maxim of the Soviet Union is: 'He that will not work, neither shall he eat.' But the Bolsheviks have added a new motive for work: the motive to work for social betterment. In the past, idealists and stray individuals have been moved to activity by this incentive, but there is no previous instance of society as a whole accepting and reacting to this motive. The very basis of capitalism was competition and individual profit, always at the expense of others. This profit motive is giving place to the social motive in the Soviet Union and, as an American writer says, workers in Russia are learning that, 'from the acceptance of mutual dependence comes independence from want or fear'. This elimination of the terrible fear of poverty and insecurity, which bears down upon the masses everywhere, is a great achievement. It is said that this relief has almost put an end to mental diseases in the Soviet Union.

- I shall tell you just a few odd facts which might interest you. The educational system in Russia is supposed by many competent judges to be the best and most up-to-date in existence.

- The old palaces of the Tsars and the nobility have now become museums and rest-houses and sanatoria for the people... I suppose the old palaces now serve the purpose of children and young people. Children and the young are the favoured persons in Soviet land today, and they get the best of everything, even though others might suffer lack. It is for them that the present generation labours, for it is they who will inherit the socialised and scientific State, if that finally comes into existence in their time.

- Soviet Russia has been behaving internationally very much as a satisfied Power, avoiding all trouble, and trying to keep peace at all costs. This is the opposite of a revolutionary policy which would aim at fomenting revolution in other countries. It is a national policy of building up socialism in a single country and avoiding all complications outside. Necessarily, this results in compromises with imperialist and capitalist Powers. But the essential socialist basis of Soviet economy continues, and the success of this is itself the most powerful argument in favour of socialism.

- The conflict between capitalism and democracy is inherent and continuous; it is often hidden by misleading propaganda and by the outward forms of democracy, such as parliaments, and the sops that the owning classes throw to the other classes to keep them more or less contented. A time comes when there are no more sops left to be thrown, and then the conflict between the two groups comes to a head, for now the struggle is for the real thing, economic power in the State. When that stage comes, all the supporters of capitalism, who had so far played with different parties, band themselves together to face the danger to their vested interests. Liberals and such-like groups disappear, and the forms of democracy are put aside. This stage bas now arrived in Europe and America, and fascism, which is dominant in some form or other in mast countries, represents that stage. Labour is everywhere on the defensive, not strong enough to face this new and powerful consolidation of the forces of capitalism. And yet, strangely enough, the capitalist system itself totters and cannot adjust itself to the new world. It seems certain that even if it succeeds in surviving, it will be but another stage in the long conflict. For modern industry and modern life itself, under any form of capitalism, are battlefields where armies are continually clashing against each other.

- The Soviet Union in Europe and Asia stands today a continuing challenge to the tottering capitalism of the western world. While trade depression and slump and unemployment and repeated crises paralyse capitalism, and the old order gasps for breath, the Soviet Union is a land full of hope and energy and enthusiasm, feverishly building away and establishing the socialist order. And this abounding youth and life, and the success the Soviet Union has already achieved, are impressing and attracting thinking people all over the world.

- Great progress was made and the standards of life went up, and are continually going up. Culturally and educationally, and in many other ways, the advance all over the Soviet Union has been remarkable. Anxious to continue this advance and to consolidate its socialist economy, Russia consistently followed a peace policy in international affairs. In the League of Nations it stood for substantial disarmament, collective security, and corporate action against aggression. It tried to accommodate itself to the capitalist Great Powers and, in consequence, Communist Parties sought to build up 'popular fronts' or 'joint fronts' with other progressive parties.

- In spite of this general progress and development, the Soviet Union passed throught a severe internal crisis during this period... It is difficult for me to express a definite opinion about these trials or the events that led up to them, as the facts are complicated and not clear. But it is undoubted that the trials disturbed large numbers of people, including many friends of Russia, and added to the prejudice against the Soviet Union. Close observers are of opinion that there was a big conspiracy against the Stalinist regime and that the trials were bonafide. It also seems to be established that there was no mass support behind the conspiracy, and that the reaction of the people was definitely against the opponents of Stalin. Nevertheless, the extent of the repression, which may have hit many innocent persons also, was a sign of ill-health, and injured the Soviet's position internationally.

