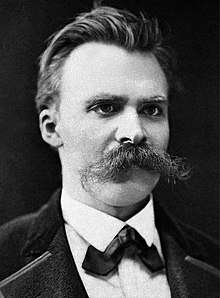

Philistines … devised the notion of an epigone-age in order to secure peace for themselves, and to be able to reject all the efforts of disturbing innovators summarily as the work of epigones. With the view of ensuring their own tranquility, these smug ones even appropriated history, and sought to transform all sciences that threatened to disturb their wretched ease into branches of history. ~ Friedrich Nietzsche

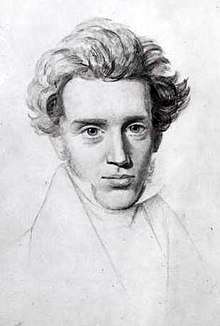

It goes against the grain for me to do what so often happens, to speak inhumanly about the great as if a few millennia were an immense distance. I prefer to speak humanly about it, as if it happened yesterday, and let only the greatness itself be the distance. ~ Søren Kierkegaard

Historicism is a mode of thinking that assigns a central and basic significance to a specific context, such as historical period, geographical place and local culture.

Quotes

- Die Natur dieser Traurigkeit wird deutlicher, wenn man die Frage aufwirft, in wen sich denn der Geschichtsschreiber des Historismus eigentlich einfühlt. Die Antwort lautet unweigerlich in den Sieger. Die jeweils Herrschenden sind aber die Erben aller, die je gesiegt haben. Die Einfühlung in den Sieger kommt demnach den jeweils Herrschenden allemal zugut.

- The nature of this melancholy becomes clearer, once one asks the question, with whom does the historical writer of historicism actually empathize. The answer is irrefutably with the victor. Those who currently rule are however the heirs of all those who have ever been victorious. Empathy with the victors thus comes to benefit the current rulers every time.

- Walter Benjamin (1940) Theses on the Philosophy of History, VII #7 (1940; first published, in German, 1950, in English, 1955).

- The nature of this melancholy becomes clearer, once one asks the question, with whom does the historical writer of historicism actually empathize. The answer is irrefutably with the victor. Those who currently rule are however the heirs of all those who have ever been victorious. Empathy with the victors thus comes to benefit the current rulers every time.

- Historicism runs counter to the specific capacity of the literary work to escape the limits of historical time, to allow for the cross-generational flourishing of tradition, and open the present to a multidimensional temporality.

- Russell Berman, Fiction Sets You Free: Literature, Liberty and Western Culture (2007), p. 20.

- Historicism and cultural relativism actually are a means to avoid testing our own prejudices and asking, for example, whether men are really equal or whether that opinion is merely a democratic prejudice.

- Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind (New York: 1988), p. 40.

- There are two kinds of openness, the openness of indifference—promoted with the twin purposes of humbling our intellectual pride and letting us be whatever we want to be, just as long as we don’t want to be knowers—and the openness that invites us to the quest for knowledge and certitude, for which history and the various cultures provide a brilliant array of examples for examination. This second kind of openness encourages the desire that animates and makes interesting every serious student—”I want to know what is good for me, what will make me happy”—while the former stunts that desire. Openness, as currently conceived, is a way of making surrender to whatever is most powerful, or worship of vulgar success, look principled. It is historicism’s ruse to remove all resistance to history, which in our day means public opinion, a day when public opinion already rules.

- Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind (New York: 1988), p. 41.

- At every turn, the struggle for equality was resisted by many of the powerful. And some have said we should not judge their failures by the standards of a later time, yet in every time there were men and women who clearly saw this sin and called it by name.

- George W. Bush, Hope and Conscience Will Not Be Silenced (8 July 2003)

- Hayek ripped G. W. F. Hegel in The Counter-Revolution of Science’s third part for his “historicism”—the idea, in Hayek’s terminology, that history moves in set and predictable stages. He considered this idea fatally flawed and societies that were based on it to be unsuccessful, unproductive, and unfree.

Historicism denies free will. The future is what we make of it.- Alan Ebenstein, Hayek's Journey: The Mind of Friedrich Hayek (2003), Ch. 8. “The Abuse and Decline of Knowledge”

- History, however, is not a linear narrative of progress. Rights may be won and taken away; gains are never complete or uncontested, and popular movements generate their own countervailing pressures.

- Eric Foner, "The Century: A Nation's-Eye View" (10 December 2002), The Nation

- Just as the works of Apelles and Sophocles, if Raphael and Shakespeare had known them, should not have appeared to them as mere preliminary exercises for their own work, but rather as a kindred force of the spirit, so, too reason cannot find in its own earlier forms mere useful preliminary exercises for itself.

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Difference of the Fichtean and Schellingean System of Philosophy, in W. Kaufmann, Hegel (1966), p. 49

- It goes against the grain for me to do what so often happens, to speak inhumanly about the great as if a few millennia were an immense distance. I prefer to speak humanly about it, as if it happened yesterday, and let only the greatness itself be the distance.

- Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling (1843), S. Walsh, trans. (2006), p. 28

- How can historicism consistently exempt itself from its own verdict that all human thought is historical?

- Laurence Lampert (1997) Leo Strauss and Nietzsche, p. 6.

- The past, when it is merely known historically (that is, as a subject for abstract study), somehow piles itself up outside our real lives. ... I think that one of the duties of a philosopher, if he shows himself worthy of his vocation today, is to attack quite directly those dissimulating forces which are all working toward what might be called the neutralization of the past; and whose conjoint effect consists in arousing in contemporary man a feeling of what I should like to call insulation in time.

- Gabriel Marcel, Man Against Mass Society (1952), p. 39

- Interpretations of the past are subject to change in response to new evidence, new questions asked of the evidence, new perspectives gained by the passage of time. [...] The unending quest of historians for understanding the past — that is, "revisionism" — is what makes history vital and meaningful.

- James M. McPherson, "Revisionist Historians" (September 2003), Perspectives, American Historical Association

- Ignorance of the phenomenon of esoteric writing may even cause us to misunderstand the whole character of human thought as such, especially in its relation to politics or society. For, through the practice of esotericism, the great minds of the past endeavored to create the impression that they were supporters of the conventional political and religious views of their age. They used all their genius, in effect, to convince their (non-esoteric) readers that even their highest philosophical reflections always remained captive of the prevailing order. Thus, if one surveys the record of past philosophical writing without awareness of its esoteric character, one will necessarily and systematically misconstrue the relation of human thought to politics—or of reason to history, theory to practice—seeing every mind as merely the prisoner of its times. The result will be what in fact we see everywhere in the recent explosion of hermeneutical theory: the radical politicization or historicization of thought.

- Arthur Melzer, “On the Pedagogical Motive for Esoteric Writing,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 69, Issue 4, November 2007, pp. 1015-1016.

- [Philistines] only devised the notion of an epigone-age in order to secure peace for themselves, and to be able to reject all the efforts of disturbing innovators summarily as the work of epigones. With the view of ensuring their own tranquility, these smug ones even appropriated history, and sought to transform all sciences that threatened to disturb their wretched ease into branches of history... No, in their desire to acquire an historical grasp of everything, stultification became the sole aim of these philosophical admirers of “nil admirari.” While professing to hate every form of fanaticism and intolerance, what they really hated, at bottom, was the dominating genius and the tyranny of the real claims of culture.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations (A. Ludovici trans.), “David Strauss,” § 1.2.

- I do not know what meaning classical studies could have for our time if they were not untimely—that is to say, acting counter to our time and thereby acting on our time and, let us hope, for the benefit of a time to come.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations, “On the uses and disadvantages of history for life,” Preface, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), § 2.0, p. 60.

- The junk-bond era has also spawned something that calls itself New Historicism. This seems to be a refuge for English majors without critical talent or broad learning in history or political science. [...] To practice it, you must apparently lack all historical sense.

- Camille Paglia (1991) Junk Bonds and Corporate Raiders : Academe in the Hour of the Wolf. p. 223.

- If we are uncritical we shall always find what we want: we shall look for, and find, confirmations, and we shall look away from, and not see, whatever might be dangerous to our pet theories. In this way it is only too easy to obtain what appears to be overwhelming evidence in favor of a theory which, if approached critically, would have been refuted.

- Karl Popper (1957) The Poverty of Historicism. Ch. 29 The Unity of Method.

- The negations of post-structuralism and of certain varieties of deconstruction are precisely as dogmatic, as political as were the positivist equations of archival historicism. The "emptiness of meaning" postulate is no less a priori, no less a case of despotic reductionism than were, say, the axioms of economic and psycho-sociological causality in regard to the generation of meaning in literature and the arts in turn-of-the-century pragmatism and scientism.

- George Steiner (1989) Real Presences. p. 174-175.

- History teaches us that a given view has been abandoned in favor of another by all men, or by all competent men, or perhaps by only the most vocal men; it does not teach us whether the change was sound or whether the rejected view deserved to be rejected. Only an impartial analysis of the view in question, an analysis that is not dazzled by the victory or stunned by the defeat of the adherents of the view concerned—could teach us anything regarding the worth of the view and hence regarding the meaning of the historical change.

- Leo Strauss, Natural Right and History (1953), p. 19

- Our understanding of the thought of the past is liable to be the more adequate, the less the historian is convinced of the superiority of his own point of view, or the more he is prepared to admit the possibility that he may have to learn something, not merely about the thinkers of the past, but from them.

- Leo Strauss, What is Political Philosophy?, p. 68

See also

External links

This article is issued from

Wikiquote.

The text is licensed under Creative

Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.