- The people inhabiting it [Palestine] are predominantly Muslim Arabs, and they demand freedom and unity with their fellow-Arabs of Syria. But the British policy has created a special minority problem here – that of the Jews – and the Jews side with the British and oppose the freedom of Palestine, as they fear that would mean Arab rule.....On the Arab side are numbers, on the other side great financial resources and the world-wide organization of Jewry...... The Jews are a very remarkable people. Originally they were a small tribe, or several tribes, in Palestine, and their early story is told in the old Testament of the Bible. Rather conceited they were, thinking of themselves as the Chosen People, But this is a conceit in which nearly all people have indulged...... They [British] declared it was their intention to establish a “Jewish National Home” in Palestine. This declaration was made to win the good will of international Jewry, and this was important from the money point of view. It was welcomed by most Jews.

- But there was one little drawback, one not unimportant fact seems to have been overlooked. Palestine was not a wilderness, or an empty, uninhabited place. It was already somebody else’s home. So that this generous gesture of the British Government was really at the expense of the people who already lived in Palestine, and these people, including Arabs, non- Arabs, Muslims, Christians, and , in fact, everybody who was not a Jew, protested vigorously at the declaration...... The Jewish population is already nearly a quarter of the Muslim population, and their economic power is far greater. They seem to look forward to the day when they will be the dominant community in Palestine. The Arabs tried to gain their co-operation in the struggle for national freedom and democratic government, but they rejected these advances. They have preferred to take sides with the foreign ruling Power, and have thus helped it to keep back freedom from the majority of the people. It is not surprising that this majority, comprising the Arabs, chiefly, and also the Christians, bitterly resent this attitude of the Jews.

Soviet Russia: Some Random Sketches and Impressions (1949)

- [Russia is] a country which has many points of contact with ours and which has launched one of the mightiest experiments in history. All the world is watching her, some with fear and hatred, and others with passionate hope and longing to follow in her path." Then identifying himself with the second group, he theorises. "Much depends on the prejudices and preconceived notions which he brings to his task. But whichever view may be right, no one can deny the fascination of this strange Eurasian country of the hammer and sickle, where workers and peasants sit on the thrones of the mighty and upset the best-laid schemes of mice and men.

- For us in India the fascination is even greater, and even .our self-interest compels us to understand the vast forces which have upset the old order of things and brought a new world into existence, where values have changed utterly and old standards have given place to new. We are a conservative people, not ever-fond of change, always trying to forget our present misery and degradation in vague fancies of our glorious past and immortal civilisation. But the past is dead and gone and our immortal civilisation does not help us greatly in solving the problems of today.

- Russia thus interests us because it may help us to find some solution for the great problems which face the world today. It interests us specially because conditions there have not been, and are not even now, very dissimilar to conditions in India. Both are vast agricultural countries with only the beginnings of industrialisation, and both have to face poverty and illiteracy. If Russia finds a satisfactory solution for these, our work in India is made easier.

- It is right therefore that India should be eager to learn more about Russia. So far her information has been largely derived from subsidised news agencies inimical to Russia, and the most fantastic stories about her have been circulated.

- He (Lenin) lies asleep as it were and it is difficult to believe that he is dead. In life they say he was not beautiful to look at. He had too much of common clay in him and about him was the 'smell of the Russian soil'. But in death there is a strange beauty and his brow is peaceful and unclouded. On his lips there hovers a smile and there is a suggestion of pugnacity, of work done and success achieved. He has a uniform on and one of his hands is lightly clenched. Even in death he is the dictator. In India, he would certainly have been canonised, but saints are not held in repute in Soviet circles, and the people of Russia have done him the higher honour of loving him as one of themselves.

- It is difficult for most of us to think of our ideals and our theories in terms of reality. We have talked and written of Swaraj for years, but when Swaraj comes it will probably take us by surprise. We have passed the independence resolution at the Congress, and yet how many of us realise its full implications? How many belie it by their words and actions? For them it is something to be considered as a distant goal, not as a thing of today or tomorrow. They talk of Swaraj and independence in their councils but their minds are full of reservations and their acts are feeble and halting.

- Nothing is perhaps more confusing to the student of Russia than the conflicting reports that come of the treatment of prisoners and of the criminal law. We are told of the Red Terror and ghastly and horrible details are provided for our consumption; we are also told that the Russian prison is an ideal residence where anyone can live in comfort and ease and with a minimum of restraint. Our own visit to the chief prison in Moscow created a most favourable impression on our minds.

- As we were very much pressed for time we were unable to see as much of the jail as we wanted to. We had an impression that we had been shown the brighter side of jail life. Nonetheless, two facts stood out. One was that we had actually seen desirable and radical improvements over the old system prevailing even now in most countries and the second and even more important fact was the mentality of the prison officials, and presumably the higher officials of the government also, in regard to jails. Actual conditions may or may not be good but the general principles laid down for jails are certainly far in advance of anything we had known elsewhere in practice. Anyone with a knowledge of prisons in India and of the barbarous way in which handcuffs, fetters and other punishments are used will appreciate the difference. The governor of the prison in Moscow who took us round was all the time laying stress on the human side of jail life, and how it was their endeavour to keep this in the front and not to make the prisoner feel in any way dehumanised or outcasted. I wish we in India would remember this wholesome principle and practise it in our daily lives even outside jail.... It can be said without a shadow of doubt that to be in a Russian prison is far more preferable than to be a worker in an Indian factory, whose lot is 10 to 11 hours work a day and then to live in a crowded and dark and airless tenement, hardly fit for an animal. The mere fact that there are some prisons like the ones we saw is in itself something for the Soviet Government to be proud of.

- I remember attending a banquet given by the scientists and professors in Moscow. There were people from many countries present and speeches in a variety of languages were made. I remember specially a speech given by a young student who had come from far off Uruguay in South America .... He spoke in the beautiful sonorous periods of the Spanish language and he told us that he was going back to his distant country with the red star of Soviet Russia engraved in his heart and carrying the message of social freedom to his young comrades in Uruguay. Such was the reaction of Soviet Russia on his young and generous heart. And yet there are many who tell us that Russia is a land of anarchy and misery and the Bolsheviks are assassins and murderers who have cast themselves outside the pale of human society.

- But to understand the great drama of the Russian Revolution and the inner forces that shaped and brought the great change about, a study of cold theory is of little use. The October Revolution was undoubtedly one of the great events of world history, the greatest since the first French Revolution, and its story is more absorbing, from the human and the dramatic point of view, than any We or phantasy.

Speech to the US Congress (13 October 1949)

Where freedom is menaced or justice threatened or where aggression takes place, we cannot be and shall not be neutral.

- Where freedom is menaced or justice threatened or where aggression takes place, we cannot be and shall not be neutral.

- We have achieved political freedom but our revolution is not yet complete and is still in progress, for political freedom without the assurance of the right to live and to pursue happiness, which economic progress alone can bring, can never satisfy a people. Therefore, our immediate task is to raise the living standards of our people, to remove all that comes in the way of the economic growth of the nation. We have tackled the major problem of India, as it is today the major problem of Asia, the agrarian problem. Much that was feudal in our system of land tenure is being changed so that the fruits of cultivation should go to the tiller of the soil and that he may be secure in the possession of the land he cultivates. In a country of which agriculture is still the principal industry, this reform is essential not only for the well-being and contentment of the individual but also for the stability of society. One of the main causes of social instability in many parts of the world, more especially in Asia, is agrarian discontent due to the continuance of systems of land tenure which are completely out of place in the modem world. Another — and one which is also true of the greater part of Asia and Africa — is the low standard of living of the masses.

- India is industrially more developed than many less fortunate countries and is reckoned as the seventh or eighth among the world's industrial nations. But this arithmetical distinction cannot conceal the poverty of the great majority of our people. To remove this poverty by greater production, more equitable distribution, better education and better health, is the paramount need and the most pressing task before us and we are determined to accomplish this task. We realize that self-help is the first condition of success for a nation, no less than for an individual. We are conscious that ours must be the primary effort and we shall seek succour from none to escape from any part of our own responsibility. But though our economic potential is great, its conversion into finished wealth will need much mechanical and technological aid. We shall, therefore, gladly welcome such aid and co-operation on terms that are of mutual benefit. We believe that this may well help in the solution of the larger problems that confront the world. But we do not seek any material advantage in exchange for any part of our hard-won freedom.

Autobiography (1936; 1949; 1958)

Religion merges into mysticism and metaphysics and philosophy. There have been great mystics, attractive figures, who cannot easily be disposed of as self-deluded fools.

- Several editions of Nehru's autobiography were published in his lifetime, including An Autobiography (1936), Jawaharlal Nehru, An Autobiography, with Musings on Recent Events in India (1949), and Toward Freedom : The Autobiography of Jawaharlal Nehru (1958) Some passages occur in all of these, but with slight variations of wording.

_in_Amritsar%2C_India.jpg)

India is supposed to be a religious country above everything else, and Hindu and Muslim and Sikh and others take pride in their faiths and testify to their truth by breaking heads.

A leader or a man of action in a crisis almost always acts subconsciously and then thinks of the reasons for his action.

To be in good moral condition requires at least as much training as to be in good physical condition. But that certainly does not mean asceticism or self-mortification.

Whether we believe in God or not, it is impossible not to believe in something, whether we call it a creative life-giving force, or vital energy inherent in matter which gives it its capacity for self-movement and change and growth, or by some other name, something that is as real, though elusive, as life is real when contrasted with death.

- My intention was to trace, as far as I could, my own mental development and not write a survey of recent Indian history.

- My thoughts travelled more to other countries, and I watched and studied, as far as I could in goal, the world situation in the grip of the great depression. I lead as many books as I could find on the subject, and the more I read the more fascinated I grew. India with her problems and struggles became just a part of this mighty world drama, of the great struggle of political and economic forces that was going on everywhere, nationally and internationally. In that struggle my own sympathies went increasingly towards the communist side.

- I had long been drawn to socialism and communism, and Russia had appealed to me. Much in Soviet Russia I dislike - the ruthless suppression of all contrary opinion, the wholesale regimentation, the unnecessary violence (as I thought) in carrying out various policies. But there was no lack of violence and suppression in the capitalist world, and I realised more and more bow the very basis and foundation of our acquisitive society and property was violence. Without violence it could not continue for many days. A measure of political liberty meant little indeed when the fear of starvation was always compelling the vast majority of people everywhere to submit to the will of the few, to the greater glory and advantage of the latter.

- Violence was common in both places, but the violence of the capitalist order seemed inherent in it; whilst the violence of Russia, bad though it was, aimed at a new order based on peace and cooperation and real freedom for the masses. With all her blunders, Soviet Russia had triumphed over enormous difficulties and taken great strides towards this new order. While the rest of the world was in the grip of the depression and going backward in some ways, in the Soviet country a great new world was being built up before our eyes. Russia, following the great Lenin, looked into the future and thought only of what was to be, while other countries lay numbed under the dead hand of the past and spent their energy in preserving the useless relics of a bygone age. In particular, I was impressed by the reports of the great progress made by the backward regions of Central Asia under the Soviet regime. In the balance, therefore, I was all in favour of Russia, and the presence and example of the Soviets was a bright and heartening phenomenon in a dark and dismal world.

- But Soviet Russia's success or failure, vastly important as it was as a practical experiment in establishing a communist state, did not affect the soundness of the theory of communism. The Bolsheviks may blunder or even fail because of national or international reasons and yet the communist theory may be correct. On the basis of that very theory it was absurd to copy blindly what had taken place in Russia, for its application depended on the particular conditions prevailing in the country in question and the stage of its historical development. Besides, India, or any other country, could profit by the triumphs as well as the inevitable mistakes of the Bolsheviks. Perhaps the Bolsheviks had tried to go too fast because, surrounded as they were by a world of enemies, they feared external aggression. A slower tempo might avoid much of the misery caused in the rural areas. But then the question arose if really radical results could be obtained by slowing down the rate of change. Reformism was an impossible solution of any vital problem at a critical moment when the basic structure had to be changed, and however slow the progress might be later on, the initial step must be a complete break with the existing order, which had fulfilled its purpose and was now only a drag on future progress.

- Russia apart, the theory and philosophy of Marxism lightened up many a dark corner of my mind. History came to have a new meaning for me. The Marxist interpretation threw a flood of light on it, and it became an unfolding drama with some order and purpose, howsoever unconscious, behind it. In spite of the appalling waste and misery of the past and the present, the future was bright with hope, though many dangers intervened. It was the essential freedom from dogma and the scientific outlook of Marxism that appealed to me. It was true that there was plenty of dogma in official communism in Russia and elsewhere, and frequently heresy hunts were organised, That seemed to be deplorable, though it was not difficult to understand in view of the tremendous changes taking place rapidly in the Soviet countries when effective opposition might have resulted in catastrophic failure. The great world crisis and slump seemed to justify the Marxist analysis. While all other systems and theories were groping about in the dark, Marxism alone explained it more or less satisfactorily and offered a real solution.

- As this conviction grew upon me, I was filled with a new excitement and my depression at the non-success of civil disobedience grew much less. Was not the world marching rapidly towards the desired consummation? There were grave dangers of wars and catastrophes, but at any rate we were moving. There was no stagnation. Our national struggle became a stage in the longer journey, and it was as well that repression and suffering were tempering our people for future struggles and forcing them to consider the new ideas that were stirring the world. We would be the stronger and the more disciplined and hardened by the elimination of the weaker elements. Time was in our favour.

- As between fascism and communism my sympathies are entirely with communism. As these pages will show, I am very far from being a communist. My roots are still perhaps partly in the nineteenth century, and I have been too much influenced by the humanist liberal tradition to get out of it completely. This bourgeois background follows me about and is naturally a source of irritation to many communists. I dislike dogmatism, and the treatment of Karl Marx's writings or any other book as revealed scripture which cannot be challenged, and the regimentation and heresy hunts which seem to be a feature of modern communism. I dislike also much that has happened in Russia, and especially the excessive use of violence in normal times. But still I incline more and more towards a communist philosophy.

- Religion merges into mysticism and metaphysics and philosophy. There have been great mystics, attractive figures, who cannot easily be disposed of as self-deluded fools. Yet, mysticism (in the narrow sense of the word) irritates me; it appears to be vague and soft and flabby, not a rigorous discipline of the mind but a surrender of mental faculties and living in a sea of emotional experience. The experience may lead occasionally to some insight into inner and less obvious processes, but it is also likely to lead to self-delusion.

- For the first time I began to think, consciously and deliberately of religion and other worlds. The Hindu religion especially went up in my estimation; not the ritual or ceremonial part, but it's great books, the "Upnishads", and the "Bhagavad Gita".

- Jawaharlal Nehru, an autobiography, p. 15

- Essentially I am interested in this world, in this life, not in some other world or future life. Whether there is such a thing as soul, or whether there is survival after death or not, I do not know; and important as these questions are, they do not trouble me the least.

- Marx may be wrong in some of his statements, or his theory of value; this I am not competent to judge. But he seems to me to have possessed quite an extraordinary degree of insight into social phenomena, and this insight was apparently due to the scientific method he adopted. This method, applied to past history as well as current events, helps us in understanding them far more than any other method of apporach, and it is because of this that the most revealing and keen analysis of the changes that are taking place in the world today come from Marxist writers. It is easy to point out that Marx ignored or underrated certain subsequent tendencies, like the rise of a revolutionary element in the middle class, which is so notable today. But the whole value of Marxism seems to me to lie in its absence of dogmatism, in its stress on a certain outlook and mode of approach, and in its attitude to action. That outlook helps us in understanding the social phenomena of our own times, and points out the way of action and escape.

- It is difficult to be patient with many communists; they have developed a peculiar method of irritating others. But they are a sorely tried people, and, outside the Soviet Union, they have to contend against enormous difficulties. I have always admitted their great courage and capacity for sacrifice. They suffer greatly, as unhappily untold millions suffer in various ways, but not blindly before a malign and all-powerful fate. They suffer as human beings, and there is a tragic nobility about such suffering.

- What the mysterious is I do not know. I do not call it God because God has come to mean much that I do not believe in. I find myself incapable of thinking of a deity or of any unknown supreme power in anthropomorphic terms, and the fact that many people think so is continually a source of surprise to me. Any idea of a personal God seems very odd to me.

Intellectually, I can appreciate to some extent the conception of monism, and I have been attracted towards the Advaita (non-dualist) philosophy of the Vedanta, though I do not presume to understand it in all its depth and intricacy, and I realise that merely an intellectual appreciation of such matters does not carry one far. - Many a Congressman was a communalist under his national cloak. But the Congress leadership stood firm and, on the whole, refused to side with either communal party, or rather with any communal group. Long ago, right at the commencement of non-co-operation or even earlier, Gandhiji had laid down his formula for solving the communal problem. According to him, it could only be solved by goodwill and the generosity of the majority group, and so he was prepared to agree to everything that the Muslims might demand. He wanted to win them over, not to bargain with them. With foresight and a true sense of values he grasped at the reality that was worthwhile; but others who thought they knew the market price of everything, and were ignorant of the true value of anything, stuck to the methods of the market-place. They saw the cost of purchase with painful clearness, but they had no appreciation of the worth of the article they might have bought.

- I turned inevitably with goodwill towards communism, for, whatever its faults, it was at least not hypocritical and not imperialistic. It was not a doctrinal adherence, as I did not know much about the fine points of Communism, my acquaintance being limited at the time to its broad features. There attracted me, as also the tremendous changes taking place in Russia. But Communists often irritated me by their dictatorial ways, their aggressive and rather vulgar methods, their habit of denouncing everybody who did not agree with them. This reaction was no doubt due, as they would say, to my own bourgeois education and up-bringing.

- Russia apart, the theory and philosophy of Marxism lightened up many a dark corner of my mind. History came to have a new meaning for me. The Marxist interpretation threw a flood of light on it... It was the essential freedom from dogma and the scientific outlook of Marxism that appealed to me.

- India is supposed to be a religious country above everything else, and Hindu and Muslim and Sikh and others take pride in their faiths and testify to their truth by breaking heads. The spectacle of what is called religion, or at any rate organised religion, in India and elsewhere has filled me with horror, and I have frequently condemned it and wished to make a clean sweep of it. Almost always it seems to stand for blind belief and reaction, dogma and bigotry, superstition and exploitation, and the preservation of vested interests. And yet I knew well that there was something else in it, something which supplied a deep inner craving of human beings. How else could it have been the tremendous power it has been and brought peace and comfort to innumerable tortured souls? Was that peace merely the shelter of blind belief and absence of questioning, the calm that comes from being safe in harbour, protected from the storms of the open sea, or was it something more? In some cases certainly it was something more.

But organized religion, whatever its past may have been, today is largely an empty form devoid of real content. Mr. G. K. Chesterton has compared it (not his own particular brand of religion, but other!) to a fossil which is the form of an animal or organism from which all its own organic substance has entirely disappeared, but has kept its shape, because it has been filled up by some totally different substance. And, even where something of value still remains, it is enveloped by other and harmful contents. That seems to have happened in our Eastern religions as well as in the Western.

- Because of this wide and comprehensive outlook, the real understanding communist develops to some extent an organic sense of social life. Politics for him cease to be a mere record of opportunism or a groping in the dark. The ideals and objectives he works forgive a meaning to the struggle and to the sacrifices be willingly faces. He feels that he is part of a grand army marching forward to realise human fate and destiny, and he has the sense of 'marching step by step with history'. Probably most communists are far from feeling all this. Perhaps only Lenin had this organic sense of life in its fullness which made his action so effective. But to a small extent every communist, who has understood the philosophy of his movement, has it.

- I knew that Gandhiji usually acts on instinct (I prefer to call it that than the "inner voice" or an answer to prayer) and very often that instinct is right. He has repeatedly shown what a wonderful knack he has of sensing the mass mind and of acting at the psychological moment. The reasons which he afterward adduces to justify his action are usually afterthoughts and seldom carry one very far. A leader or a man of action in a crisis almost always acts subconsciously and then thinks of the reasons for his action.

- Action to be effective must be directed to clearly conceived ends. Life is not all logic, and those ends will have to be varied from time to time to fit in with it, but some end must always be clearly envisaged.

- To be in good moral condition requires at least as much training as to be in good physical condition. But that certainly does not mean asceticism or self-mortification. Nor do I appreciate in the least the idealization of the "simple peasant life." I have almost a horror of it, and instead of submitting to it myself I want to drag out even the peasantry from it, not to urbanization, but to the spread of urban cultural facilities to rural areas.

- In this matter, as in many others, my sympathies were with the Left.

- Organised religion allying itself to theology and often more concerned with its vested interests than with the things of the spirit encourages a temper which is the very opposite of science. It produces narrowness and intolerance, credulity and superstition, emotionalism and irrationalism. It tends to close and limit the mind of man and to produce a temper of a dependent, unfree person.